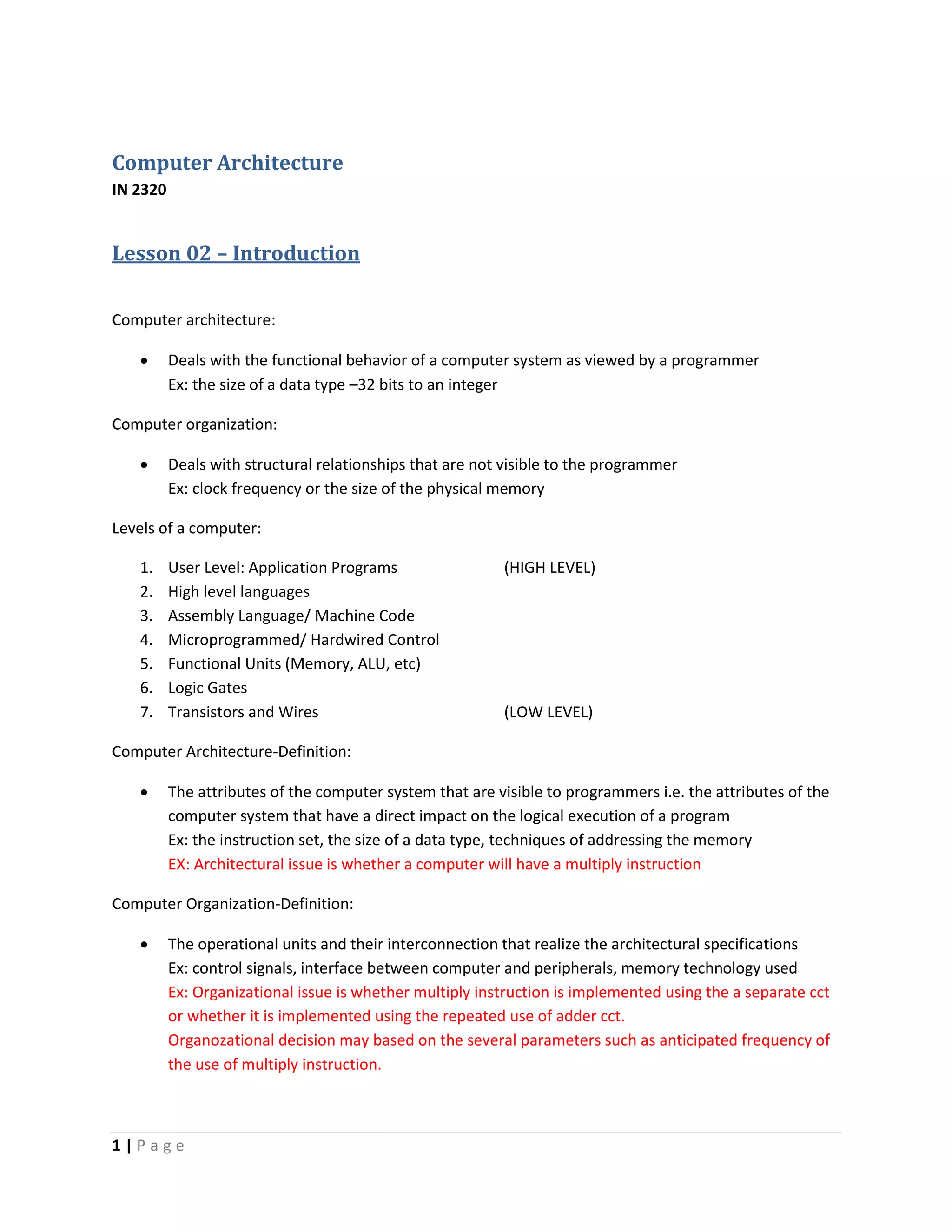

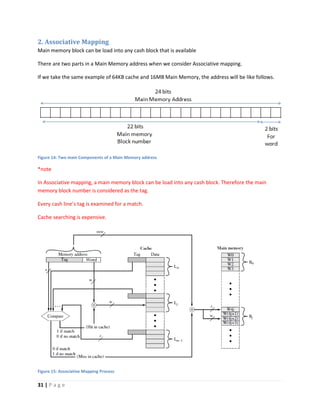

This document discusses computer architecture and organization. It defines computer architecture as the attributes of a computer system that are visible to programmers, such as instruction set and data type sizes, while computer organization refers to the structural relationships not visible to programmers, such as clock frequency. Performance metrics like response time and throughput are also introduced. Architectural choices aim to balance factors like cost, performance, and new technology.