This document provides an illustrated guide to proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) in practice. It is the fourth edition of the guide, which has been fully revised with updated content and full-color illustrations. The guide aims to describe the position of PNF within the current holistic treatment spectrum and provide a practical resource for understanding and applying PNF principles and techniques. It covers PNF procedures, techniques, and patterns as well as their application to patient treatment, with a focus on developing readers' understanding and skills. The authors hope this guide will encourage others to continue advancing the PNF approach to physical therapy.

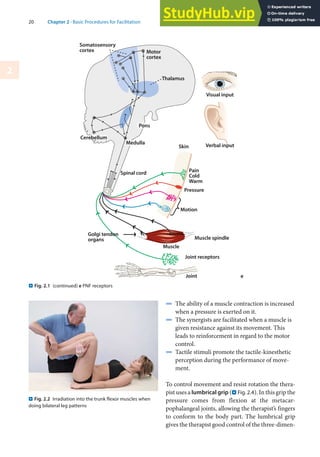

![2

23

2.6 · Visual Stimulus

Definition

The verbal command tells the patient what to

do and when to do it.

The therapist must always bear in mind that the

command is given to the patient, not to the body

part being treated. Preparatory instructions need to

be clear and concise, without unnecessary words.

They may be combined with passive movement and

visual control from the patient to teach the desired

movement.

The timing of the command is important to co-

ordinate the patient’s reactions with the therapist’s

hands and resistance. It guides the start of move-

ment and muscle contractions. It helps give the

patient corrections for motion or stability.

Timing of the command is also very important

when using the stretch reflex. The initial command

should come immediately before the stretch the

muscle chain to coordinate the patient’s conscious

effort with the reflex response (Evarts and Tannji

1974). The action command is repeated to urge

greater effort or redirect the motion.

In reversal techniques, proper timing between

verbal commands and muscle activity is important

when we change the direction of the resistance. A

preparatory command should be given with the

therapist changing hand and an action command

should be given with the therapist applying resis-

tance in the new direction.

The volume with which the command is given

can affect the strength of the resulting muscle con-

tractions (Johansson et al. 1983). The therapist

should give a louder command when a strong

muscle contraction is desired and use a softer and

calmer tone when the goal is relaxation or relief of

pain.

The command is divided into three parts:

1. Preparation: readies the patient for action

2. Action: tells the patient to start the action

3. Correction: tells the patient how to correct and

modify the action.

The repetition, the type of command, as well as the

correction of the movement contribute to the at-

tentiveness of the patient. Furthermore, the patient

is inspired to exert more effort or correct his move-

ment. For example, the command for the lower ex-

tremity pattern of flexion–adduction–external rota-

tion with knee flexion might be [preparation]

»ready, and«; [action] »now pull your leg up and in«;

[correction] »keep pulling your toes up« (to correct

lack of dorsiflexion).

Points to Remember

For elderly patients, the visual input can be

more important than the verbal input (Gentile

1987; Lee and Lishman 1975).

2.6 Visual Stimulus

Definition

Visual feedback promotes muscular activity,

by helping with coordination, strength, and

stability.

Therapeutic Goals

4 The therapist receives visual information as to

whether the applied stimulus was appropriate for

the task, or whether it was too intensive or even

caused pain.

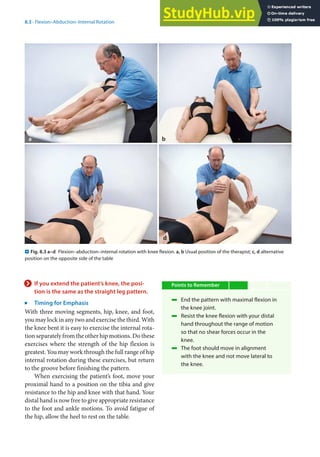

. Fig. 2.6 Positioning of the therapist’s body for the leg

pattern flexion–abduction–internal rotation

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anillustratedguidepnfinpracticefourthedition-230805192459-547ae622/85/An-Illustrated-Guide-PNF-In-Practice-Fourth-Edition-33-320.jpg)

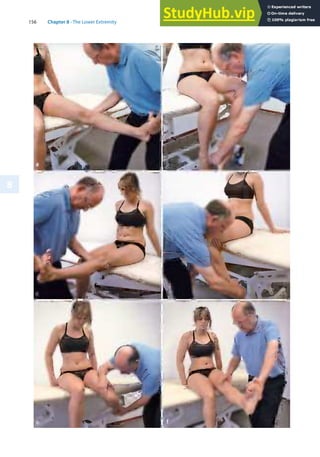

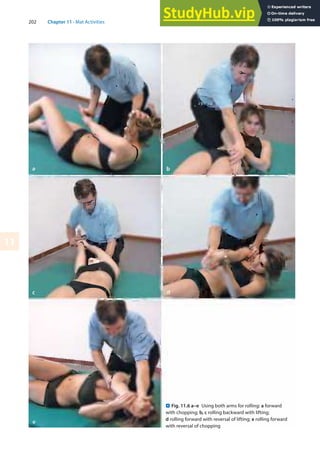

![234 Chapter 11 · Mat Activities

11

j

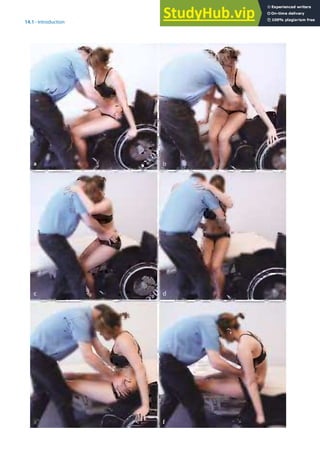

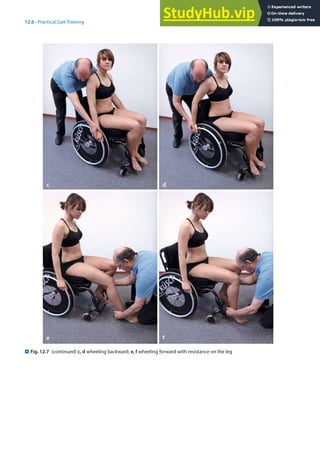

Patient III: Ankylosing spondylitis (Spondylitis ankylopoetica)1 (. Fig. 11.39)

1 Ankylosing spondylitis: The form of rheumatoid arthritis affecting the spine. It occurs predominantly in young males and

produces pain and stiffness as a result of inflammation of the sacroiliac, intervertebral, and costovertebral joints. Aetiology

is unknown. [On-line Medical Dictionary (OMD), Academic Medical Publishing & Cancer WEB 1997–1998].

. Fig. 11.39 a–c Bridging. b Bridging combined with lifting

to the right; c kneeling with lifting

a b

c](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anillustratedguidepnfinpracticefourthedition-230805192459-547ae622/85/An-Illustrated-Guide-PNF-In-Practice-Fourth-Edition-240-320.jpg)

![274 Chapter 12 · Gait Training

12

12.8 Test Your Knowledge: Questions

4 Which muscles are working eccentrically

during the loading response?

4 Why do we use exaggerated exercises in our

PNF gait training?

4 Give five examples of how to use different PNF

techniques in gait or in mat activities.

Further Reading

k

Posture Control and Movement

Finley FR, Cody KA (1969) Locomotive characteristics of

urban pedestrians. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 51:423–426

Gahery Y, Massion J (1981) Co-ordination between posture

and movement. Trends Neurosci 4:199–202

Nashner LM (1980) Balance adjustments of humans per-

turbed while walking. J Neurophysiol 44:650–664

Nashner LM (1982) Adaptation of human movement to

altered environments. Trends Neurosci 5:358–361

Nashner LM, Woollacott M (1979) The organization of rapid

postural adjustments of standing humans: an experi-

mental-conceptual model. In: Talbott RE, Humphrey DR

(eds) Posture and movement. Raven, New York

Woollacott MH, Shumway-Cook A (1990) Changes in posture

control across the life span – a systems approach. Phys

Ther 70:799–807

k

Gait

Göz-Neumann K (2003) Gehen verstehen, Ganganalyse in der

physiotherapie. Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart

Horst R (2005) Motorisches Strategietraining und PNF.

Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart

Inman VT, Ralston HJ, Todd F (1981) Human walking. Williams

and Wilkins, Baltimore

Kettelkamp DB, Johnson RJ, Schmidt GL, et al (1970) An elec-

trogoniometric study of knee motion in normal gait.

J Bone Joint Surg [A] 52:775–790

Lehmann JF (1990) Gait analysis, diagnosis and manage-

ment. In: Krusens handbook of physical medicine and

rehabilitation, Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 108–125

Lehmann JF (1990) Lower extremity orthotics. In: Krusens

Handbook of physical medicine and rehabilitation.

Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 602–646

Mann RA, Hagy JL, White V, Liddell D (1979) The initiation of

gait. J Bone Joint Surg [A] 61:232–239

McFadyen BJ, Winter DA (1988) An integrated biomechanical

analysis of normal stair ascent and descent. J Biomech

21:733–744

Murray MP, Kory RC, Sepic SB (1970) Walking patterns of

normal women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 51:637–650

Murray MP, Drought AB, Kory RC (1964) Walking patterns of

normal men. J Bone Joint Surg [A] 46:335–360

Nashner LM (1976) Adapting reflexes controlling the human

posture. Exp Brain Res 26:59–72

Pohl M, Mehrholz J, Ritschel C, Rückriem S (2002) Speed de-

pendent treadmill training in ambulatory hemiparetic

stroke patients: A RCT. Stroke (33): 553–558

Smidt G (1990) Gait in rehabilitation. Churchill Livingstone,

New York

Sutherland DH (1966) An electromyographic study of the

plantar flexors of the ankle in normal walking on the

level. J Bone Joint Surg [A] 48:66–71

Sutherland DH, Cooper L, Daniel D (1980) The role of the an-

kle plantar flexors in normal walking. J Bone Joint Surg

[A] 62:354–363

Sutherland DH, Olshen R, Cooper L, Woo SLY (1980) The de-

velopment of mature gait. J Bone Joint Surg 62:336–353

Wang RY (1994) The effect of proprioceptive neuromuscular

facilitation in case of patients with hemiplegia of long

and short duration. Phys Ther 1994 (12): 25–32

Winter D (1989) The biomechanics and motor control of

human gait. University of Waterloo Press, Waterloo

Wittle M (1991) Gait analysis: an introduction. Butterworth-

Heinemann, Oxford

Yigiter K, Sener G, Erbahceci F, BayarK, Ülger ÖG, Akodogan S

(2002) A comparison of traditional prosthetic training

versus PNF resistive gait training with trans-femoral am-

putees. Prosthet Orthot Int (26): 213–217

References

Adler SS (1976) Influence of »Joint Approximation« on lower

extremity extensor muscles: an EMG study. Unpublished

thesis presented at APTA annual conference, New Orleans

Beckers D, Deckers J (1997) Ganganalyse und Gangschulung,

Springer Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg New York

Eberhart HD, Inman VT, Bresler B (1954) The principal elements

in human locomotion. In: Klopteg PE, Wilson PD (eds)

Human limbs and their substitutes. McGraw-Hill, New York

Horak FB, Nashner LM (1986) Central programming of pos-

tural movements: adaptation to altered support-surface

configurations. J Neurophysiol 55 (6):1369–1381

Inman VT, Ralston HJ, Todd F (1981) Human walking. Williams

& Wilkins, Baltimore

Lerner-Frankiel MB, Vargas S, Brown M, Krusell L (1986) Func-

tional community ambulation: what are your criteria?

Clin Management 6 (2):12–15

Murray MP, Drought AB, Kory RC (1964) Walking patterns of

normal men. J Bone Joint Surg [A]:335–360

Nuzik S, Lamb R, VanSant A, Hirt S (1986) Sit-to-stand move-

ment pattern, a kinematic study. Phys Ther 66 (11):

1708–1713

Perry J (1992) Gait analysis, normal and pathological func-

tion. Slack, NJ

Podsiadlo D et al (1991) The timed »Up and go«: a test of basic

functional mobility for elderly persons. American Geriat-

rics Society 39:142–148](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anillustratedguidepnfinpracticefourthedition-230805192459-547ae622/85/An-Illustrated-Guide-PNF-In-Practice-Fourth-Edition-280-320.jpg)