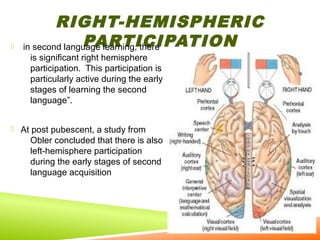

This document discusses factors that influence age and acquisition of language. It presents the critical period hypothesis, which suggests a biological timeframe for acquiring a first language most easily, typically before puberty. While second languages can still be learned later, acquisition beyond puberty involves greater participation of the right hemisphere of the brain. Adults also face challenges like foreign accent and interference between the first and second languages, though their cognitive abilities allow for some rote learning. The development of one's language ego during puberty can make learning a new language more difficult.