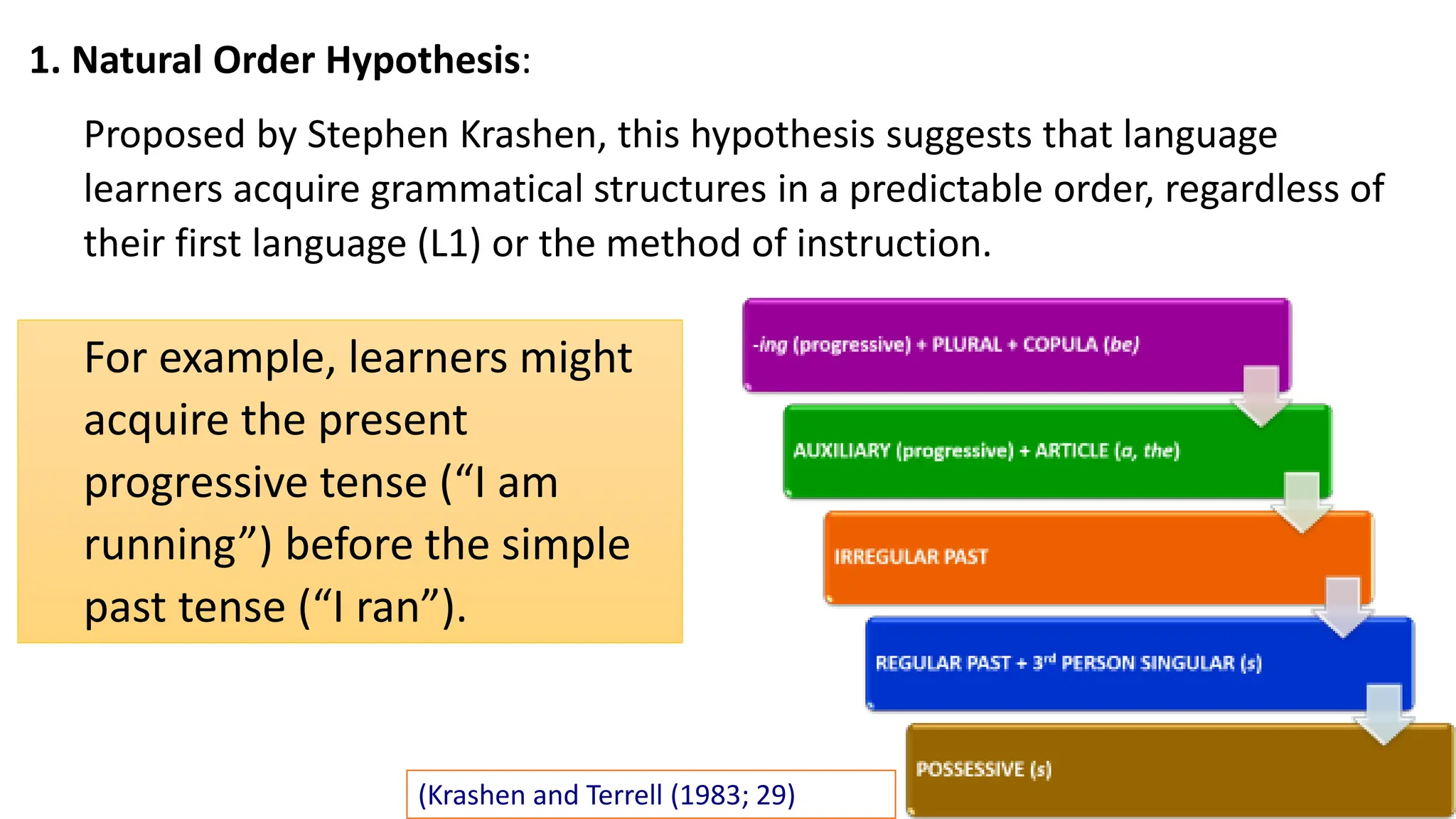

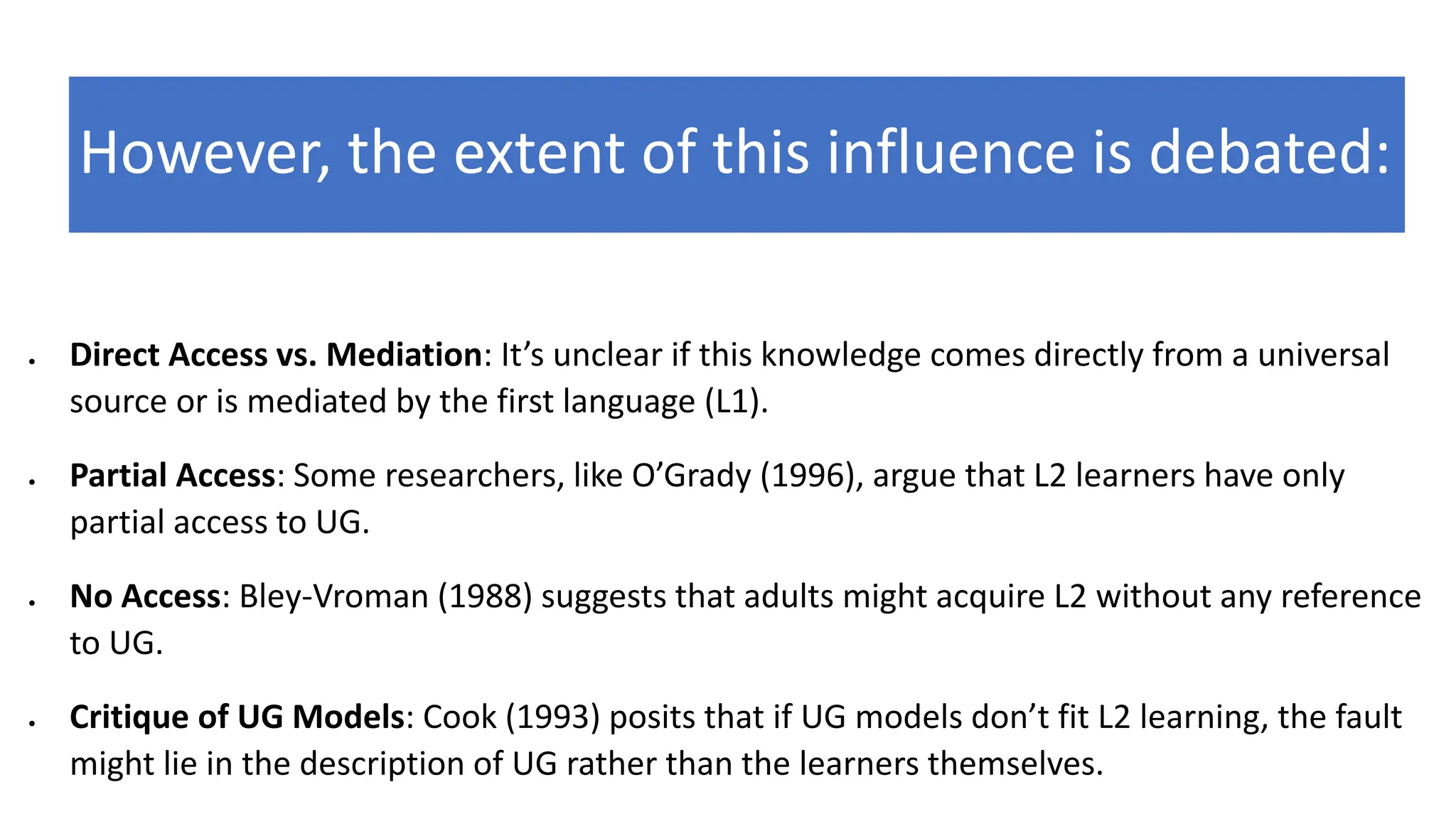

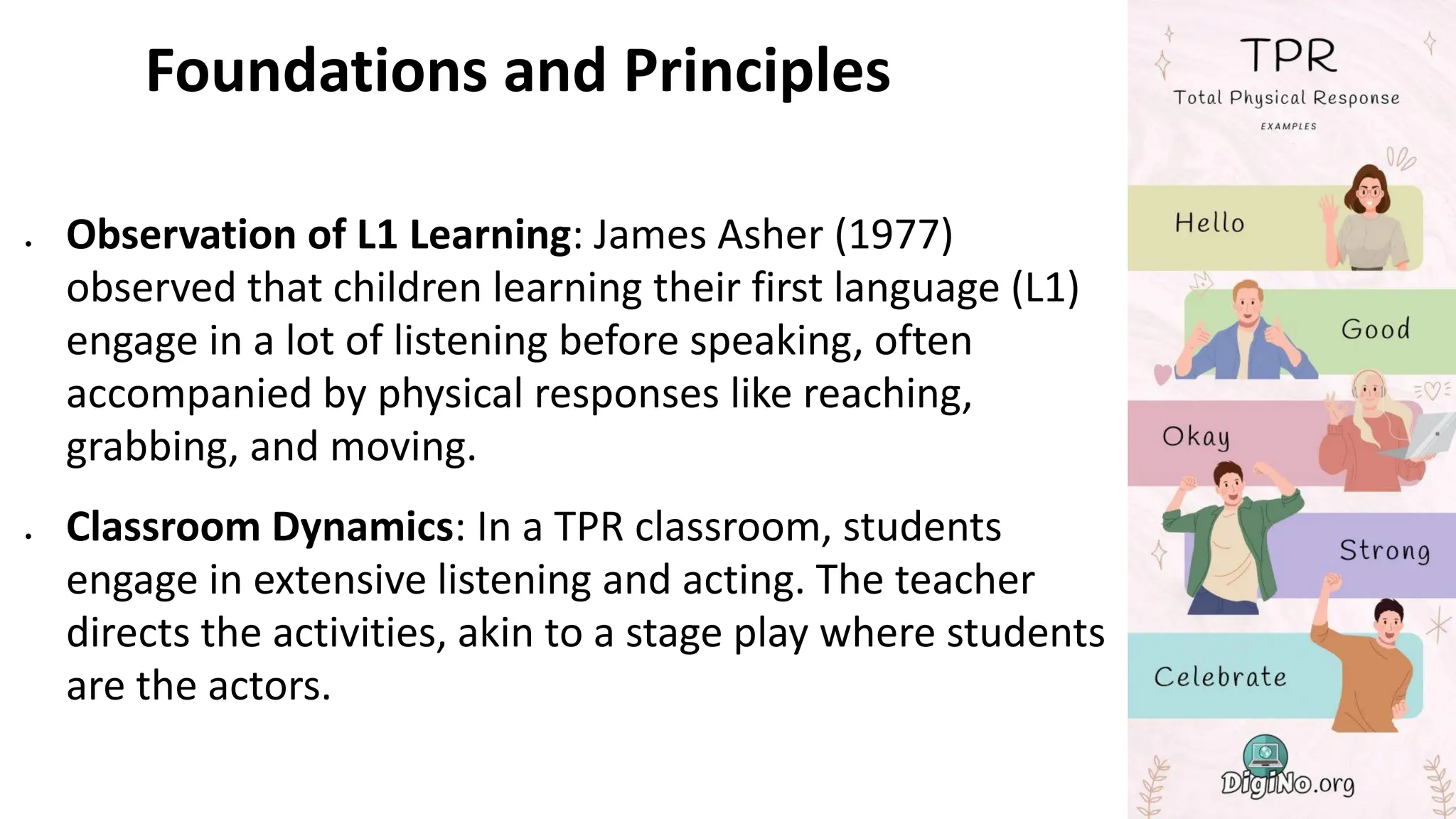

The document discusses age and its impact on second language acquisition (SLA), highlighting that children often learn languages more easily than adults due to factors such as brain plasticity and learning environments. It addresses common myths about SLA, critiques inappropriate comparisons between child and adult language acquisition, and outlines the natural order of language learning as proposed by Stephen Krashen. Furthermore, it introduces concepts like the Critical Period Hypothesis, various learning strategies, and classroom methodologies that emphasize a natural approach to language learning.