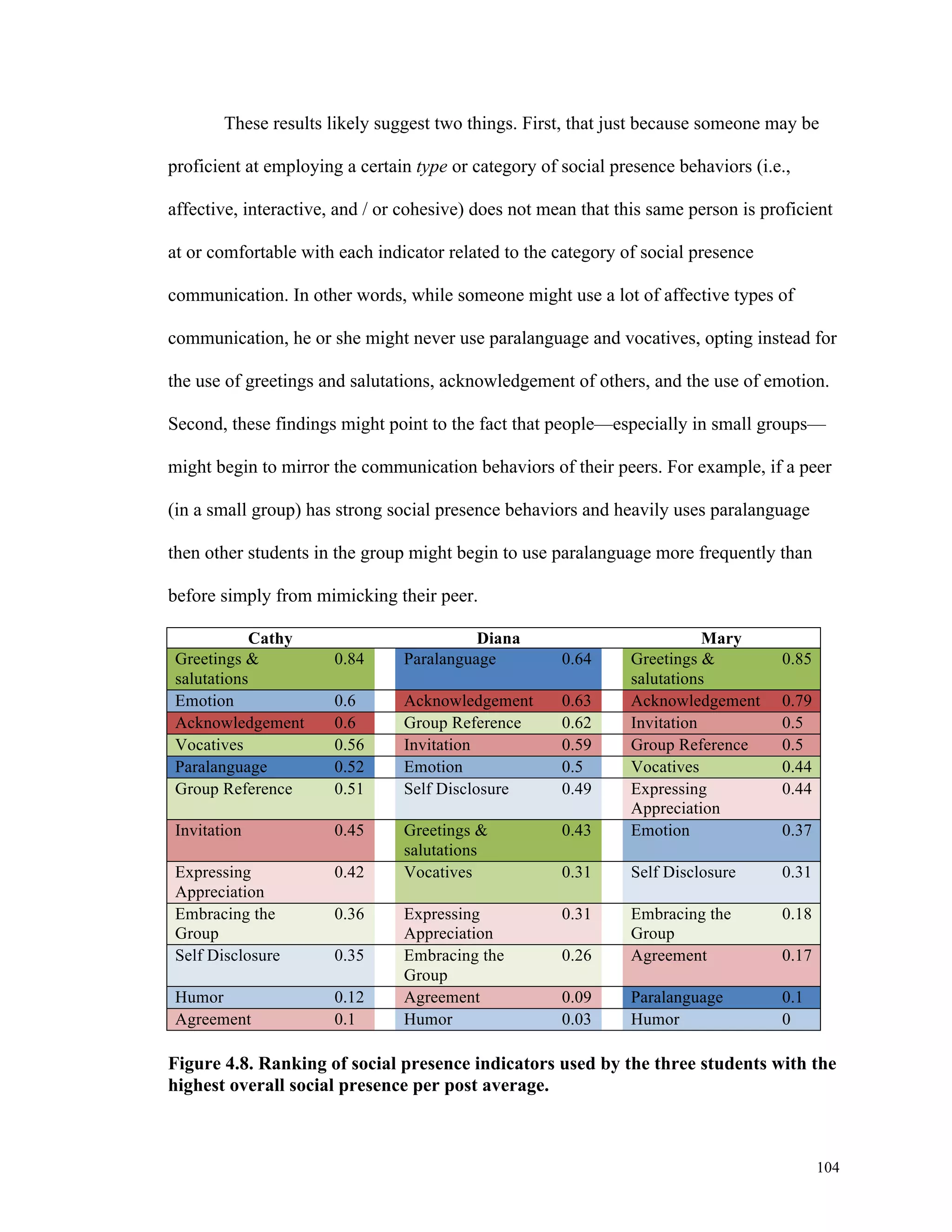

The thesis by Patrick Ryan Lowenthal explores the concept of social presence in online learning, examining how it manifests in fully asynchronous courses. It critiques previous research for primarily focusing on student perceptions rather than the establishment of social presence, employing a mixed-methods approach to analyze communication in online discussions. The study finds that social presence is influenced by various situational factors such as group size and instructional tasks, suggesting complexities in fostering social presence in online education.

![16

Sample

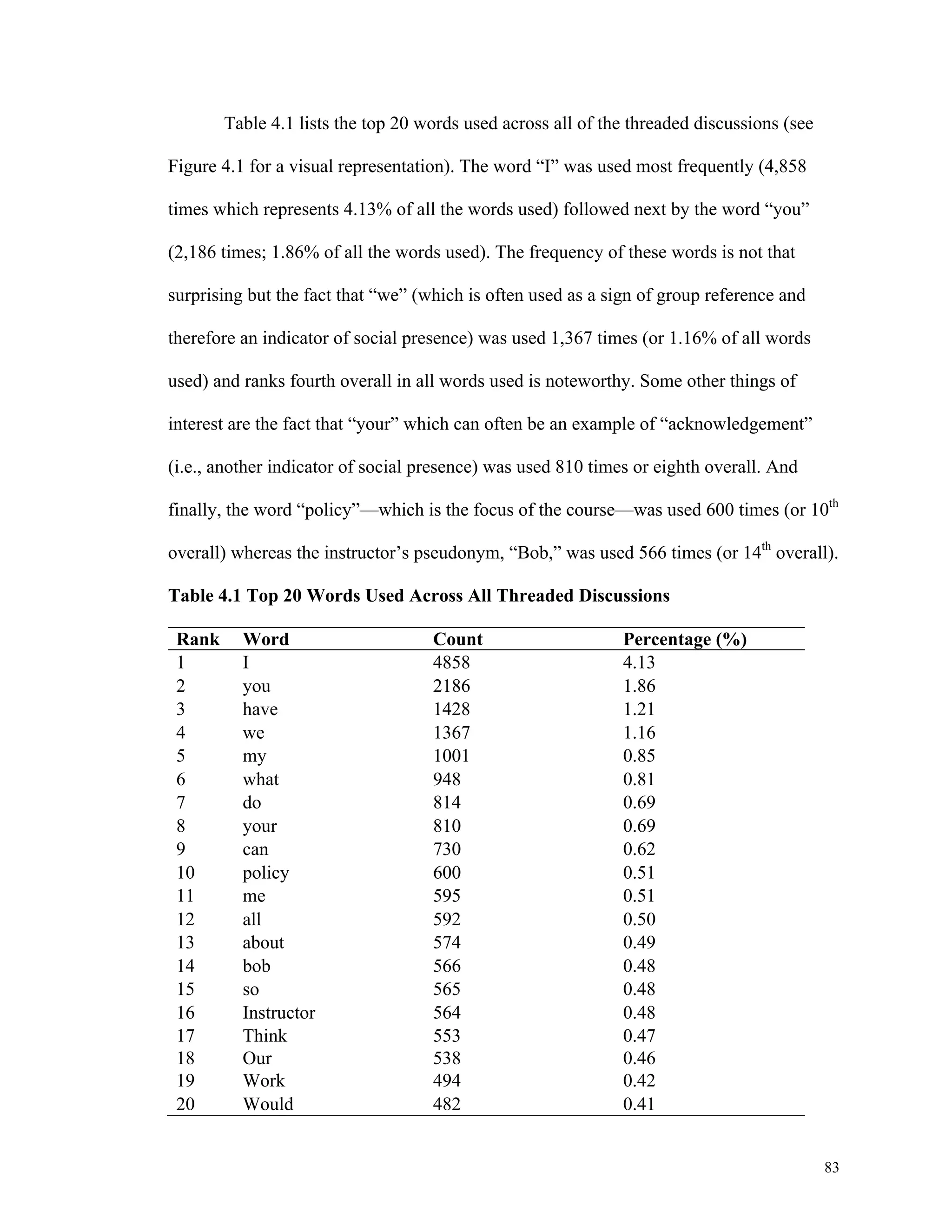

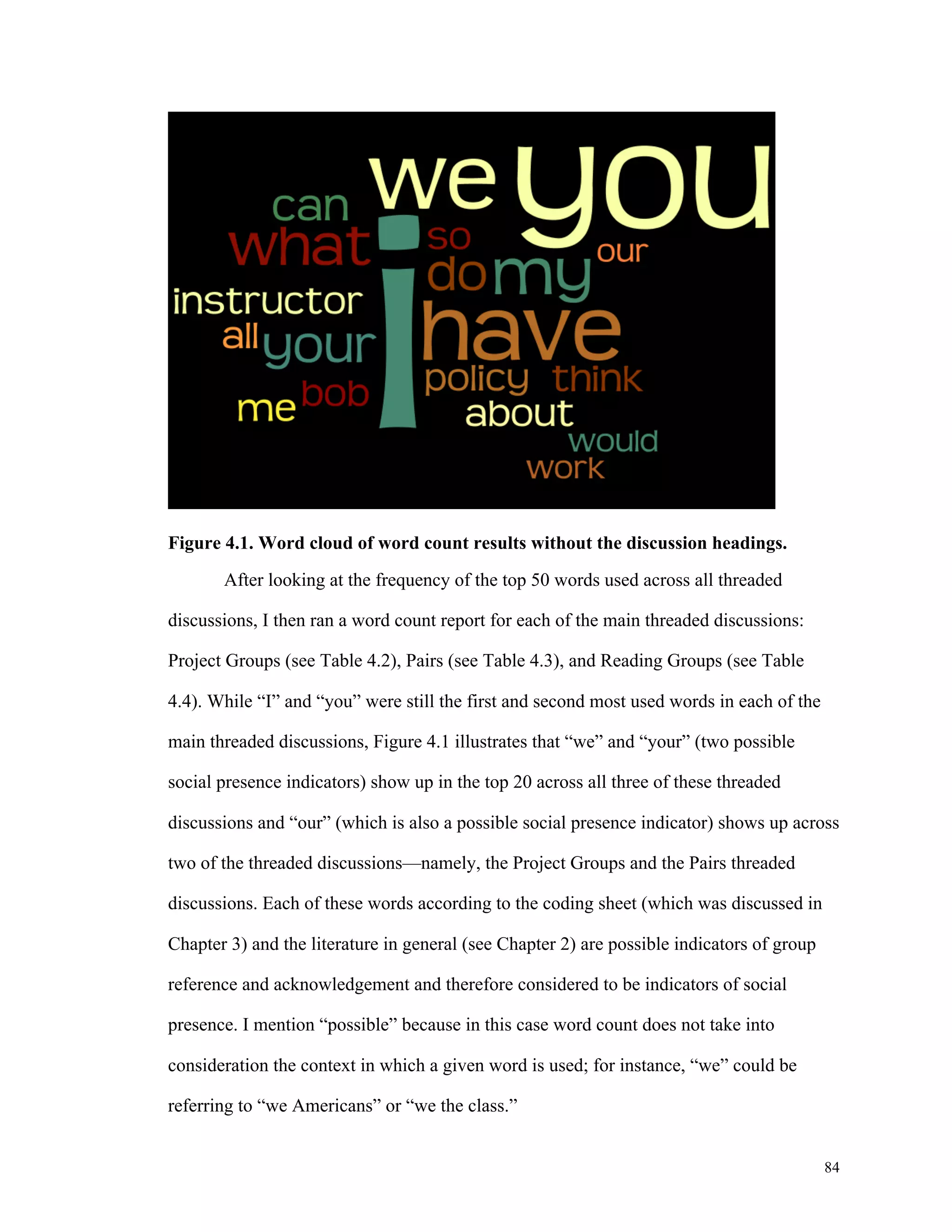

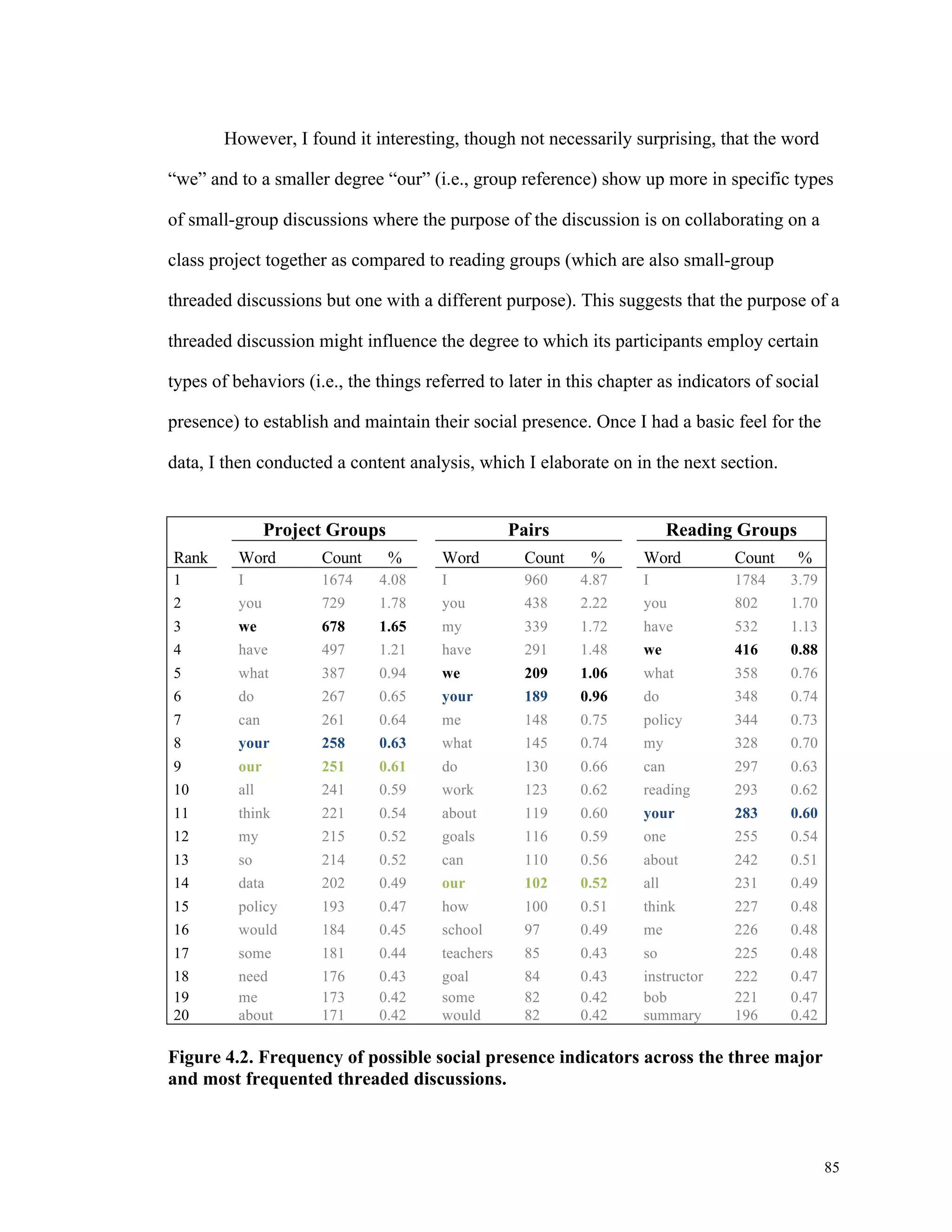

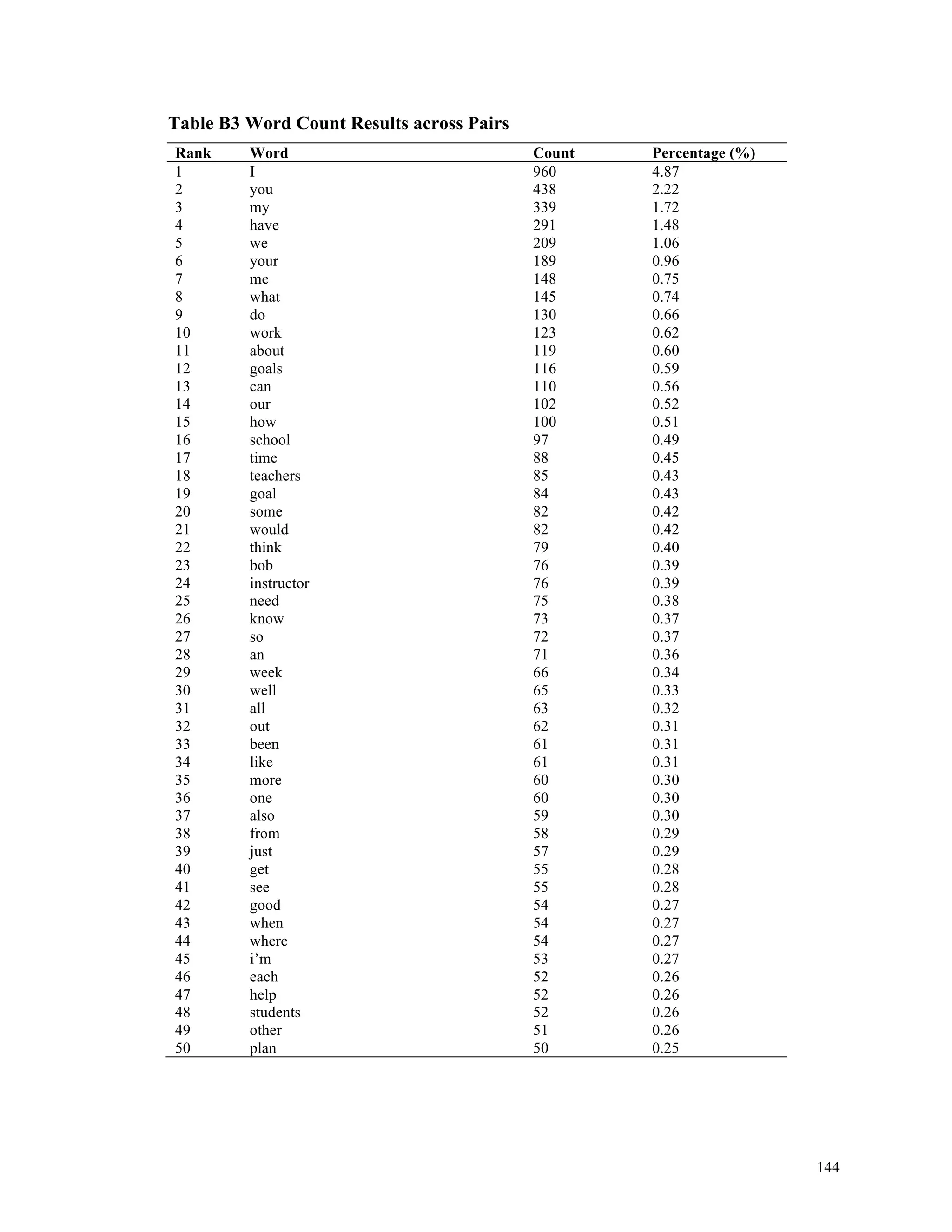

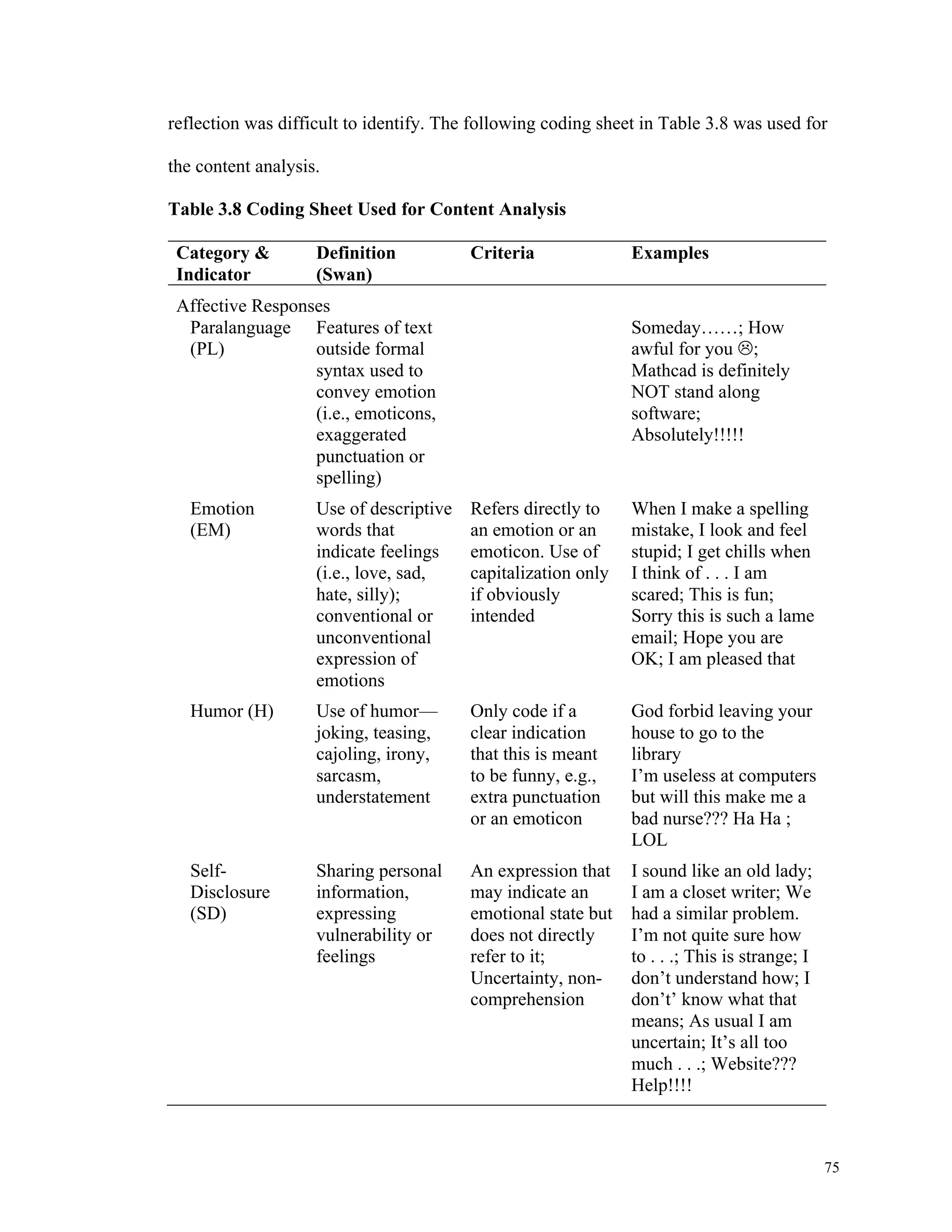

A single, completely online graduate course in education was purposefully and

conveniently sampled for this study. Thus, a non-random (non-probability) criterion

sampling scheme was used in this study (Onwuegbuzie & Collins, 2007). A section of

EDLI 7210 Educational Policy Making in a Democratic Society—which was taught

online in the spring of 2007—was identified as an appropriate sample for this study. The

course was a graduate-level online course in the School of Education and Human

Development at the University of Colorado Denver delivered via eCollege. All of the

threaded discussions in the eCollege course shell for this course were used for this study.

The population of the course primarily consisted of graduate students completing

coursework for an Educational Specialist (EdS) degree or a PhD. Many of the EdS

students were also seeking their principal license. Nineteen graduate students were

enrolled in the course.

Data Analysis

The majority of research on social presence has relied primarily on self-report

survey data (e.g., Gunawardena, 1995; Richardson & Swan, 2003). While self-report

survey measures are useful and have their place in educational research, as Kramer, Oh,

and Fussell (2006) point out, they “are retroactive and insensitive to changes in presence

over the course of an interaction [or semester]” (p. 1). In this study, rather than focus on

students’ perceptions of presence (which I have done in other studies such as Lowenthal

& Dunlap, 2011; Lowenthal, Lowenthal, & White, 2009), I focused instead on what was

“said” in the online threaded discussions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3506428-libre-141017143206-conversion-gate01/75/SOCIAL-PRESENCE-WHAT-IS-IT-HOW-DO-WE-MEASURE-IT-31-2048.jpg)

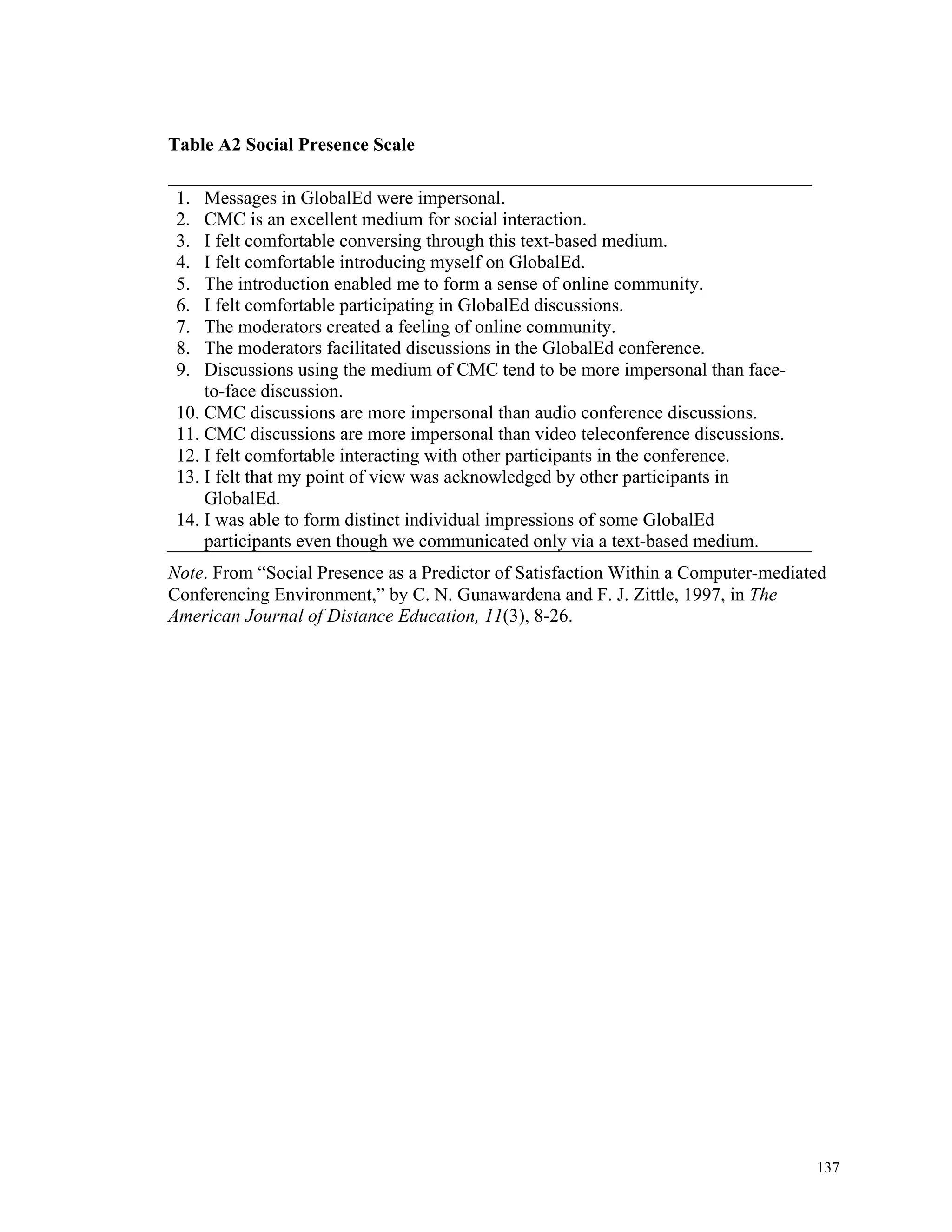

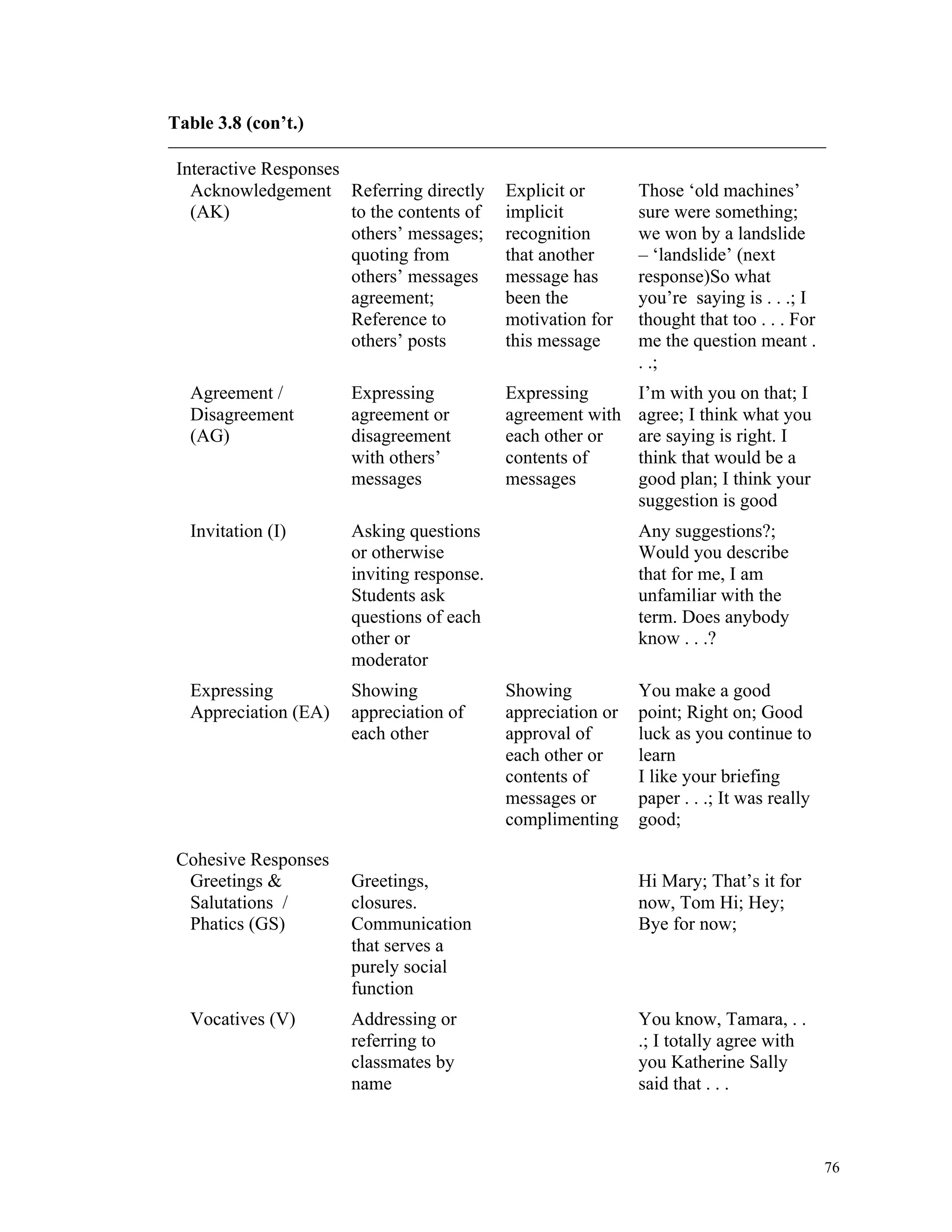

![online privacy as a dimension of social presence in later studies (Tu & Corry, 2004; Tu &

38

McIsaac, 2002). Despite the strengths of his survey, Tu and McIsaac (2002) later

determined as the result of a mixed method study, using the SPPQ and a dramaturgy

participant observation qualitative approach, “there were more variables that contribute to

social presence” (p. 140) than previously thought. Therefore, Tu and McIsaac concluded

that social presence was more complicated than past research suggested. Appendix A

outlines the new variables identified by Tu and McIsaac. Specifically, they found that the

social context played a larger role than previously thought.

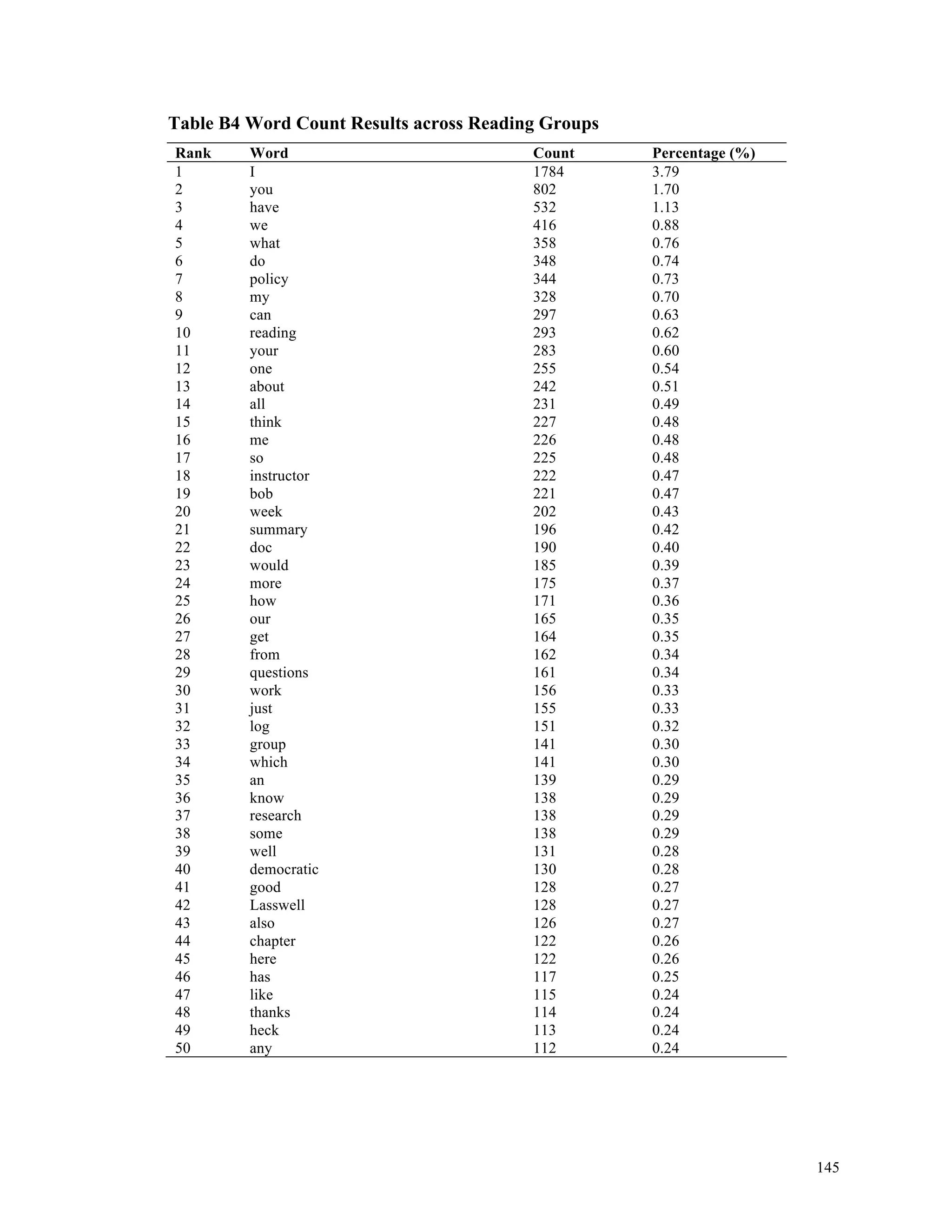

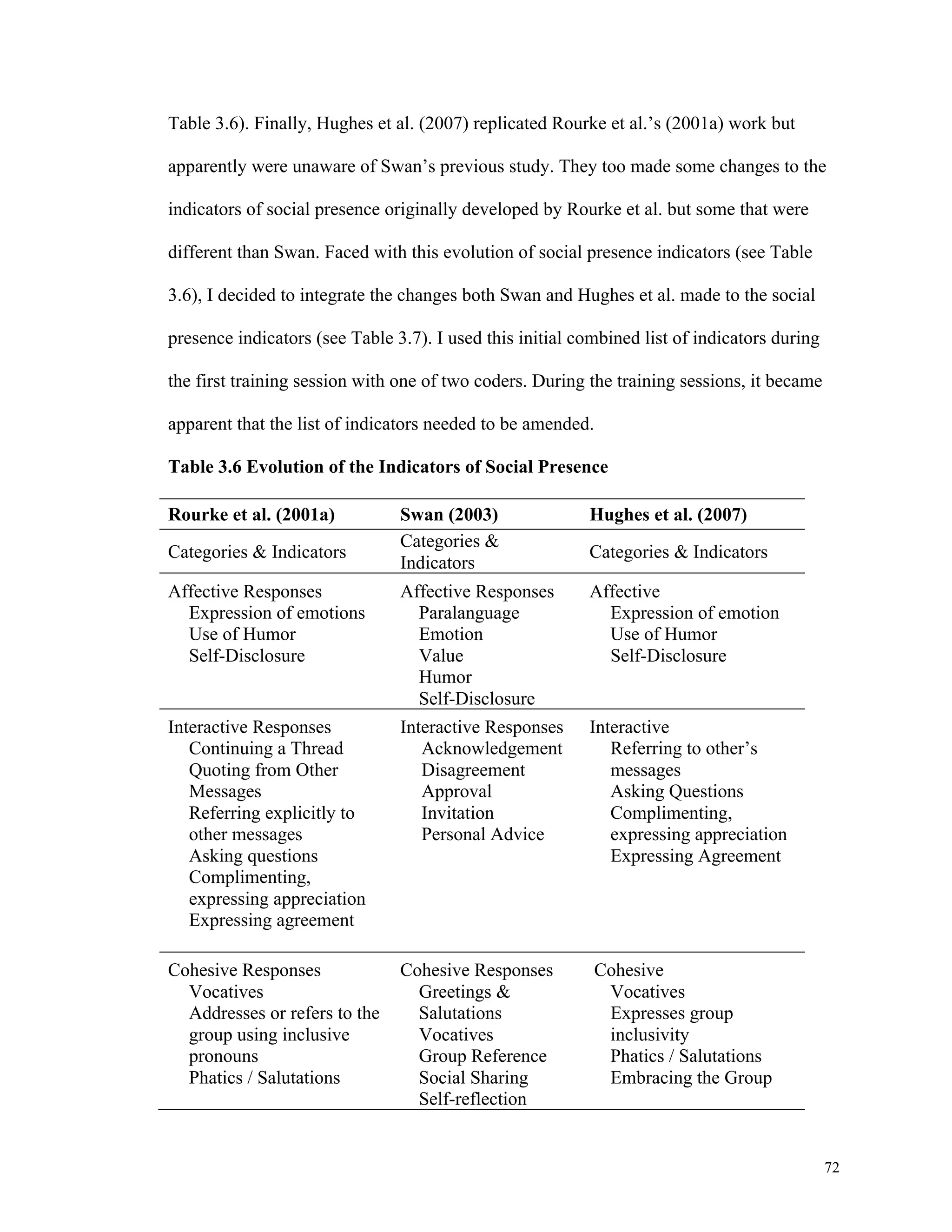

Among other things, the preceding literature illustrates what other researchers

have pointed out—that there is still little agreement on how to measure social presence

(Lin, 2004; Stein & Wanstreet, 2003). Just as Tu criticized how Gunawardena measured

social presence, others have criticized and modified Tu’s work (Henninger &

Viswanathan, 2004). Also, while social presence has been presented as a perceptual

construct, Hostetter and Busch (2006) point out that relying solely on questionnaires (i.e.,

self-report data) can cause problems because “respondents may be providing socially

desirable answers” (p. 9). Further, Kramer, Oh, and Fussell (2006) point out that self-report

data “are retroactive and insensitive to changes in presence over the course of an

interaction [or semester]” (p. 1). But at the same time, even the scale created by Rourke

et al. (2001a) has been modified by Swan (2003) and later by Hughes, Ventura, and

Dando (2007) for use in their own research.

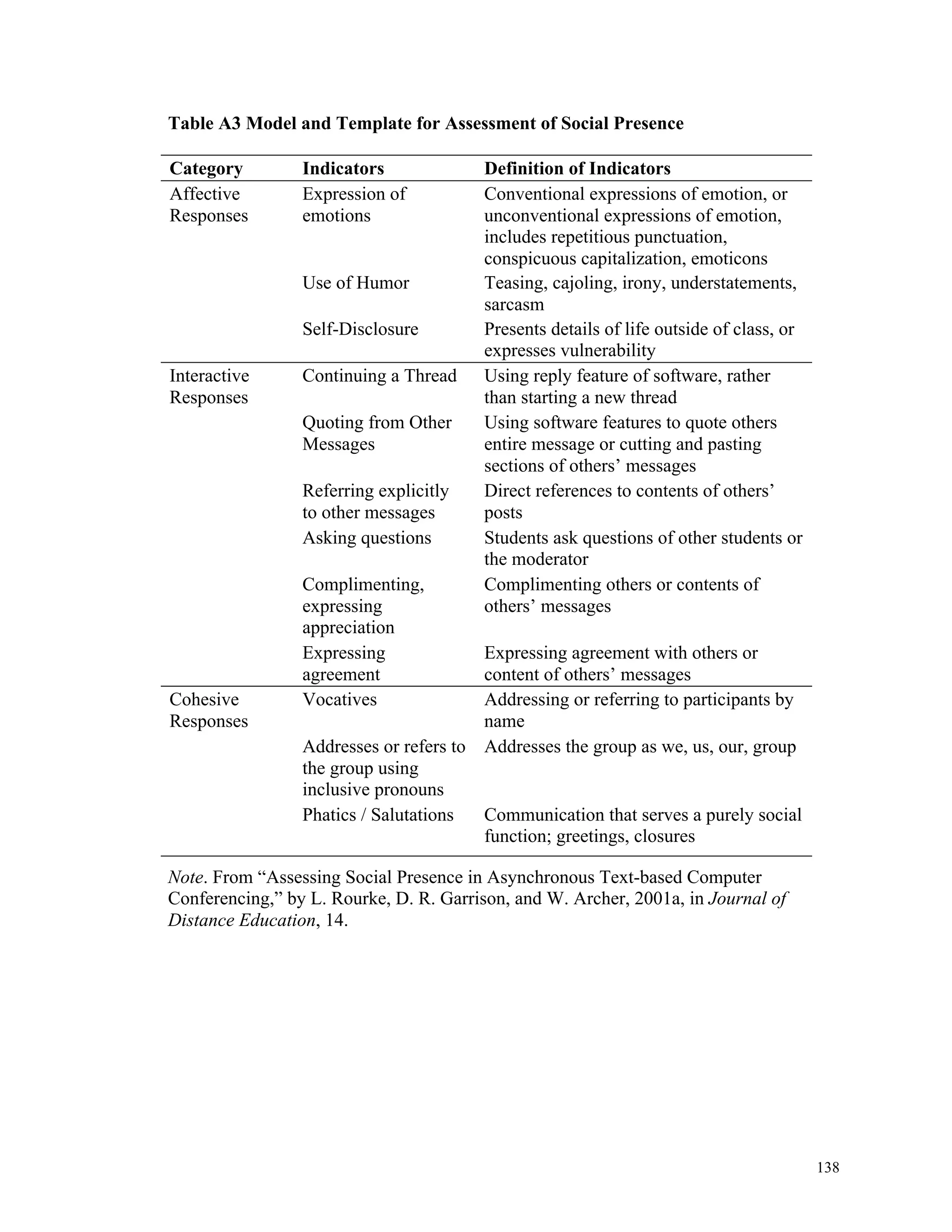

During the past few years, researchers have focused less on studying social

presence by itself—opting instead to study social presence as one aspect of a CoI. As a

result and likely due to the difficulty of coding large samples, these researchers have](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3506428-libre-141017143206-conversion-gate01/75/SOCIAL-PRESENCE-WHAT-IS-IT-HOW-DO-WE-MEASURE-IT-53-2048.jpg)

![46

concluded that it is not the quantity but the quality of interactions online that make the

difference.

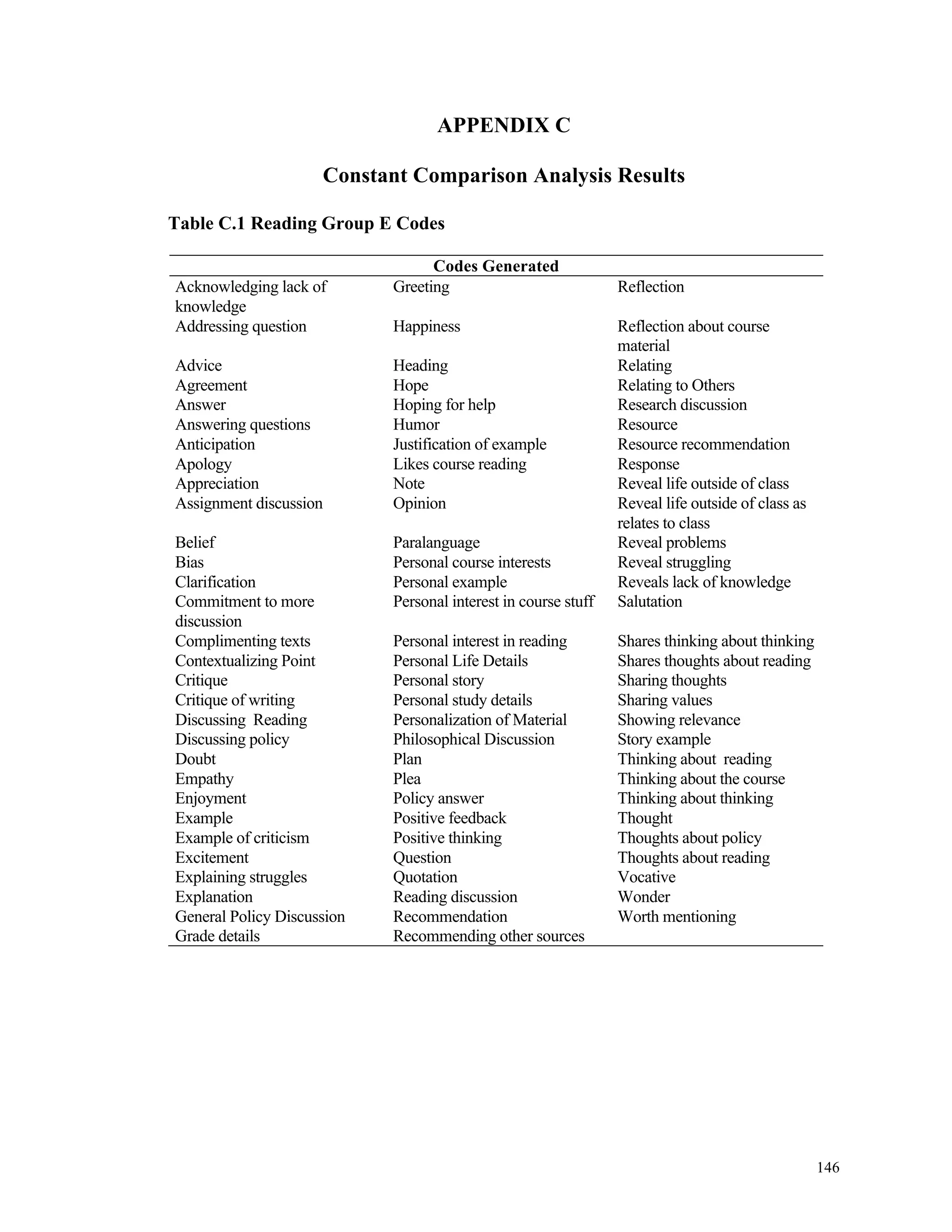

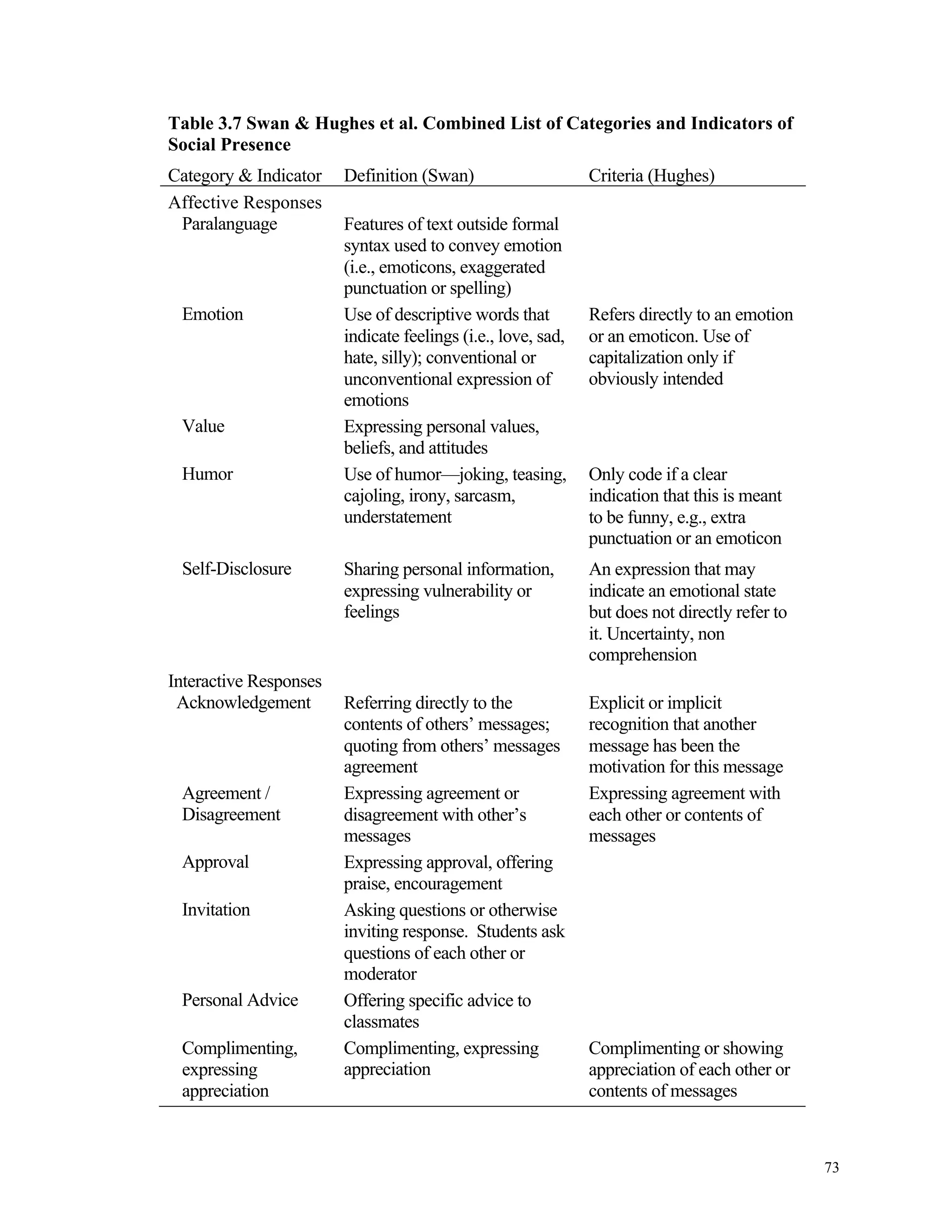

Like Tu and McIsaac, Swan and Shih (2005) also discovered some interesting

relationships between social presence and interaction. The participants in their study

came from four online graduate educational technology courses; 51 students completed

an online questionnaire [based on Richardson and Swan’s (2003) previous survey that

was based on the instrument developed by Gunawardena and Zittle]. After the survey was

completed, the 5 students with the highest and the 5 students with the lowest social

presence scores were identified, their postings were analyzed, and then they were

interviewed. Content analysis was used to explore the discussion postings using the

indicators developed by Rourke et al. (2001a).

Like Tu and McIsaac (2002), Swan and Shih found that students who interacted

more in the discussion forums were not necessarily perceived as having the most social

presence; rather, students who were more socially orientated, even if they interacted less

than others, were perceived as having greater social presence. Swan and Shih argued that

this supports the idea that perceived presence is not directly linked to how much one

participates online. Further, they found that students perceiving the most social presence

of others were also the ones who successfully projected their own presence into the

discussions. Swan and Shih concluded that students projected their presence online “by

sharing something of themselves with their classmates, by viewing their class as a

community, and by acknowledging and building on the responses of others” (p. 124),

rather than simply posting more than others. Therefore, this research suggests that the

quality of online postings matters more than the quantity when it comes to social](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3506428-libre-141017143206-conversion-gate01/75/SOCIAL-PRESENCE-WHAT-IS-IT-HOW-DO-WE-MEASURE-IT-61-2048.jpg)

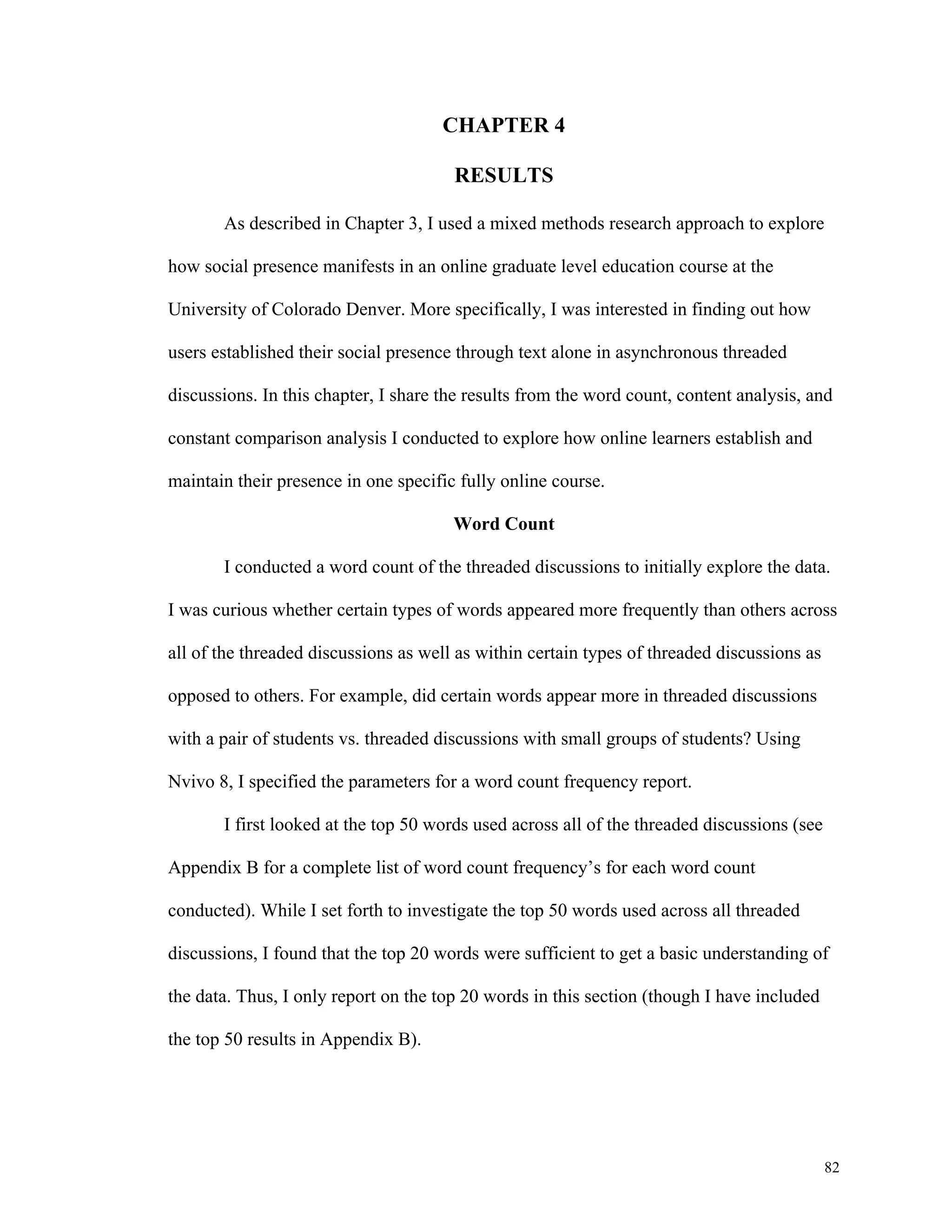

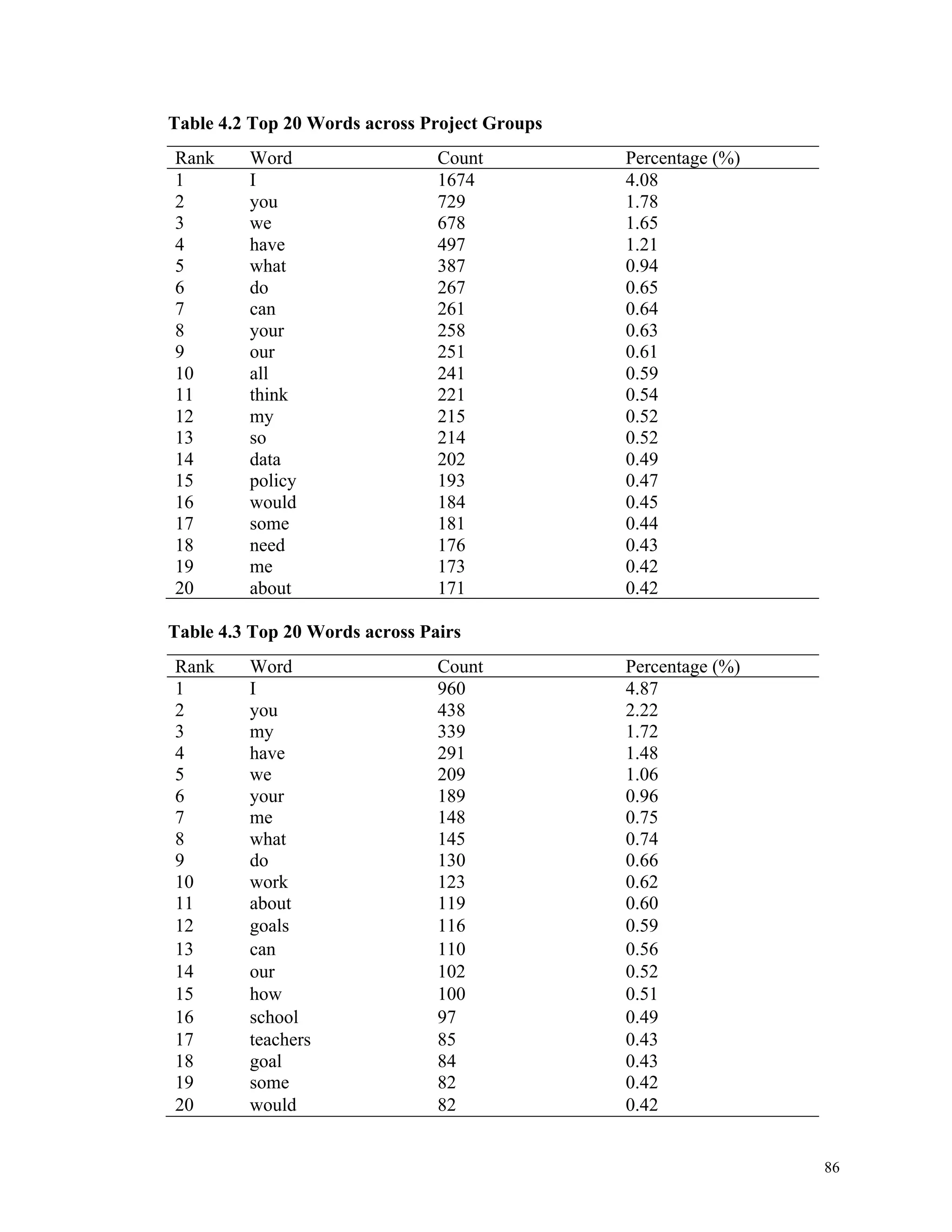

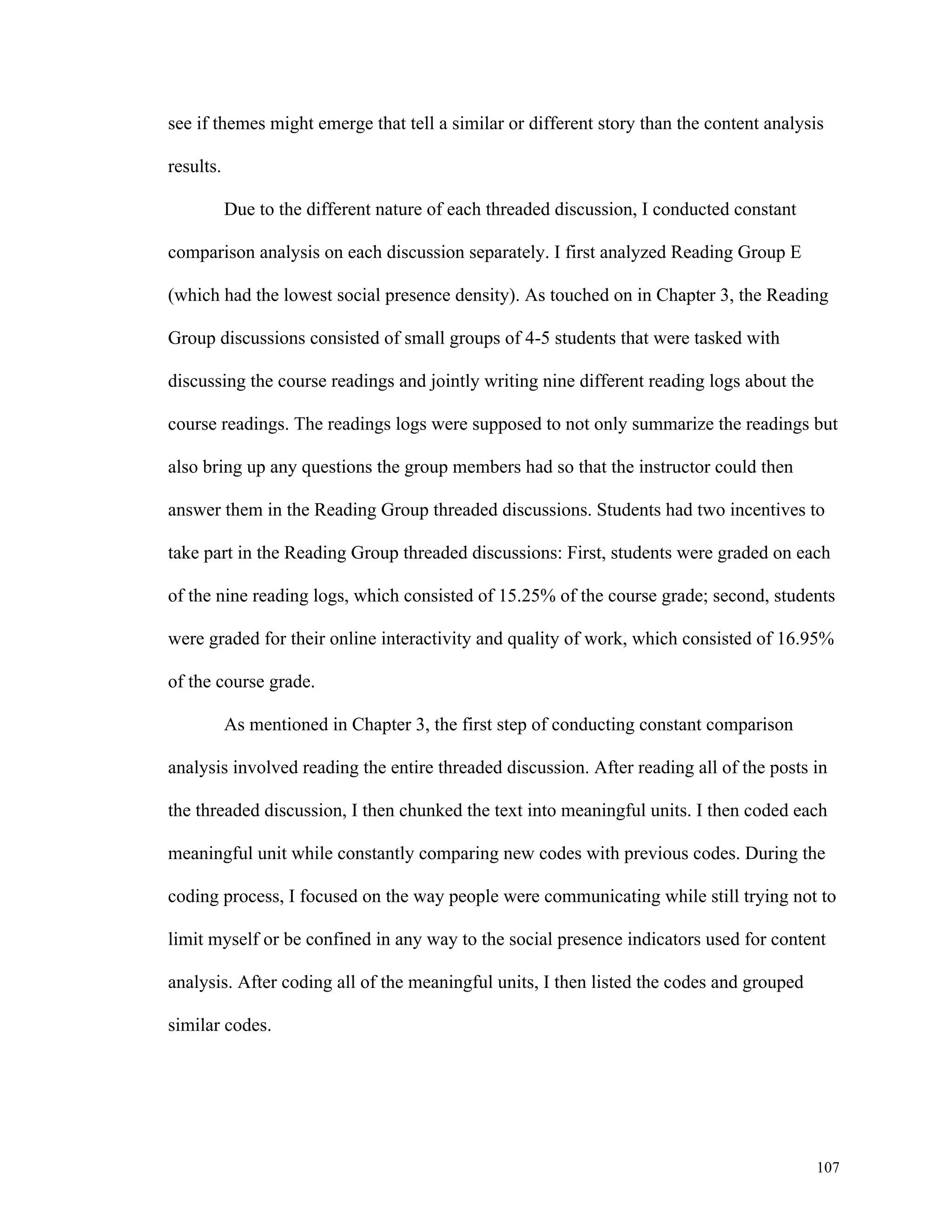

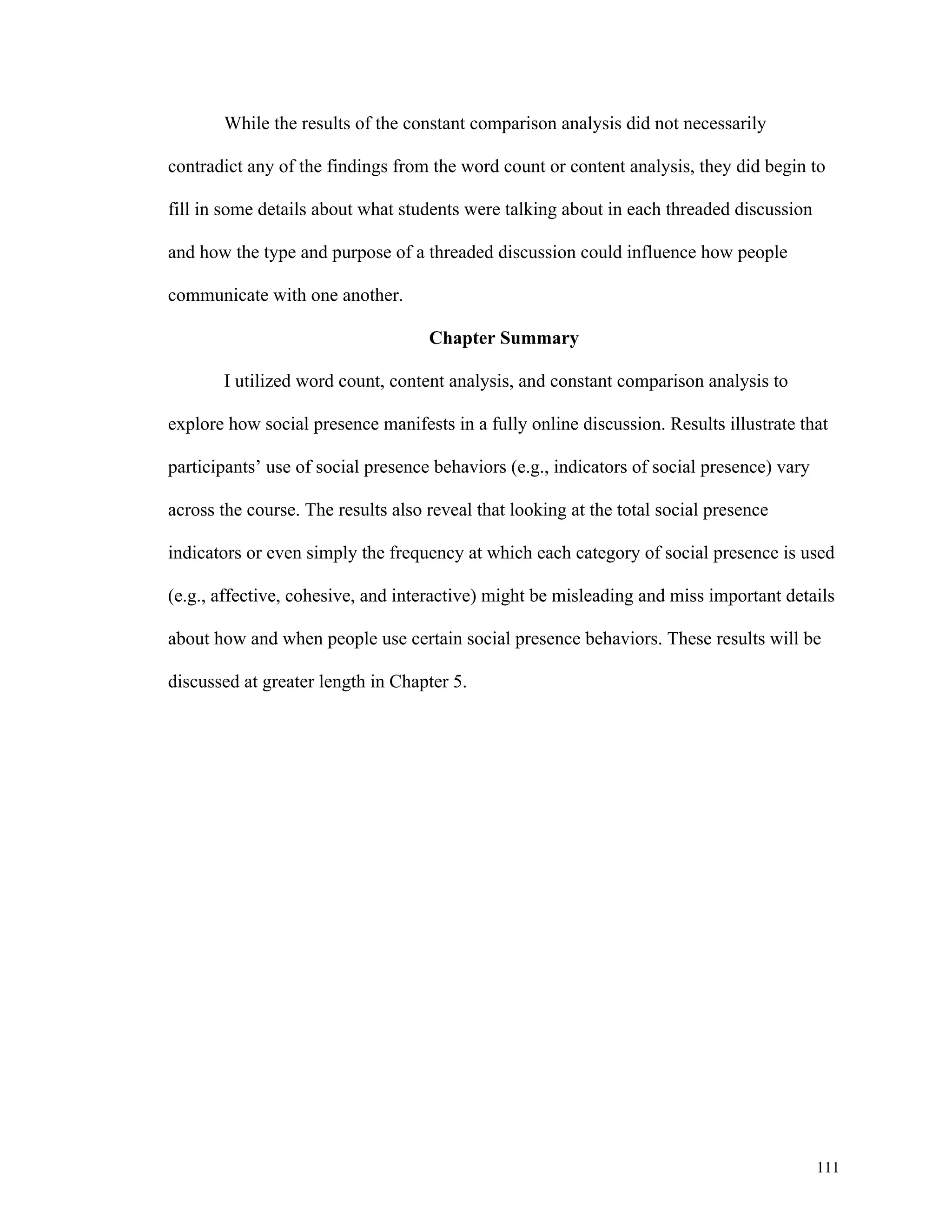

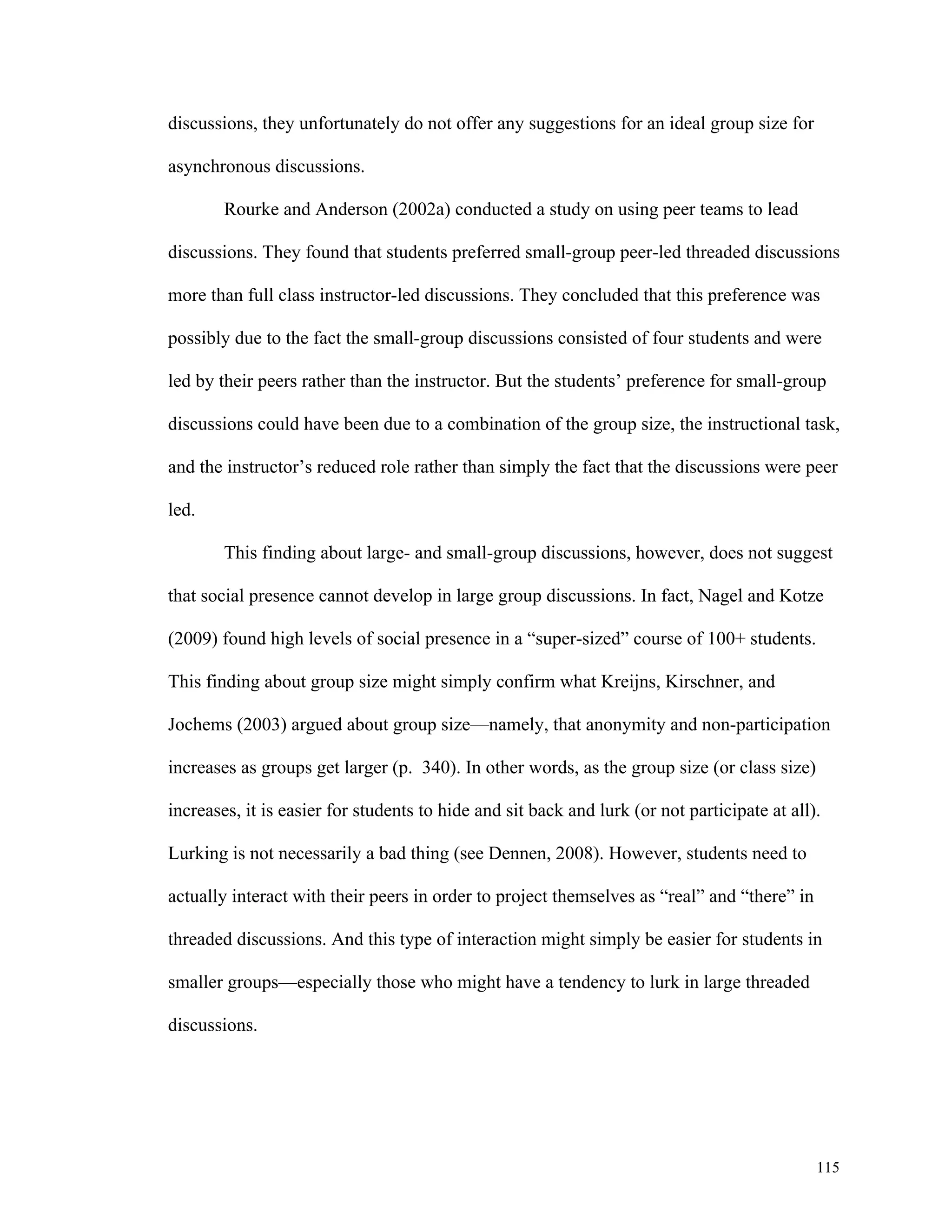

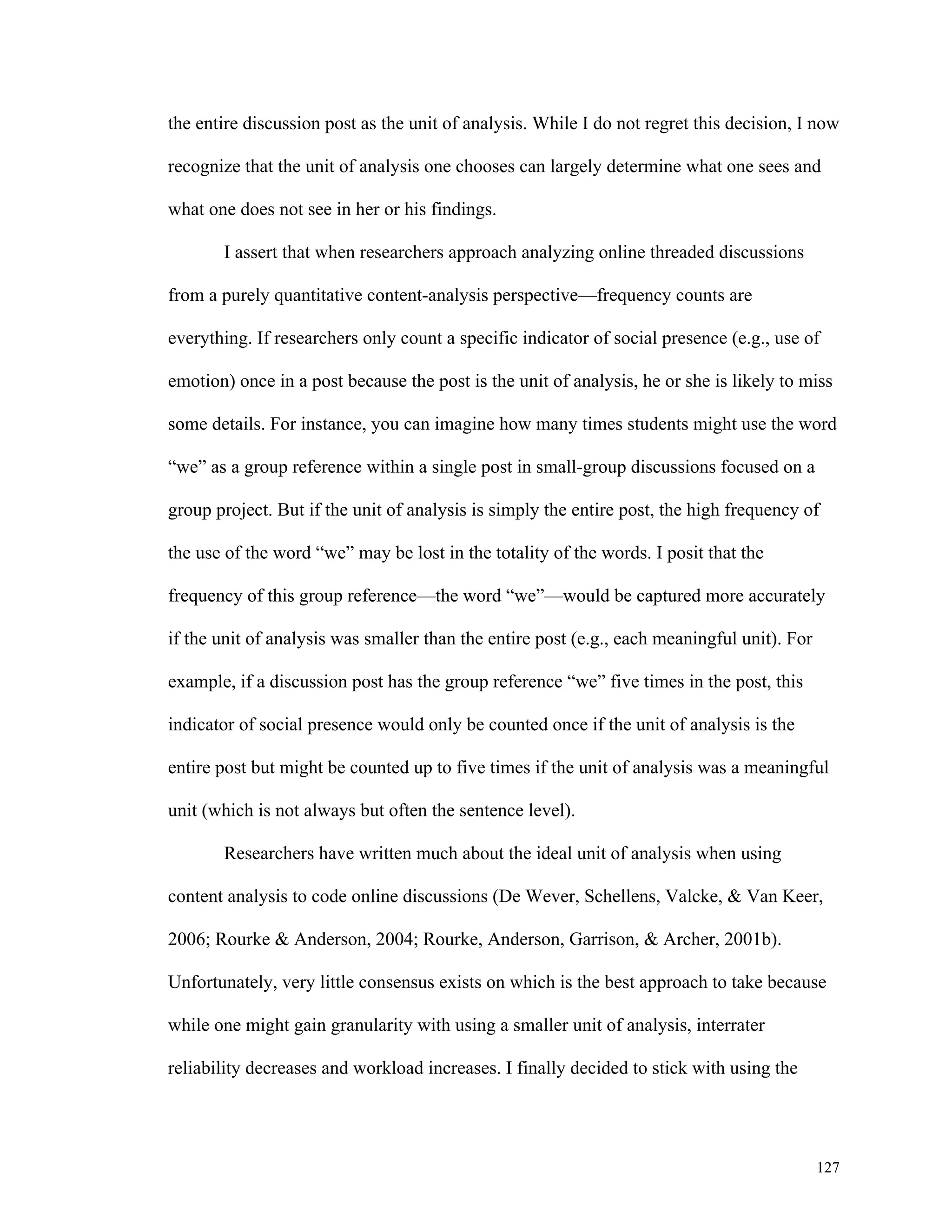

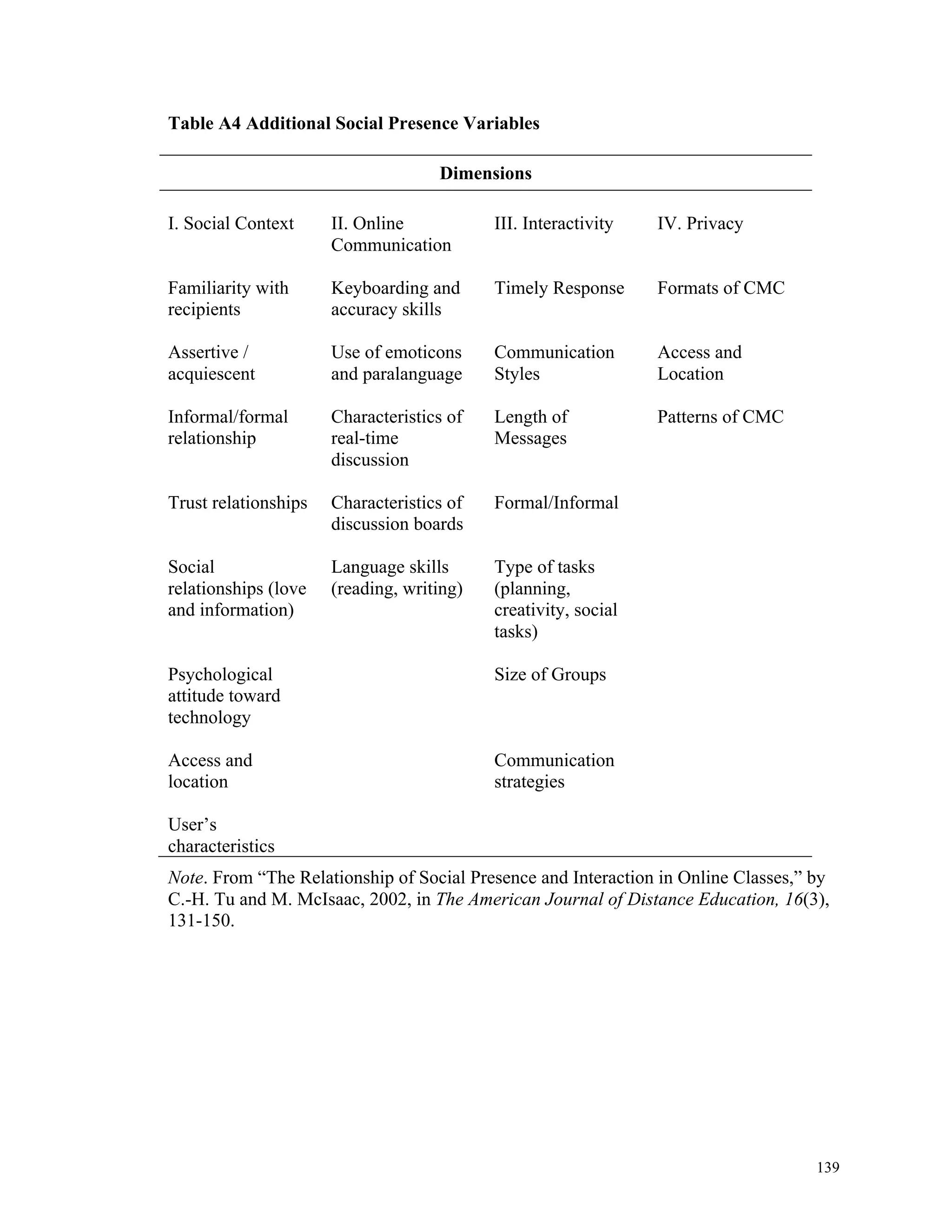

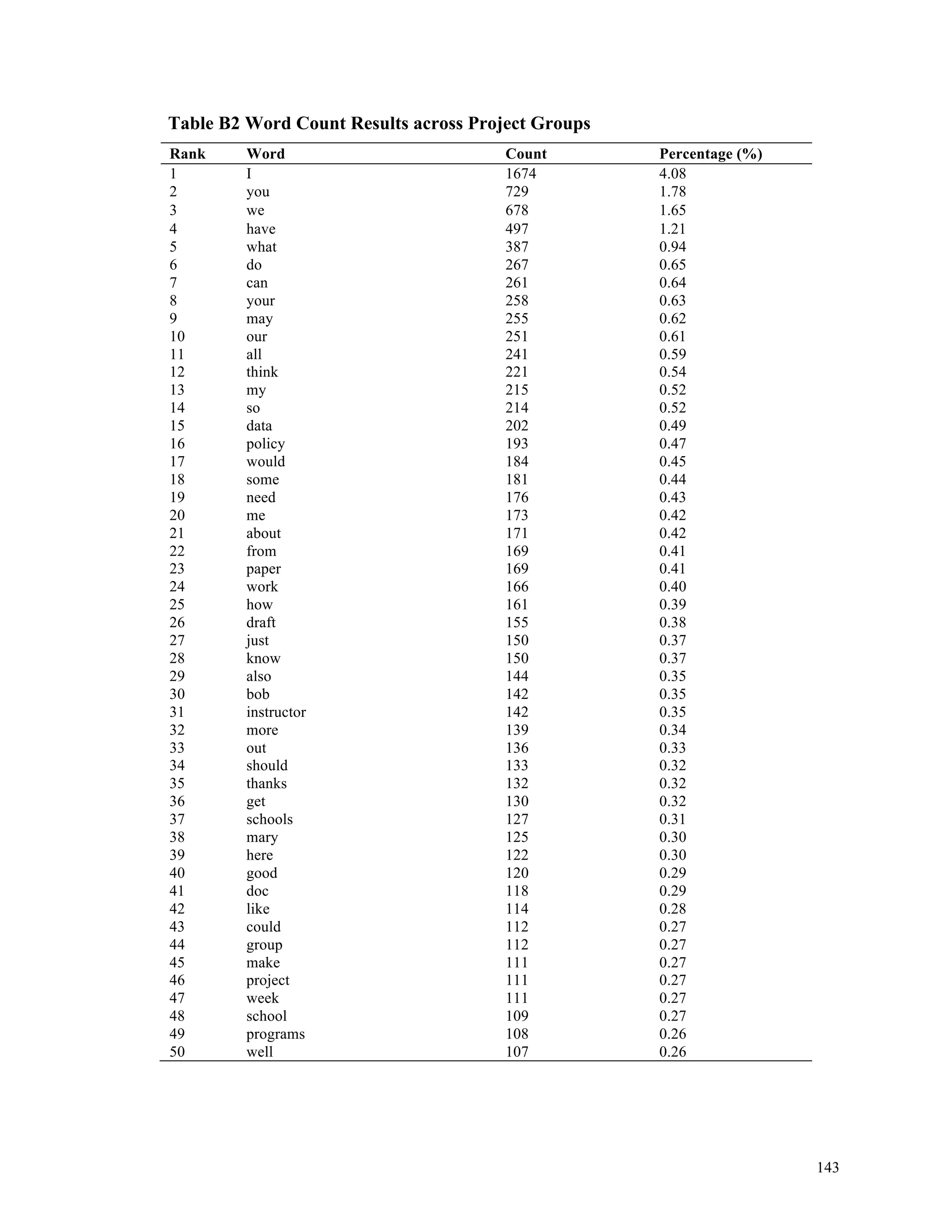

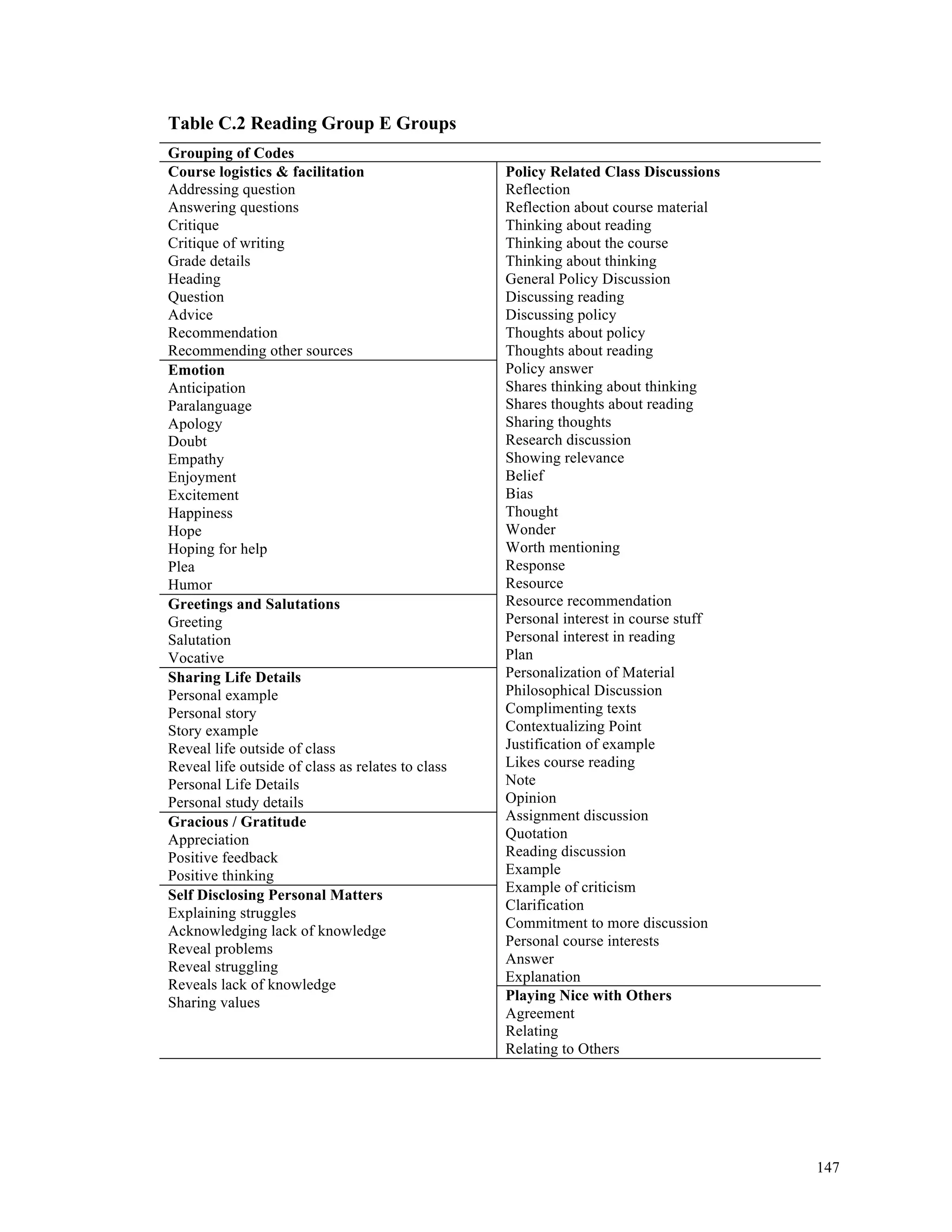

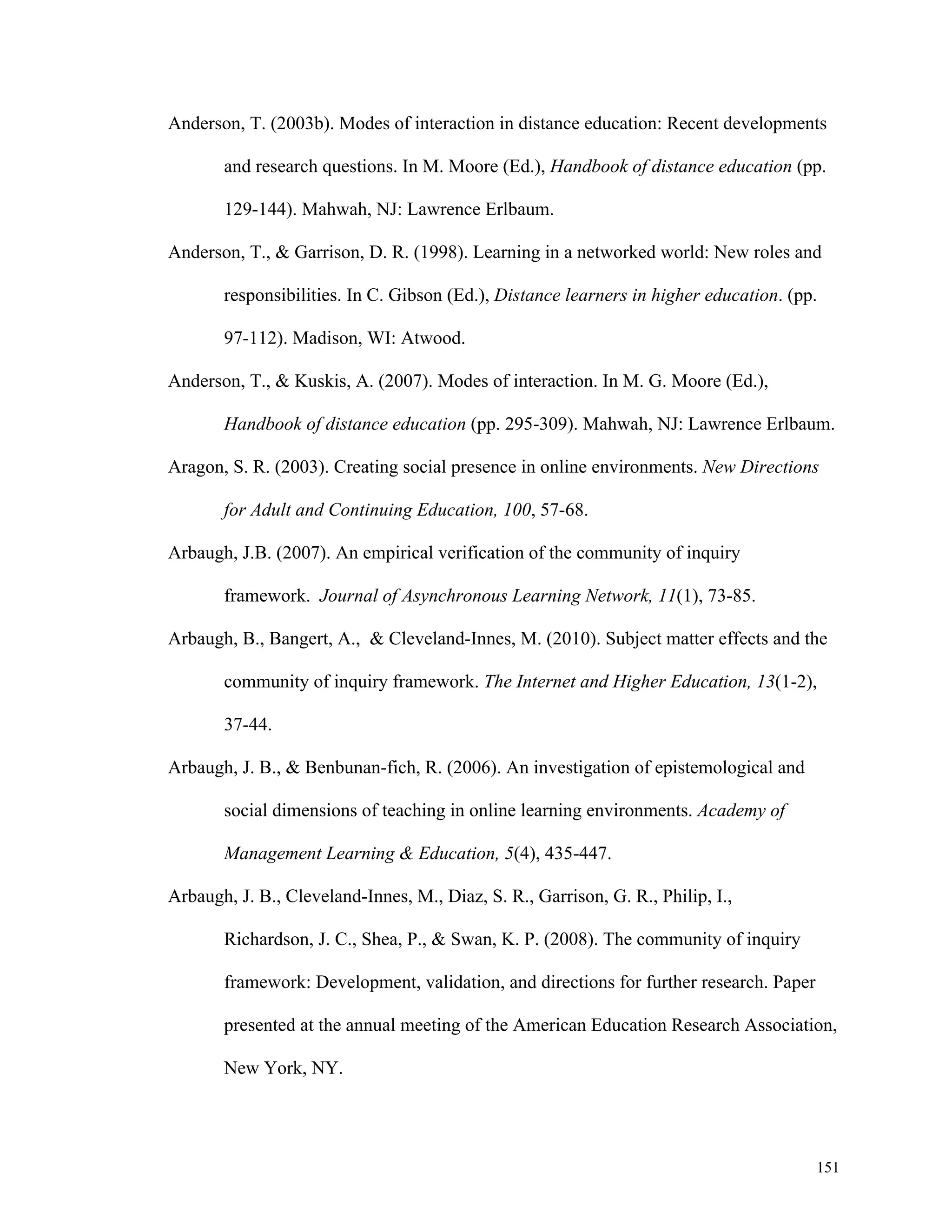

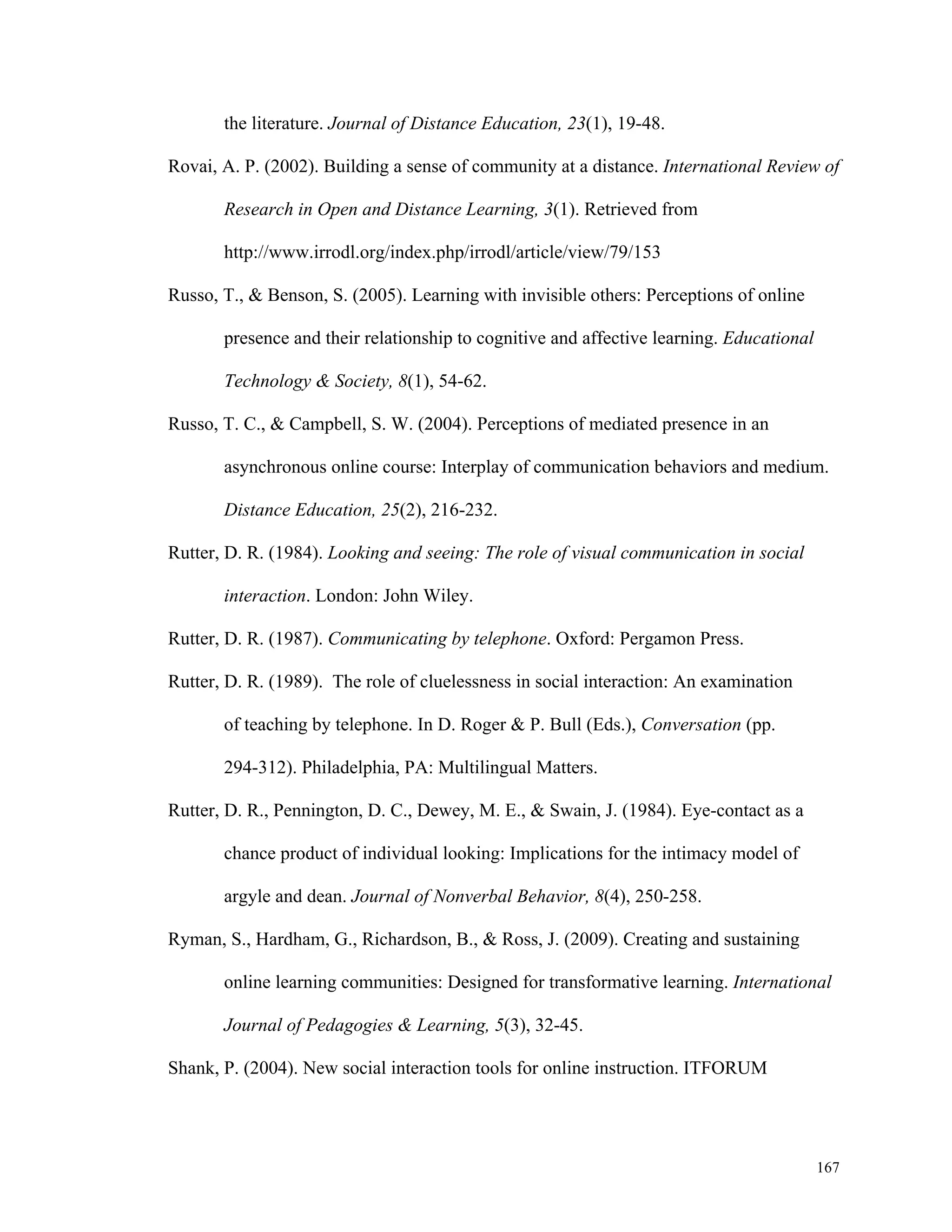

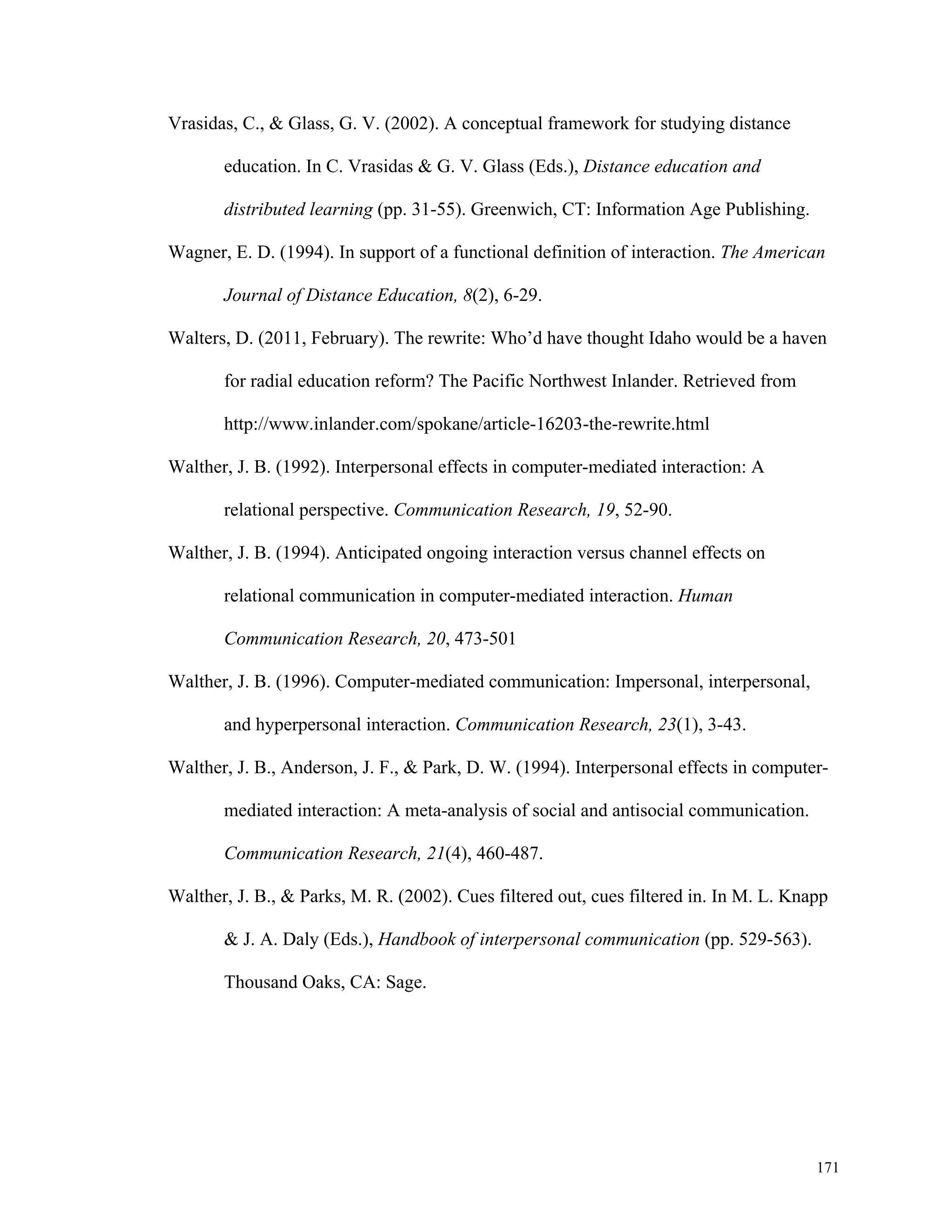

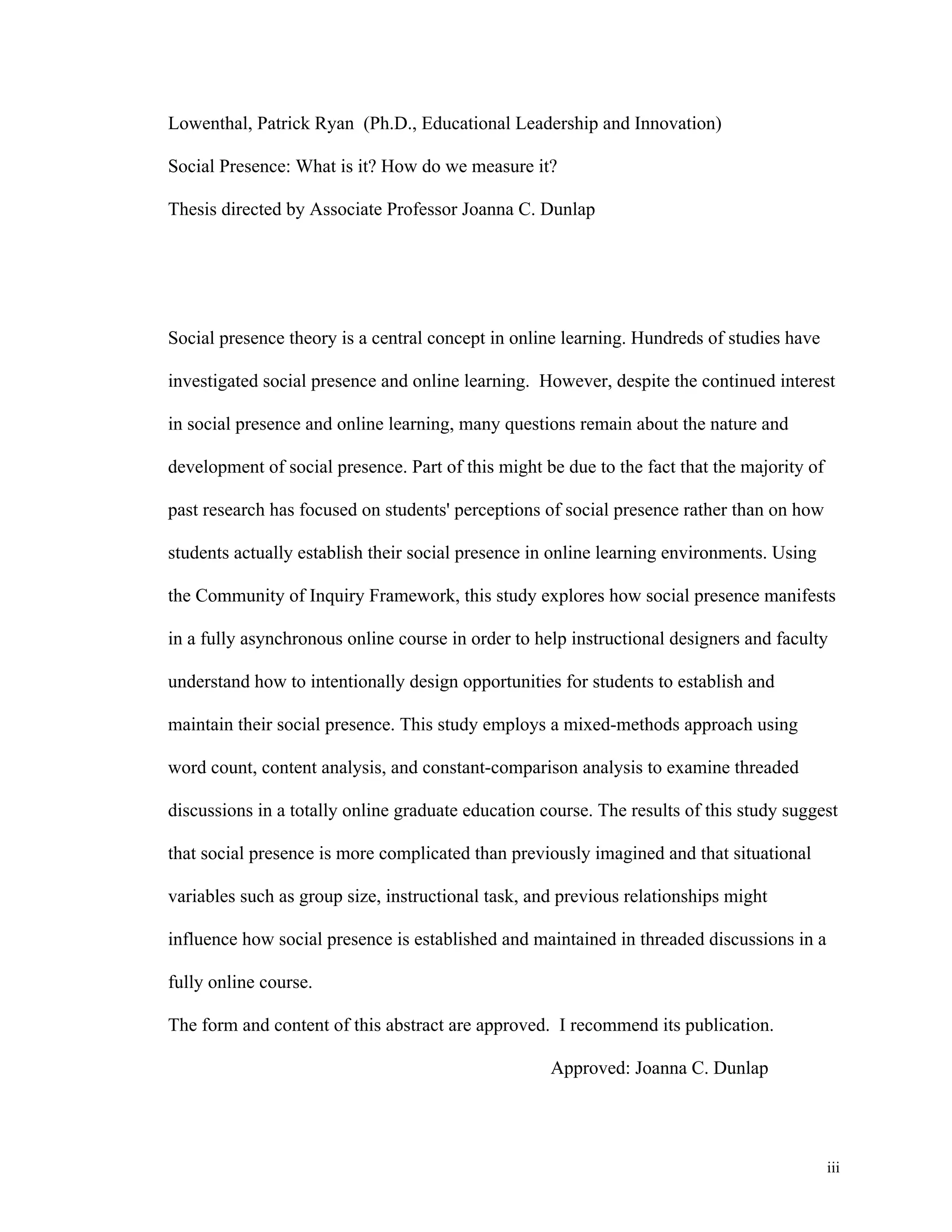

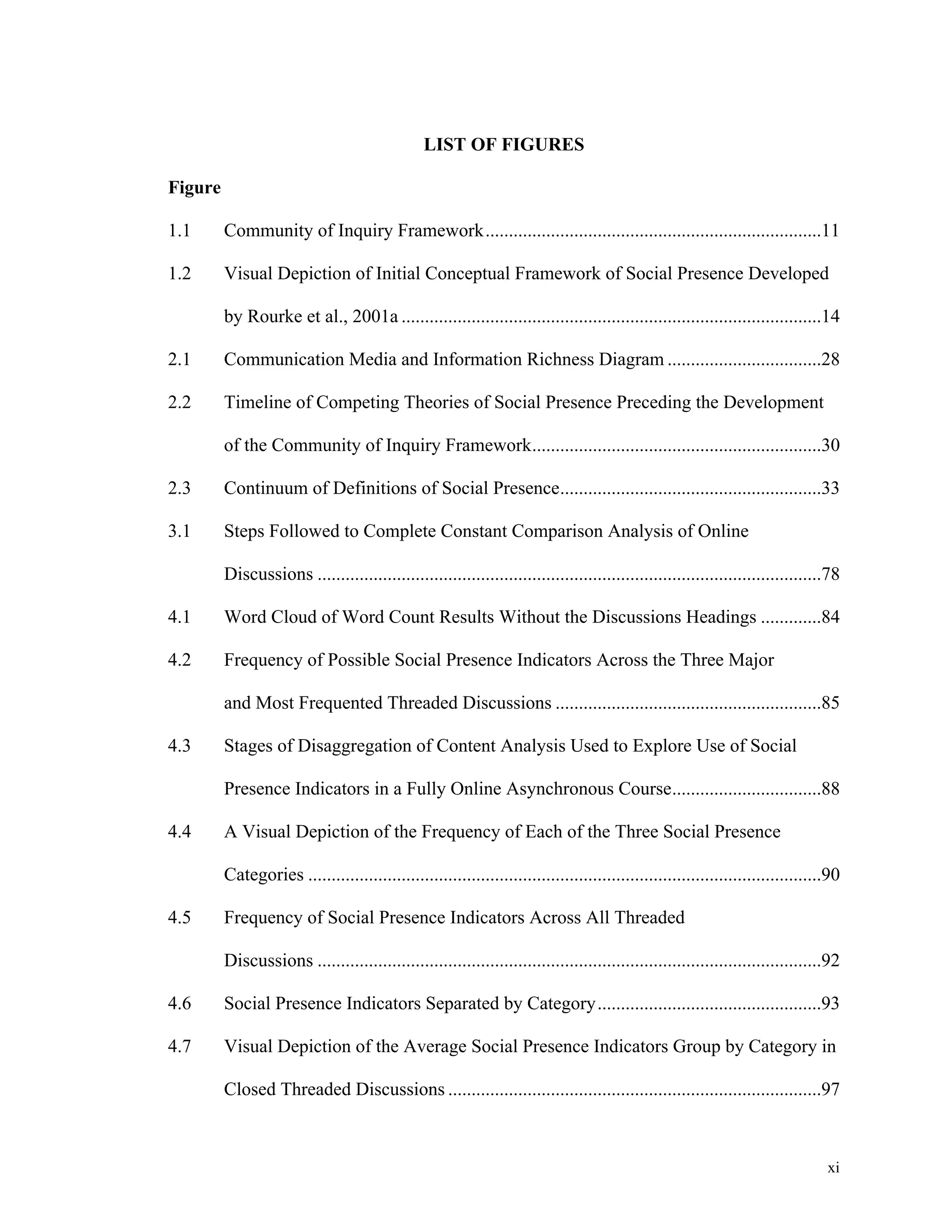

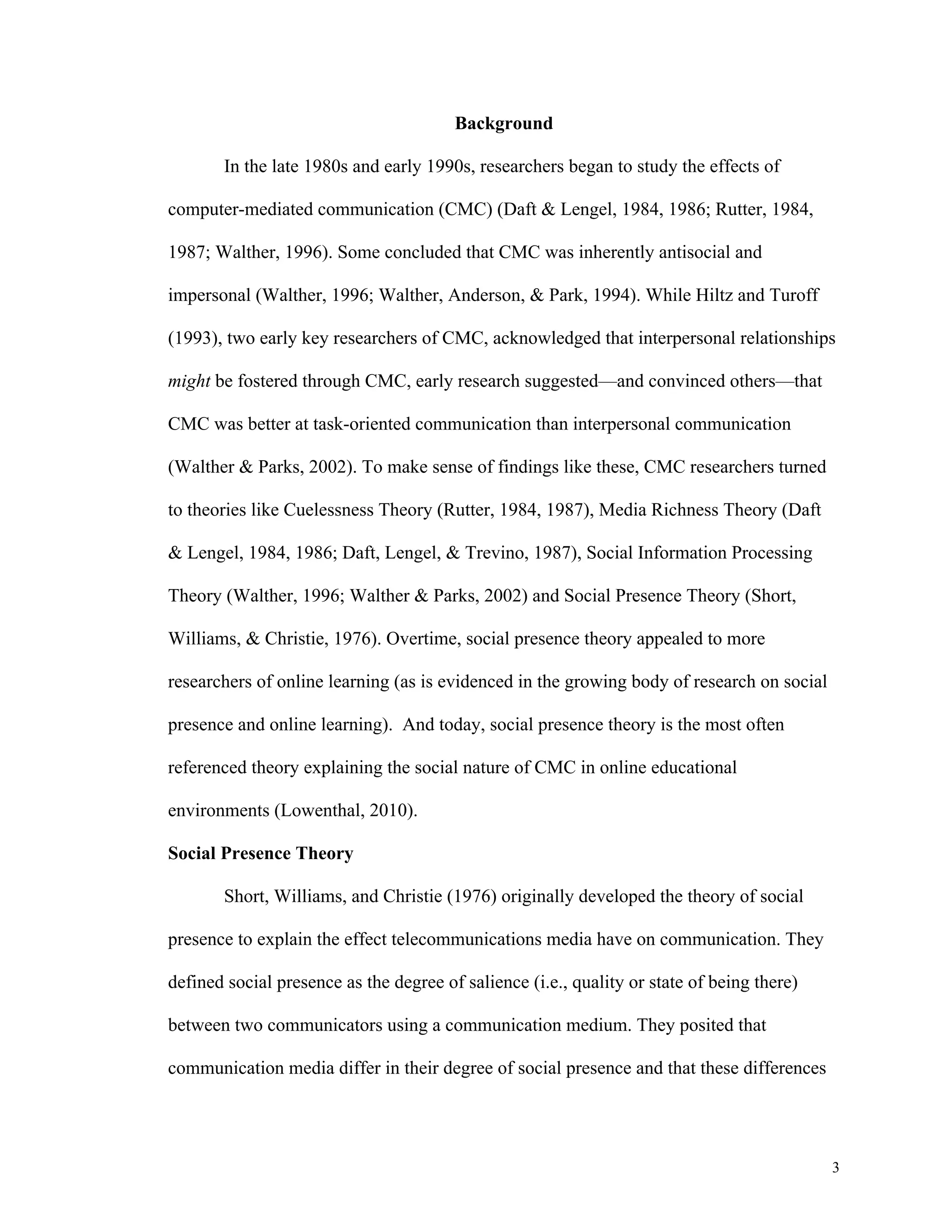

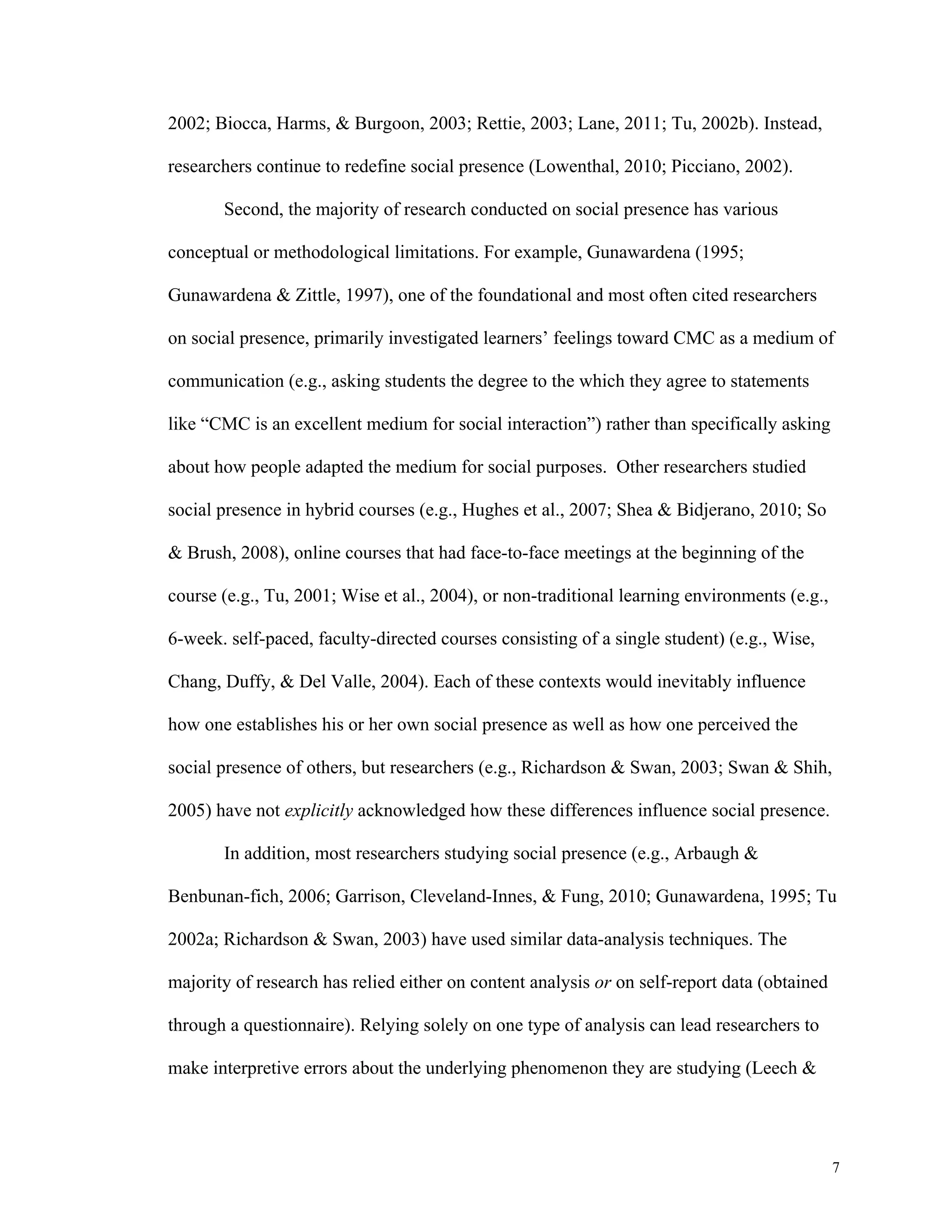

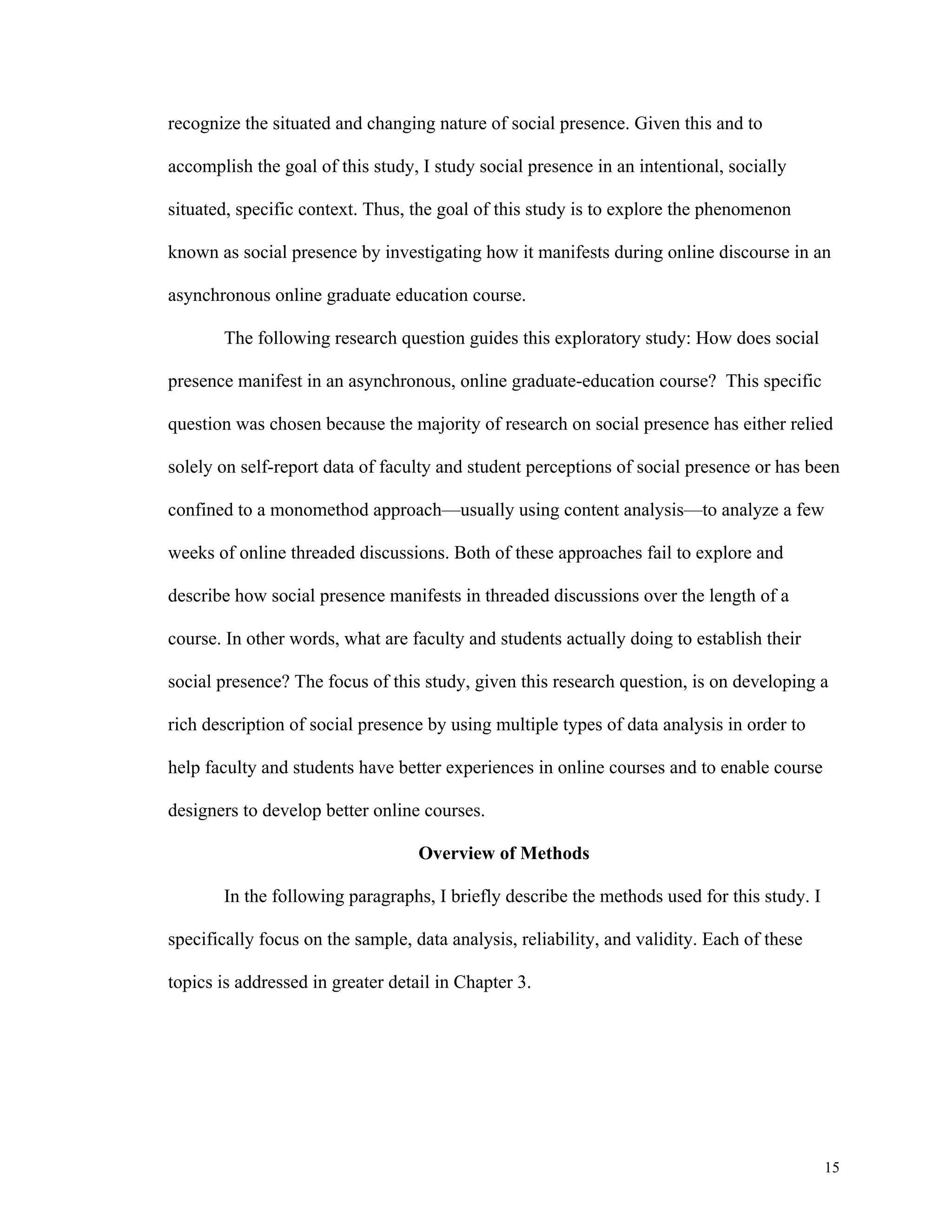

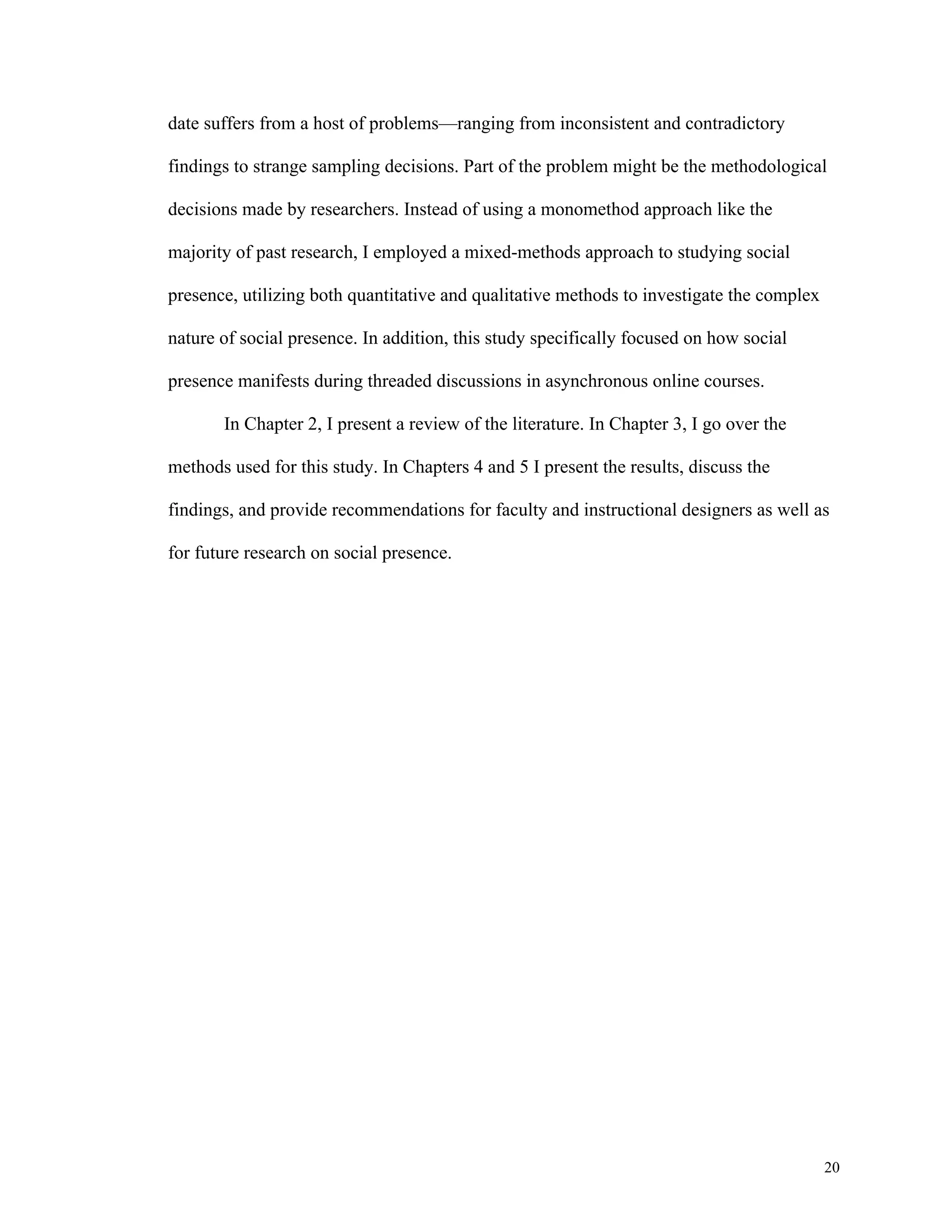

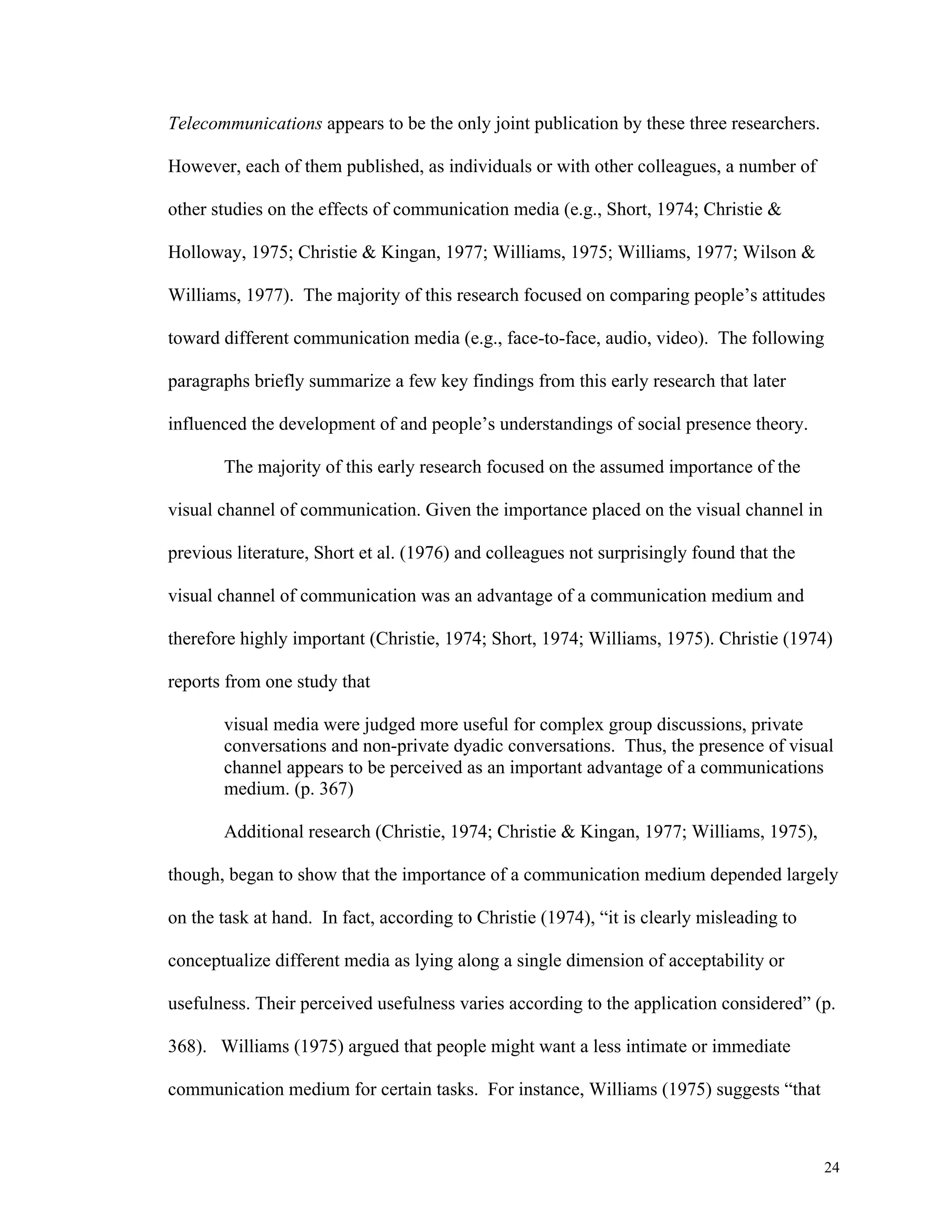

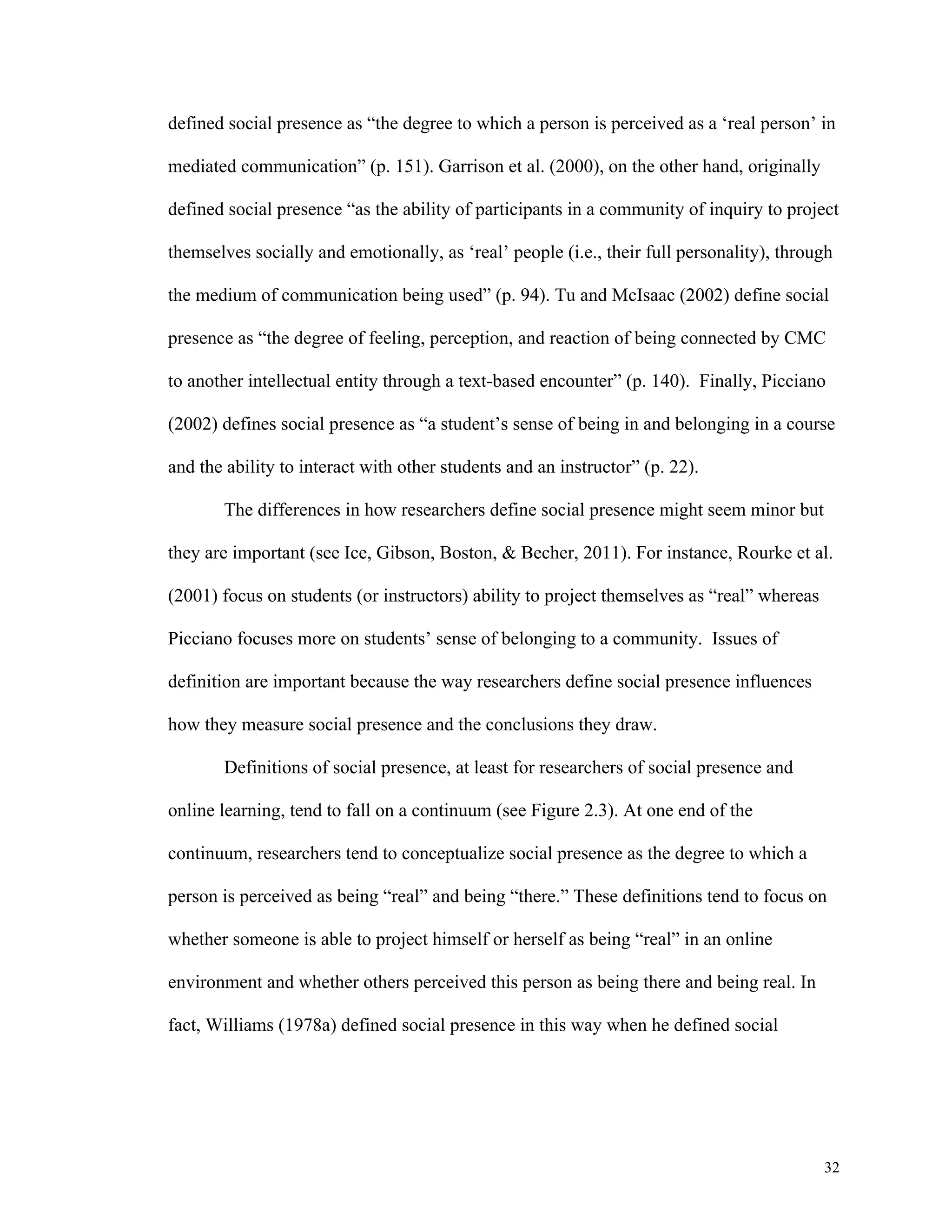

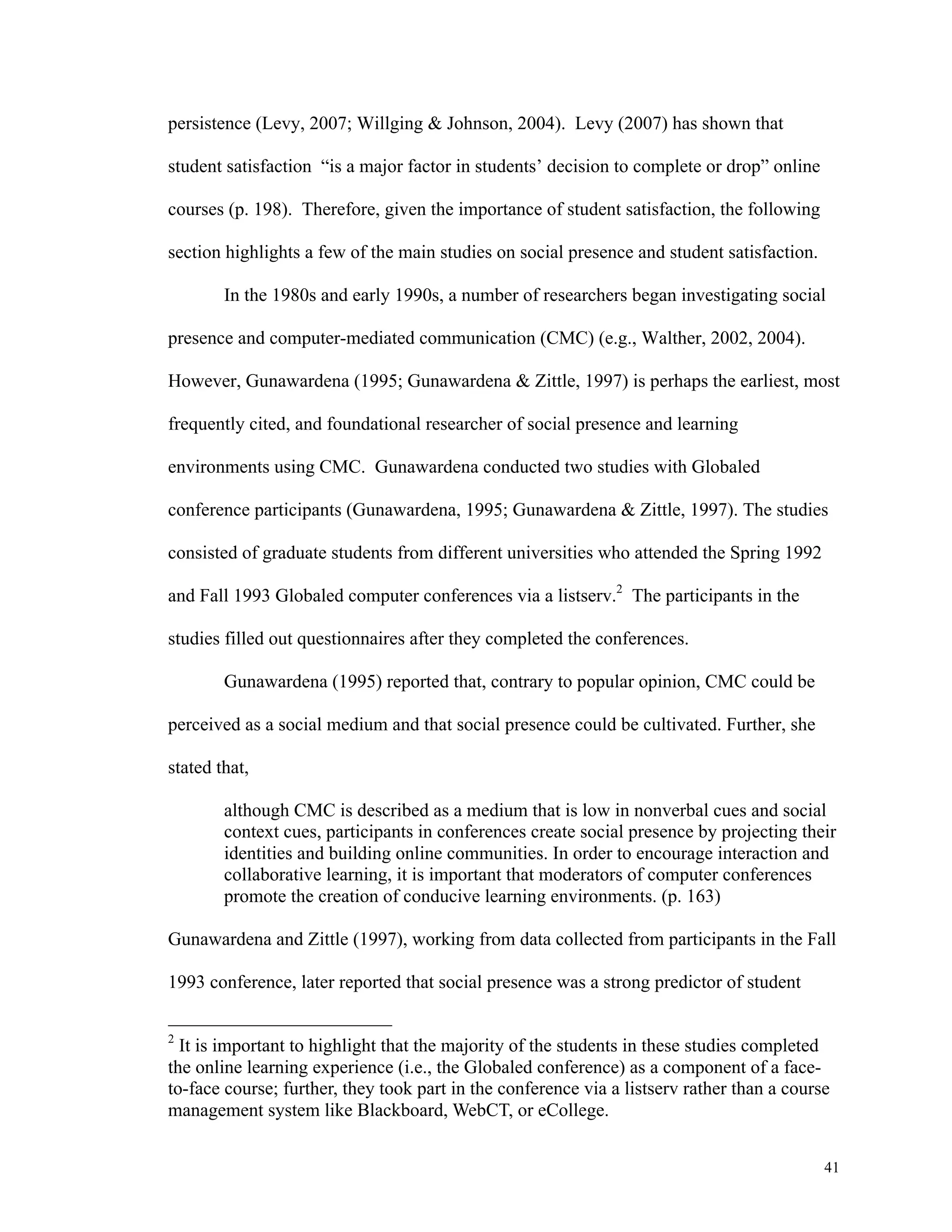

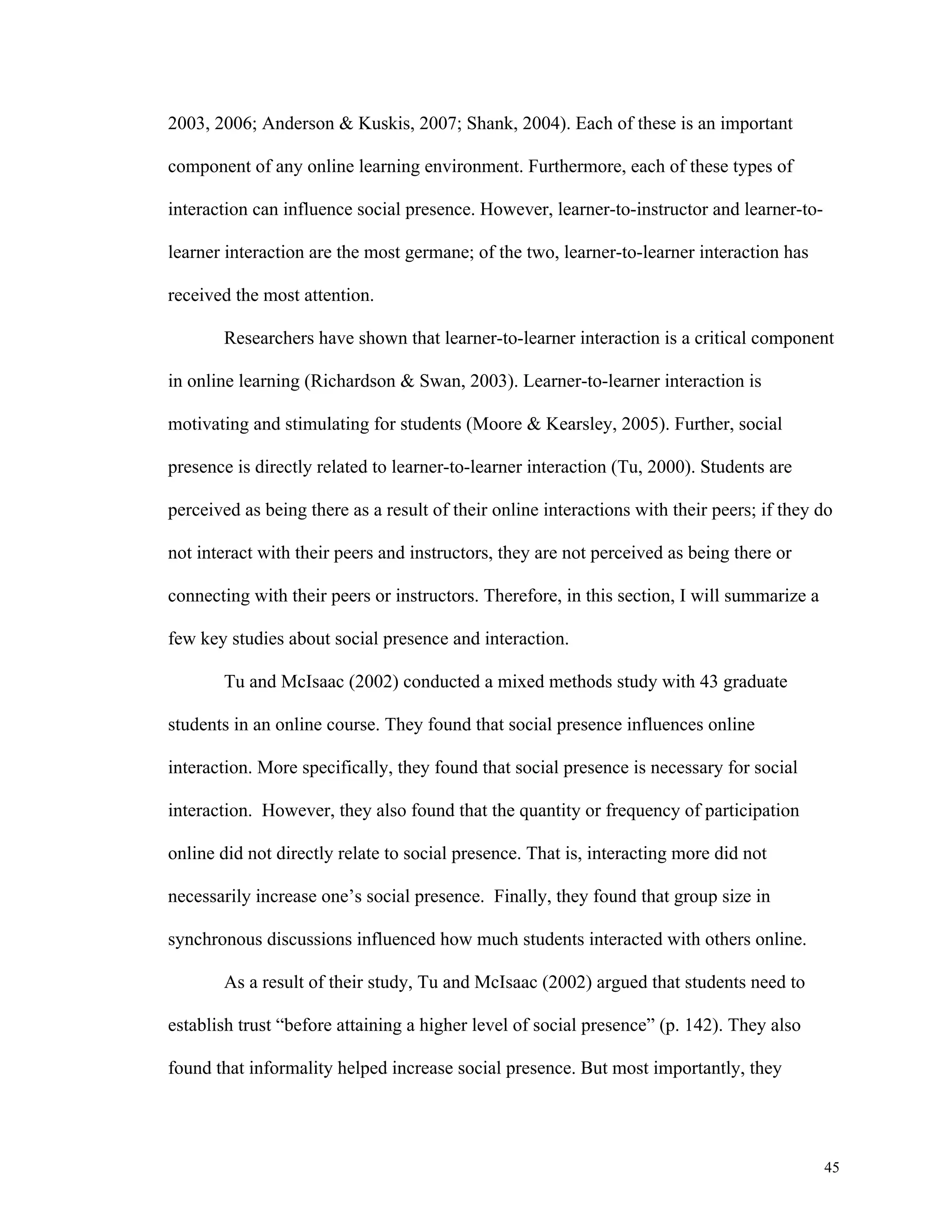

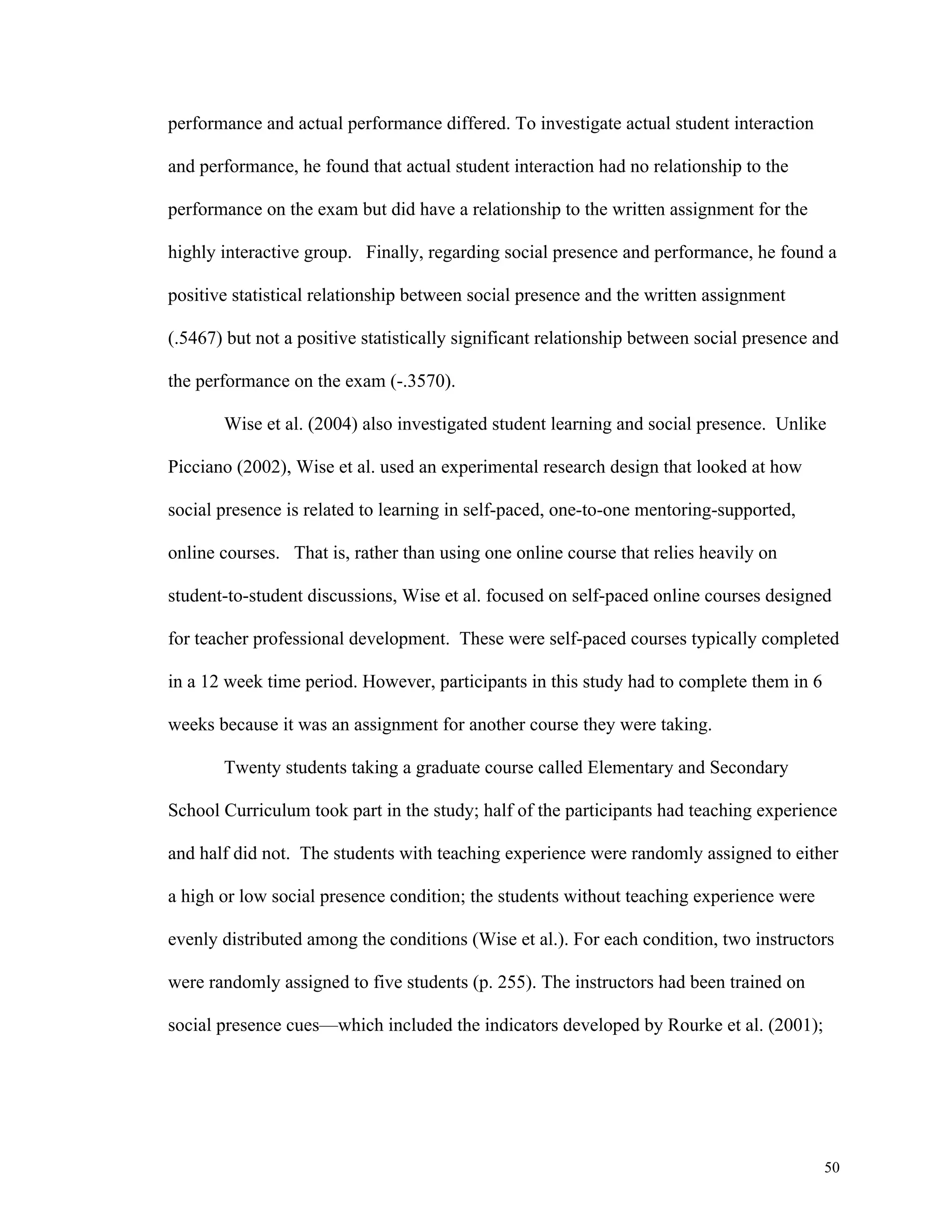

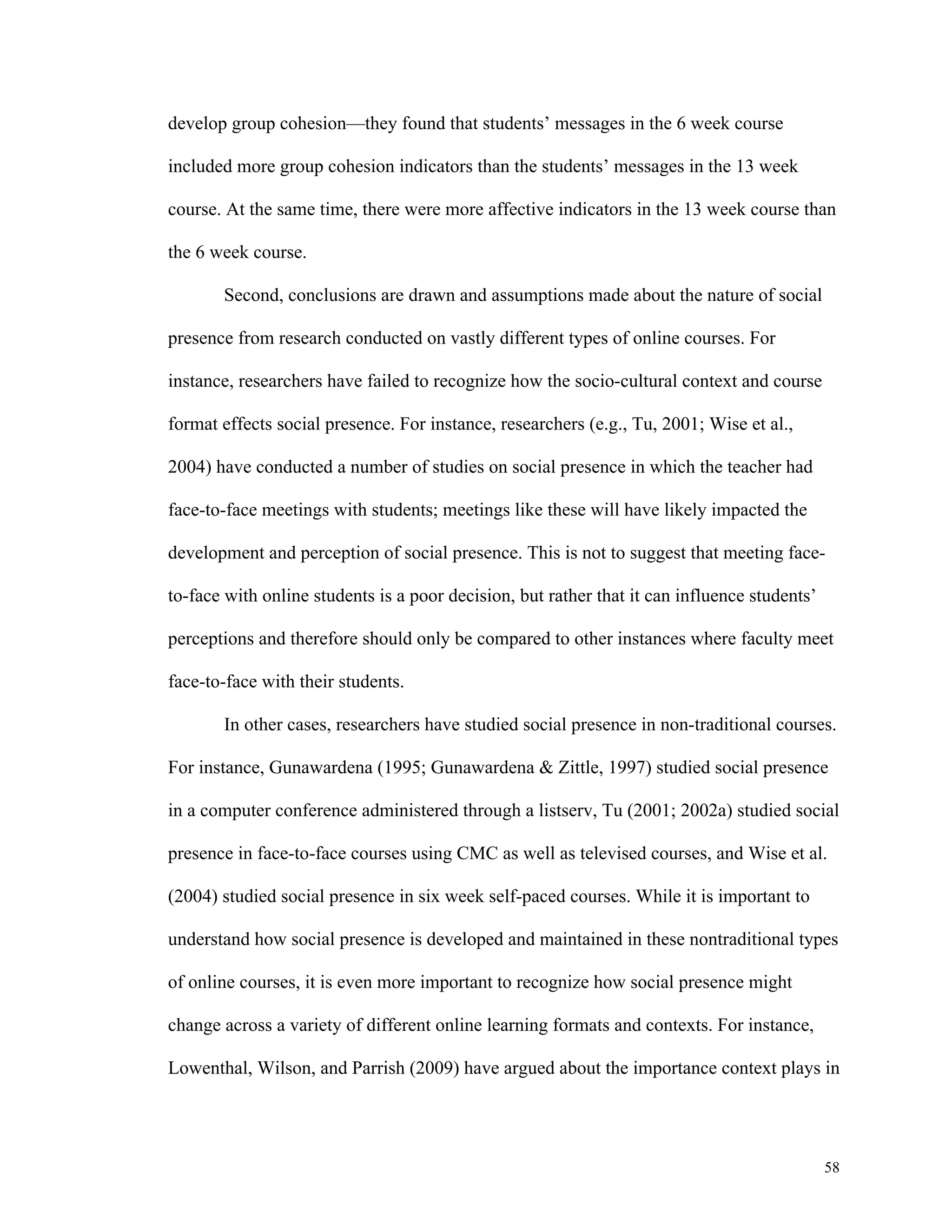

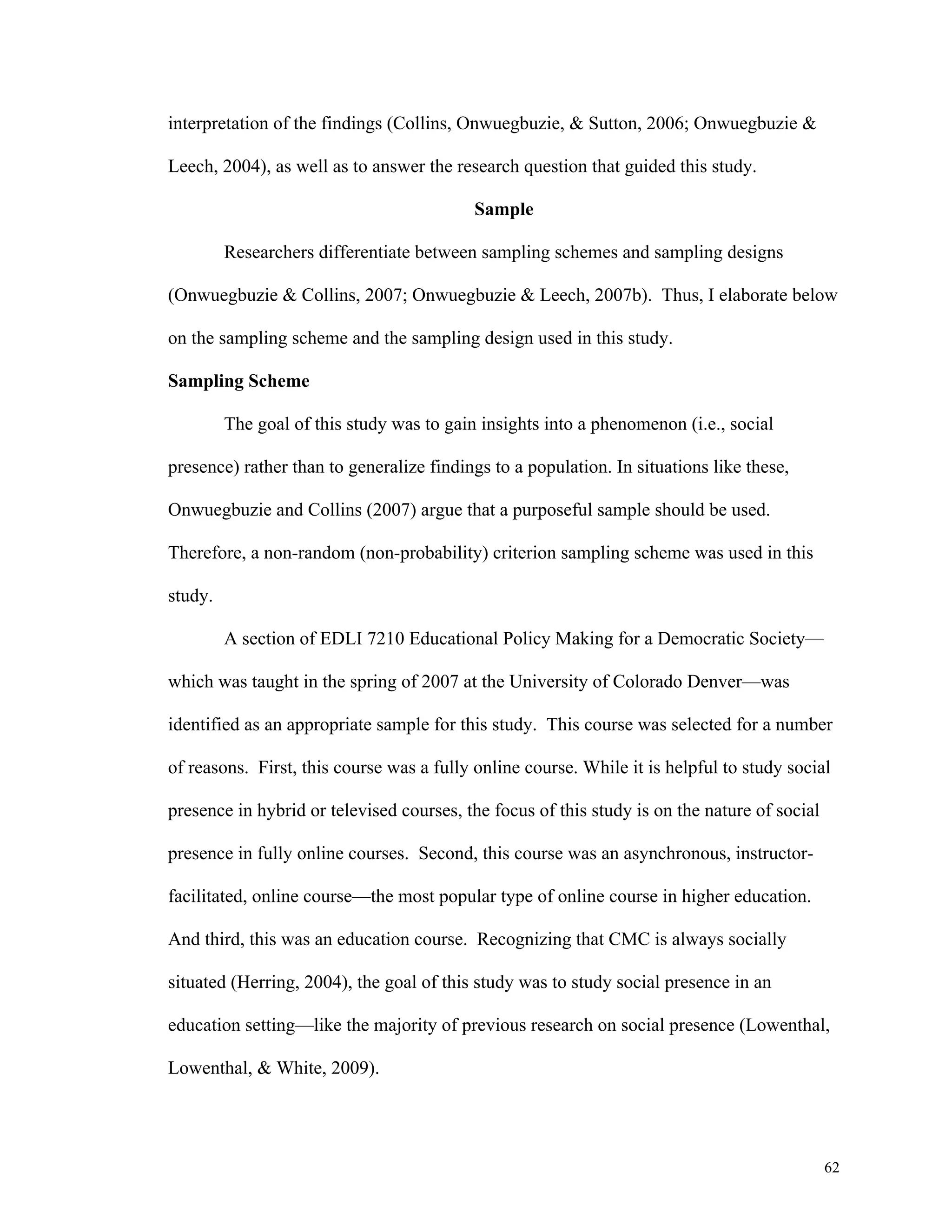

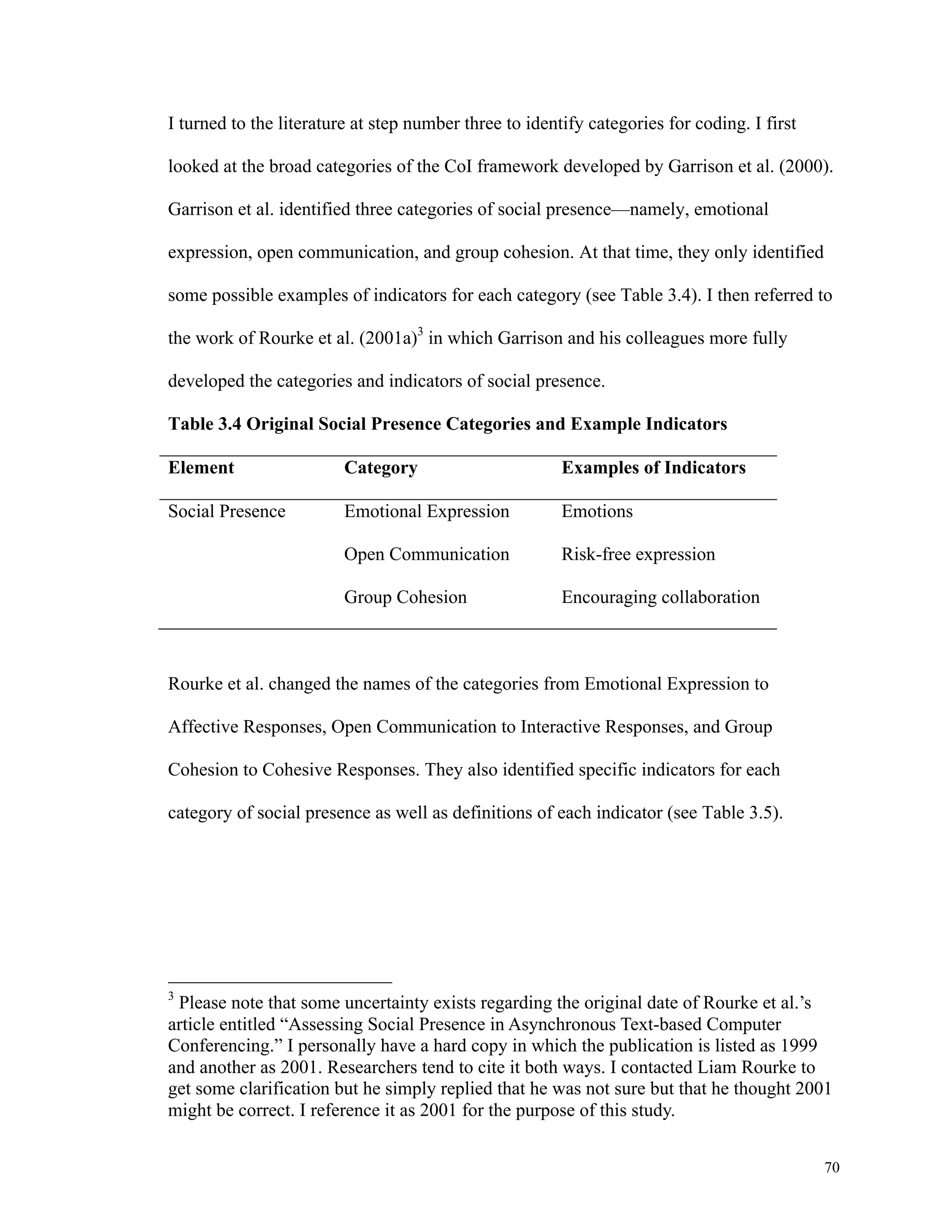

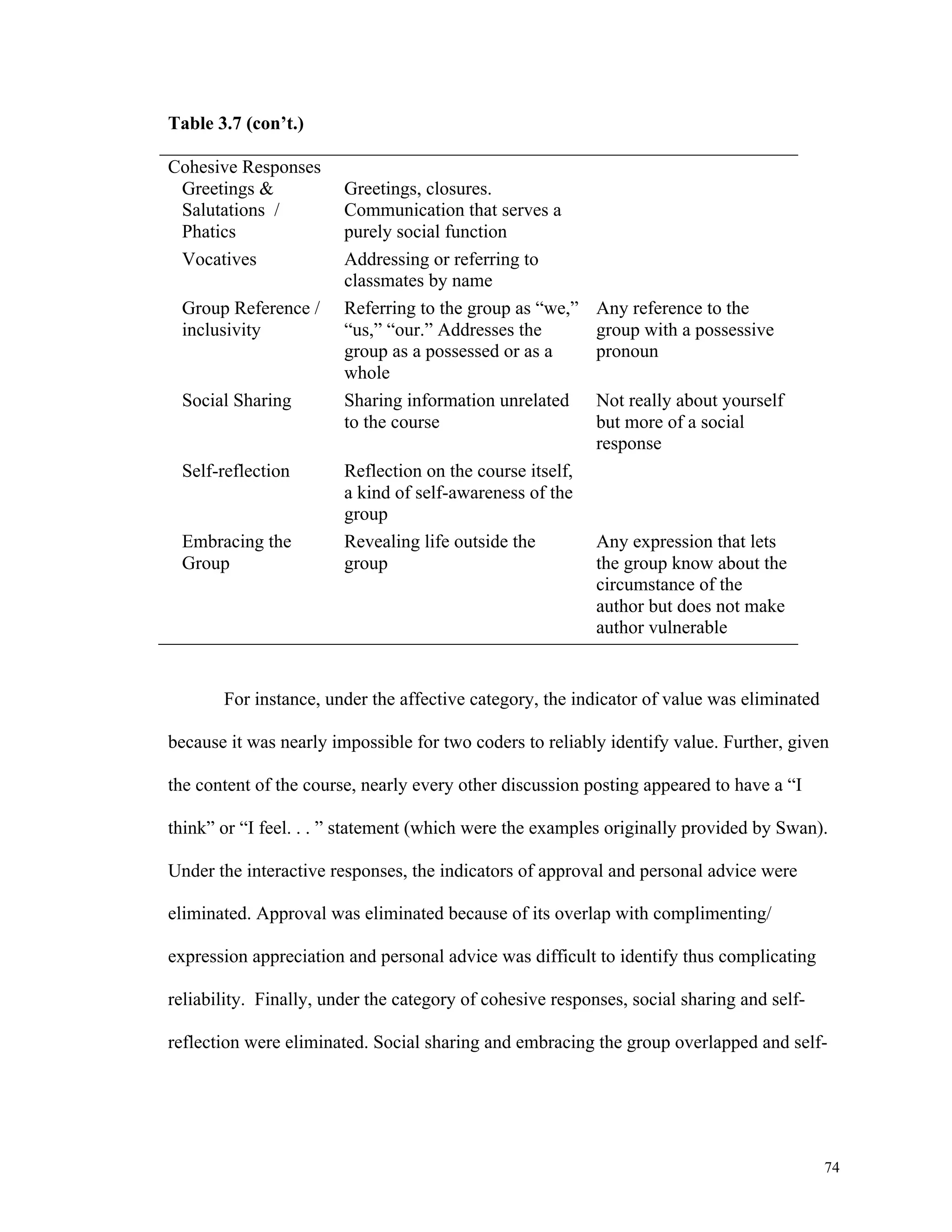

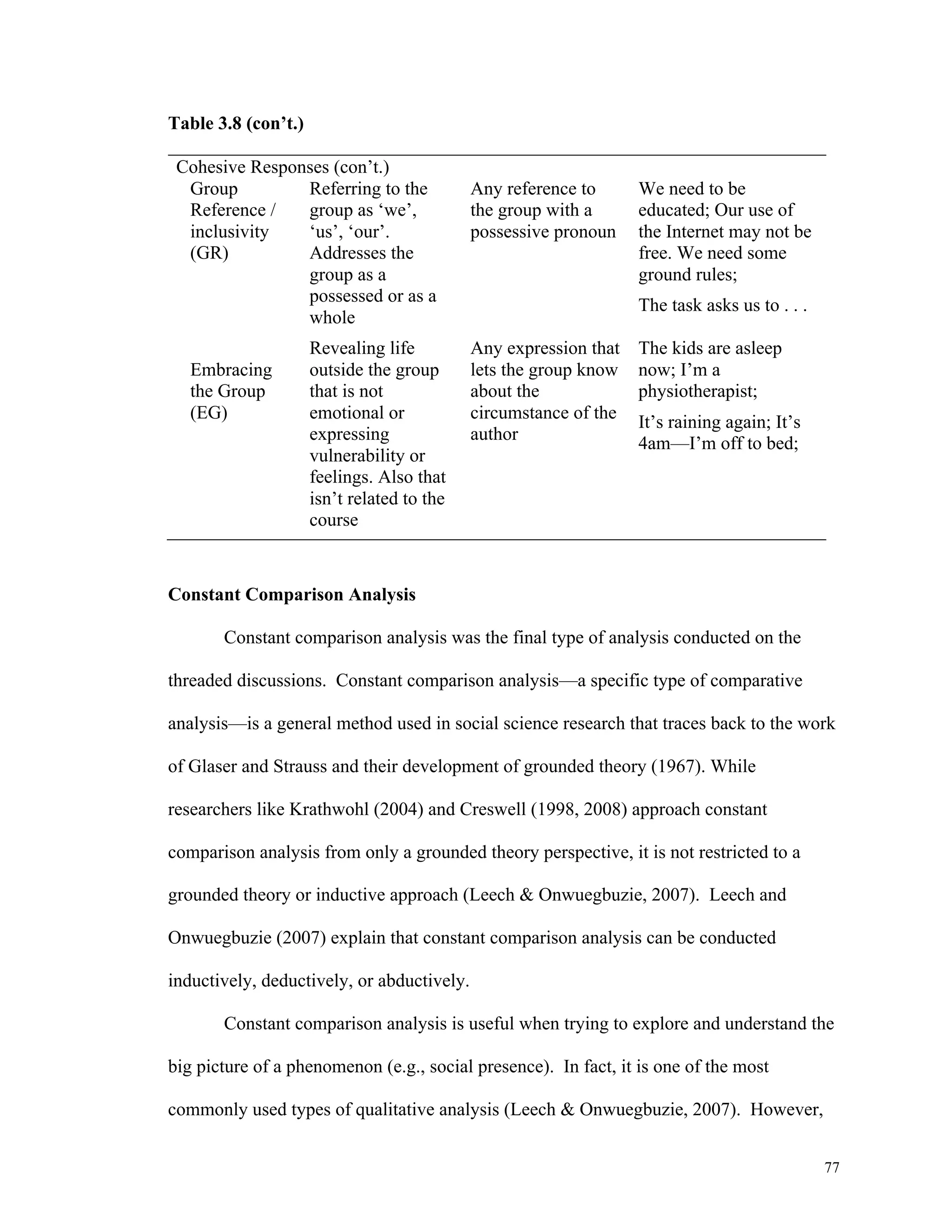

![researchers of CMC rarely use it to analyze online course discussions, most likely due to

78

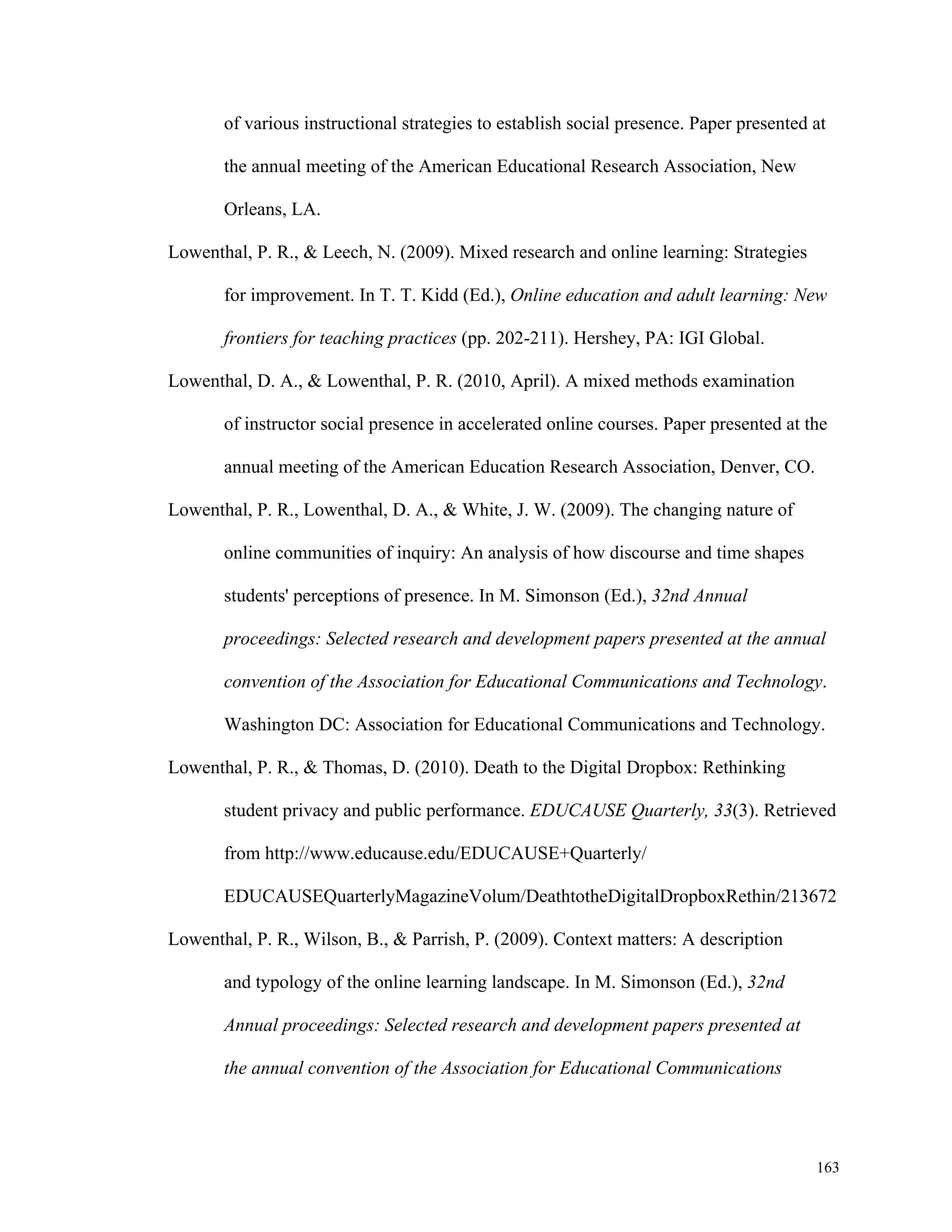

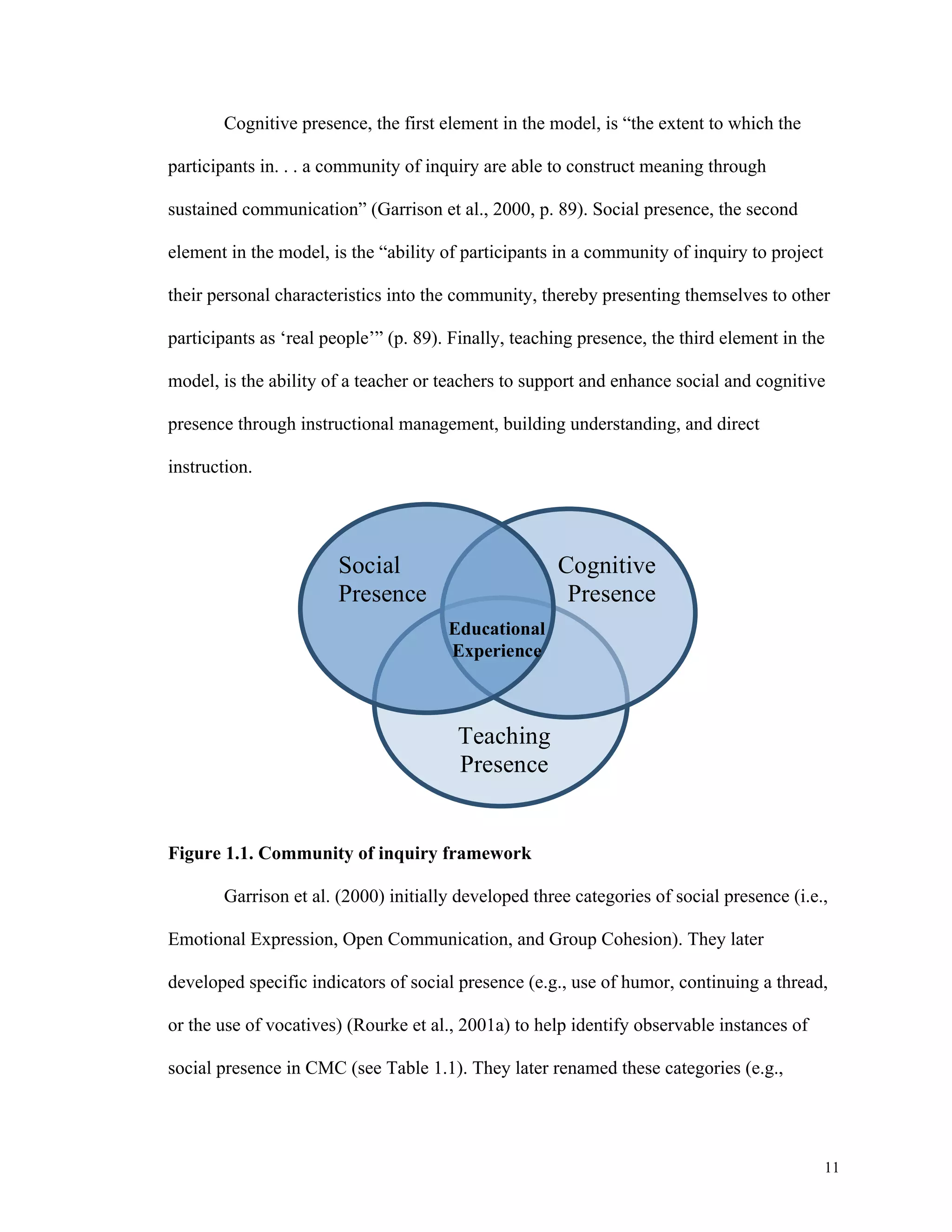

the time involved to conduct this type of analysis. It was used in this study to dig more

deeply into the threaded discussions to understand better the nature of social presence. To

conduct constant comparison analysis, I read the entire threaded discussion and

partitioned each meaningful unit into small chunks. I then labeled each chunk with a code

while constantly comparing new codes with previous ones. I then grouped the codes

together. Once I grouped the codes together, I identified themes that emerged from the

data. Figure 3.1 outlines the steps I took with examples from a previous study I

conducted.

Step 1. Read the discussion post

Hello everyone! I love the educational environments you have created this week. Educators and

students should always be the ones who create our schools. It is inspirational to see so many of you

create from the schools you have been in or are currently in. Thanks for your creativity! Dr. Deb C.

Step 2. Chunk the discussion post into meaningful units

[Hello everyone!] [I love the educational environments you have created this week.] [Educators

and students should always be the ones who create our schools.] [It is inspirational to see so many

of you create from the schools you have been in or are currently in.] [Thanks for your creativity!]

[Dr. Deb C]

Step 3. Code each meaningful unit while constantly comparing new

codes with previous codes

[Hello everyone!] GREETING [I love the educational environments you have created this week.]

POSITIVE FEEDBACK [Educators and students should always be the ones who create our

schools.] ELABORATION / CLARIFICATION [It is inspirational to see so many of you create

from the schools you have been in or are currently in.] POSITIVE FEEDBACK [Thanks for your

creativity!] POSITIVE FEEDBACK [Dr. Deb C] CLOSING REMARK](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3506428-libre-141017143206-conversion-gate01/75/SOCIAL-PRESENCE-WHAT-IS-IT-HOW-DO-WE-MEASURE-IT-93-2048.jpg)