Cluster analysis is an unsupervised machine learning technique that groups similar data objects into clusters. It finds internal structures within unlabeled data by partitioning it into groups based on similarity. Some key applications of cluster analysis include market segmentation, document classification, and identifying subtypes of diseases. The quality of clusters depends on both the similarity measure used and how well objects are grouped within each cluster versus across clusters.

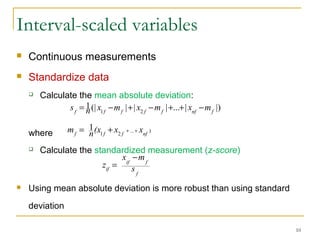

![Ordinal Variables

An ordinal variable can be discrete or continuous

Order is important, e.g., rank

Can be treated like interval-scaled

replace xif by their rank

map the range of each variable onto [0, 1] by replacing i-th object in

the f-th variable by

compute the dissimilarity using methods for interval-scaled

variables

16

1

1

−

−

=

f

if

if M

r

z

},...,1{ fif

Mr ∈](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3-150507081233-lva1-app6892/85/3-1-clustering-16-320.jpg)