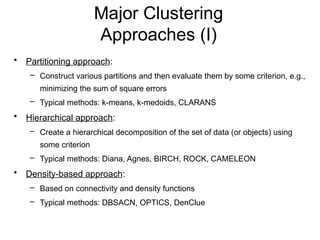

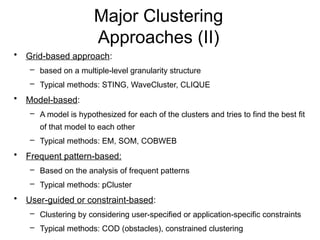

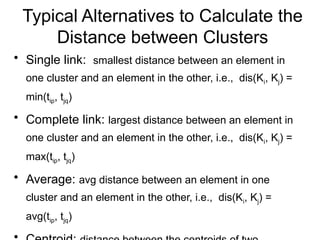

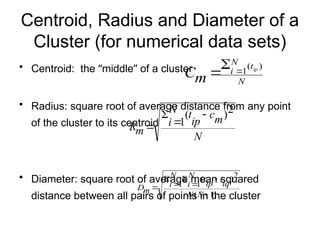

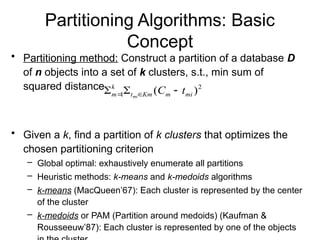

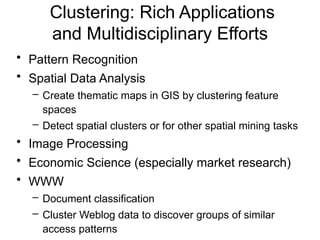

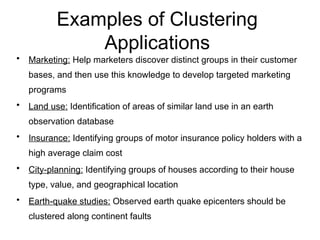

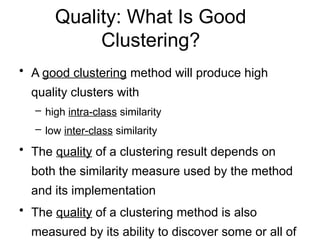

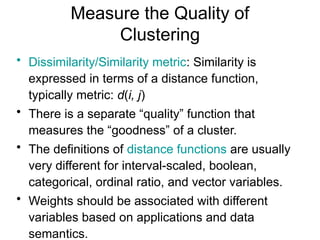

Cluster analysis is a method for grouping similar data objects based on their characteristics without pre-defined classes, utilized in various fields like marketing, land use, and city planning. A good clustering method results in high intra-class similarity and low inter-class similarity, with an emphasis on measuring the quality of clusters through distance functions and appropriate metrics. Different clustering approaches include partitioning, hierarchical, density-based, grid-based, and model-based methods, each with distinct algorithms and applications.

![Ordinal Variables

• An ordinal variable can be discrete or continuous

• Order is important, e.g., rank

• Can be treated like interval-scaled

– replace xif by their rank

– map the range of each variable onto [0, 1] by replacing

i-th object in the f-th variable by

– compute the dissimilarity using methods for interval-

scaled variables

1

1

f

if

if M

r

z

}

,...,

1

{ f

if

M

r ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/clusteranalysis-240912064711-6f35d079/85/Cluster-Analysis-in-Business-Research-Methods-15-320.jpg)