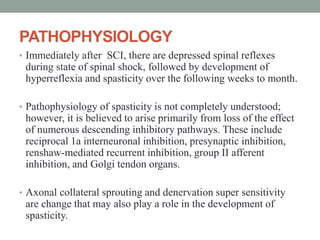

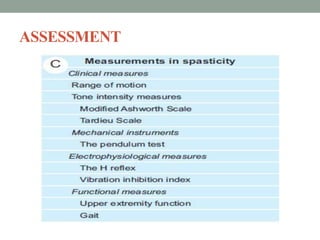

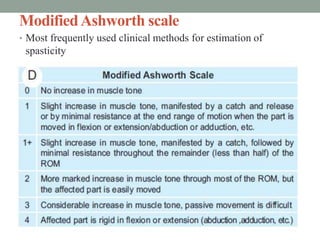

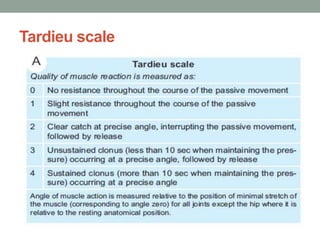

This document discusses spasticity, including its pathophysiology, assessment, and management.

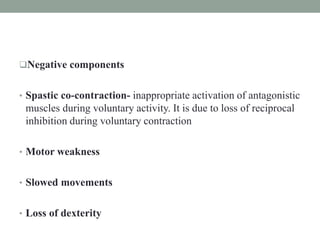

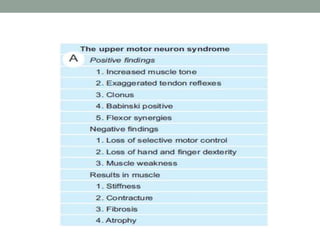

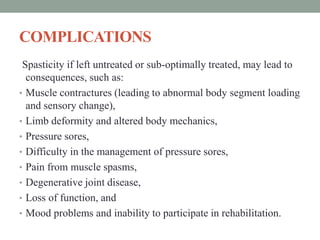

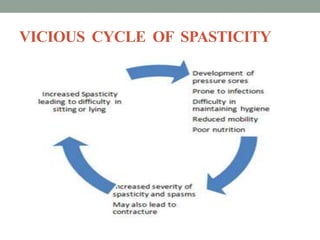

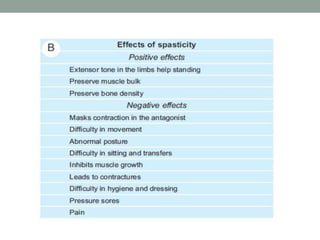

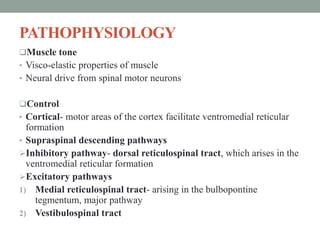

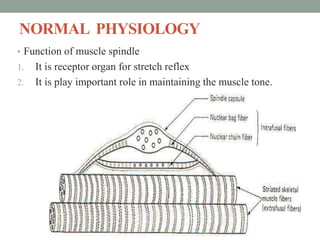

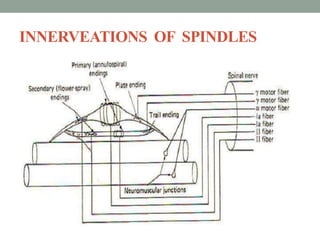

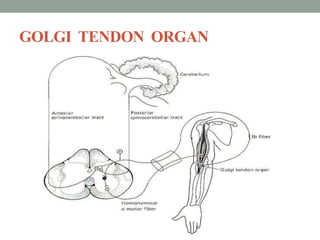

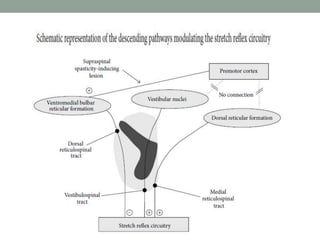

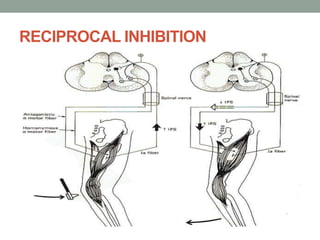

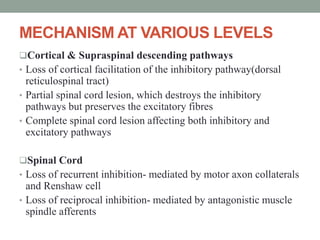

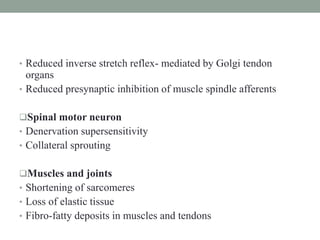

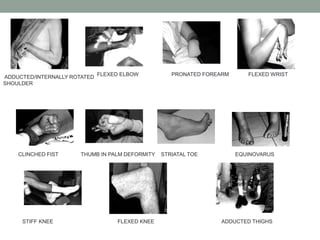

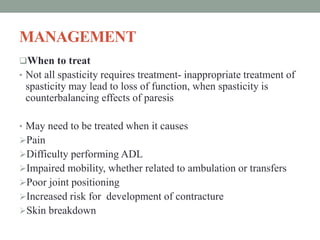

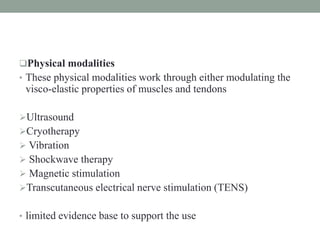

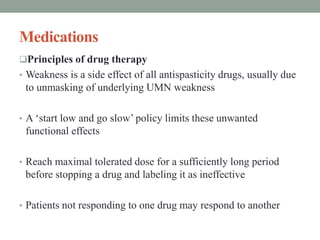

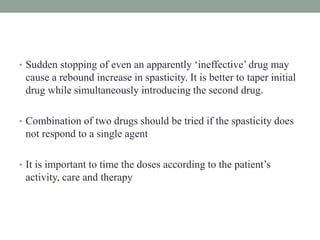

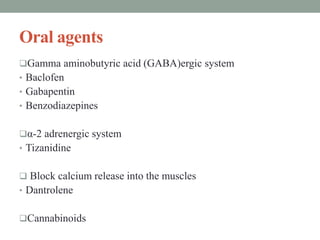

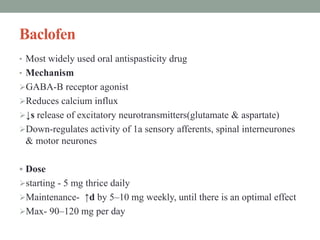

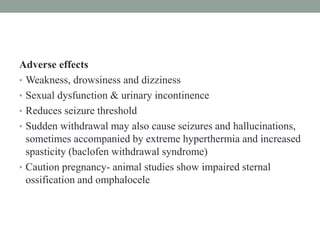

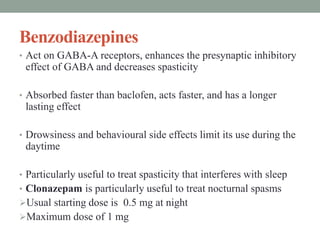

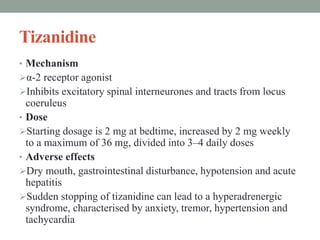

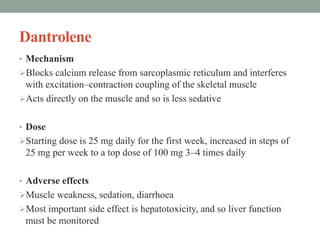

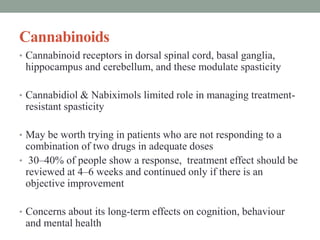

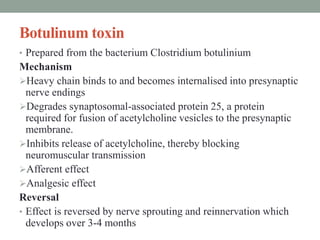

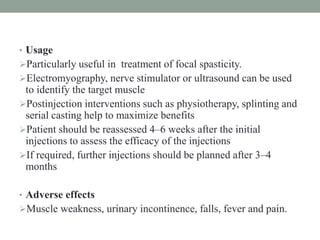

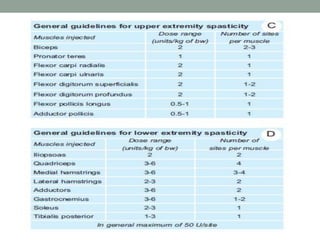

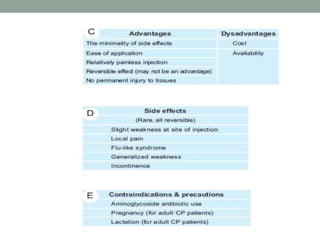

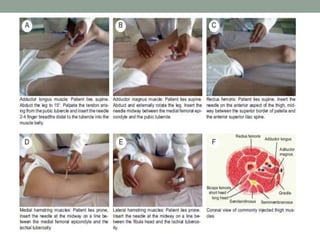

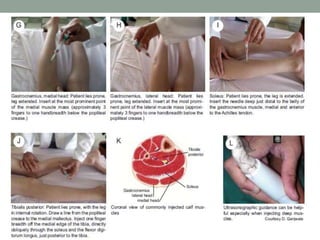

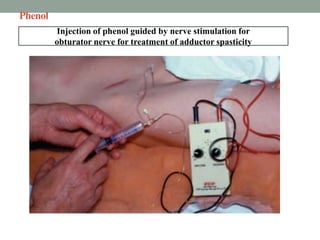

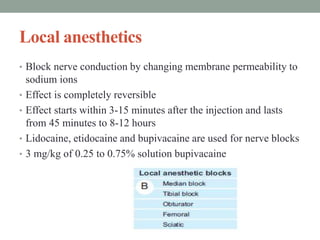

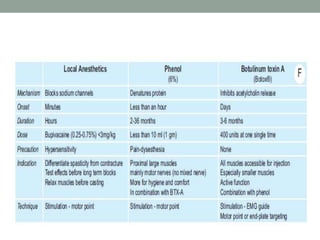

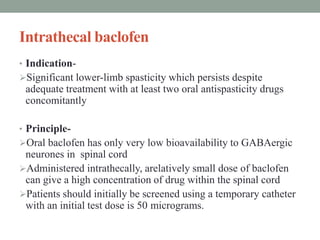

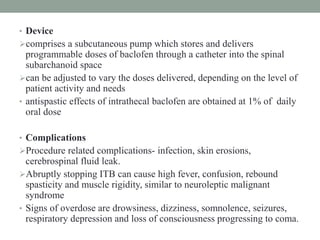

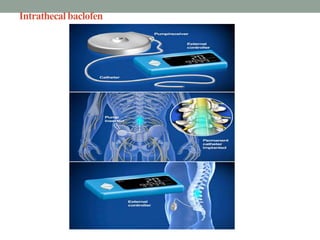

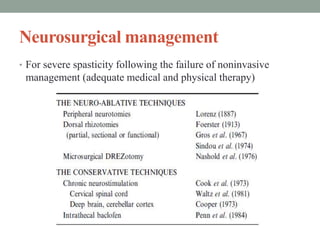

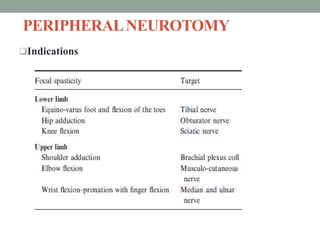

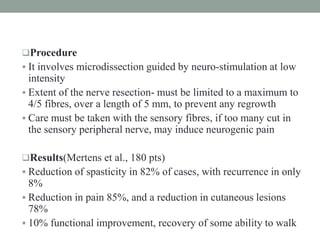

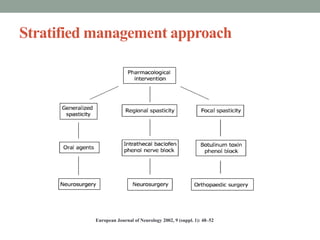

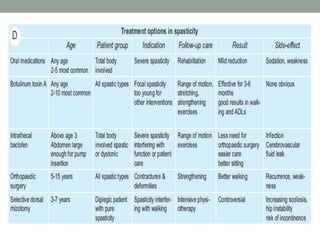

Spasticity is characterized by velocity-dependent increases in muscle tone and exaggerated reflexes due to hyper-excitability of the stretch reflex. It is caused by loss of inhibitory descending pathways in the spinal cord from upper motor neuron lesions. Management includes identifying triggers, passive stretching, exercises, medications like baclofen and botulinum toxin injections, and in severe cases nerve blocks or neurolysis using phenol or alcohol. The goal is to reduce spasticity-related pain and impairments while preventing complications like contractures.