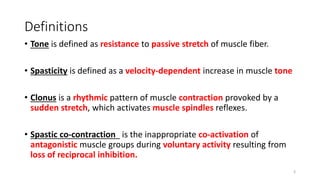

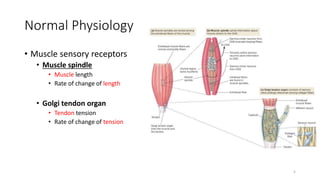

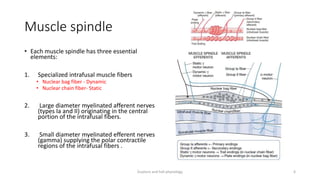

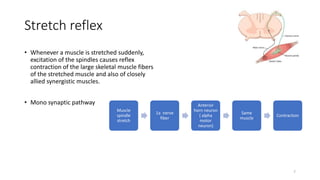

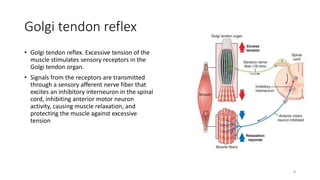

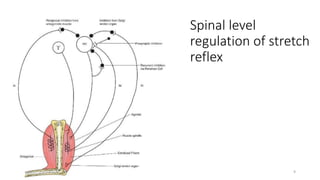

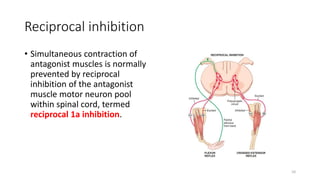

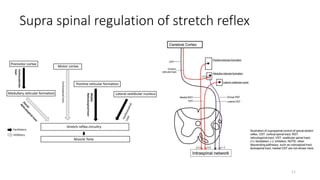

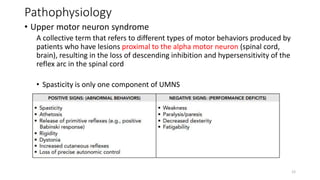

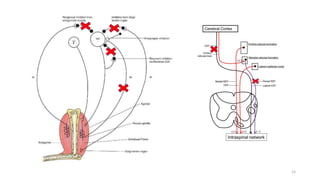

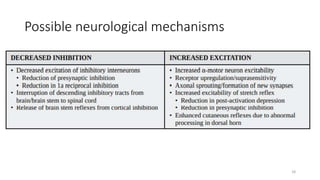

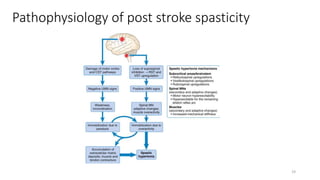

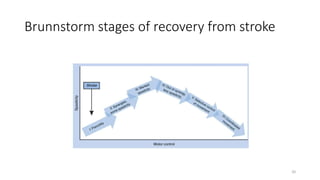

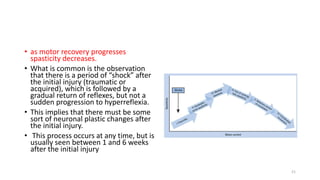

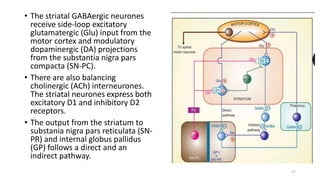

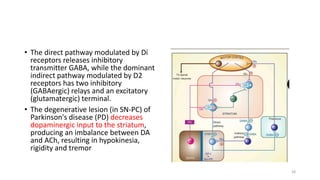

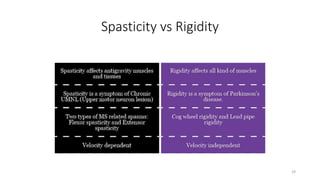

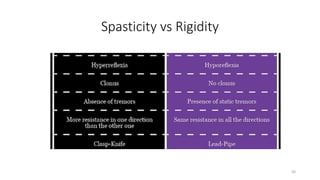

The document presents a detailed overview of spasticity, its pathophysiology, and differences with rigidity and flexor spasms, emphasizing its role within upper motor neuron syndrome. It discusses the physiological mechanisms, the impact of various conditions leading to spasticity, and the evolution of reflexes following spinal injuries. Additionally, it highlights the potential benefits and challenges posed by spasticity in patients, advocating for careful assessment to inform treatment strategies.