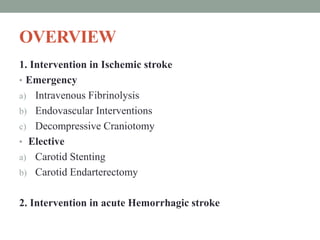

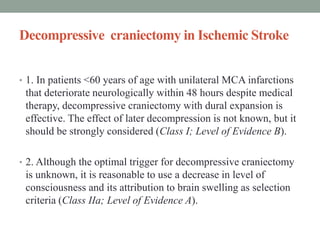

1. The document summarizes current stroke intervention strategies, including intravenous fibrinolysis (tPA), endovascular interventions like intra-arterial fibrinolysis and mechanical thrombectomy, and decompressive craniotomy.

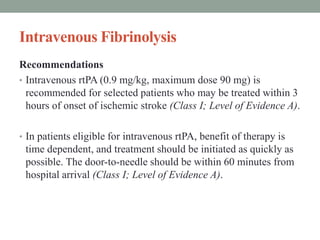

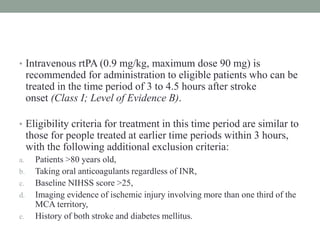

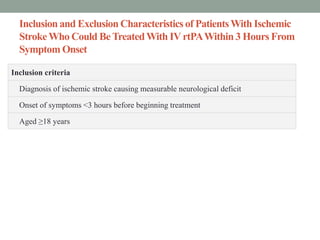

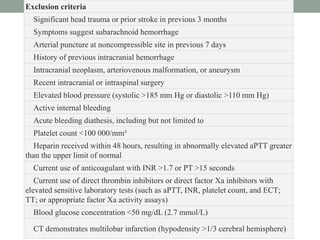

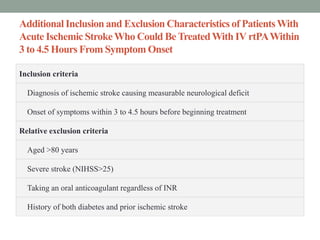

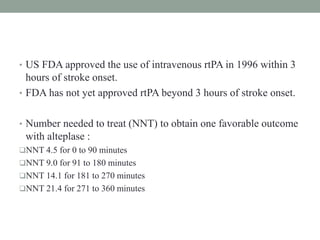

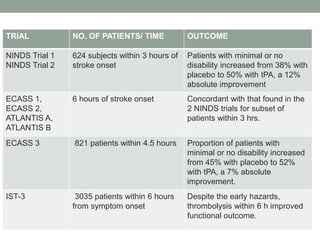

2. Intravenous tPA is recommended within 3 hours and may be considered within 3-4.5 hours for select patients. Several trials have demonstrated the benefits of intravenous tPA.

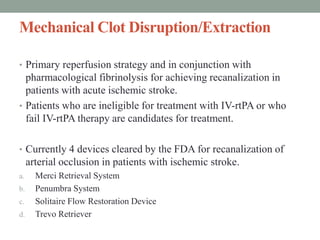

3. Intra-arterial fibrinolysis and mechanical thrombectomy are beneficial options for carefully selected patients not eligible for intravenous tPA or who have failed intravenous tPA. Recent trials show improved outcomes with newer mechanical thrombectomy devices compared to older technologies.

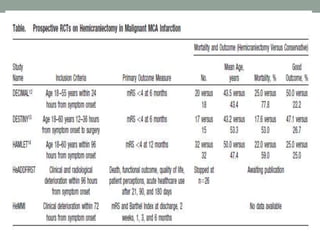

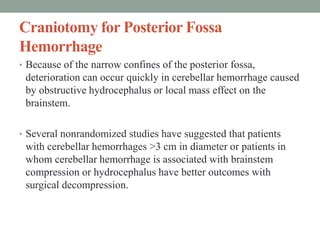

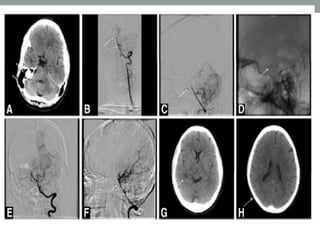

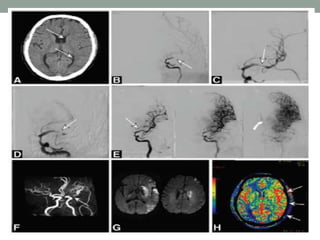

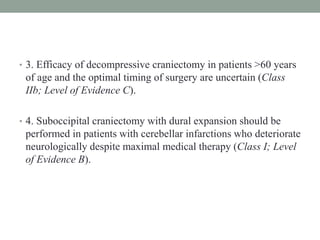

![• Three prospective, randomized trials studied patients with

supratentorial infarctions treated with decompressive

craniectomy, usually within 48 hours of stroke onset.

1. Decompressive Surgery for the Treatment of Malignant

Infarction of the Middle Cerebral Artery [DESTINY],

2. Decompressive Craniectomy in Malignant Middle Cerebral

Artery Infarction [DECIMAL], and

3. Hemicraniectomy After Middle Cerebral Artery Infarction

With Life-threatening Edema Trial [HAMLET])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/currentstatusofstrokeintervention-161123171521/85/Current-status-of-stroke-intervention-44-320.jpg)