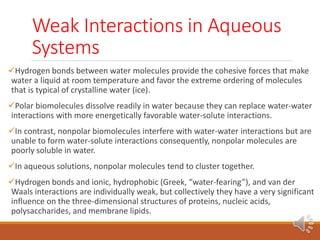

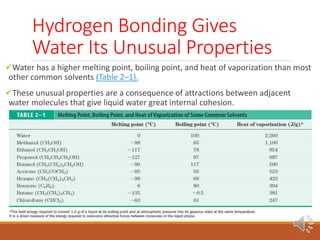

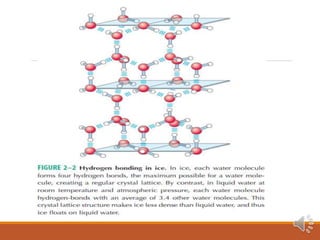

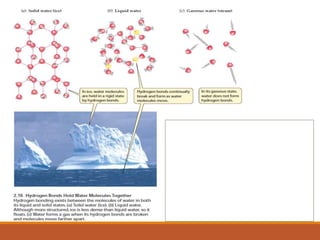

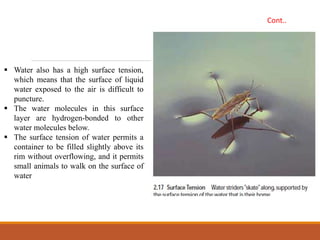

Water exists in three states and has unique properties due to its molecular structure and ability to form hydrogen bonds. As a polar molecule, water can form up to four hydrogen bonds with neighboring molecules, giving liquid water high cohesion and surface tension. This also accounts for water's unusually high melting and boiling points compared to similar compounds. The hydrogen bonding in ice locks molecules into a rigid crystalline structure that floats, allowing aquatic life to survive under frozen ponds and lakes.