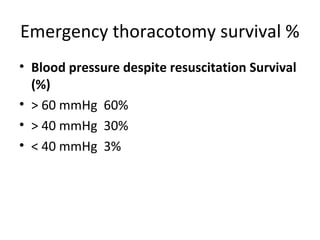

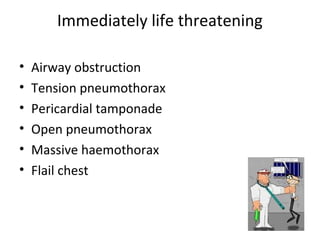

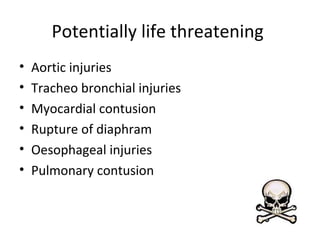

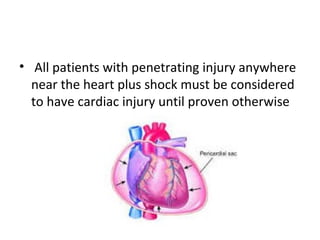

Thoracic injuries account for a significant portion of trauma deaths. The leading cause of death from thoracic injury is hemorrhage. Immediately life-threatening thoracic injuries include tension pneumothorax, massive hemothorax, flail chest, and pericardial tamponade. These injuries require rapid diagnosis and treatment to prevent further deterioration. While many thoracic injuries can be managed non-operatively with oxygen, analgesia, and chest tube drainage, emergency thoracotomy may be necessary to control severe hemorrhage in the chest from injuries to organs like the heart or lungs. Proper investigation and management of thoracic trauma can prevent avoidable deaths.

![treatment

• The correct immediate treatment of tamponade

is operative (sternotomy or left thoracotomy),

with repair of the heart in the operating theatre

if time allows or otherwise in the emergency

room.

• Pericardiocentesis has a high potential

foriatrogenic injury to the heart and it should at

the most beregarded as a desperate temporising

measure in a transport situation

• [under electrocardiogram (ECG) control].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thoracicinjury-140216054155-phpapp01/85/Thoracic-injury-26-320.jpg)