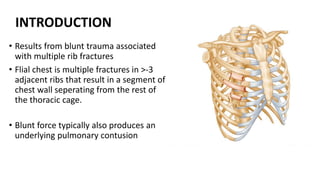

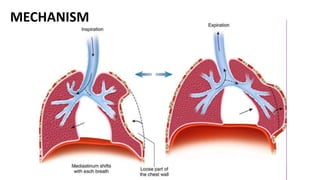

1) Rib fractures are common injuries from chest trauma and can lead to high morbidity and mortality, especially in elderly patients. Surgical fixation of rib fractures is increasingly being used to manage injuries.

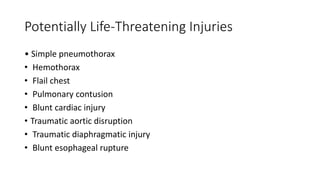

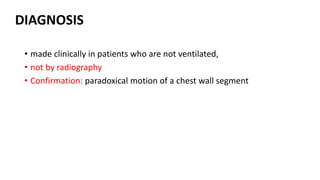

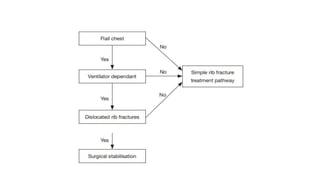

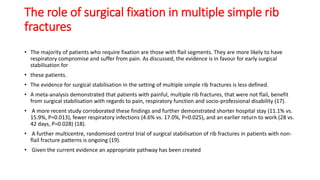

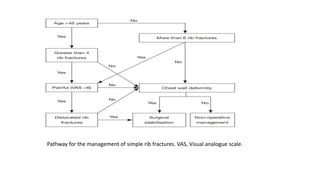

2) For flail chest segments, early surgical stabilization is recommended to reduce respiratory compromise and pain. For multiple simple rib fractures, surgical fixation may decrease pain and recovery time compared to conservative treatment.

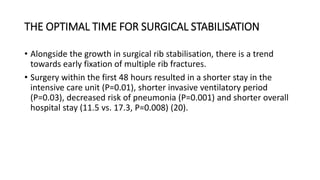

3) Early rib fixation within 72 hours of injury may lead to shorter hospital stays and fewer complications like pneumonia compared to later fixation. Surgical stabilization should generally be considered early for displaced or anterior chest wall fractures.