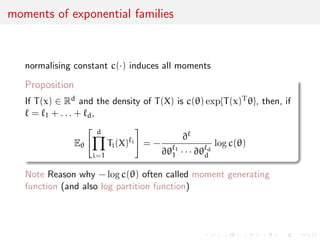

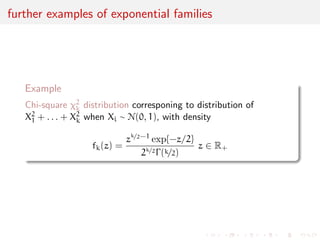

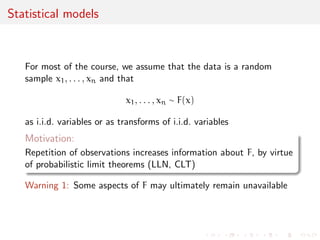

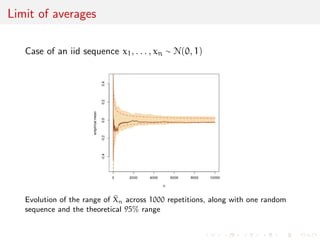

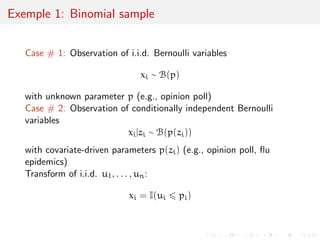

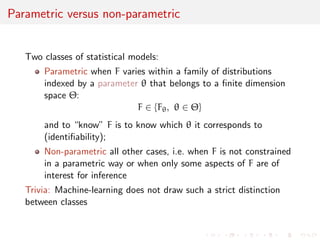

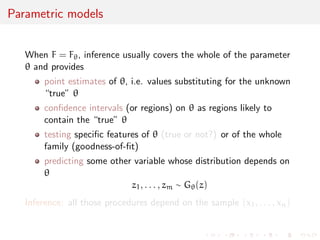

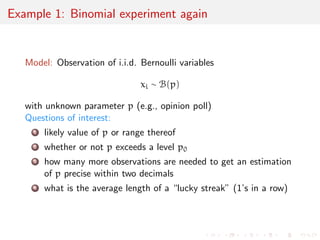

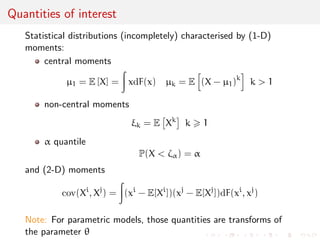

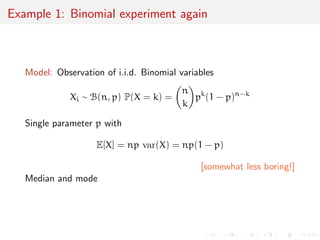

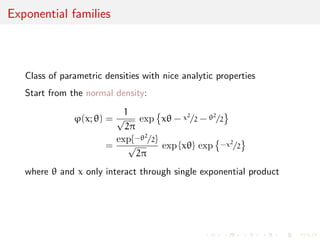

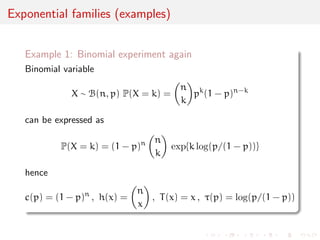

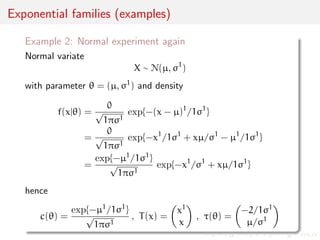

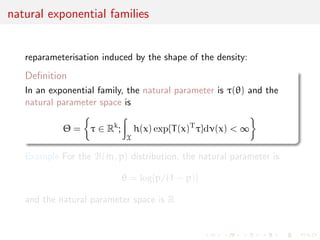

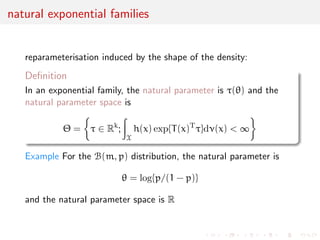

The document discusses statistical models and exponential families. It states that for most of the course, data is assumed to be a random sample from a distribution F. Repetition of observations via the law of large numbers and central limit theorem increases information about F. Exponential families are a class of parametric distributions with convenient analytic properties, where the density can be written as a function of natural parameters in an exponential form. Examples of exponential families include the binomial and normal distributions.

![ned

expectation E[X]

X1 + . . . + Xn

n

prob

! E[X]

[proof: see Terry Tao's What's new, 18 June 2008]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-7-320.jpg)

![ned

expectation E[X]

X1 + . . . + Xn

n

a.s.

! E[X]

[proof: see Terry Tao's What's new, 18 June 2008]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-9-320.jpg)

![ned

expectation E[X]

X1 + . . . + Xn

n

a.s.

! E[X]

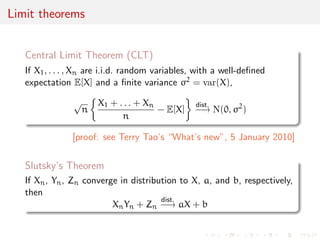

Central Limit Theorem (CLT)

If X1, . . . ,Xn are i.i.d. random variables, with a well-de](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-11-320.jpg)

![ned

expectation E[X] and a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-12-320.jpg)

![X1 + . . . + Xn

n

- E[X]

dist.

! N(0, 2)

[proof: see Terry Tao's What's new, 5 January 2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-14-320.jpg)

![ned

expectation E[X] and a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-16-320.jpg)

![X1 + . . . + Xn

n

- E[X]

dist.

! N(0, 2)

[proof: see Terry Tao's What's new, 5 January 2010]

Continuity Theorem

If

Xn

dist.

! a

and g is continuous at a, then

g(Xn)

dist.

! g(a)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-18-320.jpg)

![ned

expectation E[X] and a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-20-320.jpg)

![X1 + . . . + Xn

n

- E[X]

dist.

! N(0, 2)

[proof: see Terry Tao's What's new, 5 January 2010]

Slutsky's Theorem

If Xn, Yn, Zn converge in distribution to X, a, and b, respectively,

then

XnYn + Zn

dist.

! aX + b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-22-320.jpg)

![ned

expectation E[X] and a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-24-320.jpg)

![X1 + . . . + Xn

n

- E[X]

dist.

! N(0, 2)

[proof: see Terry Tao's What's new, 5 January 2010]

Delta method's Theorem

If p

nfXn - g

dist.

! Np(0,

)

and g : Rp ! Rq is a continuously dierentiable function on a

neighbourhood of 2 Rp, with a non-zero gradient rg(), then

p

n fg(Xn) - g()g

dist.

! Nq(0,rg()T

rg())](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-26-320.jpg)

![Non-parametric models

In non-parametric models, there may still be constraints on the

range of F`s as for instance

EF[YjX = x] = (](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/models-140923111143-phpapp02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-1-Models-35-320.jpg)