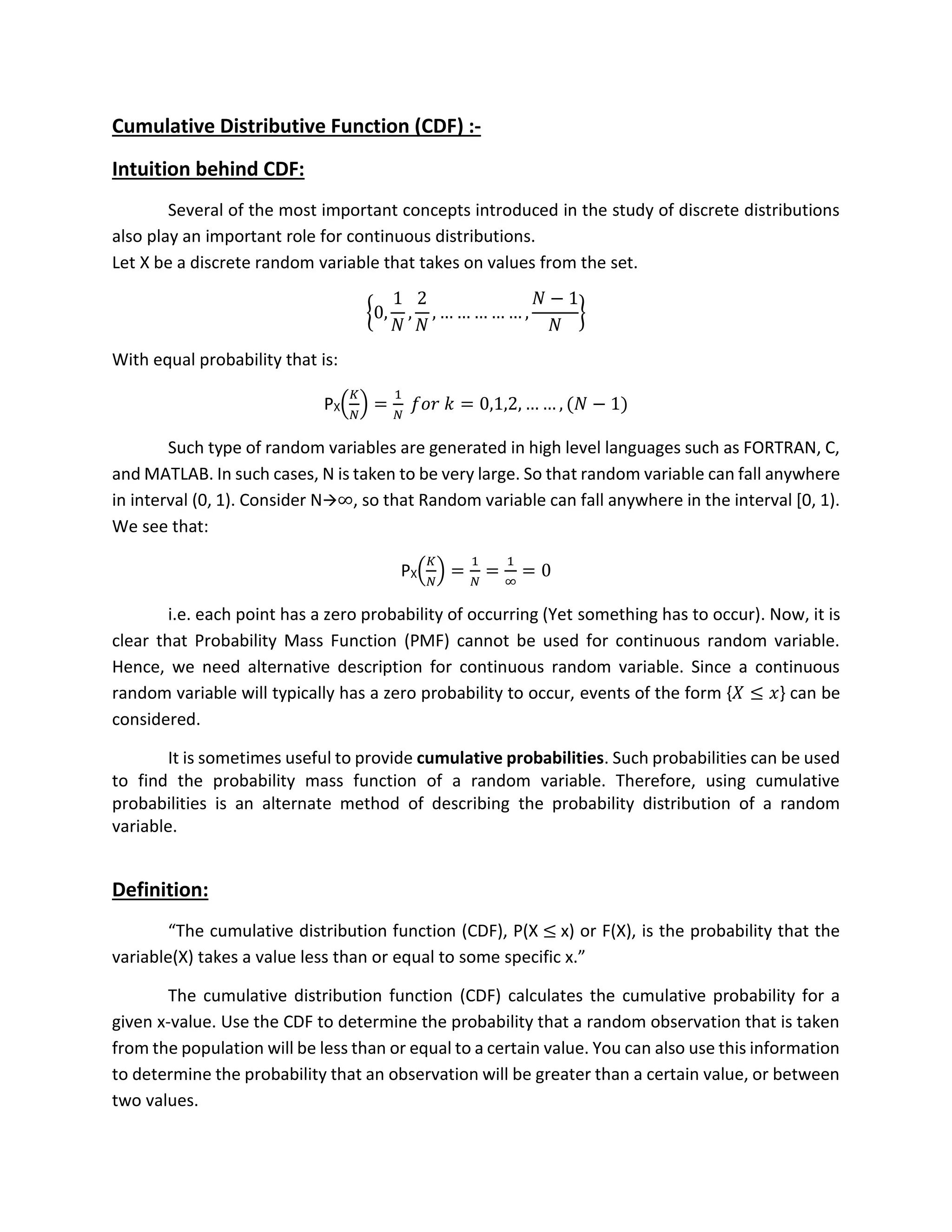

The document discusses cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) and probability density functions (PDFs) for continuous random variables. It provides definitions and properties of CDFs and PDFs. For CDFs, it describes how they give the probability that a random variable is less than or equal to a value. For PDFs, it explains how they provide the probability of a random variable taking on a particular value. The document also gives examples of CDFs and PDFs for exponential and uniform random variables.

![Exponential random variable:

The cumulative distribution function is given by

Proof:

For x ≥ 0:

FX(x) = Pr{X ≤ 𝑥} = fX(y) dy

FX(x) = ∫

1

𝑏

𝑥

−∞

exp (−

𝑥

𝑏

) u(y) dy

FX(x) = ∫

1

𝑏

𝑥

0

e-(y/b) dy

FX(x) =

1

𝑏

[(e-(y/b))/(-1/b)]0

𝑥

FX(x) = -e-(y/b)

FX(x) = 1 – exp(−

𝑥

𝑏

) ux

For x < 0:

FX(x) = 0

Properties:

1)

a. FX(−∞) = Pr{ X ≤ −∞ } = 0

b. FX(+∞) = Pr{ X ≤ +∞ } = 1

Proof:

By definition, FX (a) = P(A) where A = {X ≤ a}. Then F(= +∞) = P(A), with A = {X ≤ +∞}. This

event is the certain event, since A = {X ≤ +∞} = {X ∈ R} = S (S for Sample Space). Therefore

F(= +∞) = P(S) = 1. Similarly, Then F(= −∞) = P(A), with A = {X ≤ −∞}. This event is the

impossible event, random variable X is a real variable, so F(= −∞) = P(∅) = 0.

2) Since CDF is a probability so it must take on values between ‘0’ and ‘1’.

0 ≤ FX(x) ≤ 1

∫

∞

−∞](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-180628185704/75/Probability-and-Statistics-3-2048.jpg)

![Proof:

As minimum FX(−∞) = Pr{ X ≤ −∞ } = 0 and maximum FX(+∞) = Pr{ X ≤ +∞ } = 1. So

FX(x) should be lie between [0, 1].

3) For fixed x1 and x2 if x1 ≤ x2 then FX(x1) ≤ FX(x2).

Consider tub events {X ≤ x1} and {X ≤ x2}, then the former is the subset of the later. (i.e. if the

former event occurs, we must be in the later as well.)

If x1 < x2 then FX(x) = Pr{X ≤ 𝑥}

This implies that CDF is a Monotonic Non-Decreasing Function. (It will never decrease in

any case.)

Proof:

This is a consequence of the fact that probability is a non-decreasing function, i.e. if

A ⊆ B then P(A) ≤ P(B). Indeed, recall that if A ⊆ B then the set B can be partitioned into

B = A + (B ∩ A), so, using the additivity property of probability, P(B) = P(A) + P(B ∩ A) ≥ P(A).

If x1 ≤ x2, then the corresponding events A = {X ≤ x1} and B = {X ≤ x2} have the property that

A ⊂ B. Therefore P{X ≤ x1} _ P{X ≤ x2}, which by the definition of a CDF means F(x1) ≤ F(x2).

4) For x1 < x2

Pr{x1 < X ≤ 𝑥2} = FX(x2) - FX(x1)

Proof:

Consider {X ≤ 𝑥2}, we can break it into two mutually exclusive events.

(−∞, 𝑥2] = (−∞, 𝑥1] ∪ (𝑥1, 𝑥2]

Pr{X ≤ 𝑥2} = {X ≤ 𝑥1} ∪ {x1 < X ≤ 𝑥2}

Pr{X ≤ 𝑥2} = Pr{X ≤ 𝑥1} + Pr{x1 < X ≤ 𝑥2}

FX(x2) = FX(x1) + Pr{x1 < X ≤ 𝑥2}

Pr{x1 < X ≤ 𝑥2} = FX(x2) - FX(x1)

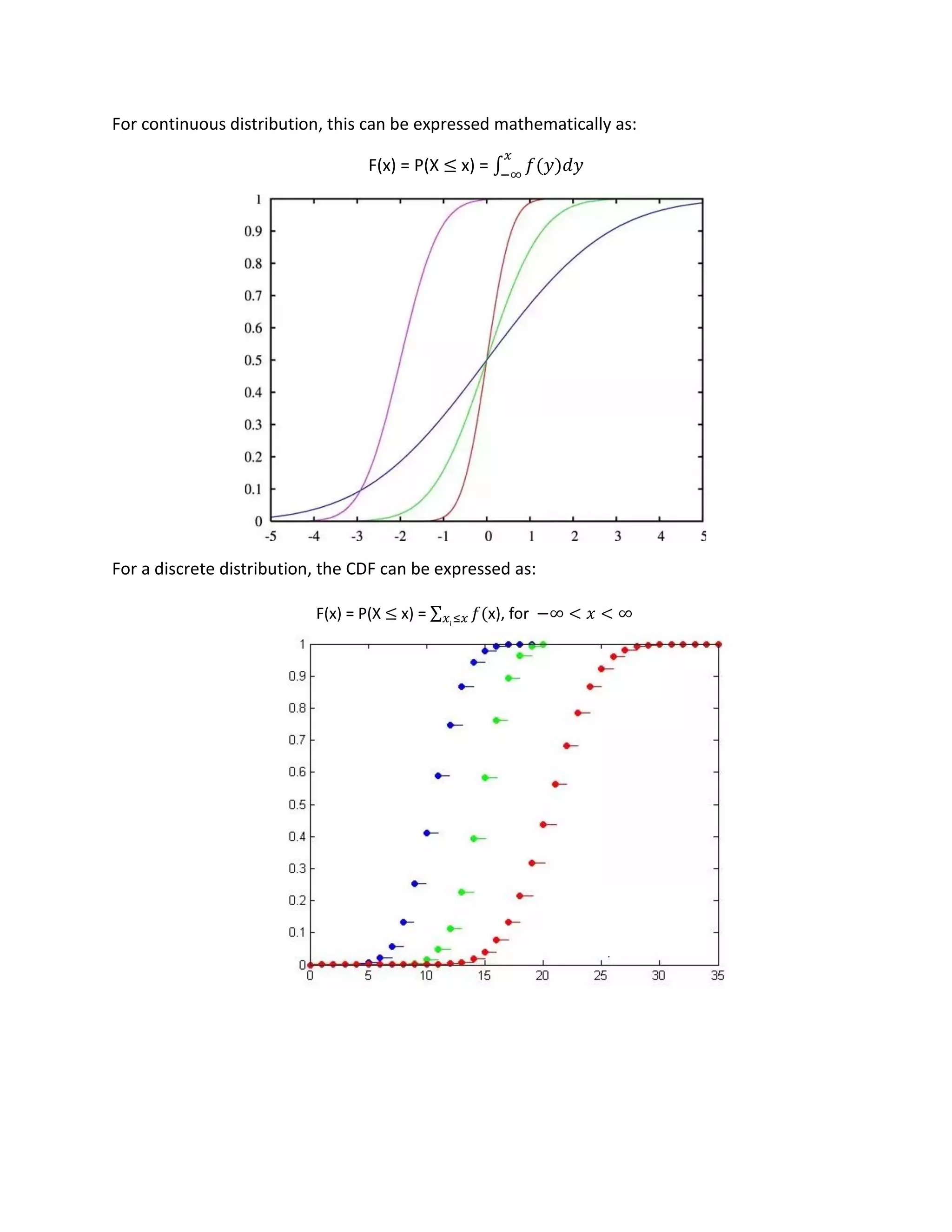

Note:

If x<0 then FX(x) = 0

If x ≥

𝑁−1

𝑁

then FX(x) = 1

If 0 < k < N ∀ 𝑥 ∈ [

𝑘−1

𝑁

,

𝑘

𝑁

) FX(x) =

𝑘

𝑁](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-180628185704/75/Probability-and-Statistics-4-2048.jpg)

![For exponential random variable:

An exponential random variable has a PDF of the form

fX(x) =

where 𝜆 is a positive parameter characterizing the PDF. This is a legitimate PDF because

fx(x) dx = 𝜆𝑒 dx = −𝑒 0

∞

= 1

Properties of PDF:

1) fx(x) ≥ 0 for all values of x since F is non-decreasing.

2) fx(x) =

𝑑

𝑑𝑥

FX(x)

3) FX(x) = Pr{X ≤ 𝑥} = fx(y) dy

4) fx(x) dx = 1

5) fX(x) = Pr(𝑎 ≤ 𝑋 ≤ 𝑏)

6) lim

𝑥→−∞

𝑓(𝑥) = 0 = lim

𝑥→∞

𝑓(𝑥)

7) *In the continuous case P(X = c) = 0 for every possible value of c.

8) *This has a very useful consequence in the continuous case:

Pr (a ≤ X ≤ b) = Pr (a < X ≤ b) = Pr (a ≤ X < b) = Pr (a < X < b)

Continuous Random Variable:

A continuous random variable is a random variable with an interval (either finite or

infinite) of real numbers for its range.

Random variables that can assume any one of the uncountable infinite numbers of

points in one or more intervals on the real line are called continuous random variables. If a

random variable X assumes every possible value in an interval [a, b] or (−∞,+∞) is called

continuous random variable.

A continuous distribution describes the probabilities of the possible values of a

continuous random variable. A continuous random variable is a random variable with a set of

possible values (known as the range) that is infinite and uncountable.

Probabilities of continuous random variables (X) are defined as the area under the curve

of its PDF. Thus, only ranges of values can have a nonzero probability. The probability that a

continuous random variable equals some value is always zero.

∫

𝑥

−∞

∫

∞

−∞

∫

𝑏

𝑎

𝜆𝑒 if x ≥ 0−𝜆𝑥

0 otherwise

∫

∞

−∞

−𝜆𝑥 −𝜆𝑥

∫

∞

0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-180628185704/75/Probability-and-Statistics-8-2048.jpg)

![Definition:

The nth moment of a random variable X is define as:

E(xn) = xn fX(x) dx

E(xn) = xk

n PX (xk)

E(x2) = x2 fX(x) dx

𝛾 =

(𝑥 − 𝑥̅)

𝑥 − 1

𝛾 = √

(𝑥 − 𝑥̅)

𝑥 − 1

𝛾2 = E [(x - 𝜇x)2]

𝛾2 = E [(x2 + 𝜇x2 – 2x 𝜇x]

𝛾2 = E (x2) + 𝜇x2 – 2E(x) 𝜇x

𝛾2 = E (x2) + 𝜇x2 – 2𝜇x 𝜇x

𝛾2 = E (x2) + 𝜇x2 – 2𝜇x2

𝛾2 = E (x2) - 𝜇x2

Gaussian Random Variables:

One of the most important random variable since many physical phenomena can be

modeled as Gaussian random variable e.g. thermal noise in electronic components, students

grading etc. It is named after the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss.

The PDF is:

fX(x) =

1

√2𝜋𝛿

𝑒

Its PDF has two parameters:

Mean = m

𝛿 = Standard Derivation

𝛿2 = Variance

Gaussian functions are often used to represent the probability density function of a normally

distributed random variable.

Shortened Notation:

X ~ N (m, 𝛾2)

∫

∞

−∞

∑

𝑘

∫

∞

−∞

2

2

2

i

2

−

(𝑥 − 𝑚)

2𝛿

2

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-180628185704/75/Probability-and-Statistics-11-2048.jpg)

![Expected value of function of random variable:

The concept of expectation can be applied to function of random variables as well. If X is

continuous, then the expectation of g(X) is defined as,

E[g(x)] = ∫ 𝑔(𝑥)

∞

−∞

fX(x) dx (Continuous Random Variable)

where f is the probability density function of X.

If X is discrete, then the expectation of g(X) is defined as, then,

E[g(x)) = 𝑔𝑘 (xk)PX(k) (Discrete Random Variable)

where f is the probability mass function of X and X is the support of X.

If E(X) = −∞ or E(X) = ∞ (i.e., E(|X|) = ∞), then we say the expectation E(X) does not

exist. The expectation operator has inherits its properties from those of summation and

integral.

For example if X is original Random variable, you might be interested in what happen to

the mean if you scale by

Y = cx

Normal Random Variables:

We say that X is a normal random variable, or simply that is normally distributed,

with parameters 𝜇 and 𝛿2. If the density of X is given by:

The normal random variables was introduced by the French mathematician

Abraham de Moivre in 1733, who used it to approximate associated with binomial

random variables when the binomial parameter n is large. The result was later extended

by Laplace and other and is now encompassed in a probability theorem known as the

central limit theorem. The central limit theorem, one of the two most important result in

the probability theory gives a theoretical base to the often noted empirical observation

that, in practice, in example many random phenomena abbey, at least approximately, a

normal probability distribution. Some example of random phenomena obeying this

behavior are the height of a man, the velocity in any direction of a molecule in gas, and

the error made in the measuring a physical quantity.

An important implication of the preceding result is that if X is normally distributed

with parameters 𝜇 and 𝛿2, then

𝑍 =

(𝑥 − 𝜇)

𝛿

is normally distributed with parameters 0 and 1. Such a random variable is said to be a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-180628185704/75/Probability-and-Statistics-13-2048.jpg)

![per game will be:

𝑥𝑛

𝑖=1 i P(xi) = E[X]

The probability concept of expectation is analogous to the physical concept of

center of gravity of distribution of mass.

Exponential random variable:

In probability theory and statistics, the exponential distribution (also known as negative

exponential distribution) is the probability distribution that describes the time between events

in a Poisson point process, i.e., a process in which events occur continuously and independently

at a constant average rate. It is a particular case of the gamma distribution. It is the continuous

analogue of the geometric distribution, and it has the key property of being memoryless. In

addition to being used for the analysis of Poisson point processes it is found in various other

contexts.

The exponential distribution is not the same as the class of exponential families of

distributions, which is a large class of probability distributions that includes the exponential

distribution as one of its members, but also includes the normal distribution, binomial

distribution, gamma distribution, Poisson, and many others.

Exponential random variable can be defined as:

fX(x) =

1

𝑏

exp (−

𝑥

𝑏

) u(x)

E(x) = ∫ 𝑥

∞

−∞

fX(x) dx

E(x) = ∫ 𝑥

∞

−∞

1

𝑏

exp (−

𝑥

𝑏

) u(x) dx

E(x) = ∫ 𝑥

∞

0

1

𝑏

e (-x/b) d(x)

Let y=

𝑥

𝑏

limits: y =

0

𝑏

= 0; y =

∞

𝑏

= ∞

dy =

1

𝑏

dx dx = b dy

E(x) = b ∫ 𝑦

∞

0

e-y dy

Integration by parts:

E(x) = b [y (e-y/-1) – ∫(𝑒-y/-1) dy]0

∞

E(x) = b [-y e-y + ∫ 𝑒-y dy]0

∞](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-180628185704/75/Probability-and-Statistics-15-2048.jpg)

![E(x) = b [-y e-y - e-y ]0

∞

∎ lim

𝑦→∞

𝑒-y = 0

E(x) = b[0 – (0-1)]

E(x) = b

The exponential distribution often arises as the distribution of the amount of time

until some specific event occurs. For instance, the amount of time until an earth quake

occurs, or until a new war breaks out, or until a telephone call you receive turns out to be

a wrong number are all random variables that tend in practice to have exponential

distributions.

An exponential random variable can be a very good model for the amount of time

until a piece of equipment breaks down, until a light bulb burns out, or until an accident

occur.

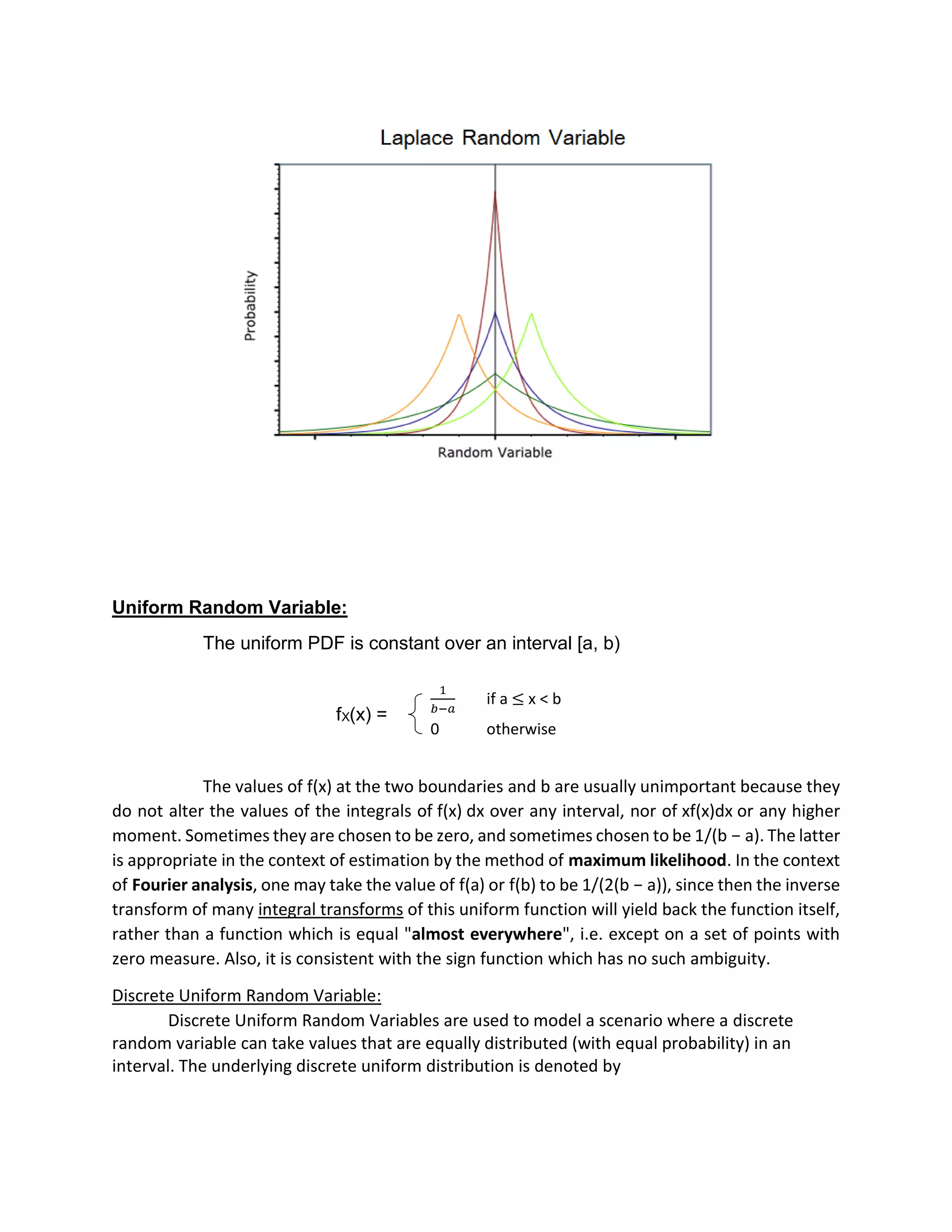

Laplacian Random Variable:

In probability theory and statistics, the Laplace distribution is a continuous probability

distribution named after Pierre-Simon Laplace. It is also sometimes called the double

exponential distribution, because it can be thought of as two exponential distributions (with an

additional location parameter) spliced together back-to-back, although the term is also

sometimes used to refer to the Gumbel distribution. The difference between two independent

identically distributed exponential random variables is governed by a Laplace distribution, as is

a Brownian motion evaluated at an exponentially distributed random time. Increments

of Laplace motion or a variance gamma process evaluated over the time scale also have a Laplace

distribution.

FX(x) =

1

2𝑏

exp (−

|𝑥|

𝑏

)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-180628185704/75/Probability-and-Statistics-16-2048.jpg)