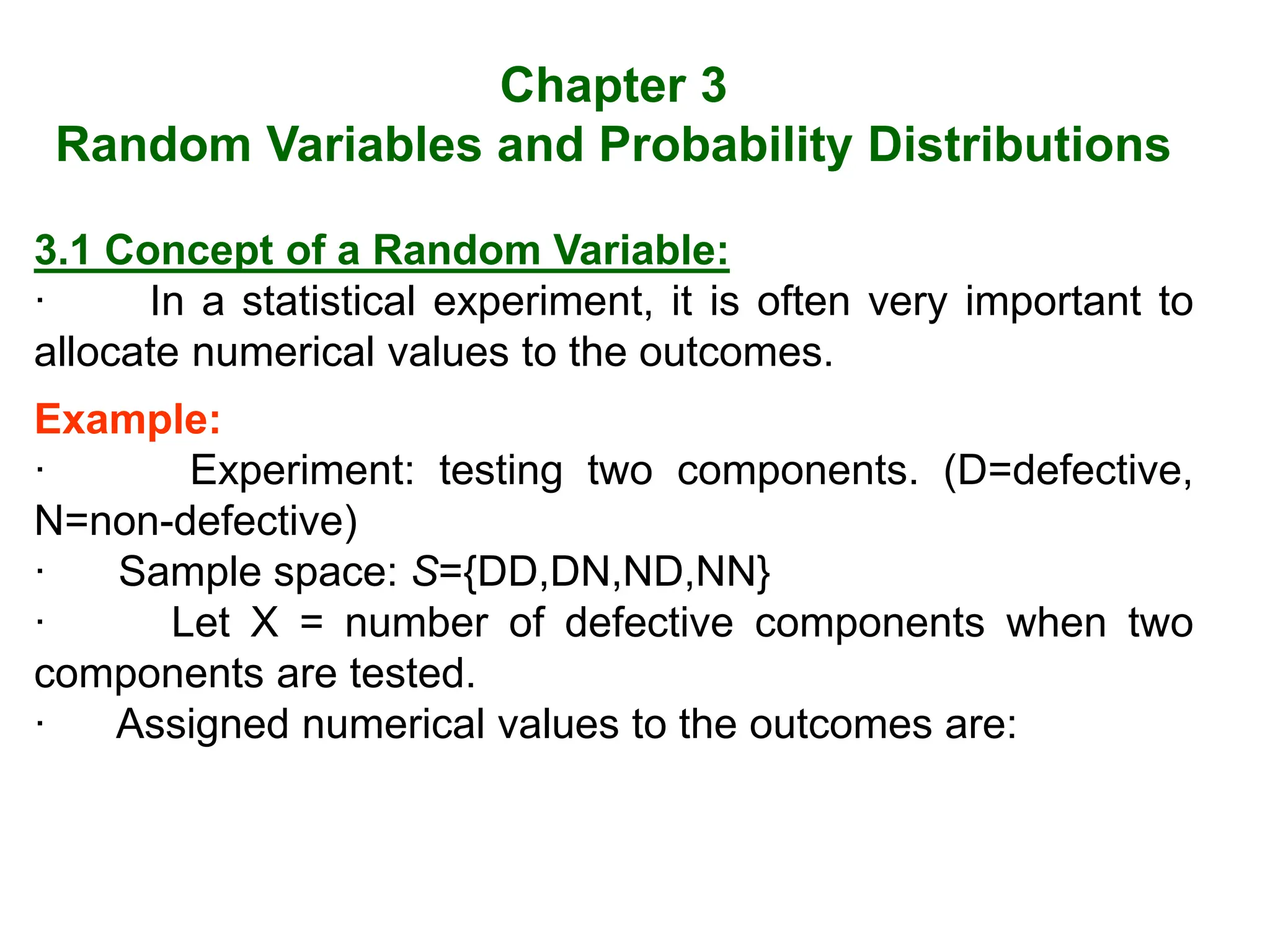

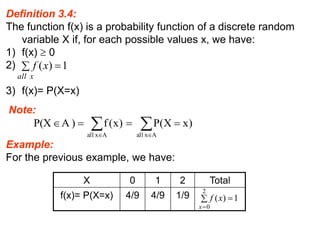

The document summarizes key concepts about random variables and probability distributions. It defines a random variable as a function that assigns numerical values to outcomes of a statistical experiment. Random variables can be discrete, taking on countable values, or continuous, having values on a continuous scale.

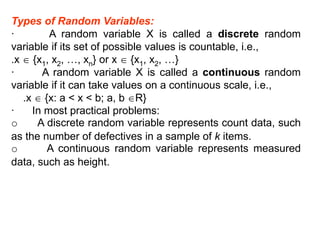

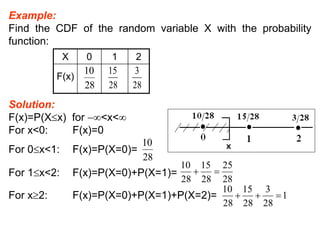

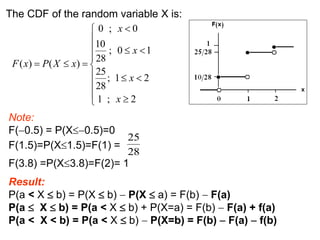

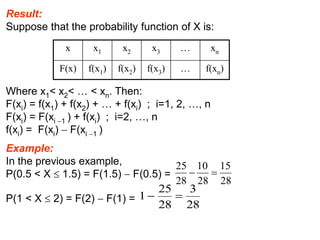

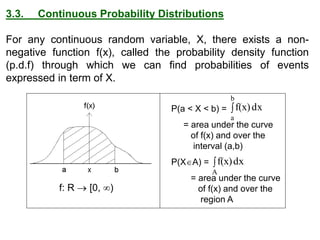

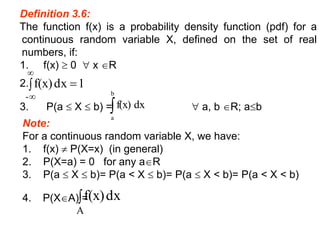

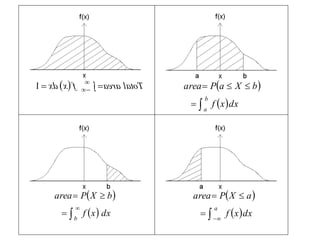

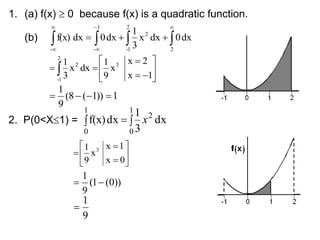

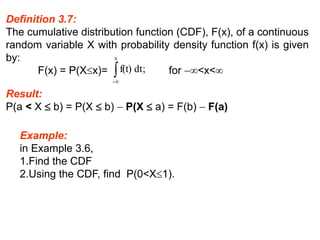

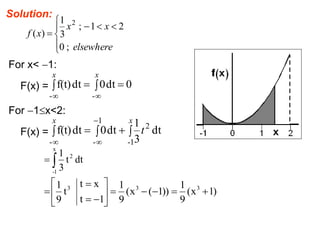

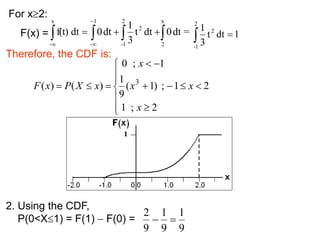

For discrete random variables, the probabilities of each value are specified by the probability mass function (PMF). For continuous random variables, the probability density function (PDF) gives the probability of values in an interval as the area under the curve of the function. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) gives the probability that a random variable is less than or equal to a value.

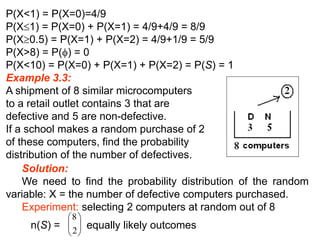

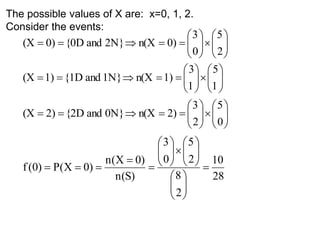

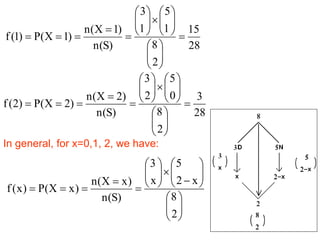

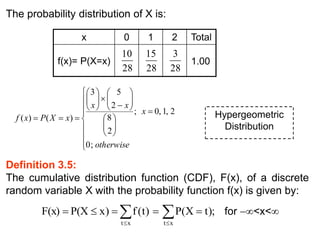

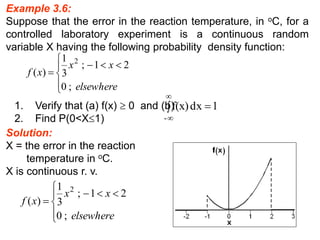

An example calculates the PMF of the number of defective computers selected in