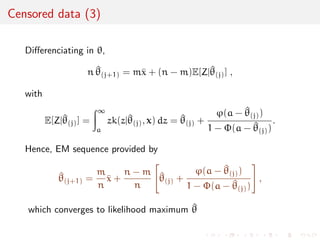

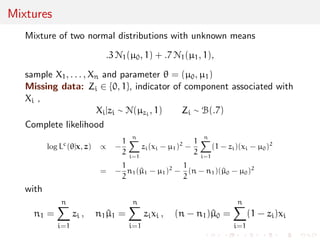

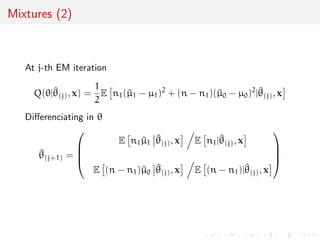

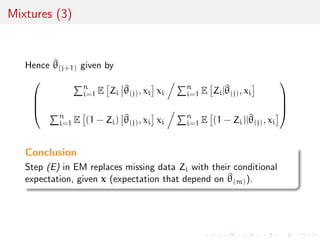

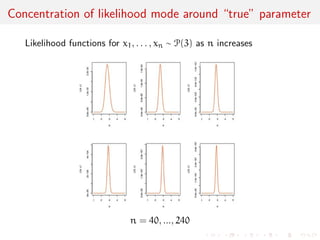

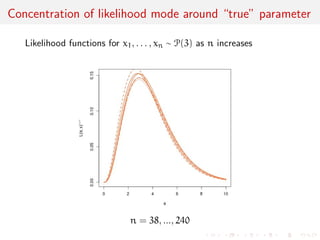

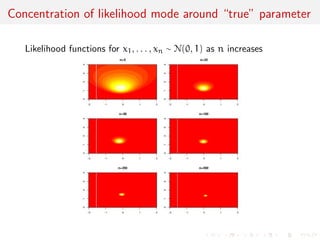

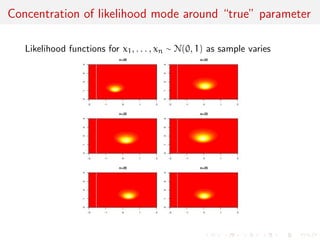

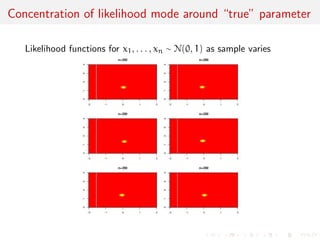

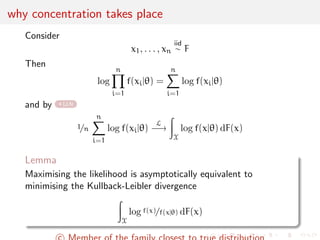

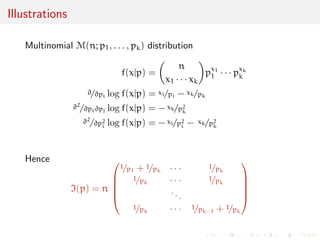

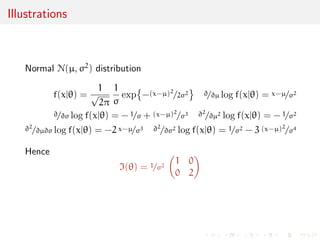

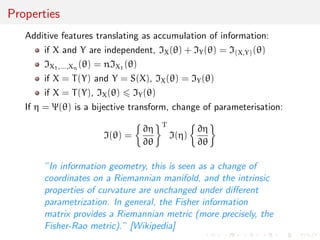

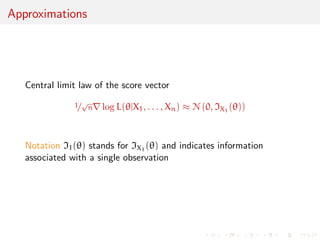

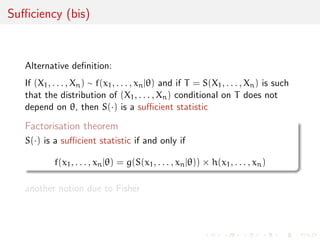

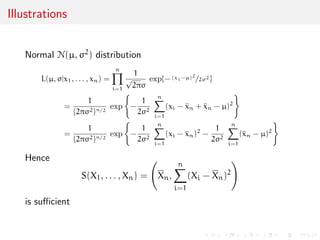

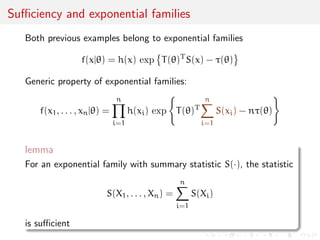

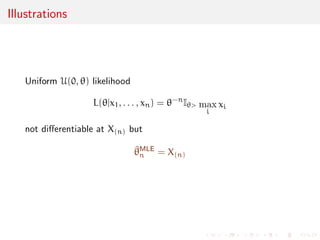

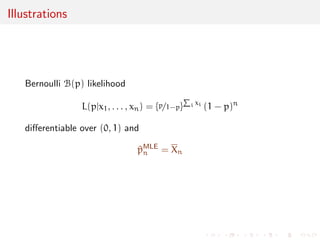

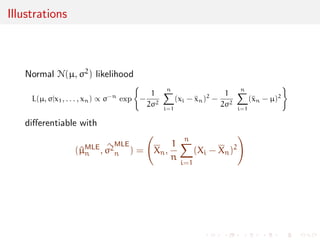

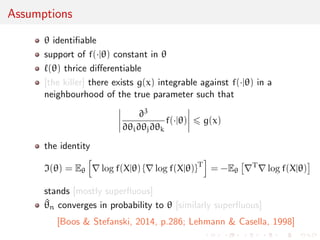

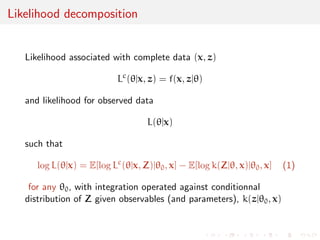

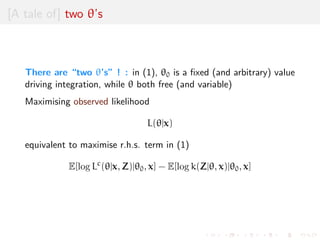

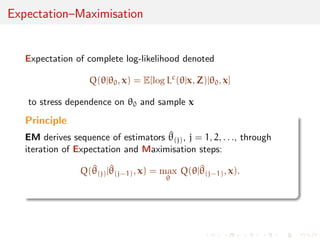

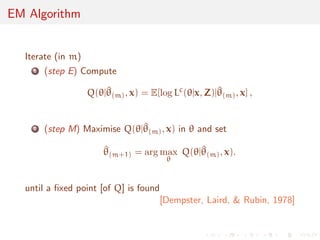

The document discusses likelihood functions and inference. It begins by defining the likelihood function as the function that gives the probability of observing a sample given a parameter value. The likelihood varies with the parameter, while the density function varies with the data. Maximum likelihood estimation chooses parameters that maximize the likelihood function. The score function is the gradient of the log-likelihood and has an expected value of zero at the true parameter value. The Fisher information matrix measures the curvature of the likelihood surface and provides information about the precision of parameter estimates. It relates to the concentration of likelihood functions around the true parameter value as sample size increases.

![Chapter 3 :

Likelihood function and inference

[0]

4 Likelihood function and inference

The likelihood

Information and curvature

Suciency and ancilarity

Maximum likelihood estimation

Non-regular models

EM algorithm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/75/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-1-2048.jpg)

![xed measure ], the density of the iid

sample x1, . . . , xn is

Yn

i=1

f(xi)

Note In the special case is a counting measure,

Yn

i=1

f(xi)

is the probability of observing the sample x1, . . . , xn among all

possible realisations of X1, . . . ,Xn](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-3-320.jpg)

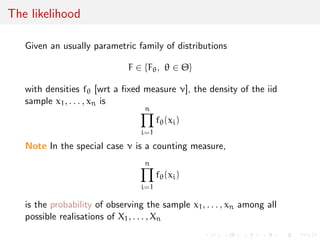

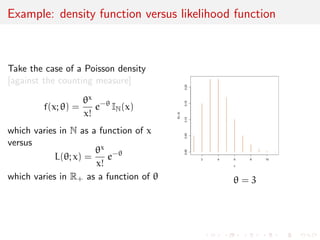

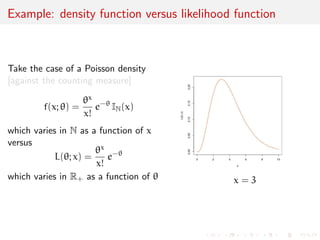

![Example: density function versus likelihood function

Take the case of a Poisson density

[against the counting measure]

f(x; ) =

x

x!

e- IN(x)

which varies in N as a function of x

versus

L(; x) =

x

x!

e-

which varies in R+ as a function of = 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-6-320.jpg)

![Example: density function versus likelihood function

Take the case of a Poisson density

[against the counting measure]

f(x; ) =

x

x!

e- IN(x)

which varies in N as a function of x

versus

L(; x) =

x

x!

e-

which varies in R+ as a function of x = 3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-7-320.jpg)

![Example: density function versus likelihood function

Take the case of a Normal N(0, )

density [against the Lebesgue measure]

f(x; ) =

1

p

2

e-x2=2 IR(x)

which varies in R as a function of x

versus

L(; x) =

1

p

2

e-x2=2

which varies in R+ as a function of

= 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-8-320.jpg)

![Example: density function versus likelihood function

Take the case of a Normal N(0, )

density [against the Lebesgue measure]

f(x; ) =

1

p

2

e-x2=2 IR(x)

which varies in R as a function of x

versus

L(; x) =

1

p

2

e-x2=2

which varies in R+ as a function of

x = 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-9-320.jpg)

![Example: density function versus likelihood function

Take the case of a Normal N(0, 1=)

density [against the Lebesgue measure]

f(x; ) =

p

p

2

e-x2=2 IR(x)

which varies in R as a function of x

versus

L(; x) =

p

p

2

e-x2=2 IR(x)

which varies in R+ as a function of

= 1=2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-10-320.jpg)

![Example: density function versus likelihood function

Take the case of a Normal N(0, 1=)

density [against the Lebesgue measure]

f(x; ) =

p

p

2

e-x2=2 IR(x)

which varies in R as a function of x

versus

L(; x) =

p

p

2

e-x2=2 IR(x)

which varies in R+ as a function of

x = 1=2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-11-320.jpg)

![Example: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

Population genetics:

Genotypes of biallelic genes AA, Aa, and aa

sample frequencies nAA, nAa and naa

multinomial model M(n; pAA, pAa, paa)

related to population proportion of A alleles, pA:

pAA = p2

A , pAa = 2pA(1 - pA) , paa = (1 - pA)2

likelihood

L(pAjnAA, nAa, naa) / p2nAA

A [2pA(1 - pA)]nAa(1 - pA)2naa

[Boos Stefanski, 2013]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-12-320.jpg)

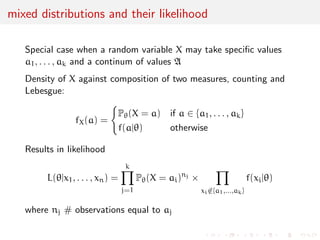

![c values

a1, . . . , ak and a continum of values A

Example: Rainfall at a given spot on a given day may be zero with

positive probability p0 [it did not rain!] or an arbitrary number

between 0 and 100 [capacity of measurement container] or 100

with positive probability p100 [container full]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-14-320.jpg)

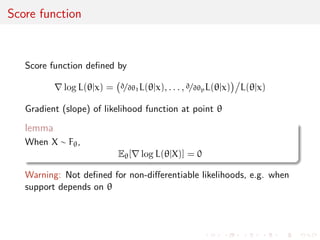

![ned by

rlog L(jx) =

@=@1L(jx), . . . , @=@pL(jx)

L(jx)

Gradient (slope) of likelihood function at point

lemma

When X F,

E[rlog L(jX)] = 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-28-320.jpg)

![ned by

rlog L(jx) =

@=@1L(jx), . . . , @=@pL(jx)

L(jx)

Gradient (slope) of likelihood function at point

lemma

When X F,

E[rlog L(jX)] = 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-30-320.jpg)

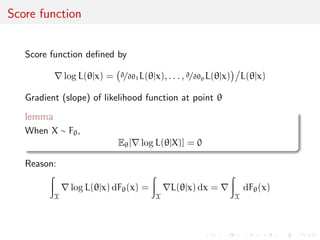

![ned by

rlog L(jx) =

@=@1L(jx), . . . , @=@pL(jx)

L(jx)

Gradient (slope) of likelihood function at point

lemma

When X F,

E[rlog L(jX)] = 0

Reason:

Z

X

rlog L(jx) dF(x) =

Z

X

rL(jx) dx = r

Z

X

dF(x)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-32-320.jpg)

![ned by

rlog L(jx) =

@=@1L(jx), . . . , @=@pL(jx)

L(jx)

Gradient (slope) of likelihood function at point

lemma

When X F,

E[rlog L(jX)] = 0

Connected with concentration theorem: gradient null on average

for true value of parameter](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-34-320.jpg)

![ned by

rlog L(jx) =

@=@1L(jx), . . . , @=@pL(jx)

L(jx)

Gradient (slope) of likelihood function at point

lemma

When X F,

E[rlog L(jX)] = 0

Warning: Not de](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-36-320.jpg)

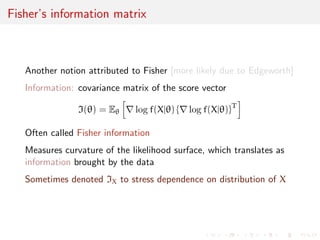

![Fisher's information matrix

Another notion attributed to Fisher [more likely due to Edgeworth]

Information: covariance matrix of the score vector

I() = E

h

rlog f(Xj) frlog f(Xj)gT

i

Often called Fisher information

Measures curvature of the likelihood surface, which translates as

information brought by the data

Sometimes denoted IX to stress dependence on distribution of X](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-38-320.jpg)

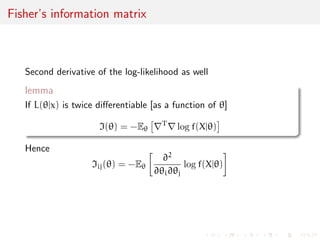

![Fisher's information matrix

Second derivative of the log-likelihood as well

lemma

If L(jx) is twice dierentiable [as a function of ]

I() = -E

rTrlog f(Xj)

Hence

Iij() = -E

@2

@i@j

log f(Xj)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-39-320.jpg)

![@

@

In information geometry, this is seen as a change of

coordinates on a Riemannian manifold, and the intrinsic

properties of curvature are unchanged under dierent

parametrization. In general, the Fisher information

matrix provides a Riemannian metric (more precisely, the

Fisher-Rao metric). [Wikipedia]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-46-320.jpg)

![@

@

In information geometry, this is seen as a change of

coordinates on a Riemannian manifold, and the intrinsic

properties of curvature are unchanged under dierent

parametrization. In general, the Fisher information

matrix provides a Riemannian metric (more precisely, the

Fisher-Rao metric). [Wikipedia]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-49-320.jpg)

![Approximations

Back to the Kullback{Leibler divergence

D(0, ) =

Z

X

f(xj0) log f(xj0)=f(xj) dx

Using a second degree Taylor expansion

log f(xj) = log f(xj0) + ( - 0)Trlog f(xj0)

+

1

2

( - 0)TrrT log f(xj0)( - 0) + o(jj - 0 jj2)

approximation of divergence:

D(0, )

1

2

( - 0)TI(0)( - 0)

[Exercise: show this is exact in the normal case]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-50-320.jpg)

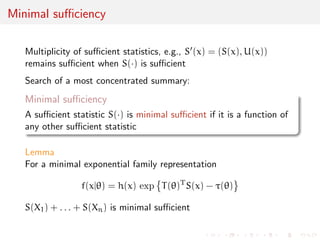

![Suciency

What if a transform of the sample

S(X1, . . . ,Xn)

contains all the information, i.e.

I(X1,...,Xn)() = IS(X1,...,Xn)()

uniformly in ?

In this case S() is called a sucient statistic [because it is

sucient to know the value of S(x1, . . . , xn) to get complete

information]

A statistic is an arbitrary transform of the data X1, . . . ,Xn](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-52-320.jpg)

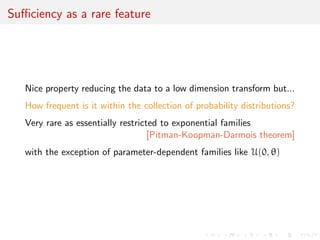

![Suciency as a rare feature

Nice property reducing the data to a low dimension transform but...

How frequent is it within the collection of probability distributions?

Very rare as essentially restricted to exponential families

[Pitman-Koopman-Darmois theorem]

with the exception of parameter-dependent families like U(0, )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-59-320.jpg)

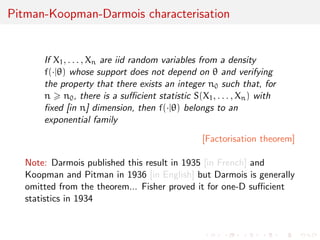

![xed [in n] dimension, then f(j) belongs to an

exponential family

[Factorisation theorem]

Note: Darmois published this result in 1935 [in French] and

Koopman and Pitman in 1936 [in English] but Darmois is generally

omitted from the theorem... Fisher proved it for one-D sucient

statistics in 1934](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-61-320.jpg)

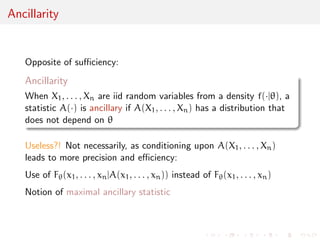

![Illustrations

1 If X1, . . . ,Xn

iid

U(0, ), A(X1, . . . ,Xn) = (X1, . . . ,Xn)=X(n)

is ancillary

2 If X1, . . . ,Xn

iid

N(, 2),

A(X1, . . . ,Xn) =

(X1P- Xn, . . . ,Xn - Xn n

i=1(Xi - Xn)2

is ancillary

3 If X1, . . . ,Xn

iid

f(xj), rank(X1, . . . ,Xn) is ancillary

x=rnorm(10)

rank(x)

[1] 7 4 1 5 2 6 8 9 10 3

[see, e.g., rank tests]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-64-320.jpg)

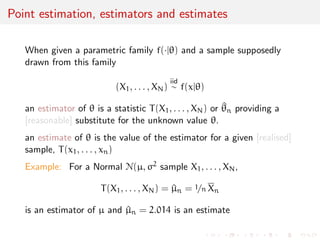

![Point estimation, estimators and estimates

When given a parametric family f(j) and a sample supposedly

drawn from this family

(X1, . . . ,XN)

iid

f(xj)

an estimator of is a statistic T(X1, . . . ,XN) or ^n providing a

[reasonable] substitute for the unknown value .

an estimate of is the value of the estimator for a given [realised]

sample, T(x1, . . . , xn)

Example: For a Normal N(, 2 sample X1, . . . ,XN,

T(X1, . . . ,XN) = ^n = 1=n Xn

is an estimator of and ^n = 2.014 is an estimate](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-65-320.jpg)

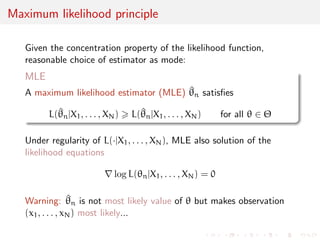

![Maximum likelihood invariance

Principle independent of parameterisation:

If = h() is a one-to-one transform of , then

^

MLE

n = h(^MLE

n )

[estimator of transform = transform of estimator]

By extension, if = h() is any transform of , then

^

MLE

n = h(^MLE

n )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-68-320.jpg)

![nity of MLE's [or of solutions to likelihood

equations]

3

1

2 Case of x1, . . . , xn N(1 + 2, 1) [[and mixtures of normal]

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-71-320.jpg)

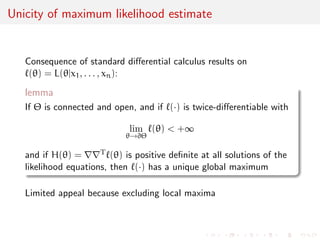

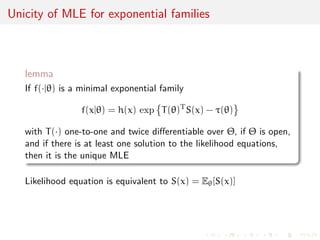

![Unicity of MLE for exponential families

lemma

If f(j) is a minimal exponential family

f(xj) = h(x) exp

T()TS(x) - ()

with T() one-to-one and twice dierentiable over , if is open,

and if there is at least one solution to the likelihood equations,

then it is the unique MLE

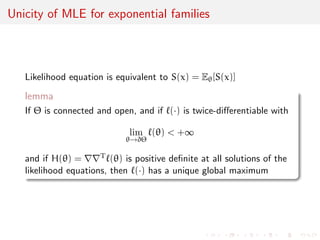

Likelihood equation is equivalent to S(x) = E[S(x)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-75-320.jpg)

![Unicity of MLE for exponential families

Likelihood equation is equivalent to S(x) = E[S(x)]

lemma

If is connected and open, and if `() is twice-dierentiable with

lim

!@

`() +1

and if H() = rrT`() is positive de](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/like-141026114245-conversion-gate02/85/Statistics-1-estimation-Chapter-3-likelihood-function-and-likelihood-estimation-76-320.jpg)