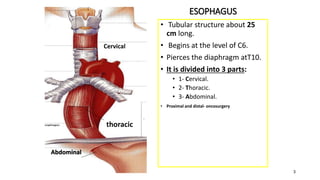

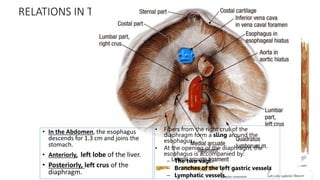

1. The esophagus is approximately 25 cm long and passes through the neck, chest and abdomen before connecting to the stomach.

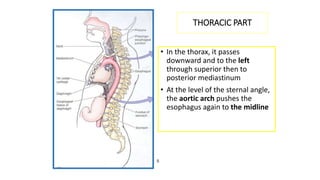

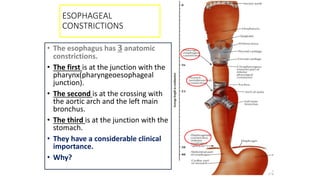

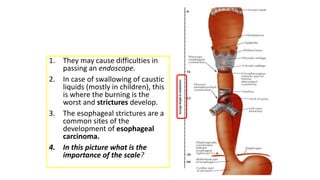

2. It has three parts - cervical, thoracic, and abdominal - and contains three anatomical constrictions that are clinically important.

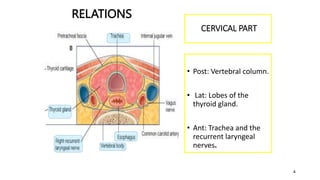

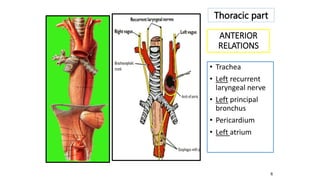

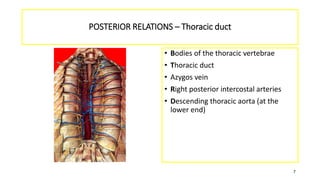

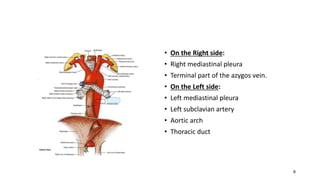

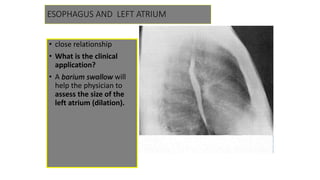

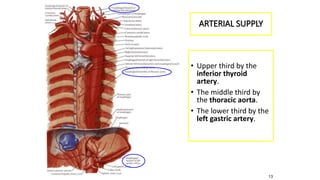

3. The esophagus has close relations with surrounding structures like the trachea, aorta and left atrium. Its blood supply comes from the inferior thyroid, thoracic aorta and left gastric arteries.