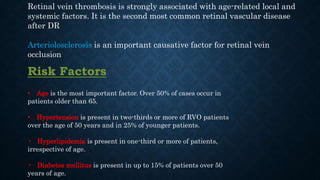

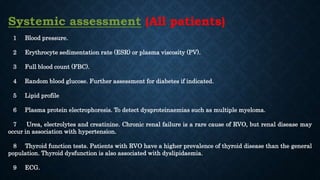

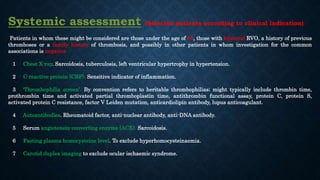

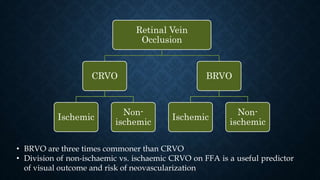

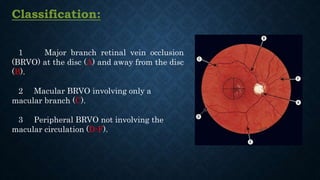

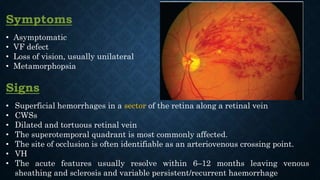

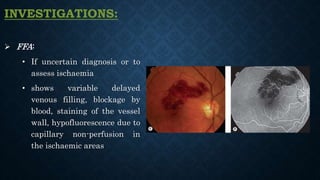

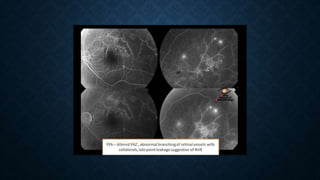

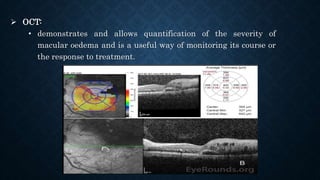

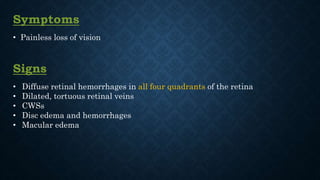

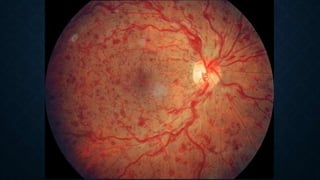

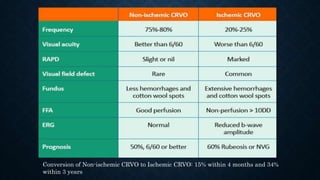

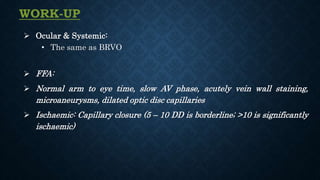

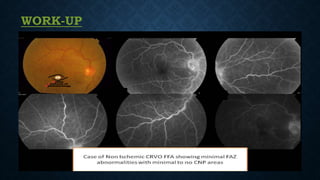

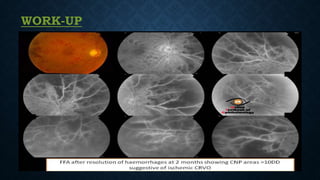

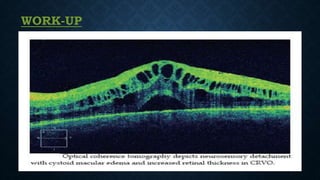

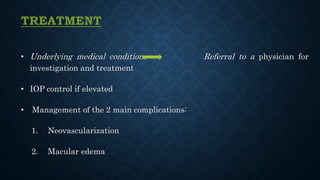

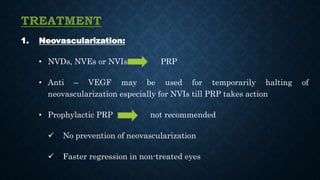

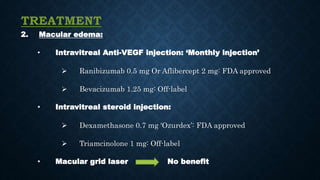

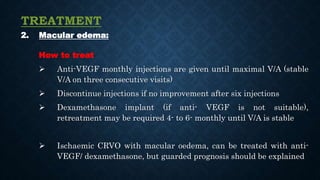

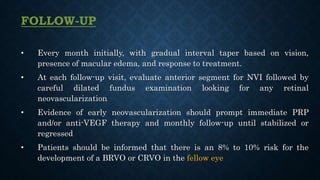

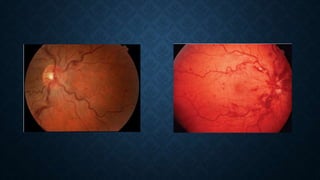

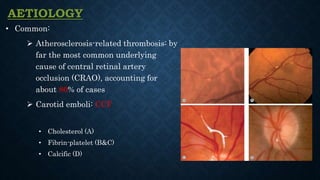

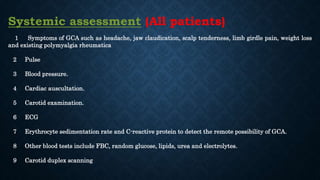

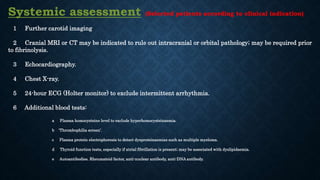

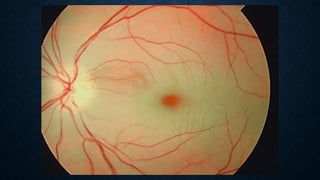

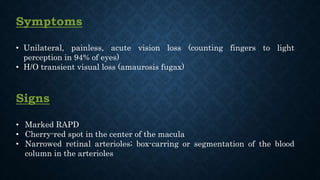

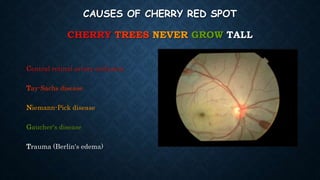

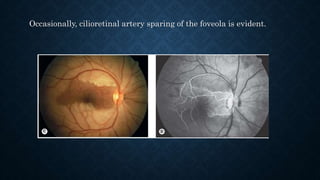

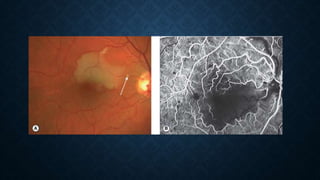

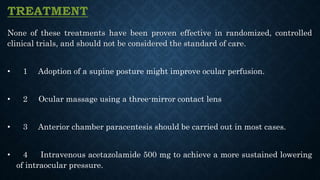

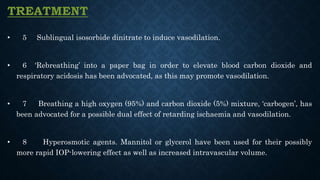

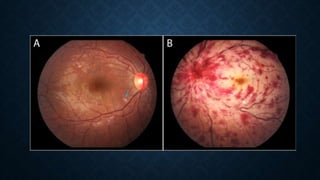

Retinal vascular diseases can cause vision loss. This document discusses retinal vein occlusion (RVO) and retinal artery occlusion (RAO). For RVO, it covers risk factors like age and hypertension. It also describes treatments for complications like neovascularization and macular edema using anti-VEGF injections or steroids. For RAO, it notes the cherry red spot sign and discusses potentially treating the underlying cause to prevent further vision loss in the fellow eye. Systemic workup aims to identify conditions like giant cell arteritis that require treatment to prevent bilateral involvement.