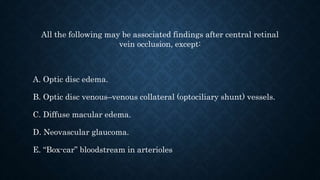

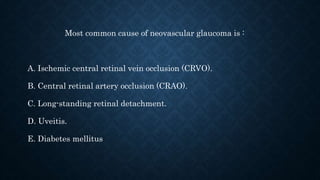

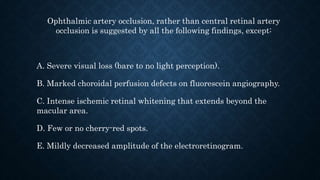

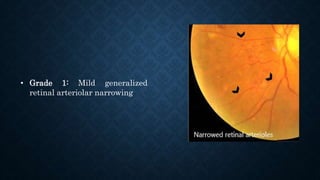

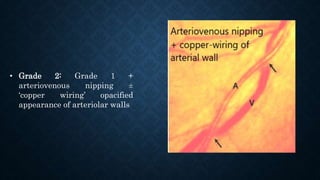

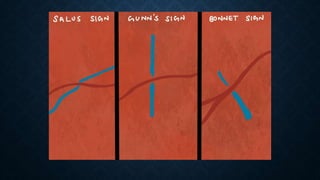

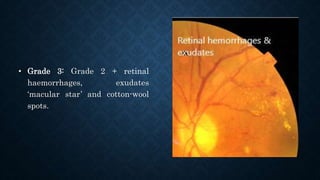

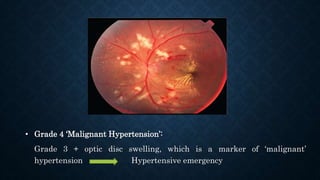

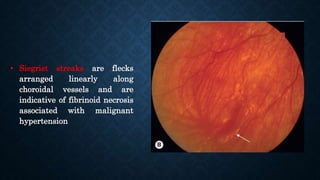

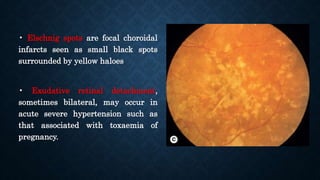

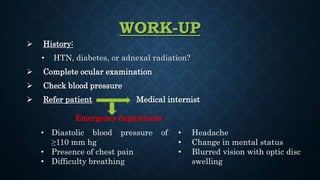

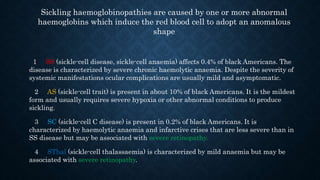

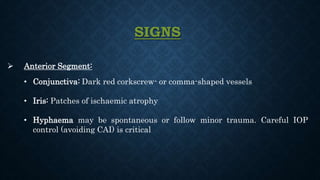

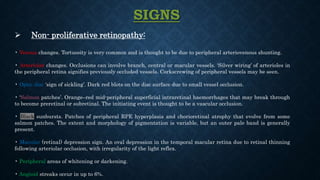

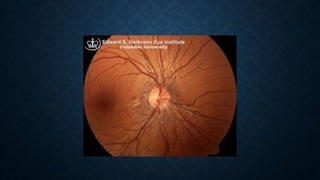

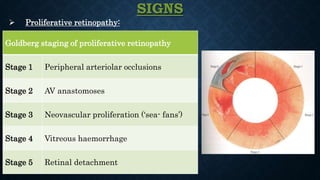

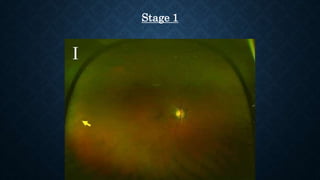

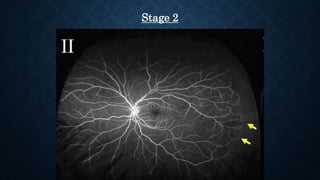

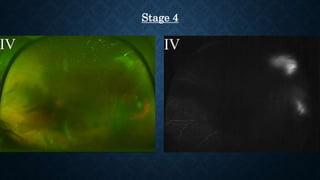

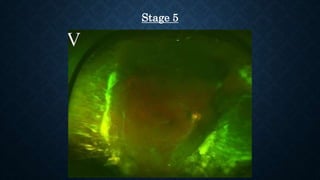

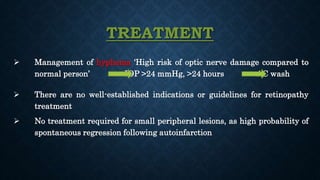

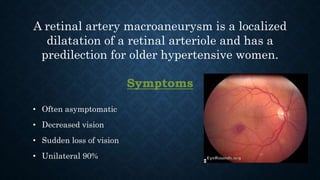

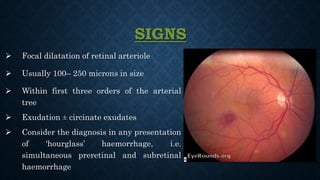

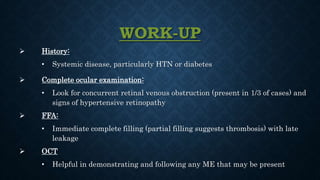

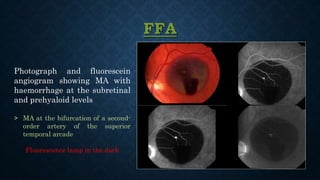

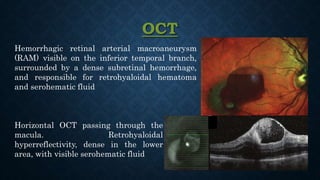

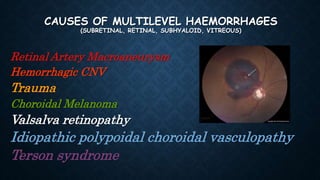

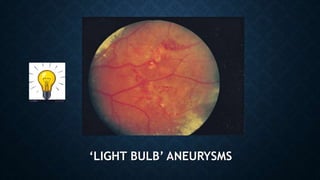

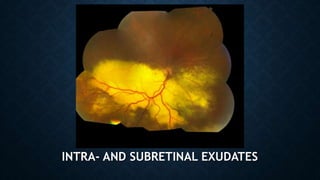

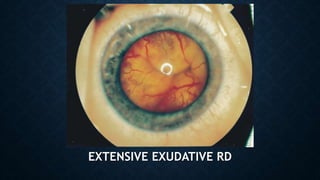

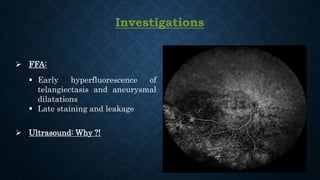

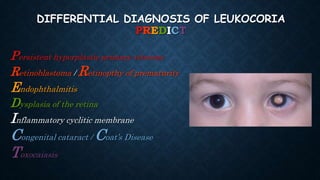

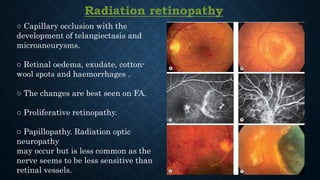

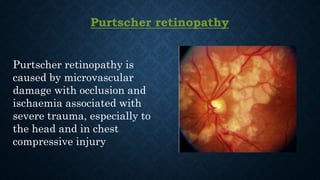

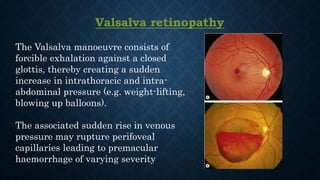

This document discusses various retinal vascular diseases and associated findings. It covers central retinal vein occlusion and the associated findings except for neovascular glaucoma. It notes that the most common cause of neovascular glaucoma is ischemic central retinal vein occlusion. The document also discusses ophthalmic artery occlusion findings compared to central retinal artery occlusion. Additional topics covered include hypertensive retinopathy, sickle cell retinopathy, Coats disease, retinal artery macroaneurysms, and other retinal conditions like radiation retinopathy. Treatment options are provided for several of the conditions.