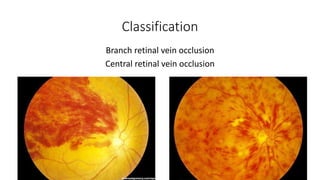

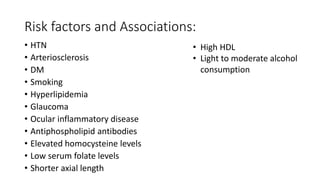

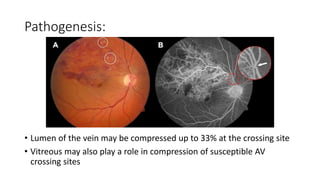

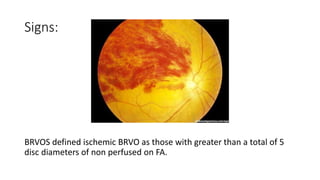

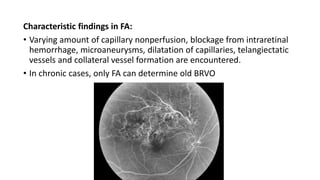

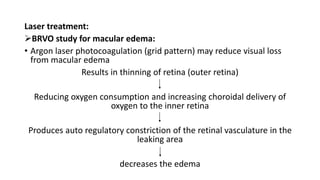

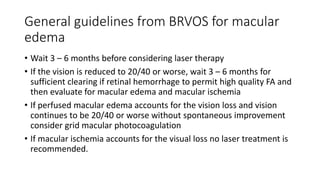

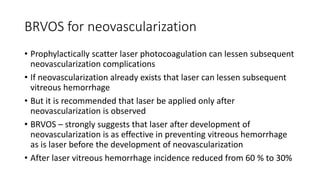

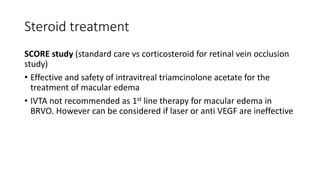

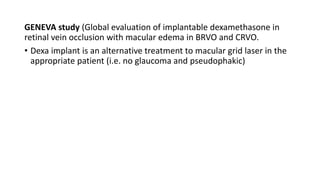

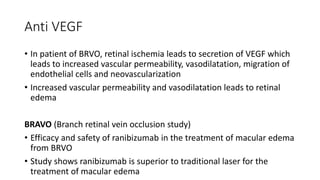

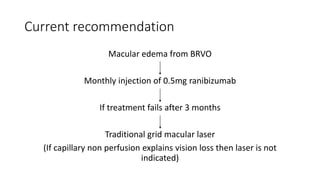

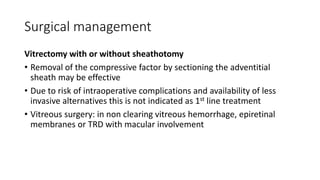

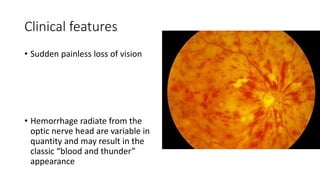

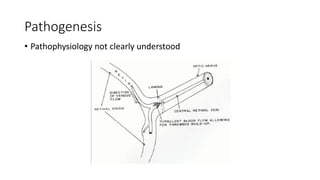

This document discusses retinal vein occlusion, specifically branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) and central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). It covers the epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, treatment options including laser photocoagulation, corticosteroids and anti-VEGF drugs, and complications such as macular edema and neovascularization. Key points include that BRVO most commonly affects the superotemporal quadrant and that perfusion status on fluorescein angiography helps determine prognosis for CRVO.