This document provides an overview of probability concepts including:

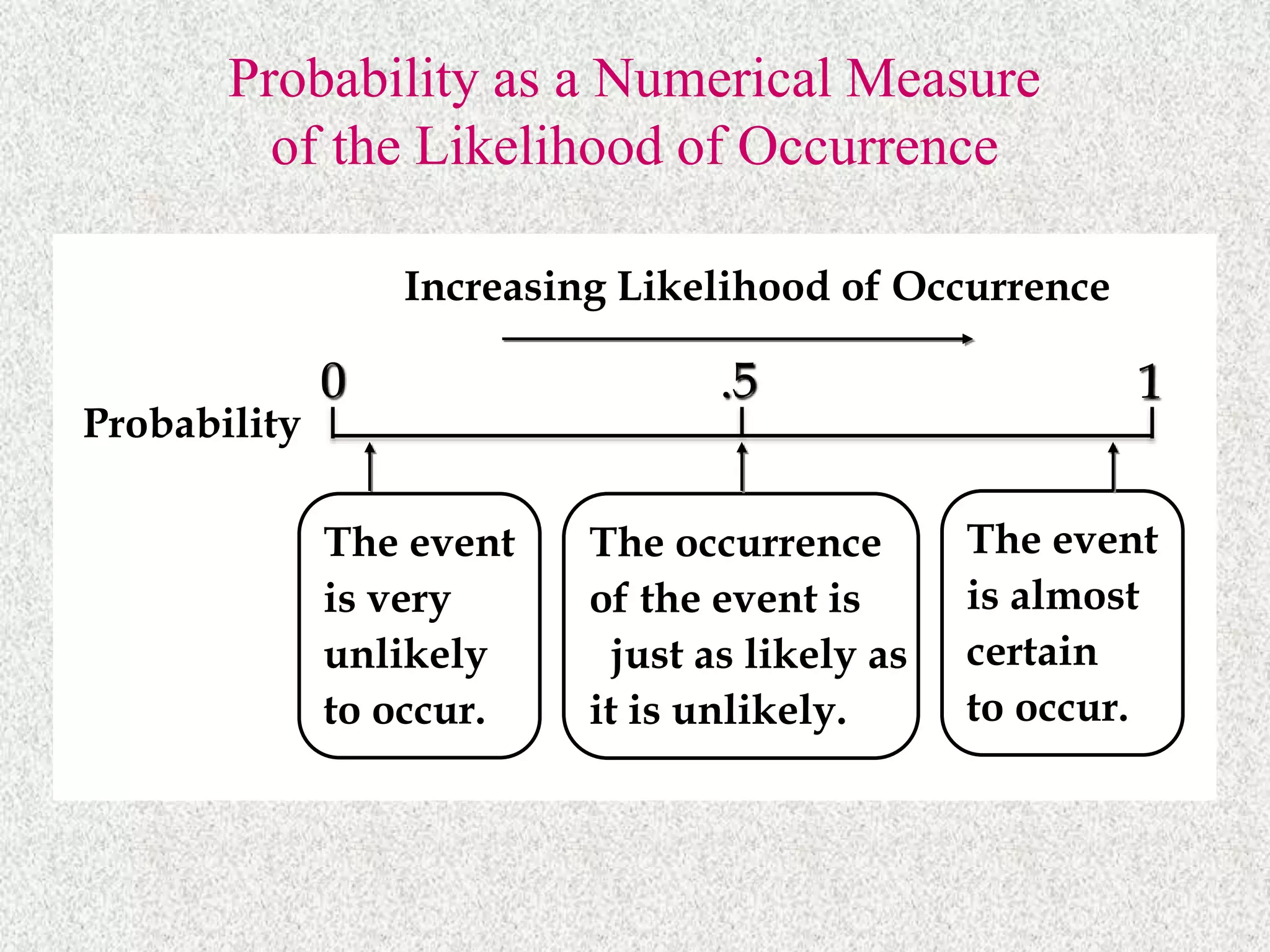

- Probability is a numerical measure of the likelihood of an event occurring, ranging from 0 (impossible) to 1 (certain).

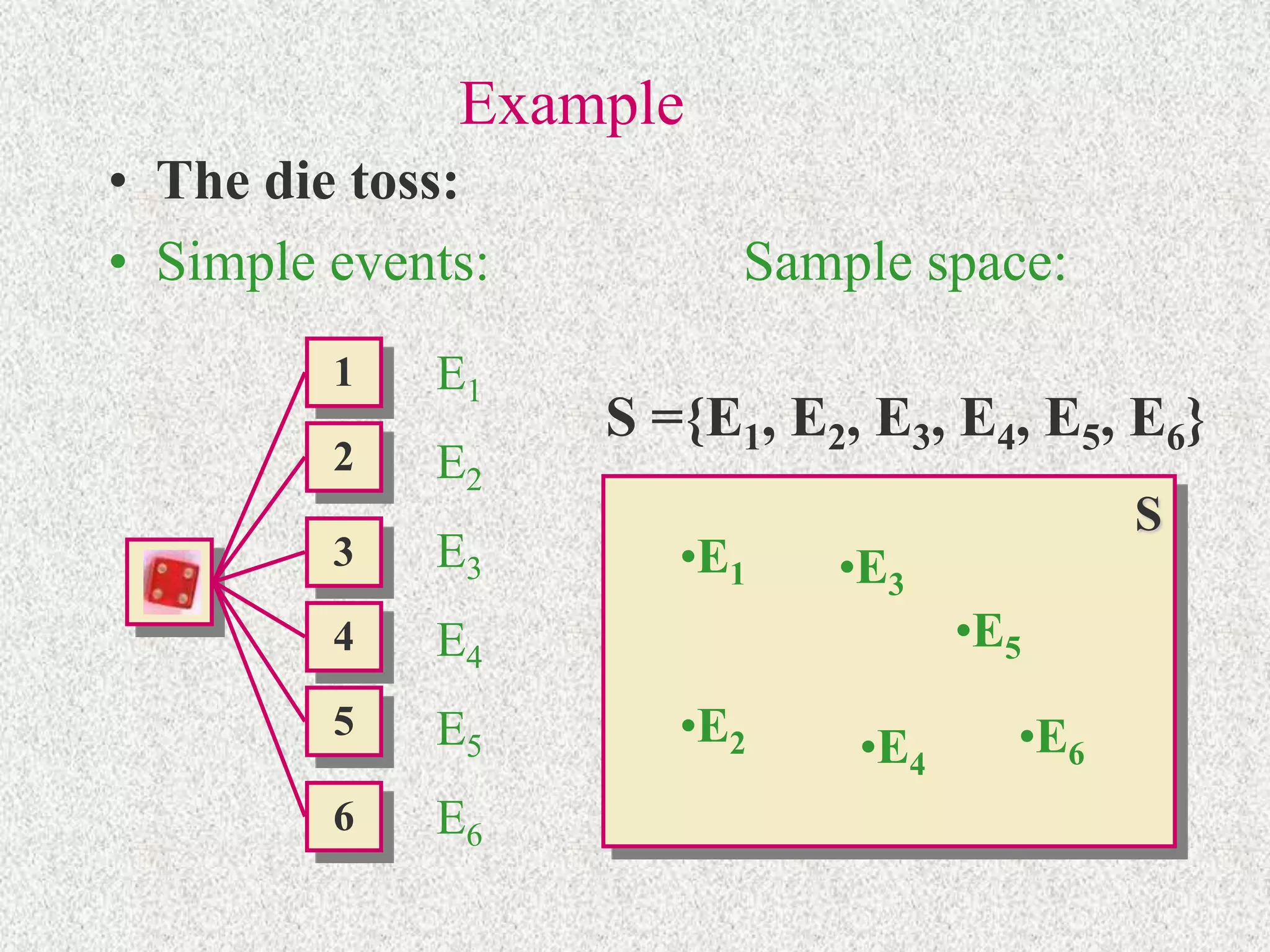

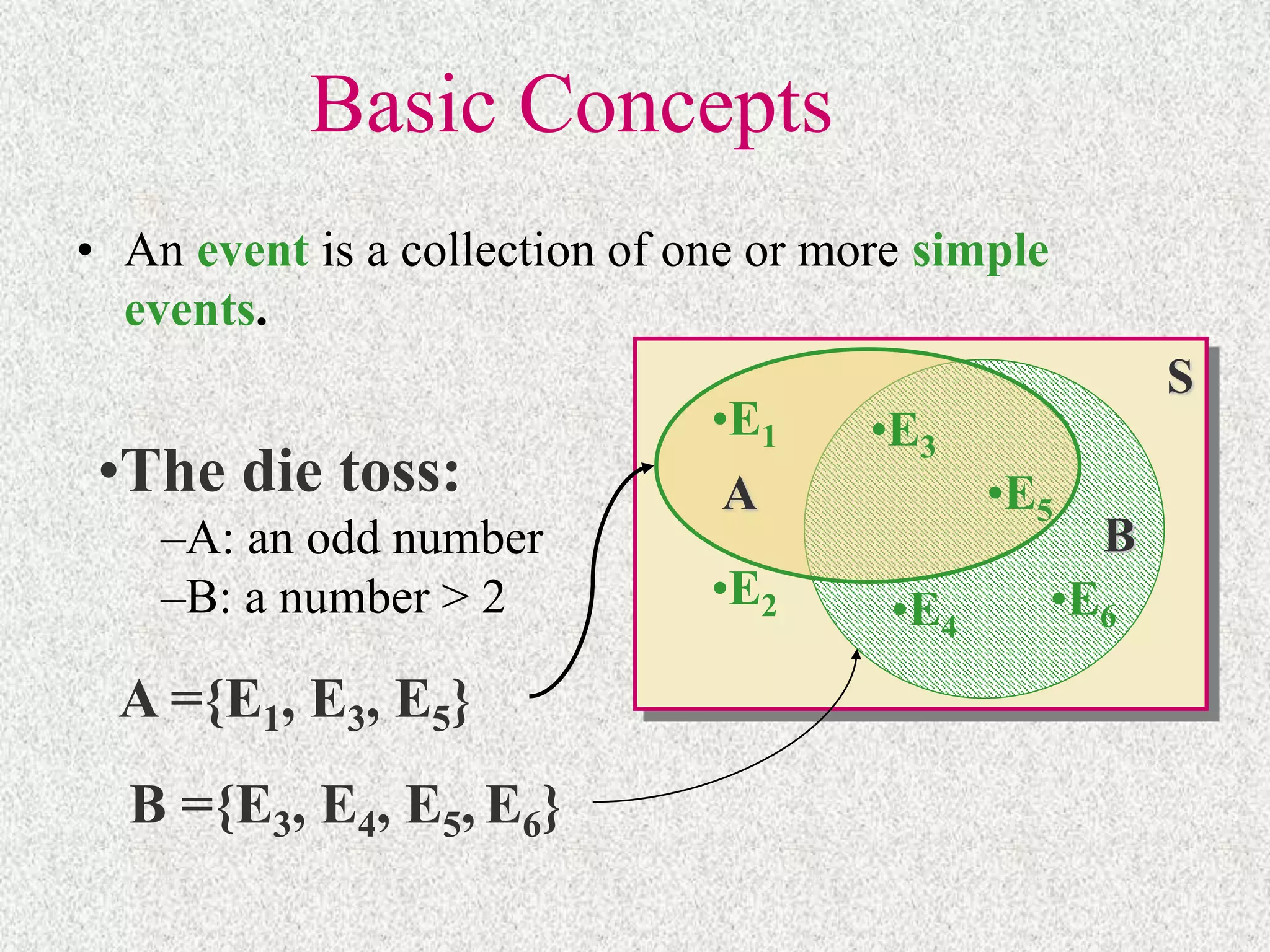

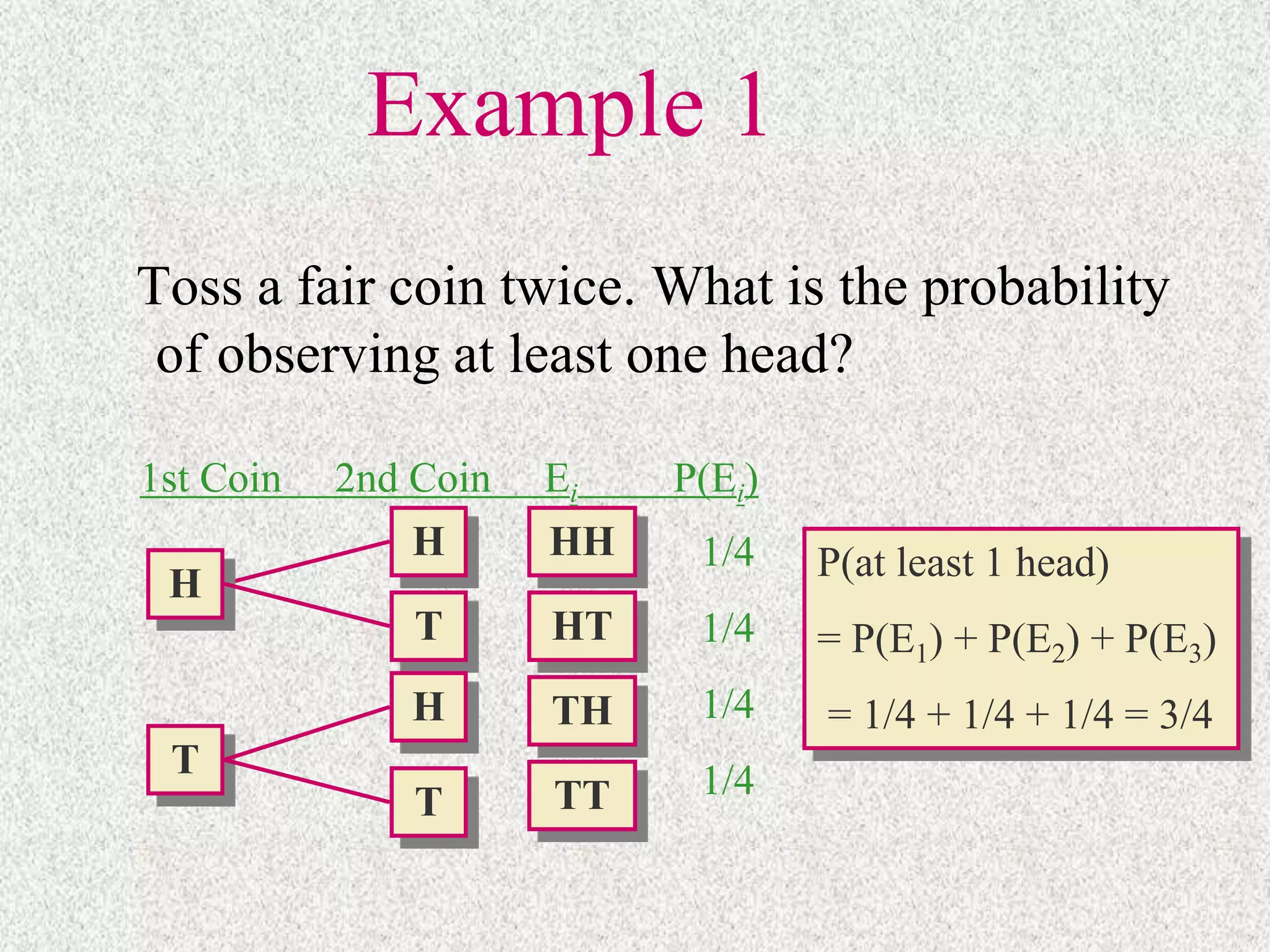

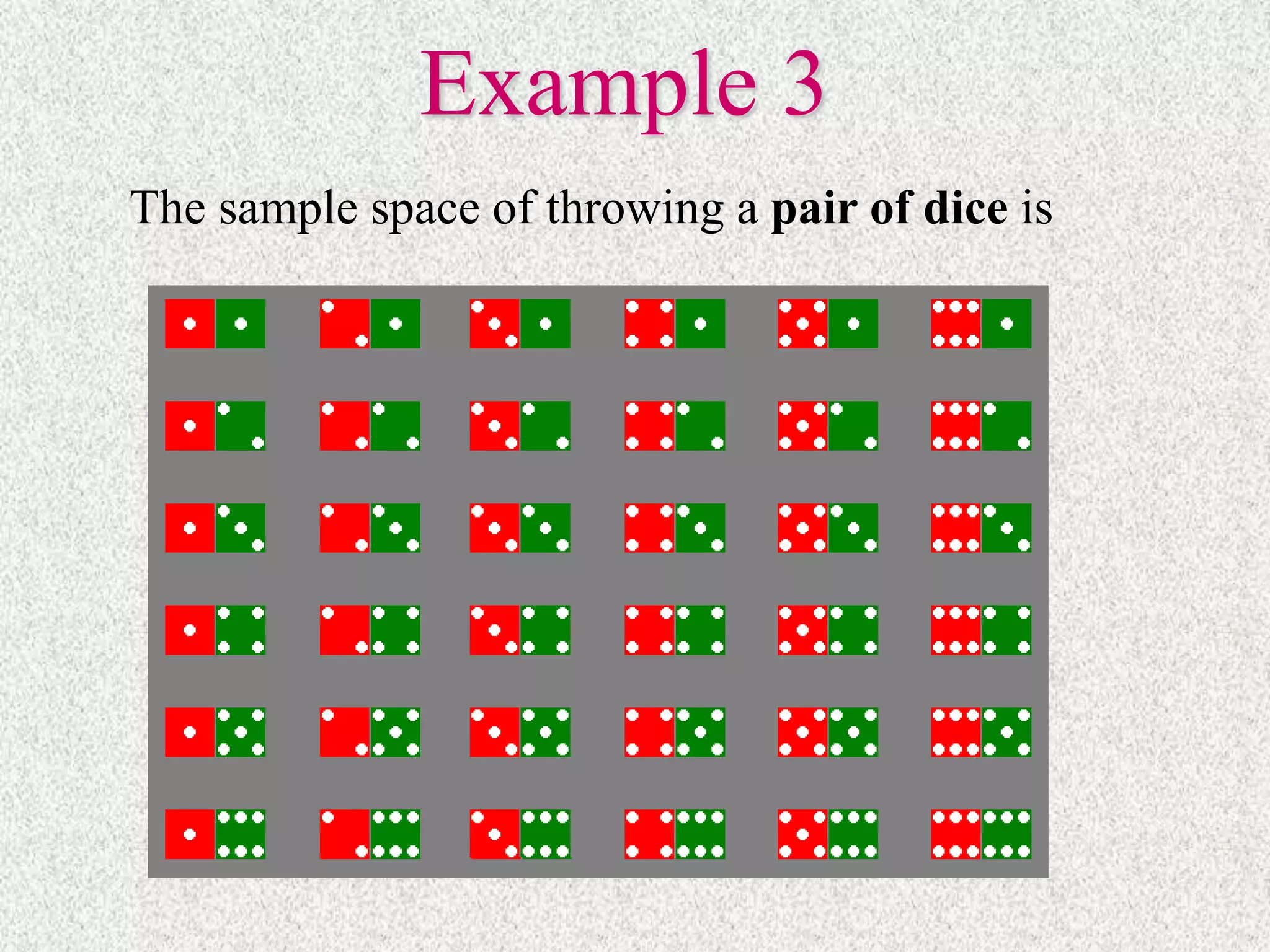

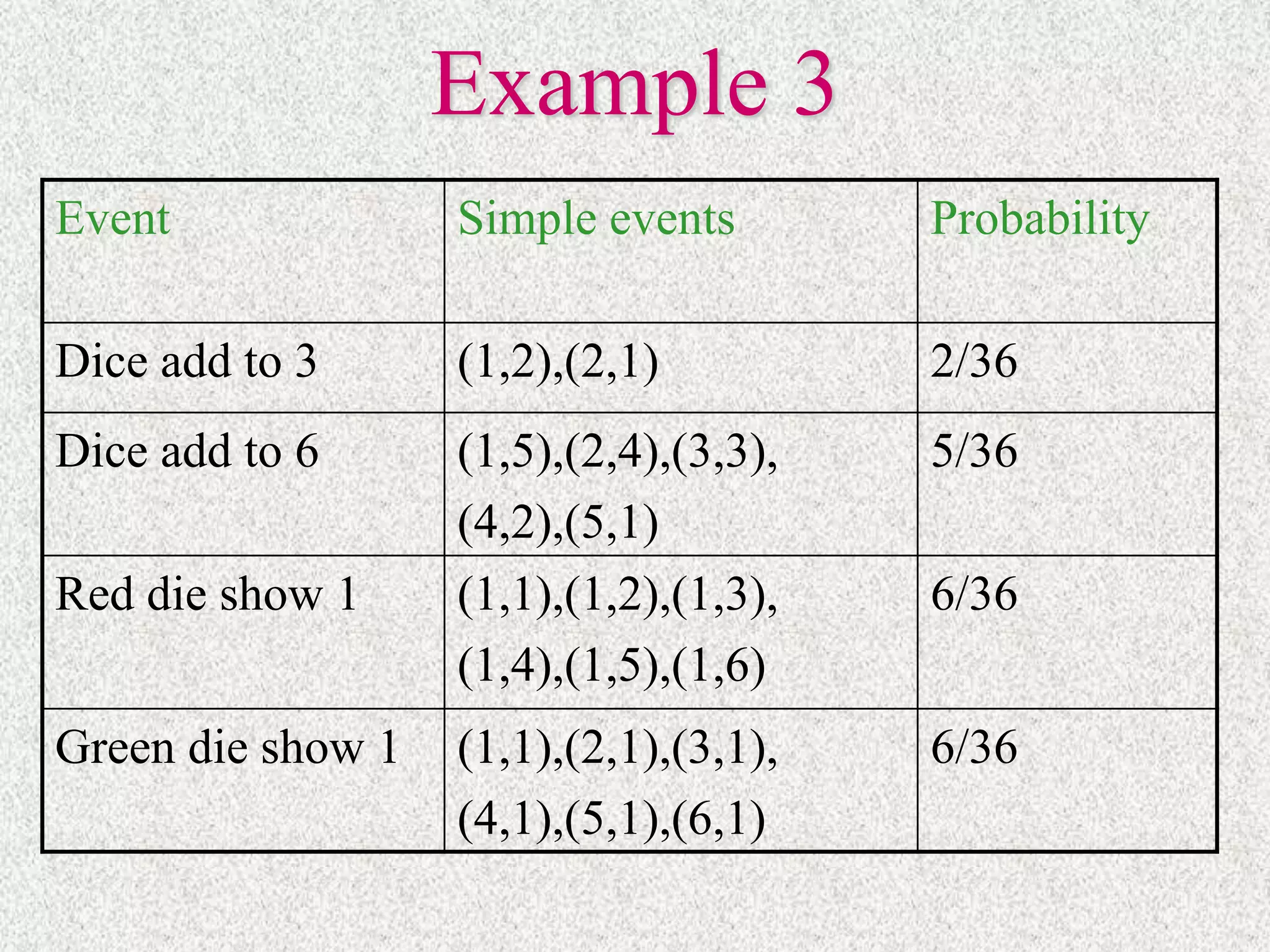

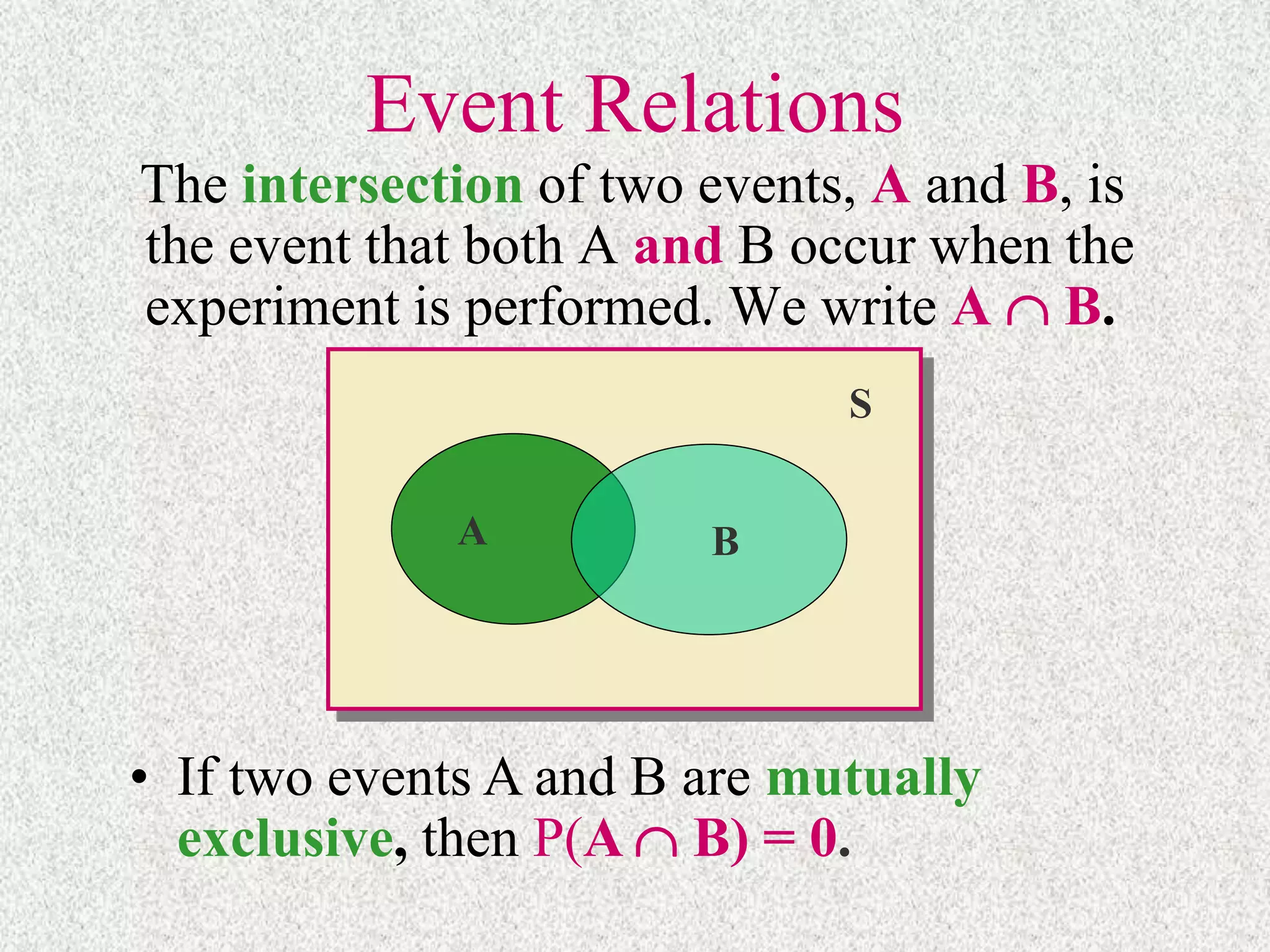

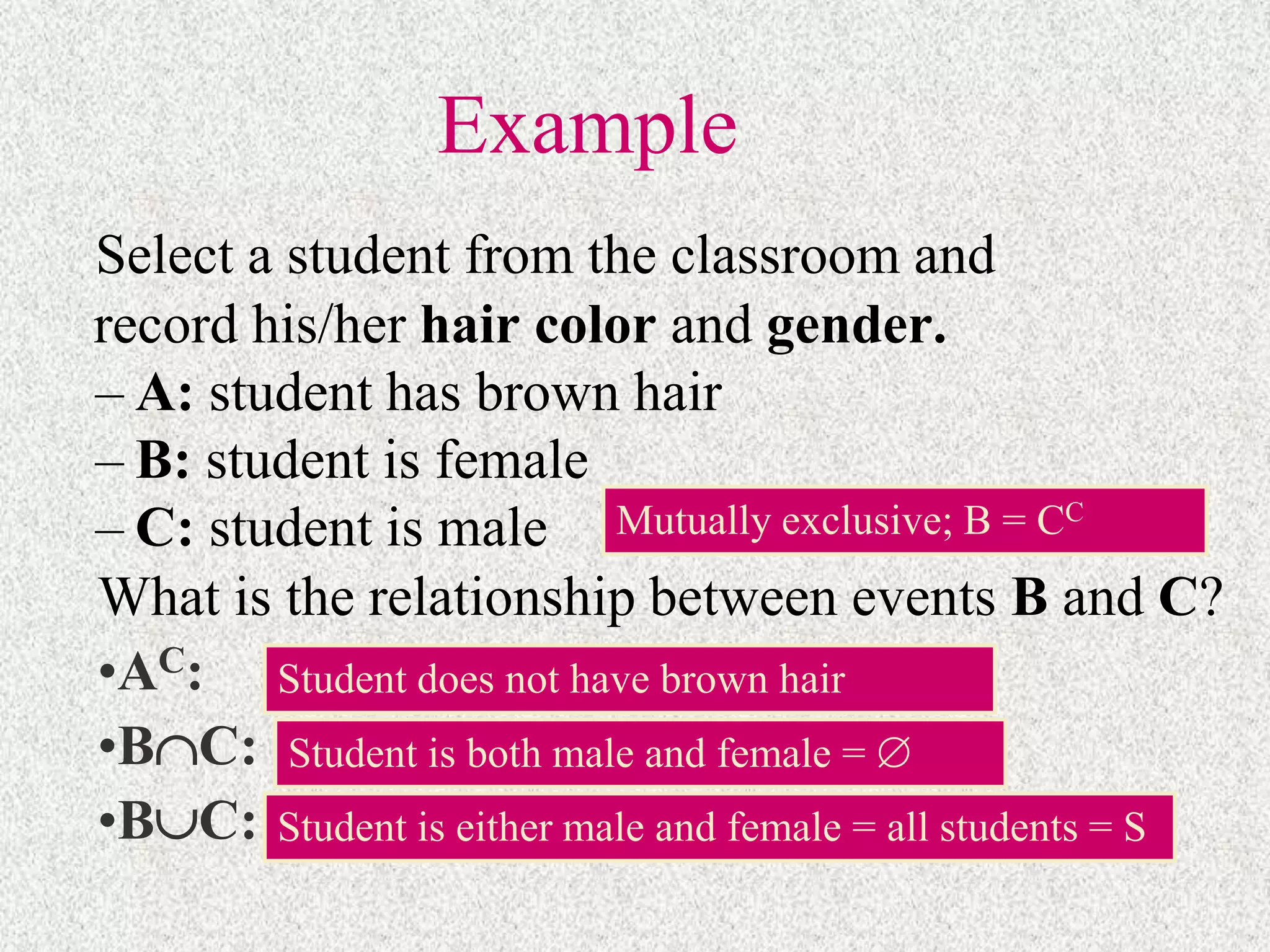

- An experiment generates outcomes that make up the sample space. Events are collections of outcomes.

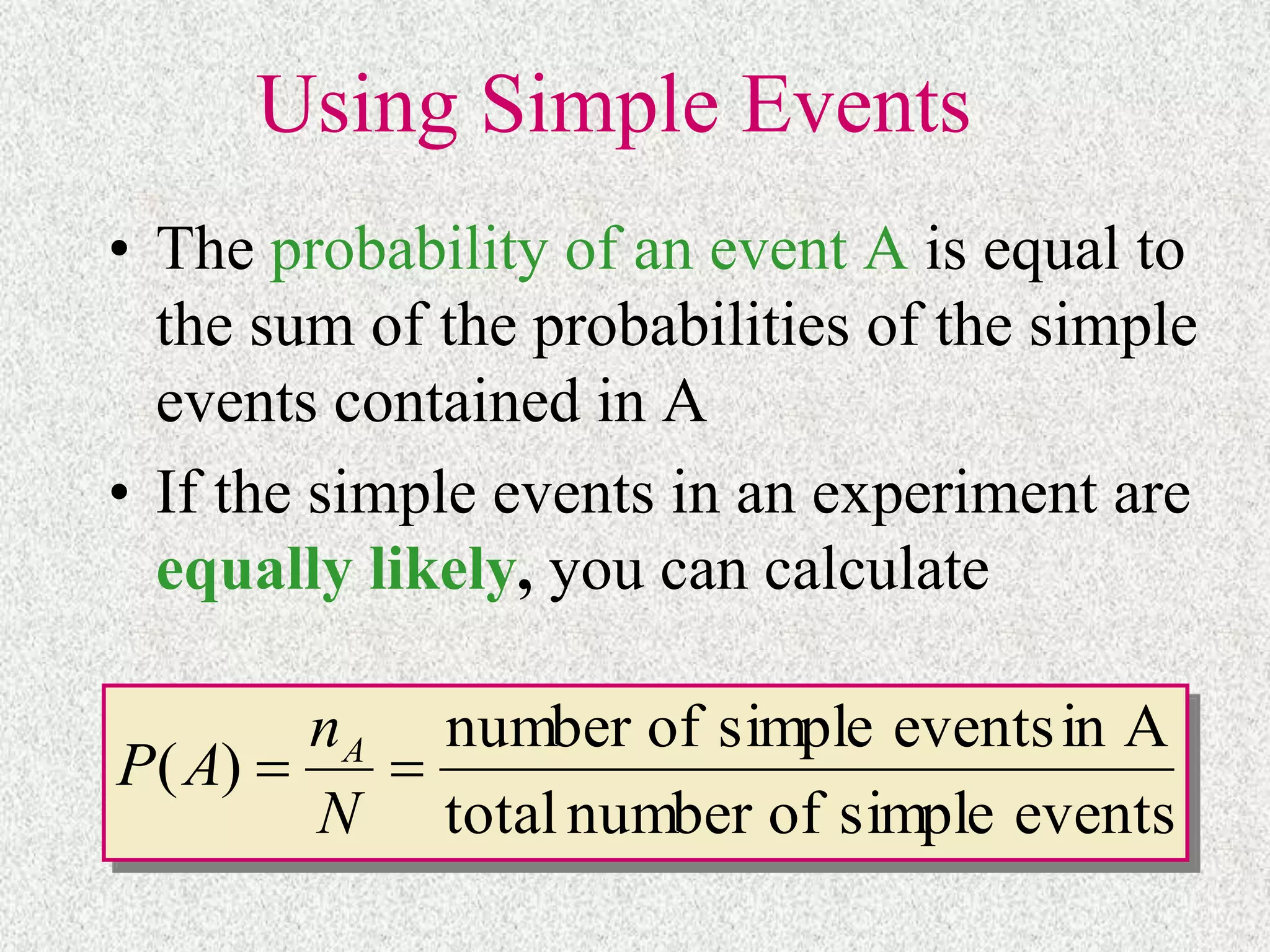

- Simple events have a defined probability based on being equally likely. The probability of an event is the sum of probabilities of the simple events it contains.

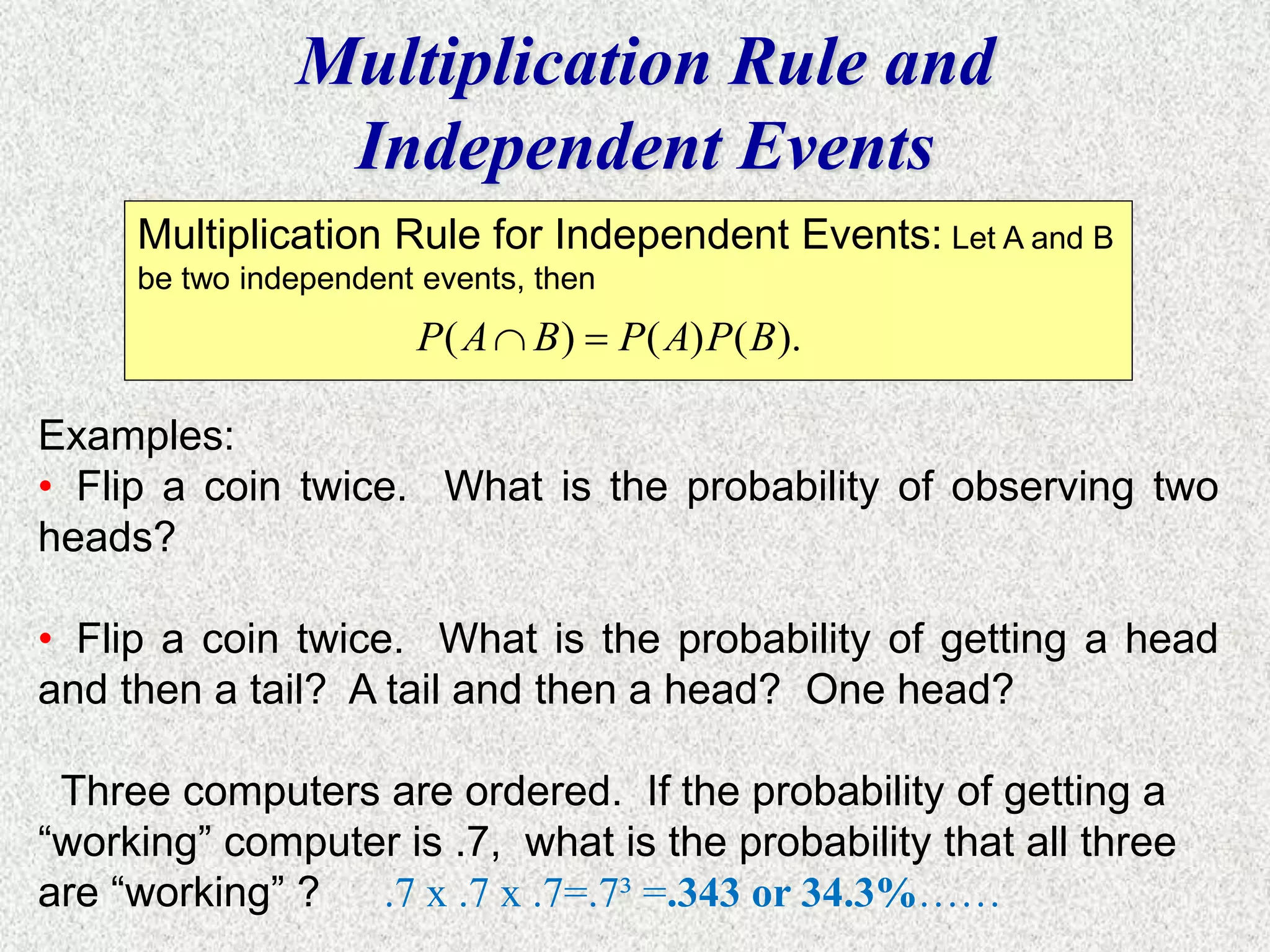

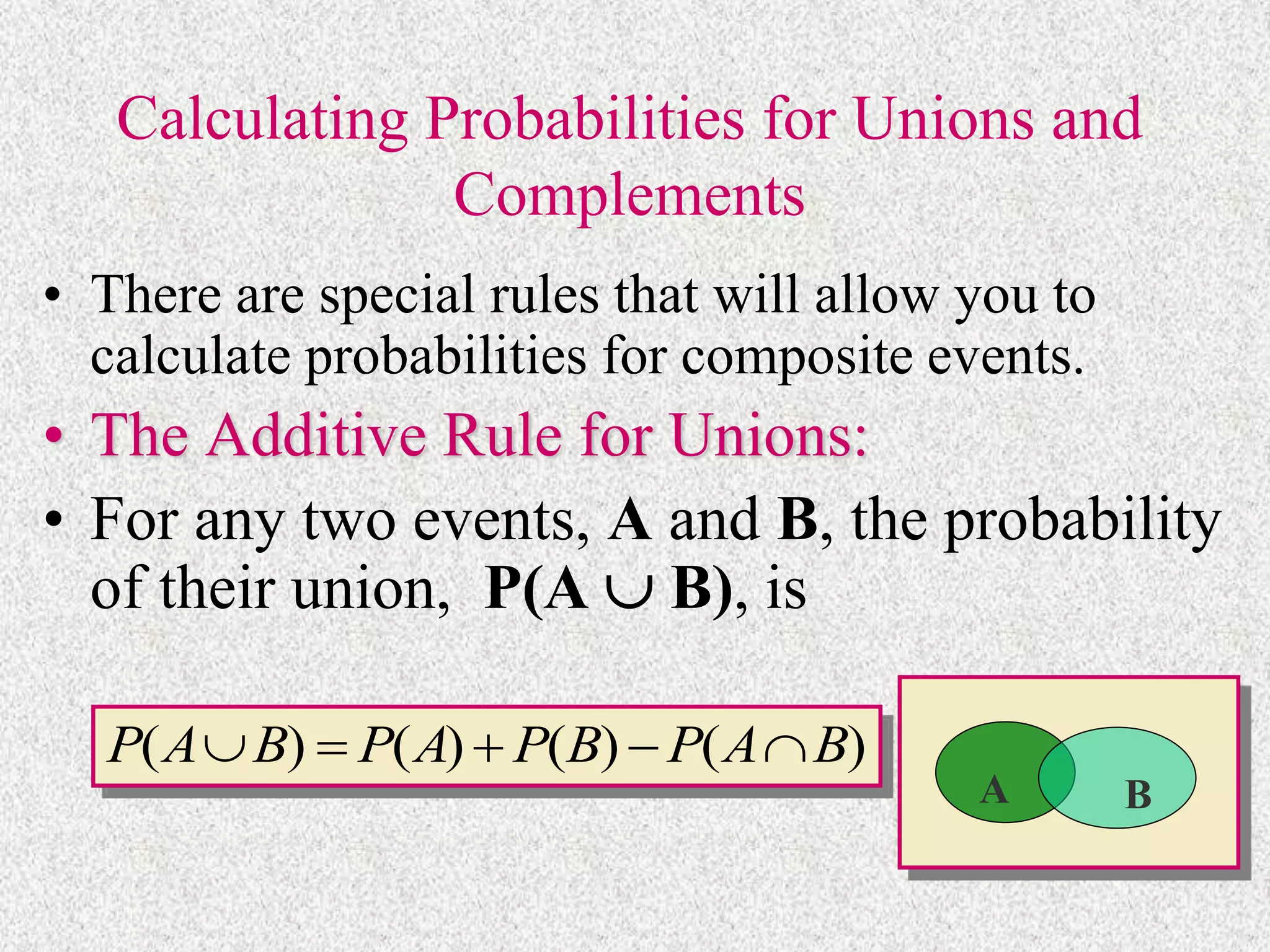

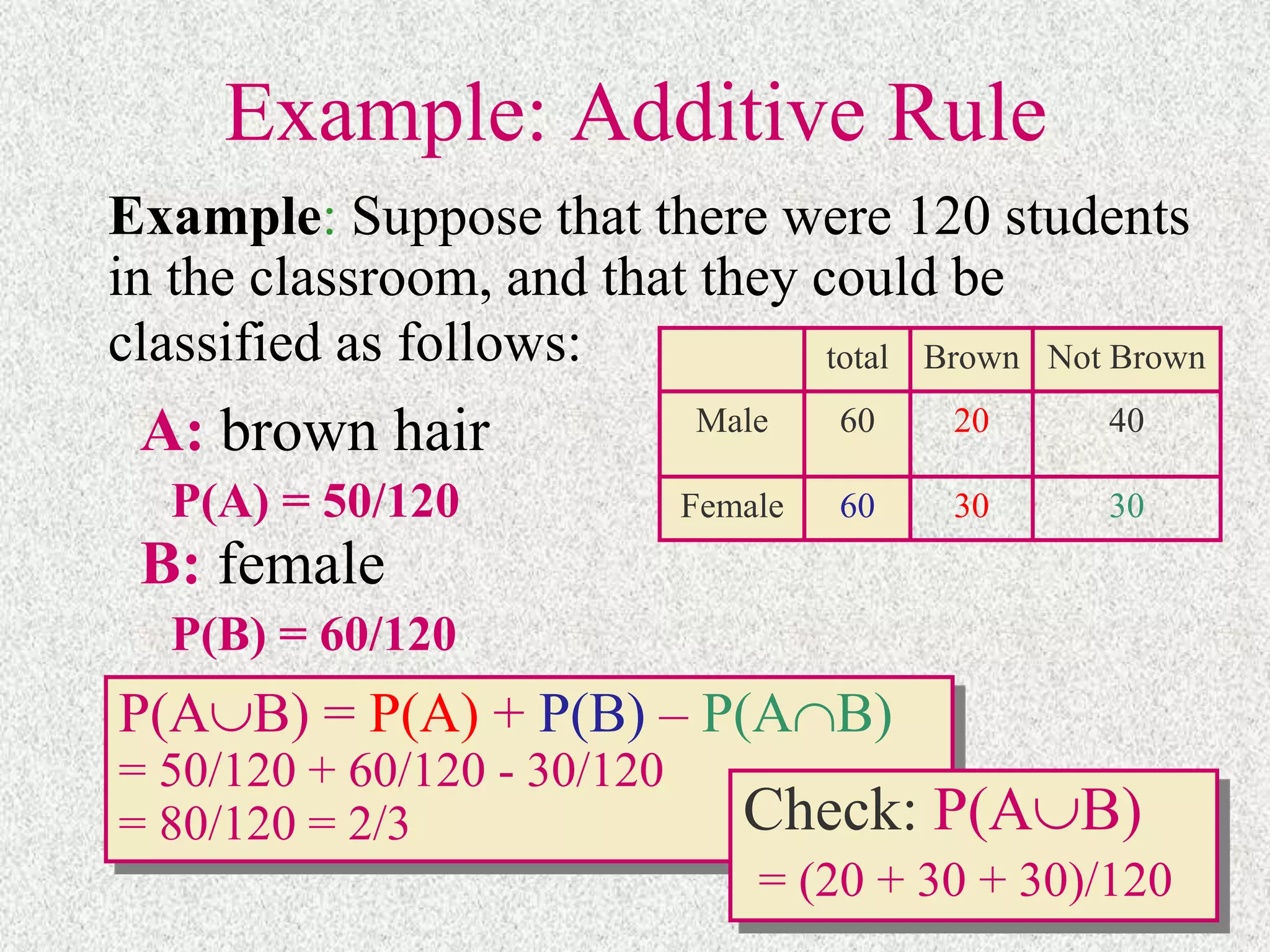

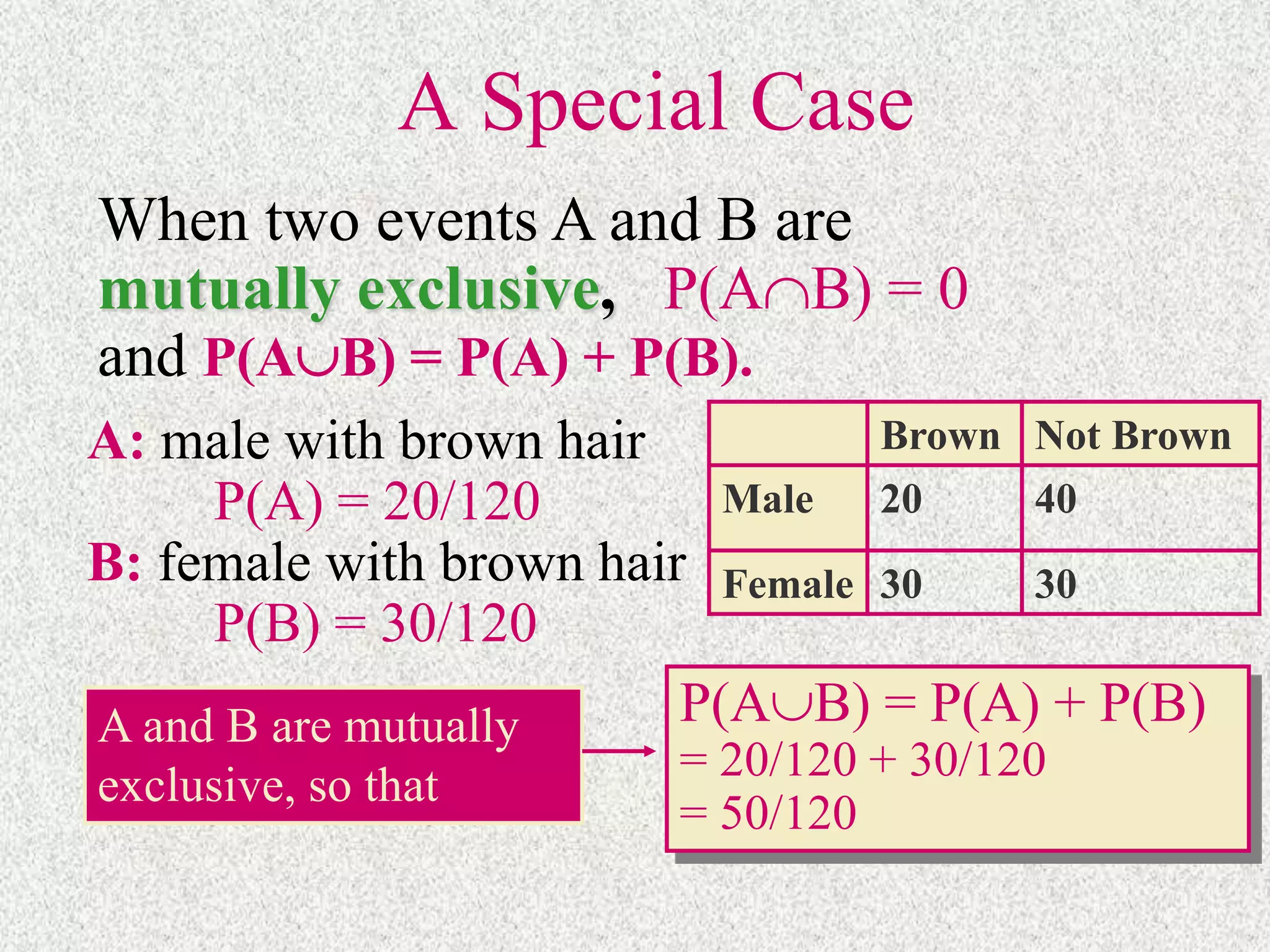

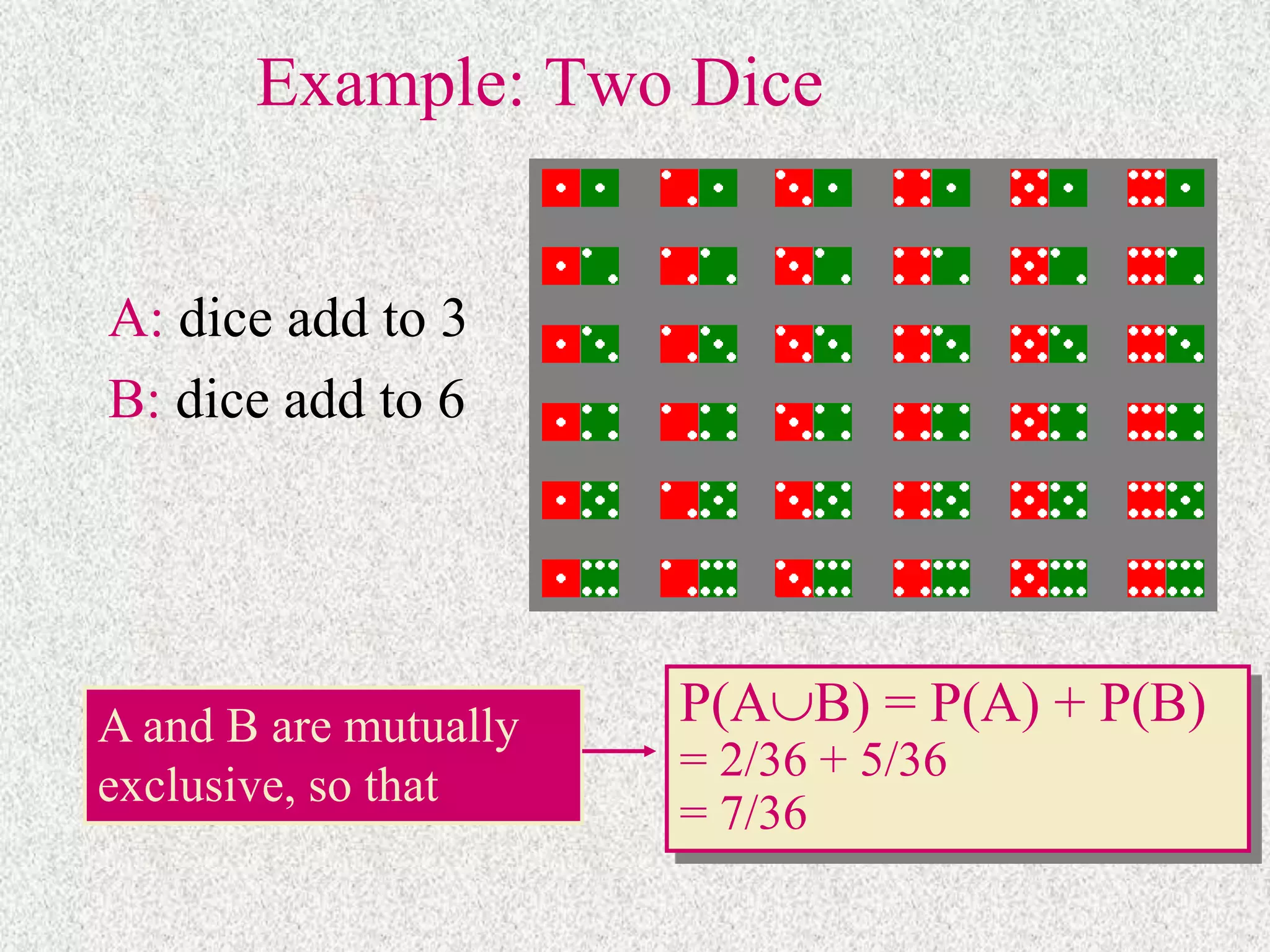

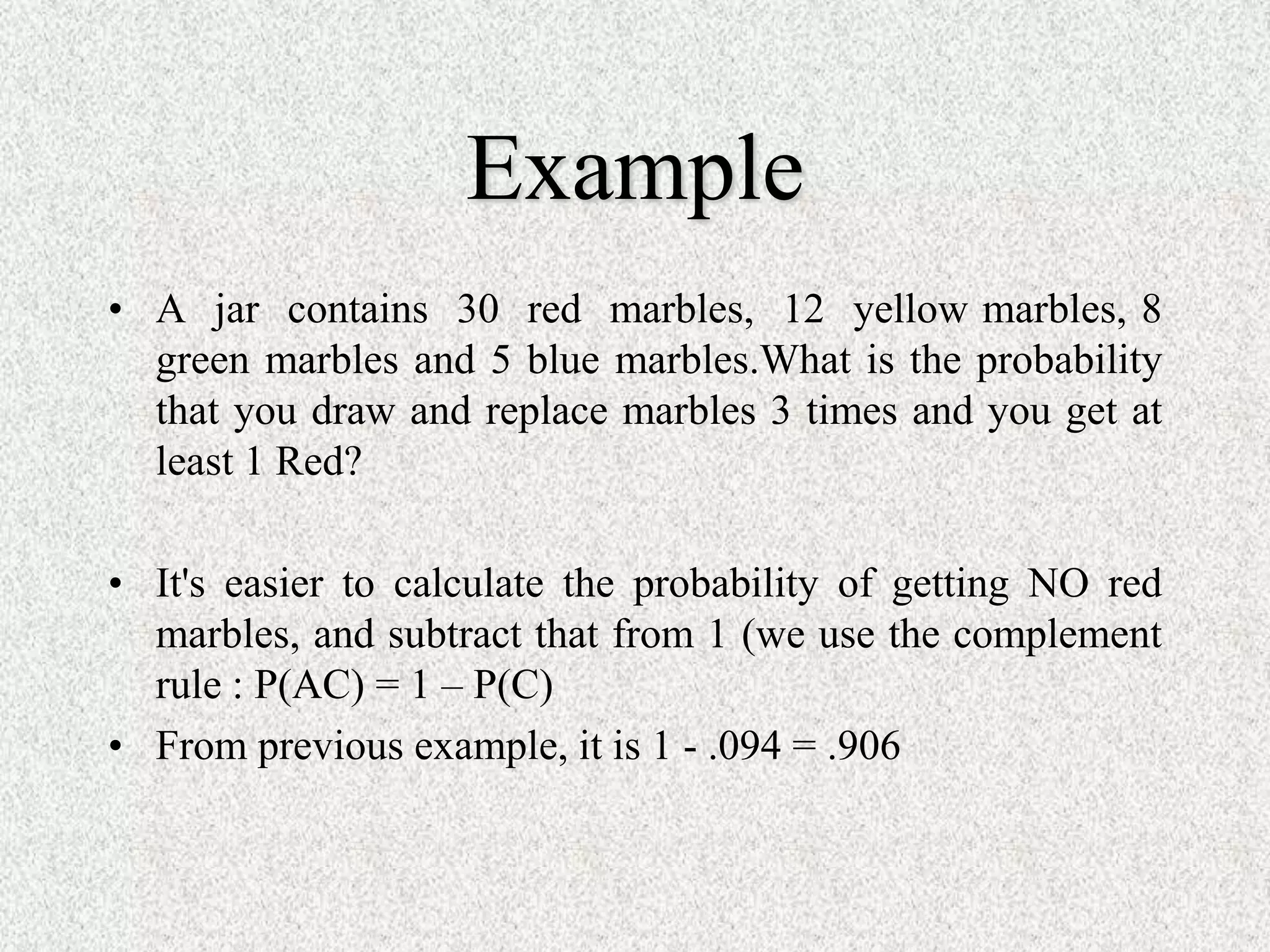

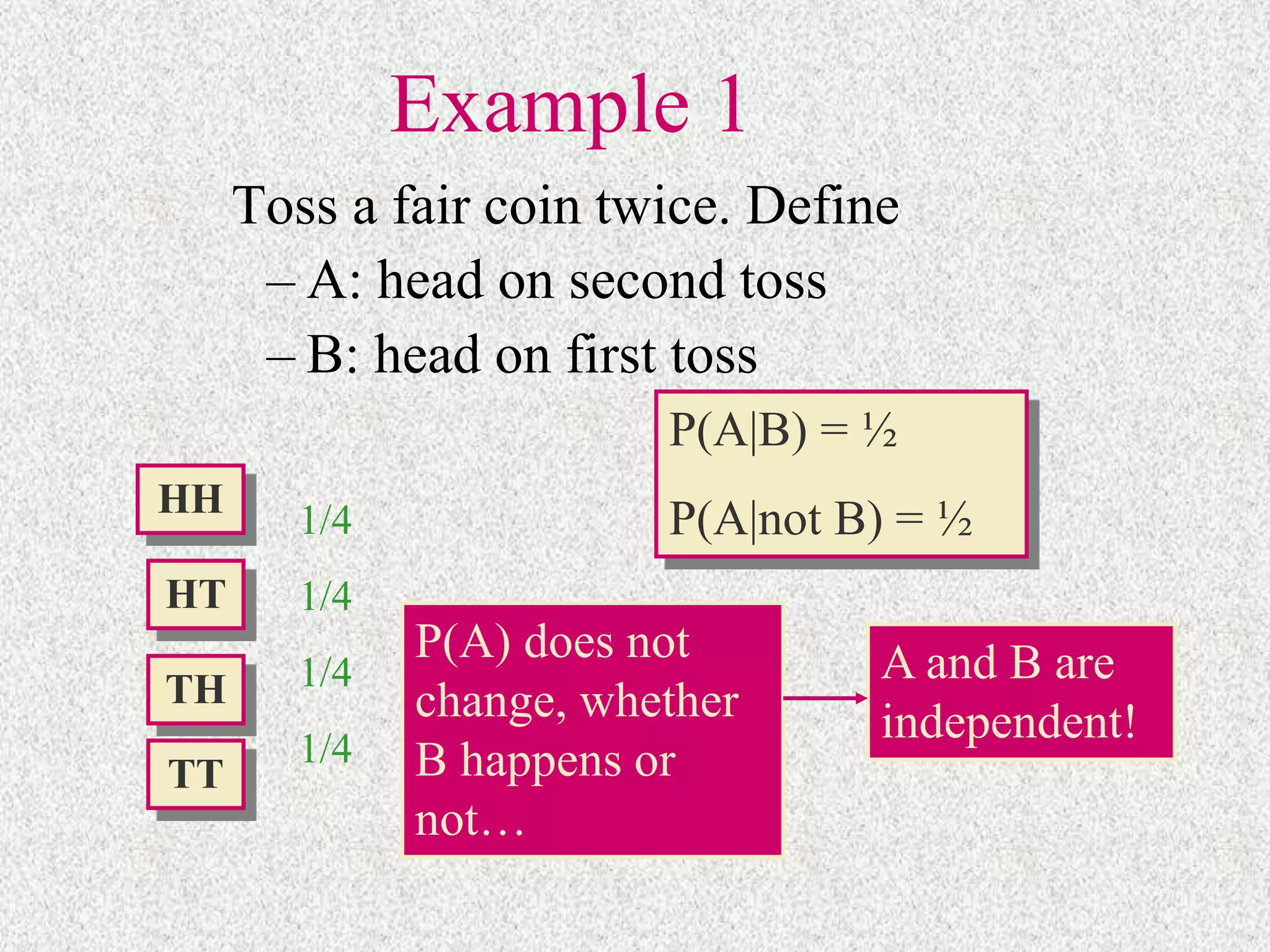

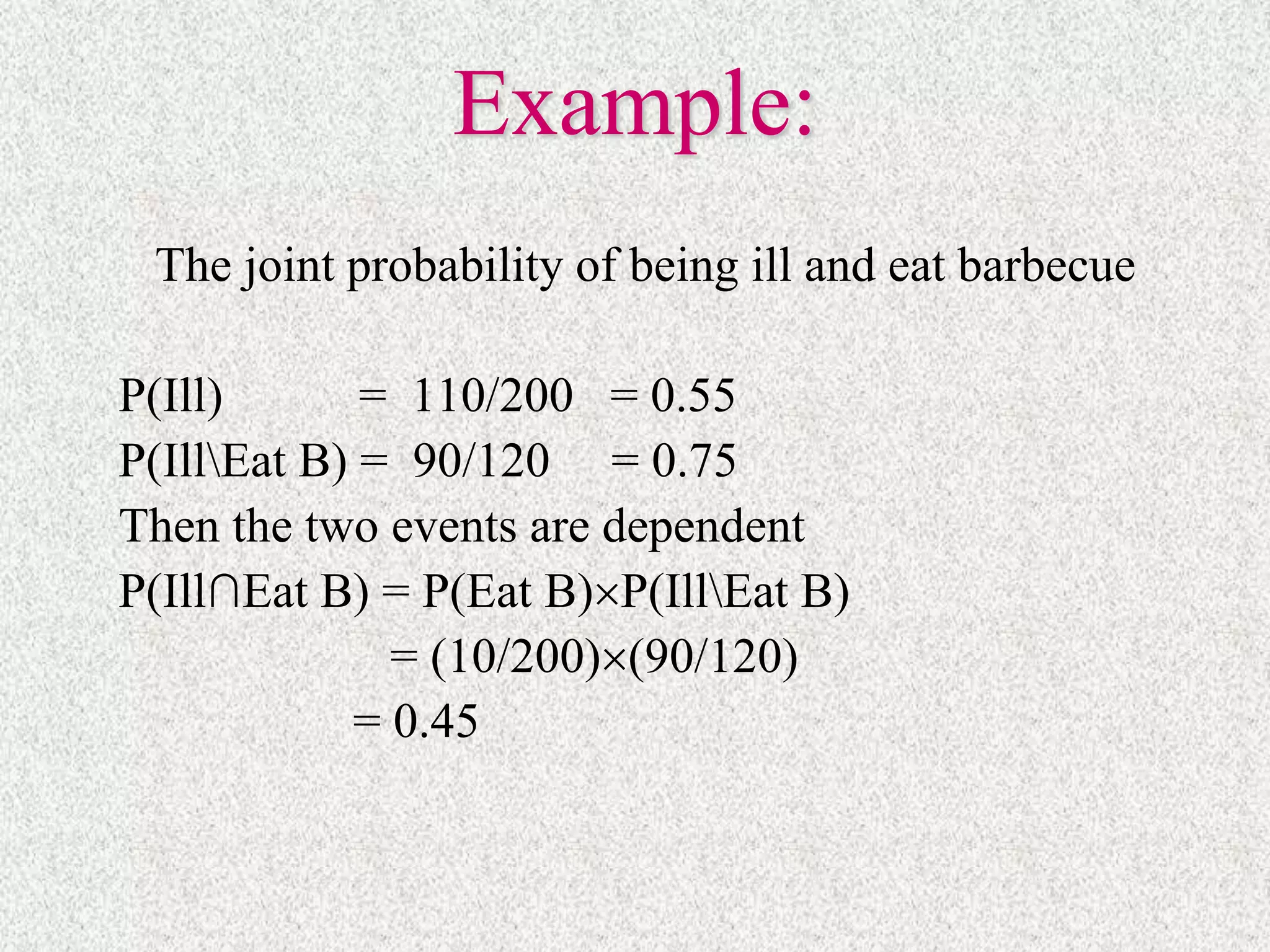

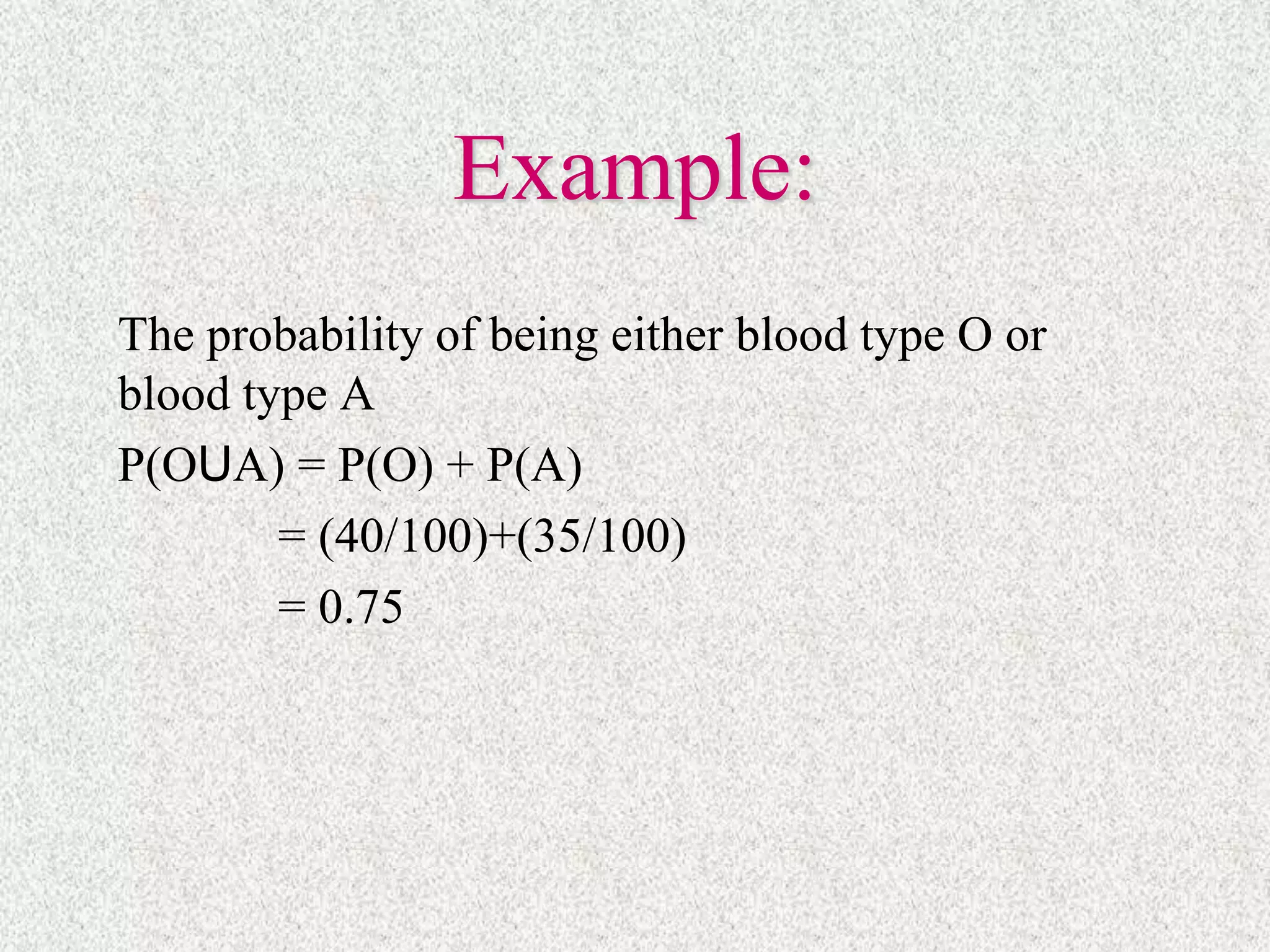

- Rules like the multiplication rule for independent events and additive rule for unions allow calculating probabilities of composite events.

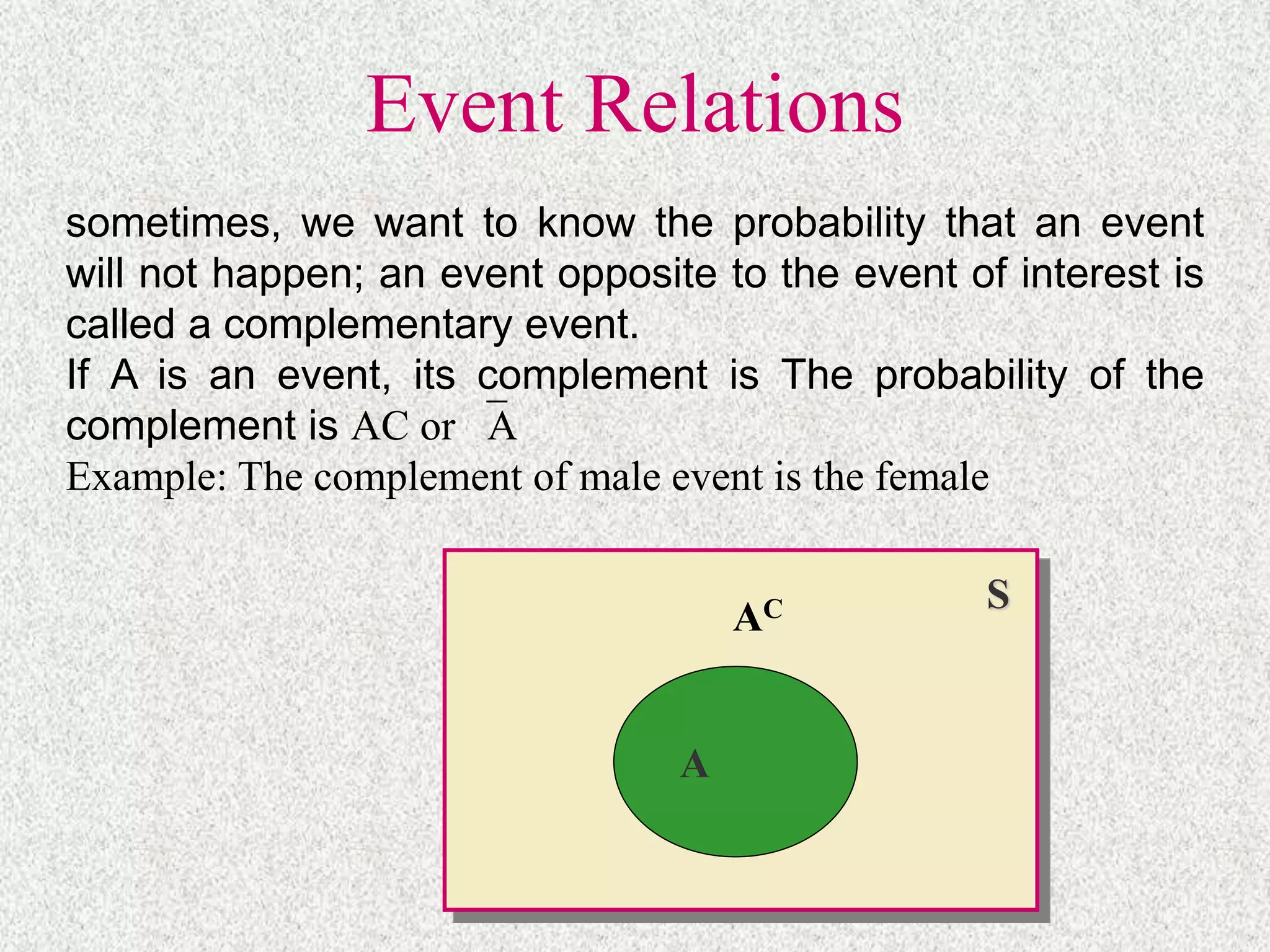

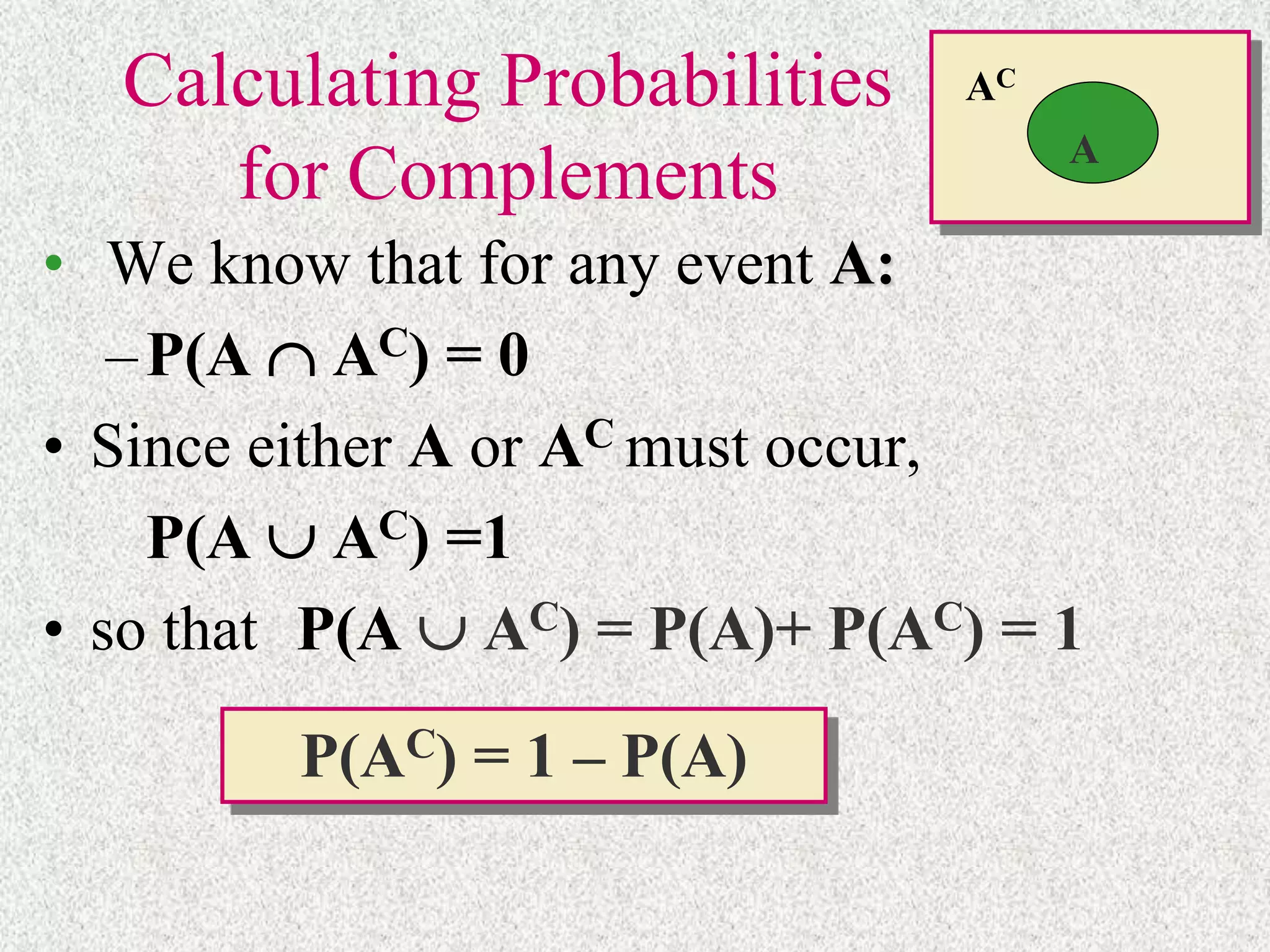

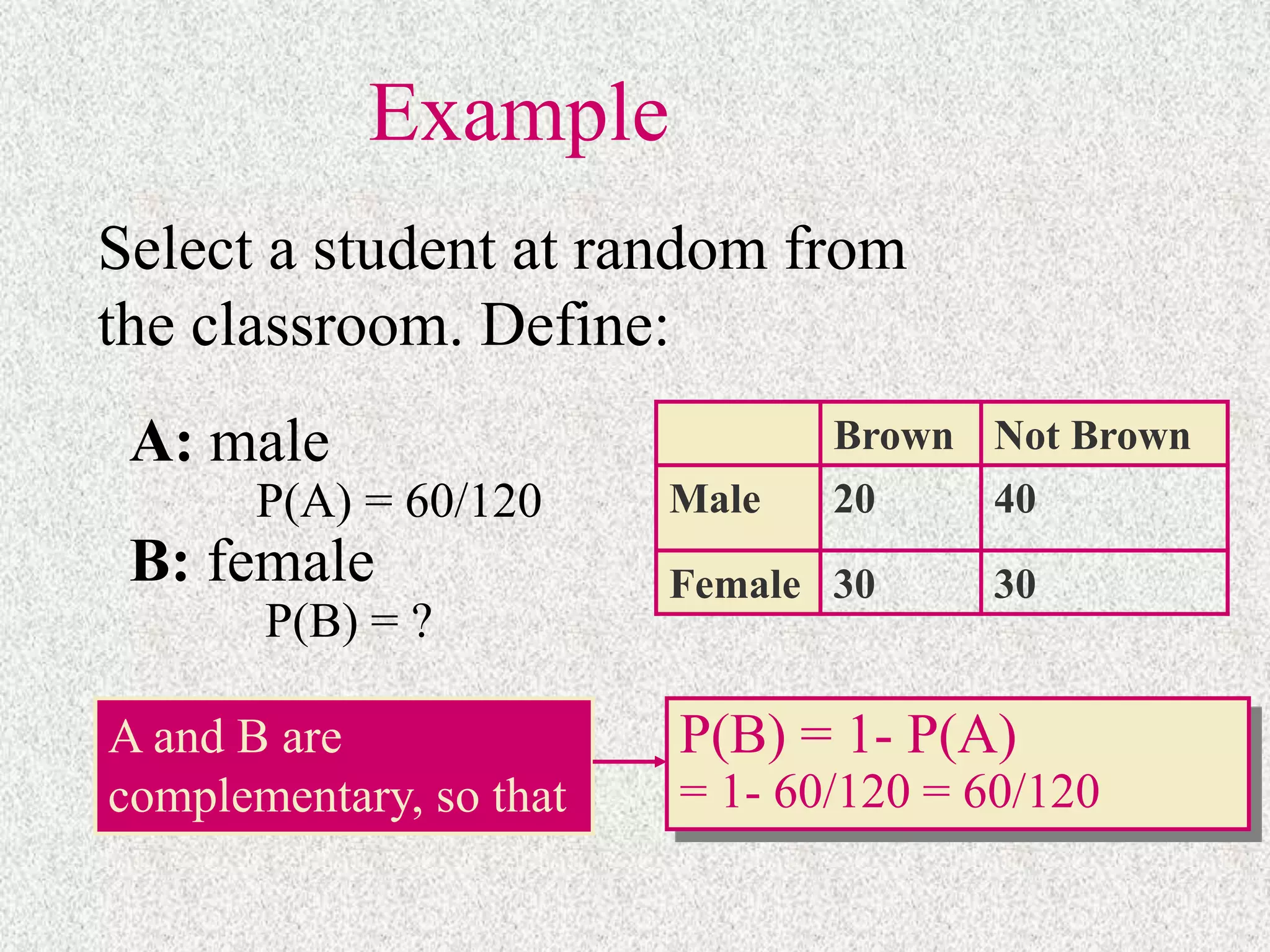

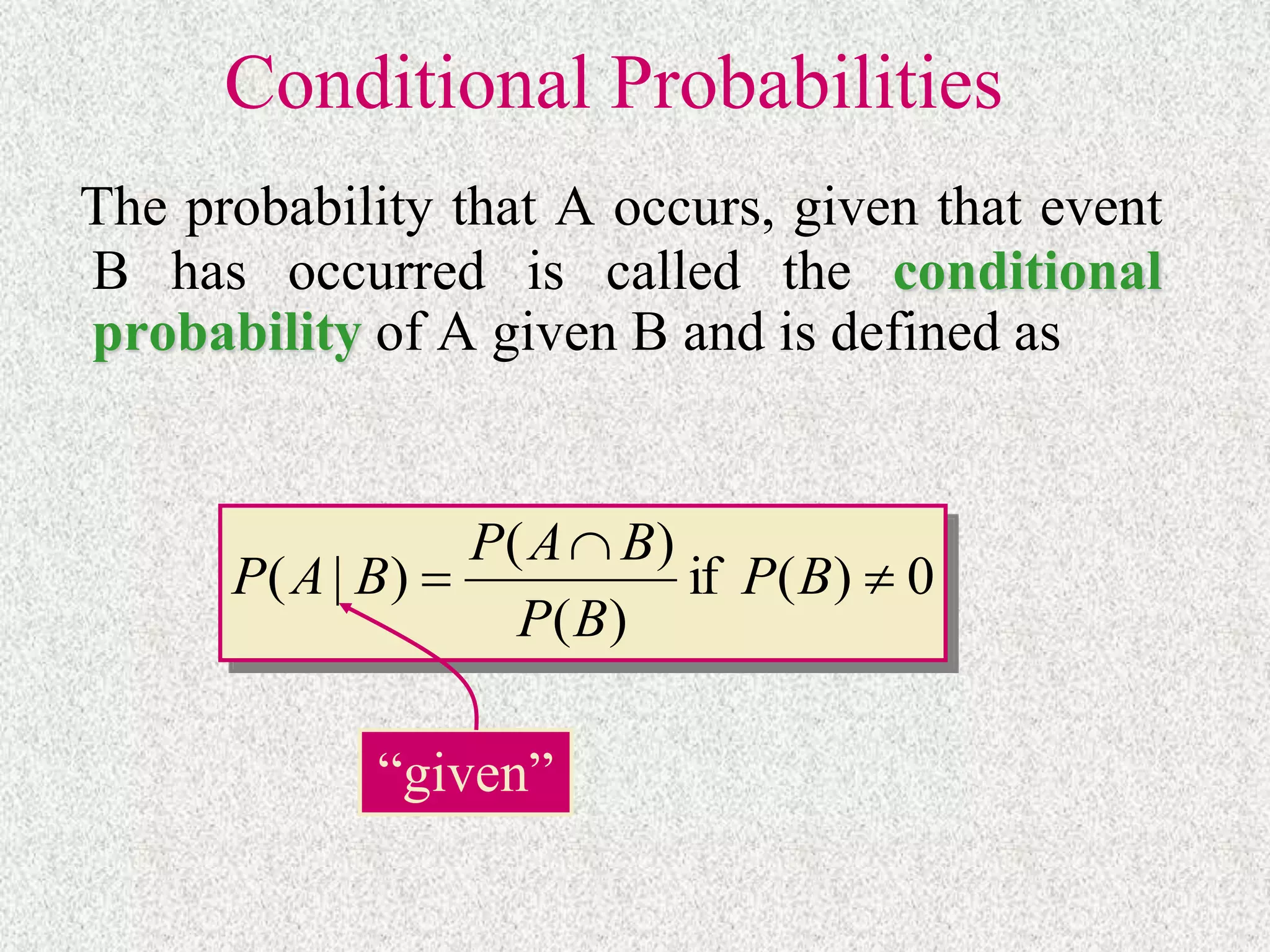

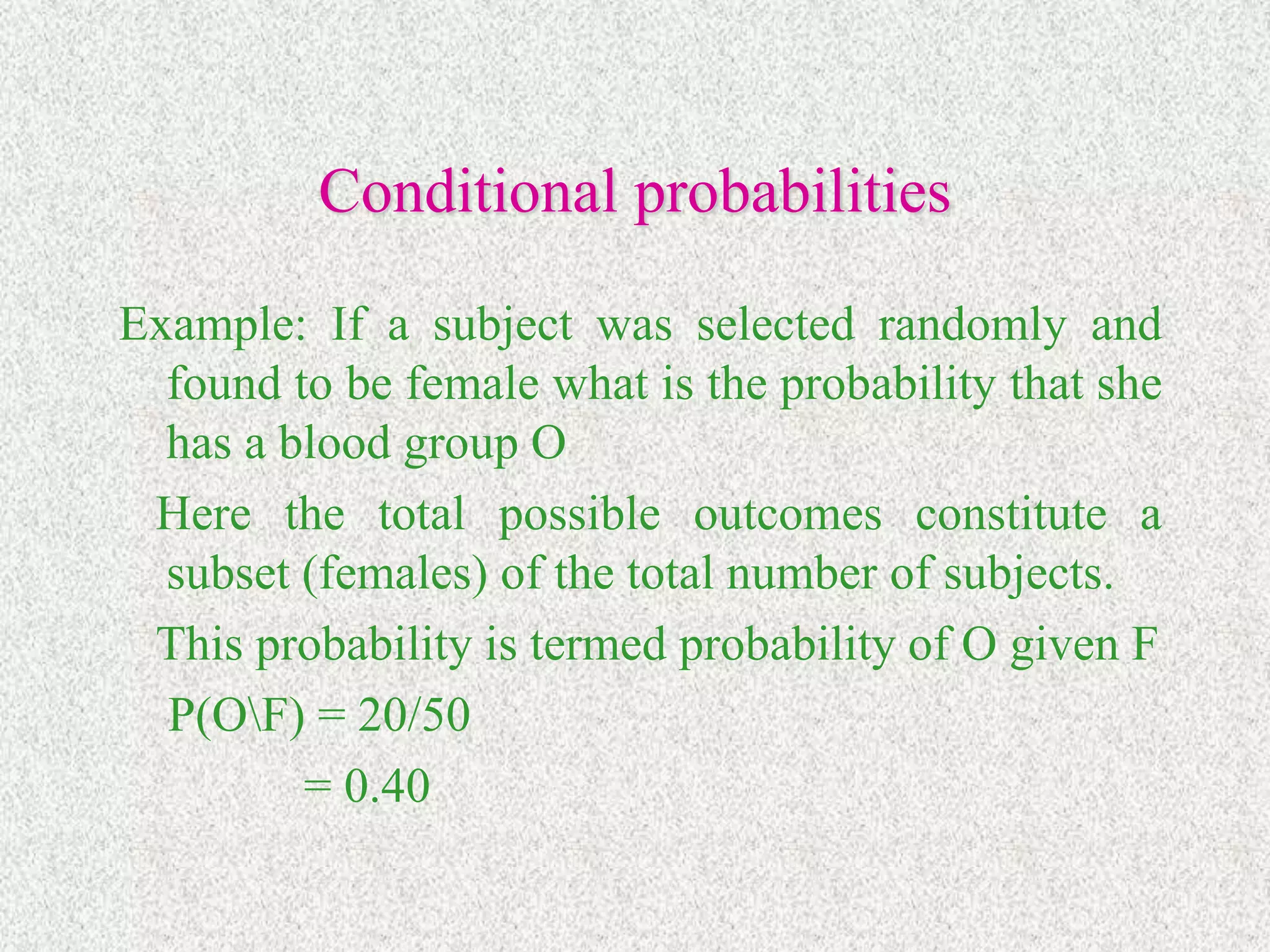

- Complement and conditional probabilities relate the probabilities of events. Independent events do not influence each other's probabilities.