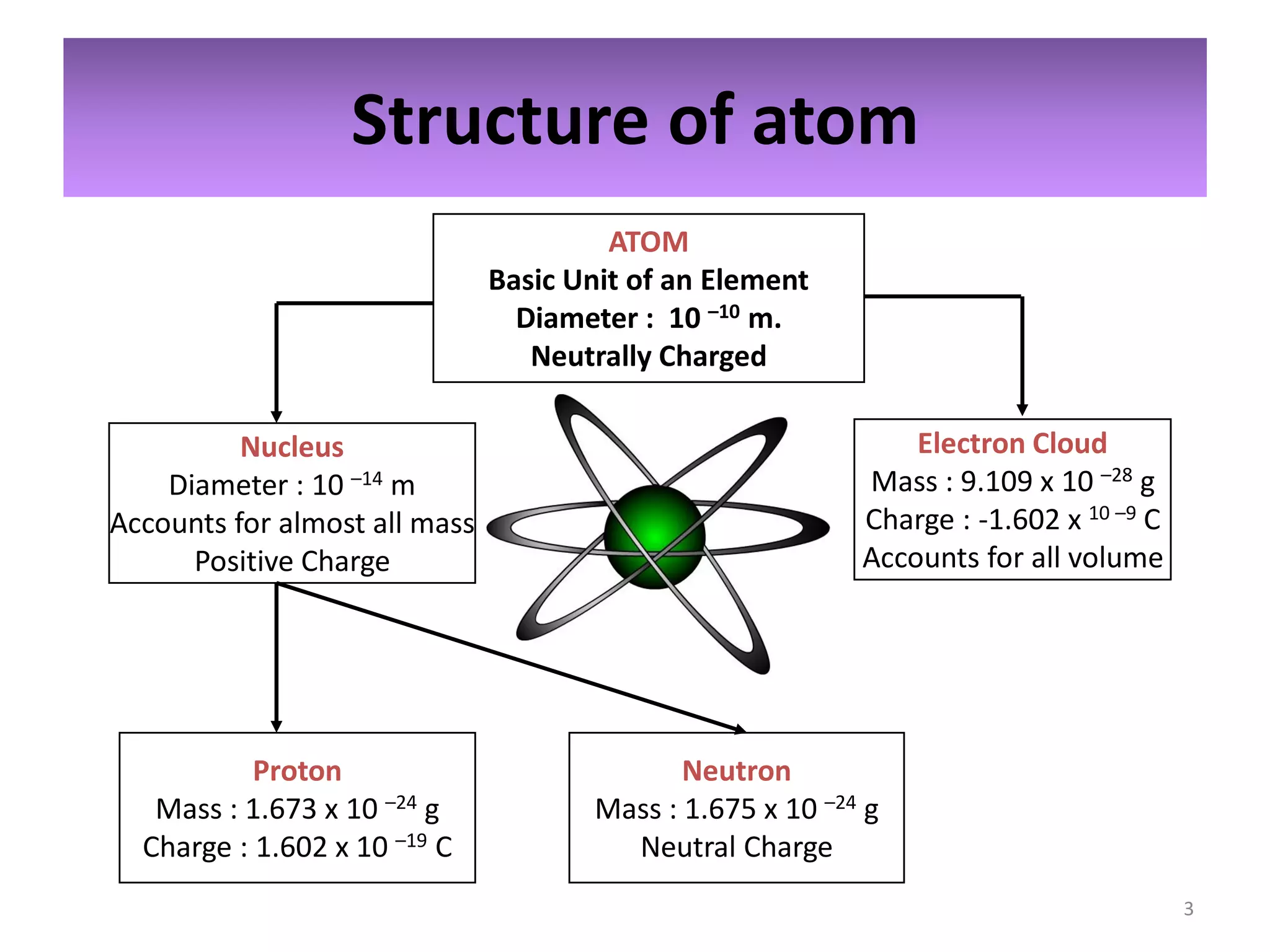

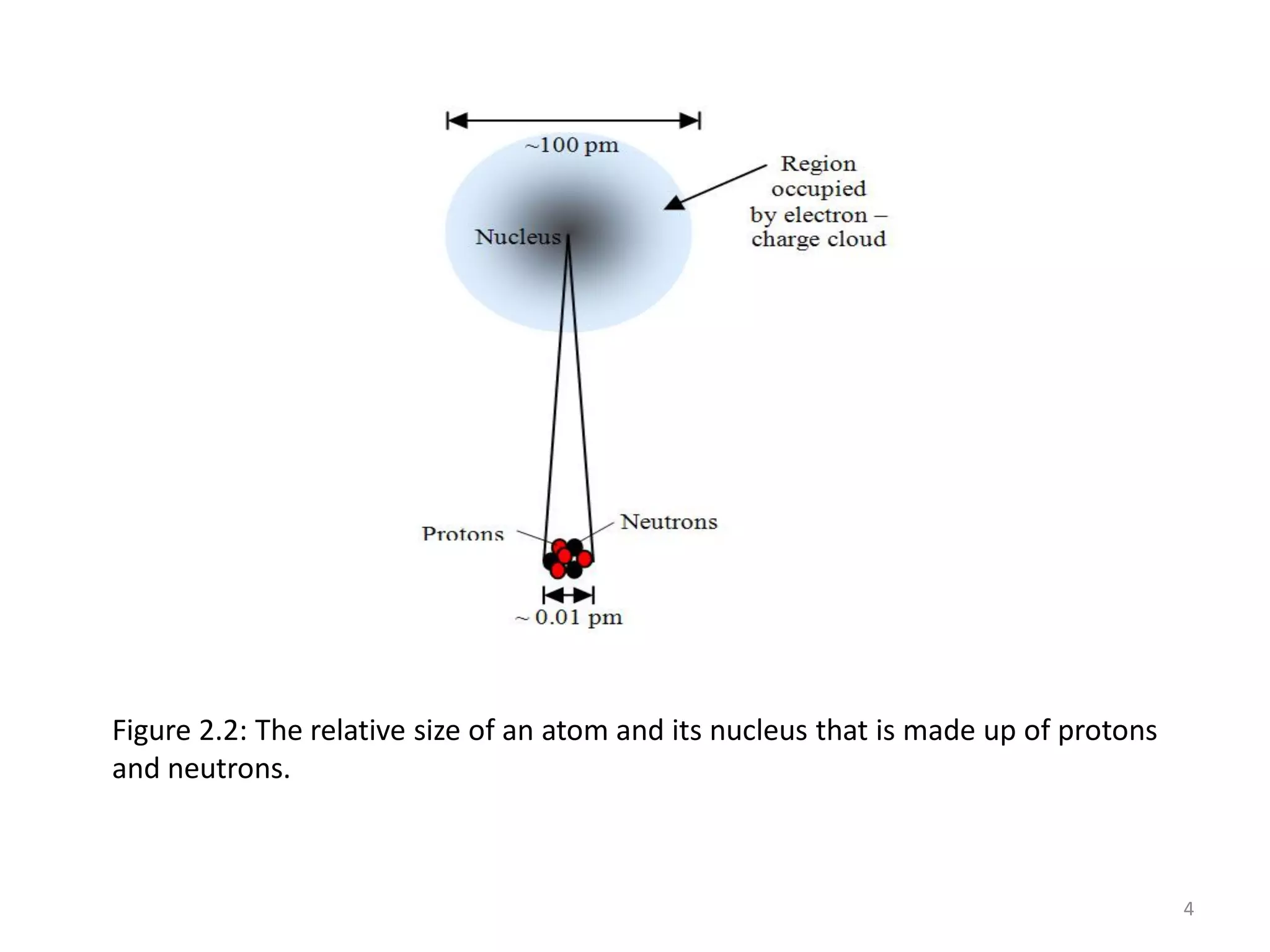

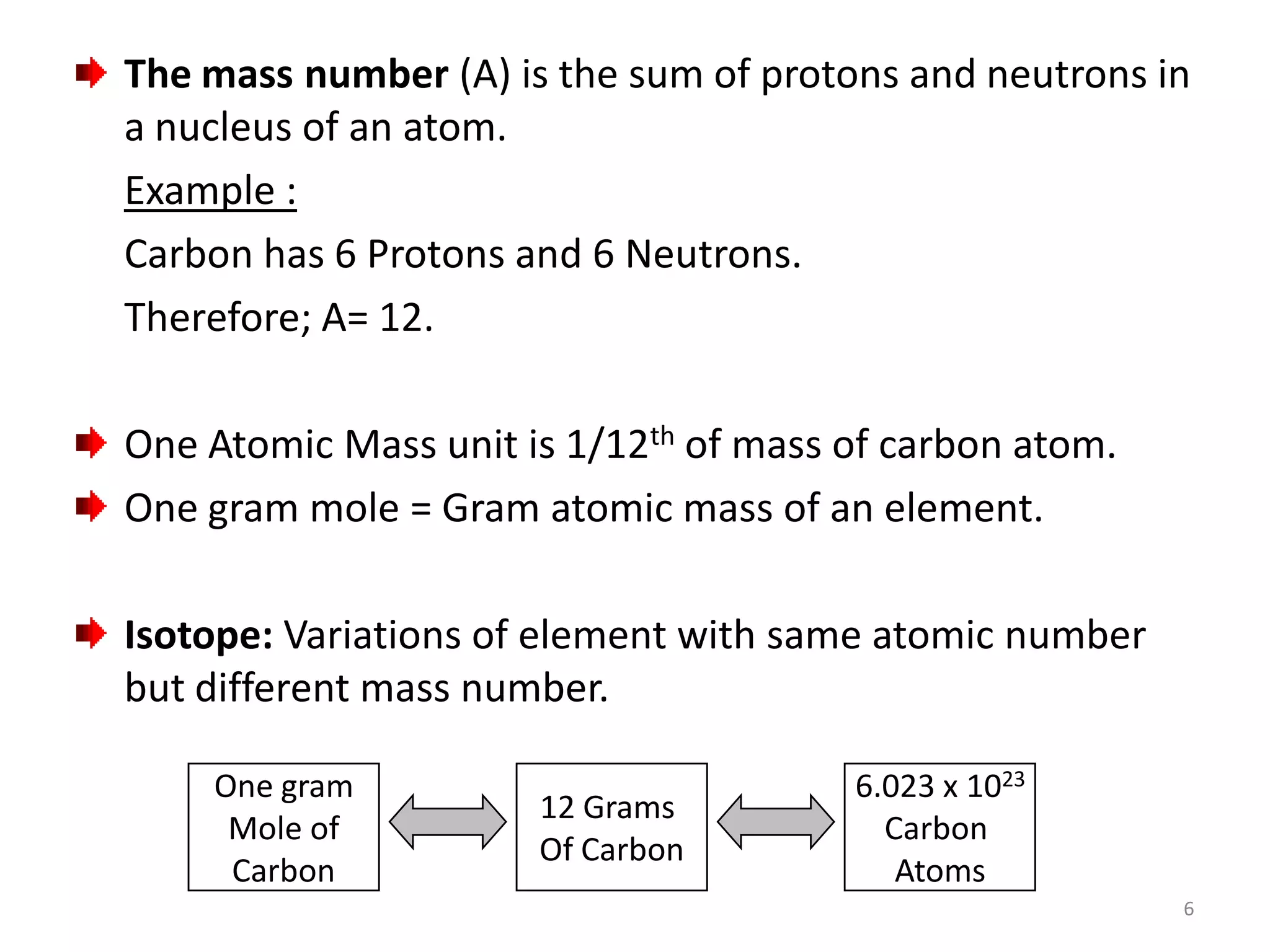

1) The document discusses the history and modern structure of the atomic model, including the discovery of subatomic particles like protons, neutrons, and electrons. It describes the structure of the atom including the nucleus and electron cloud.

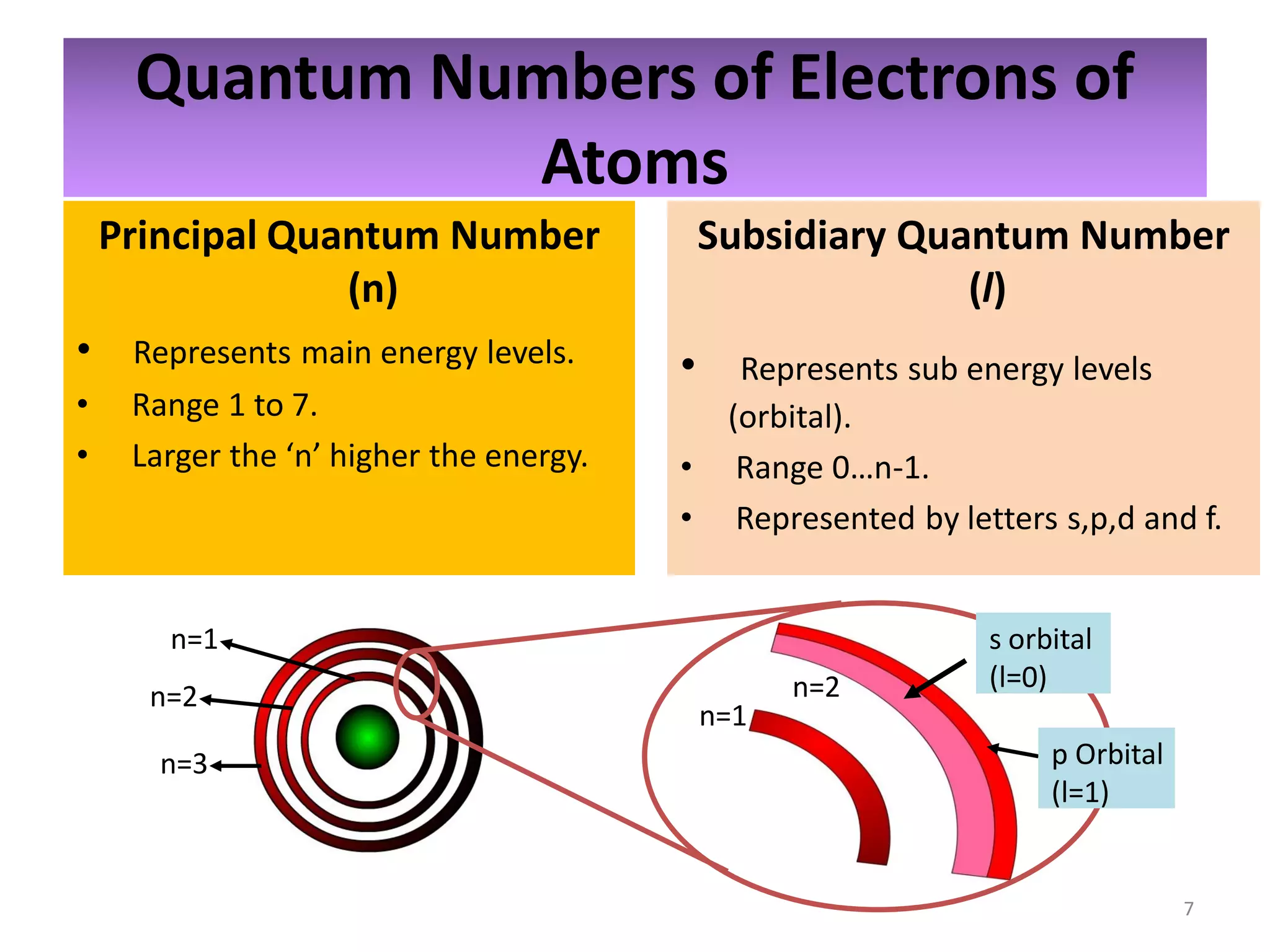

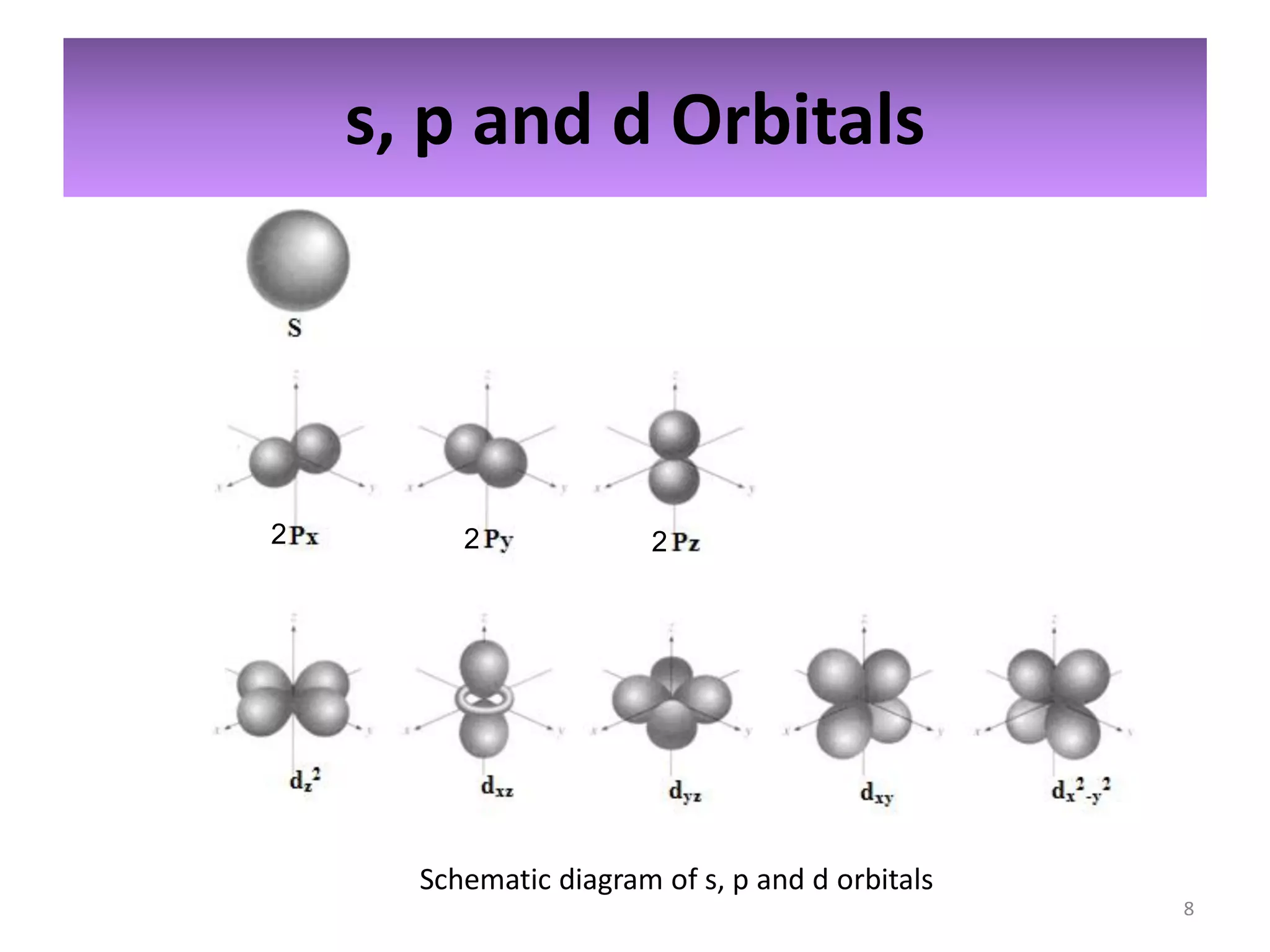

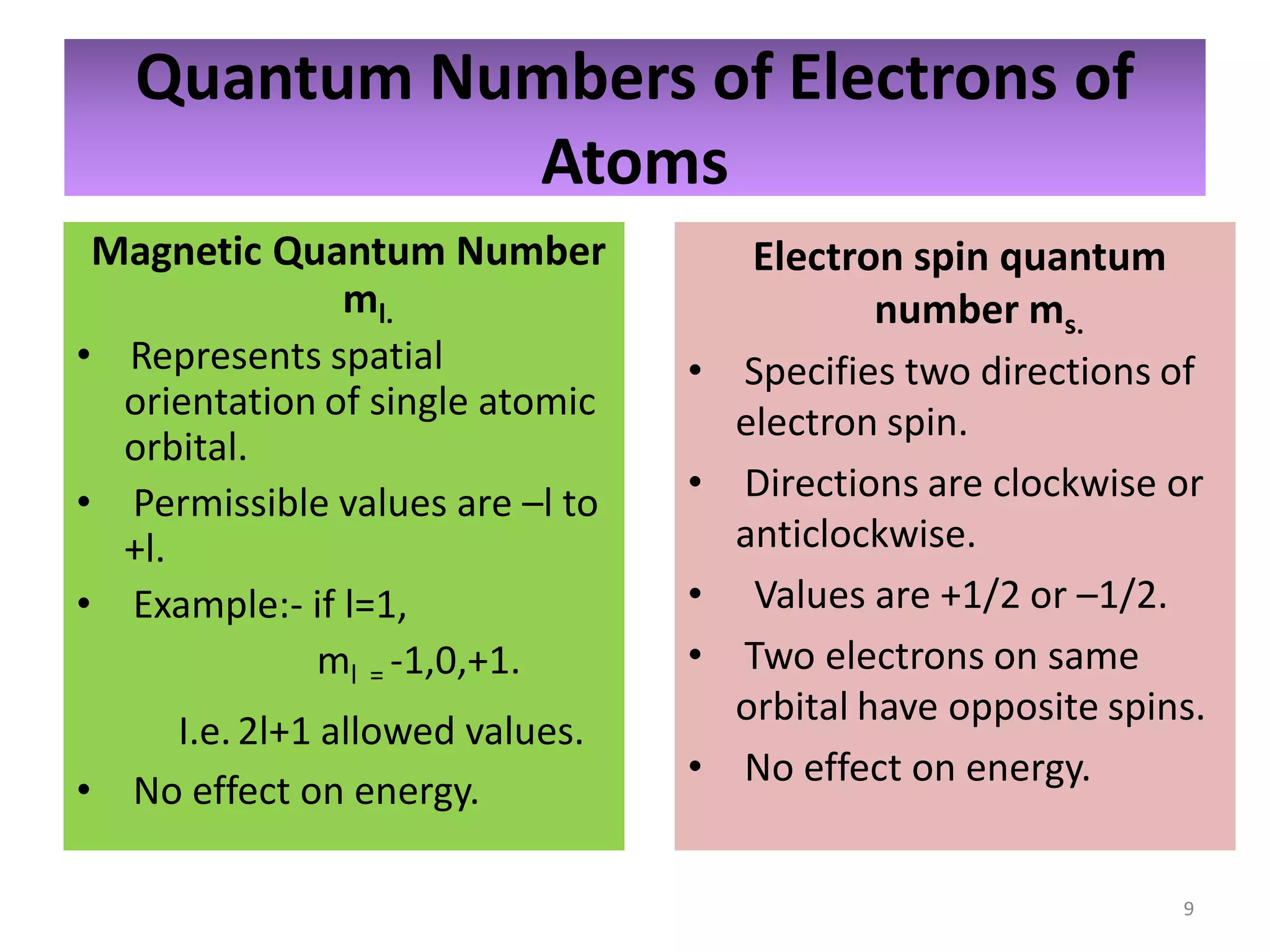

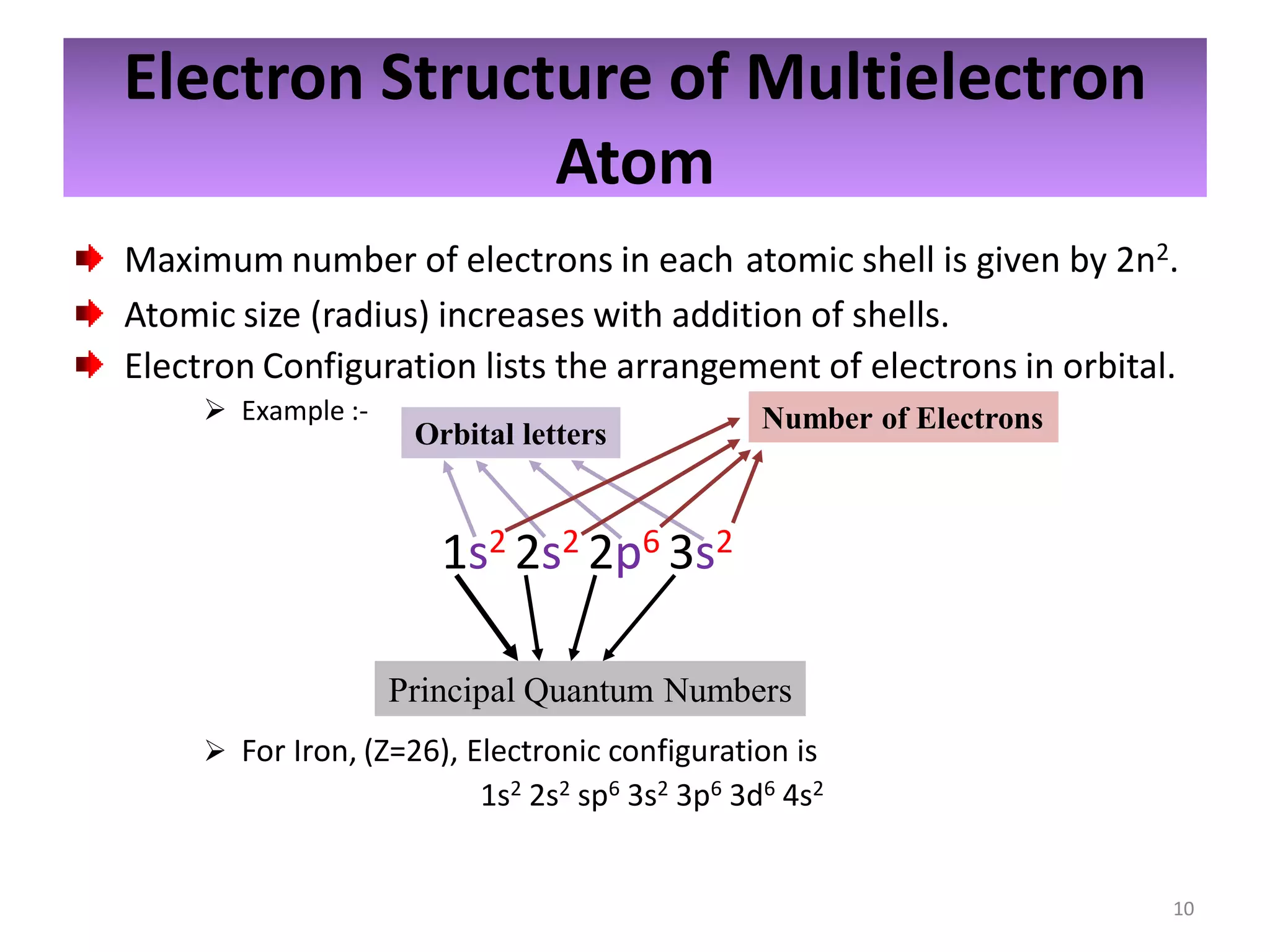

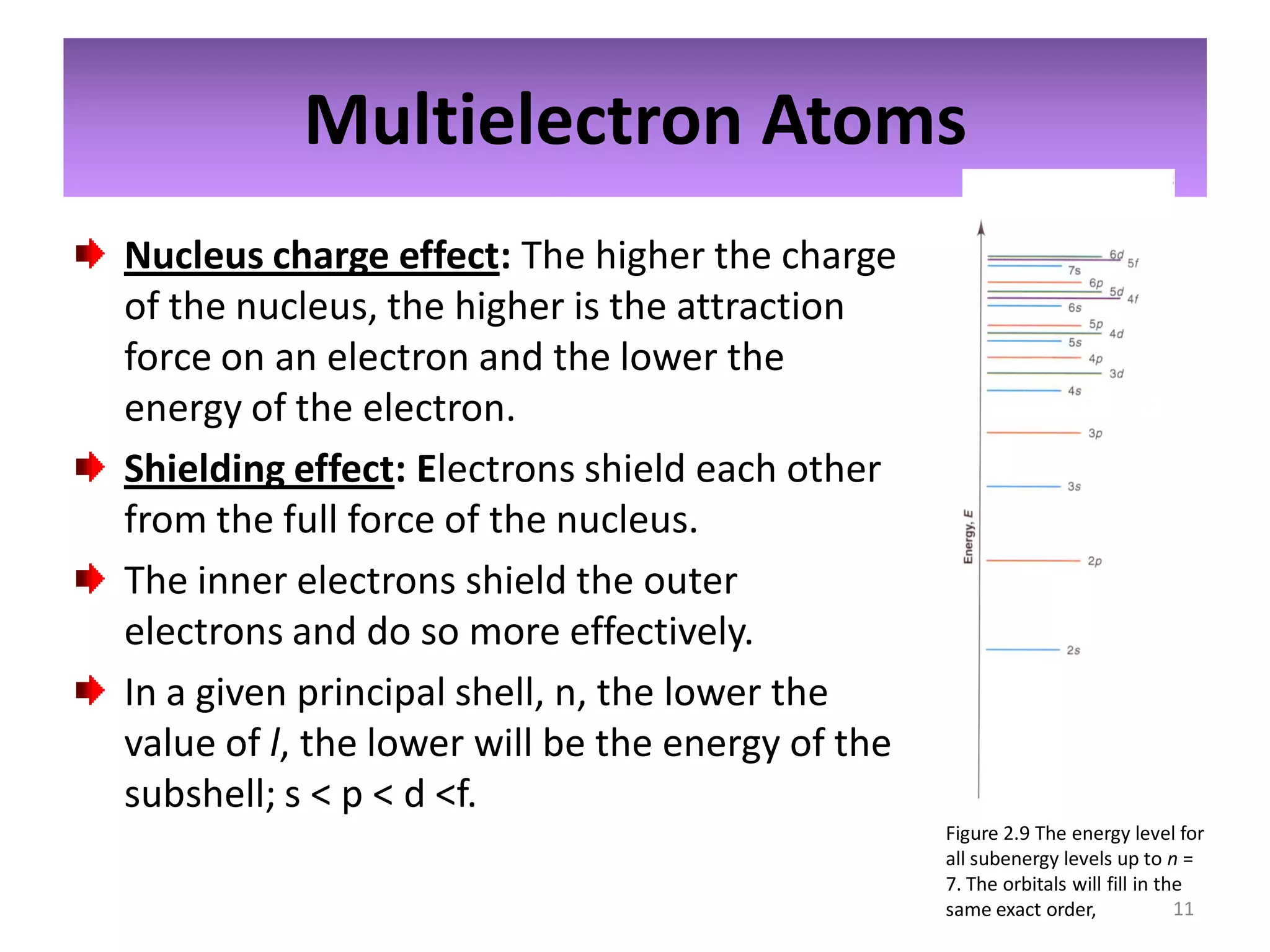

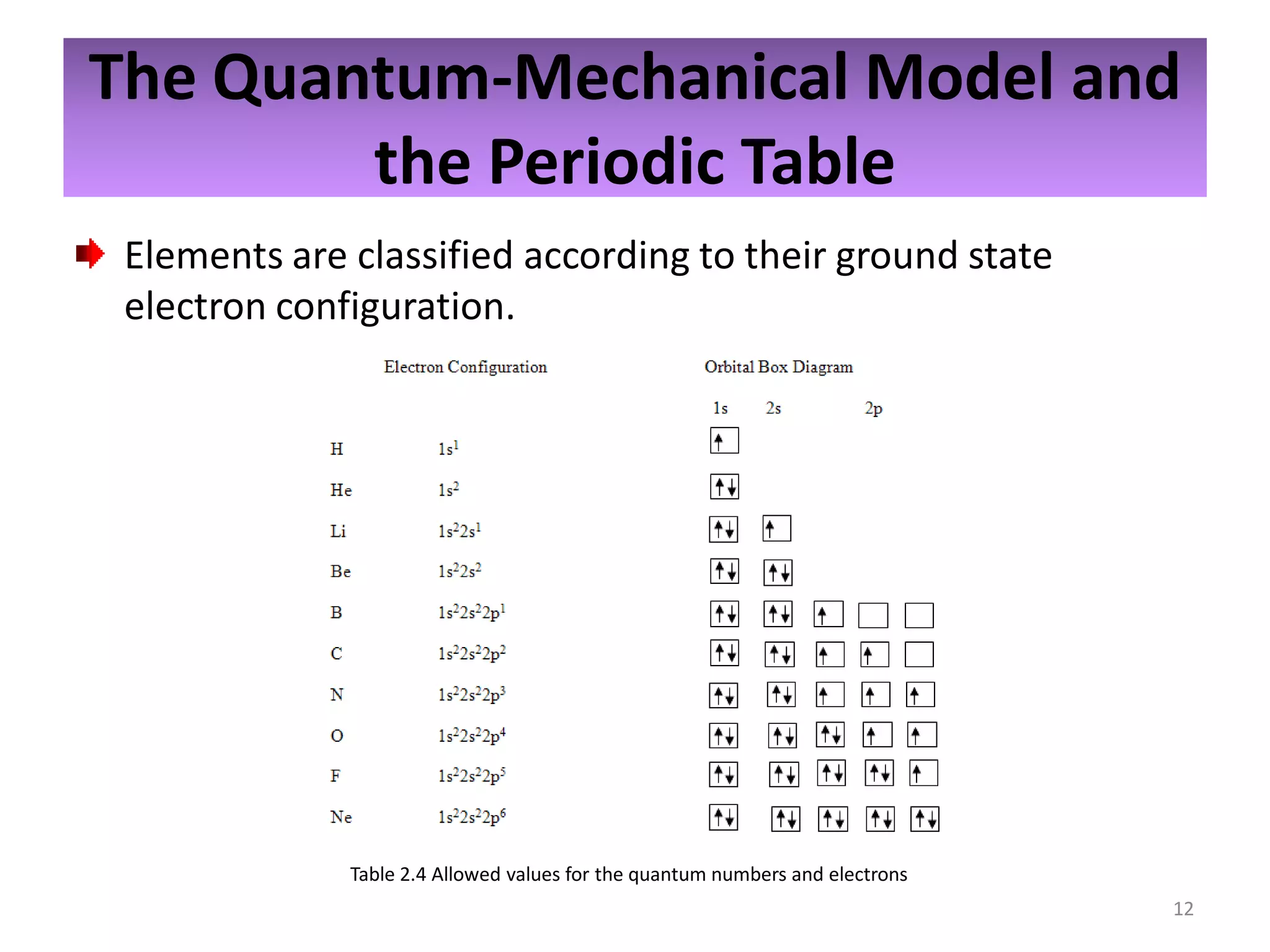

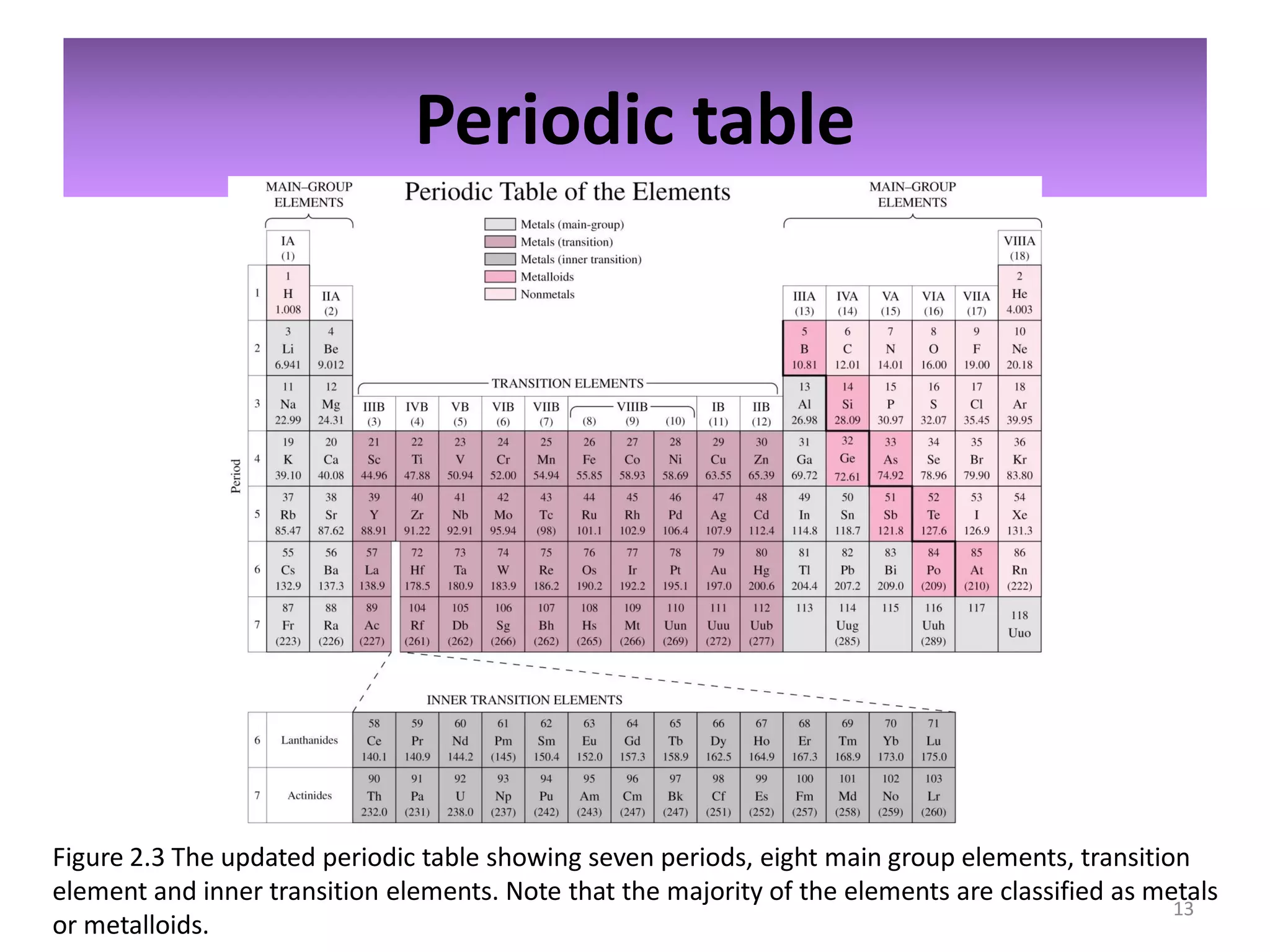

2) Quantum numbers are introduced to describe the allowed energy states of electrons. Electron configuration is used to write out the arrangement of electrons in atoms and relates to an element's position in the periodic table.

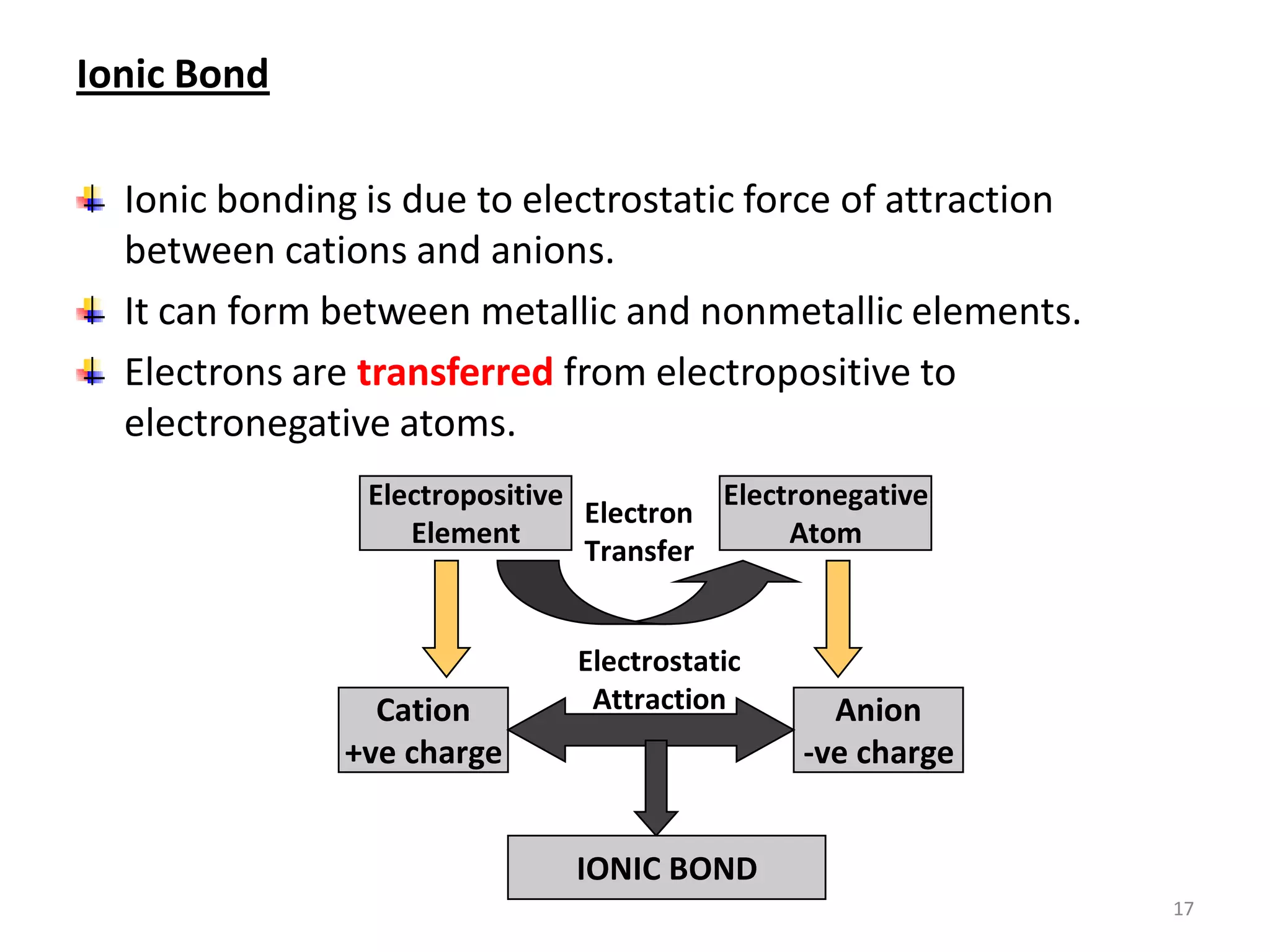

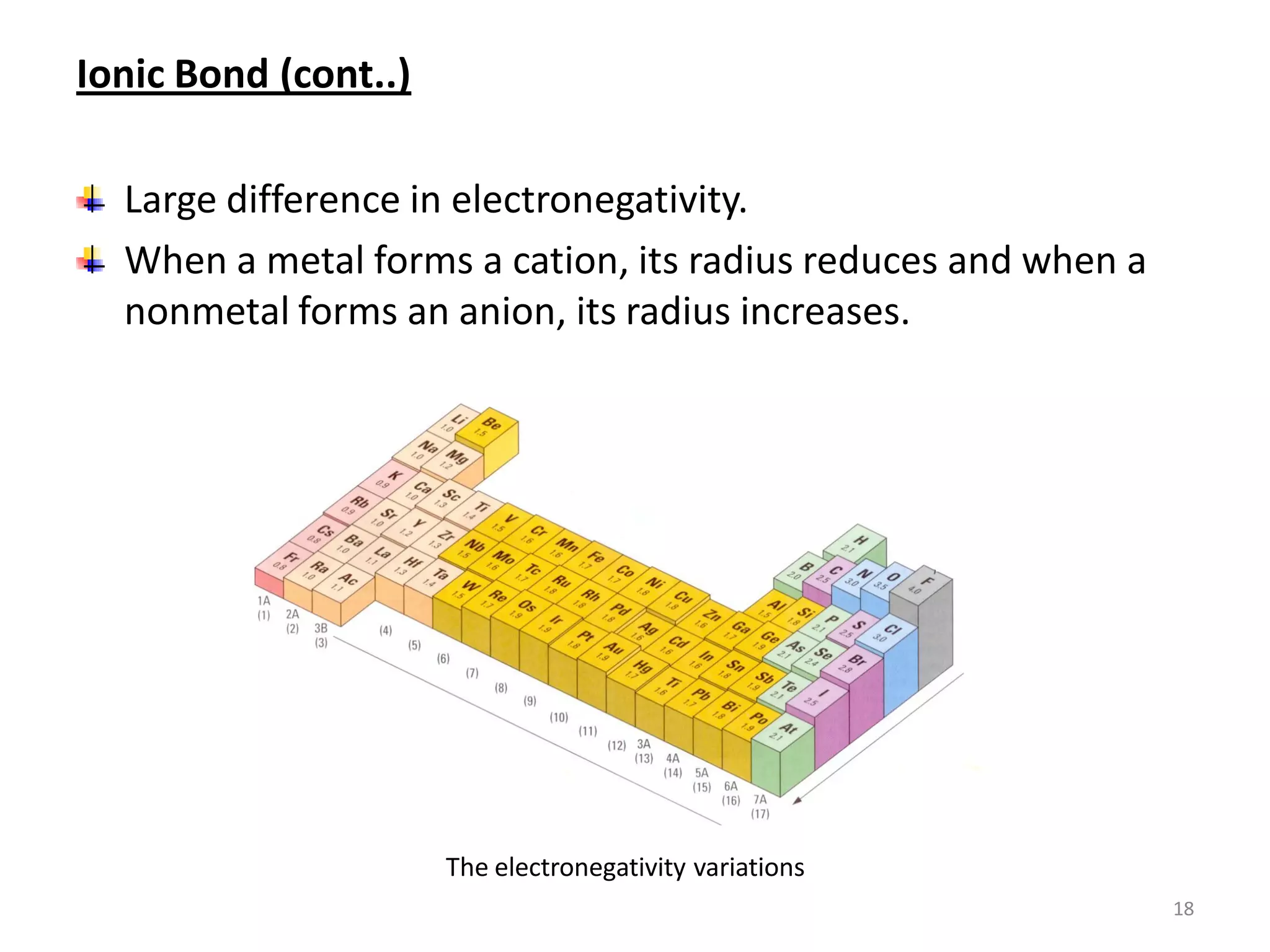

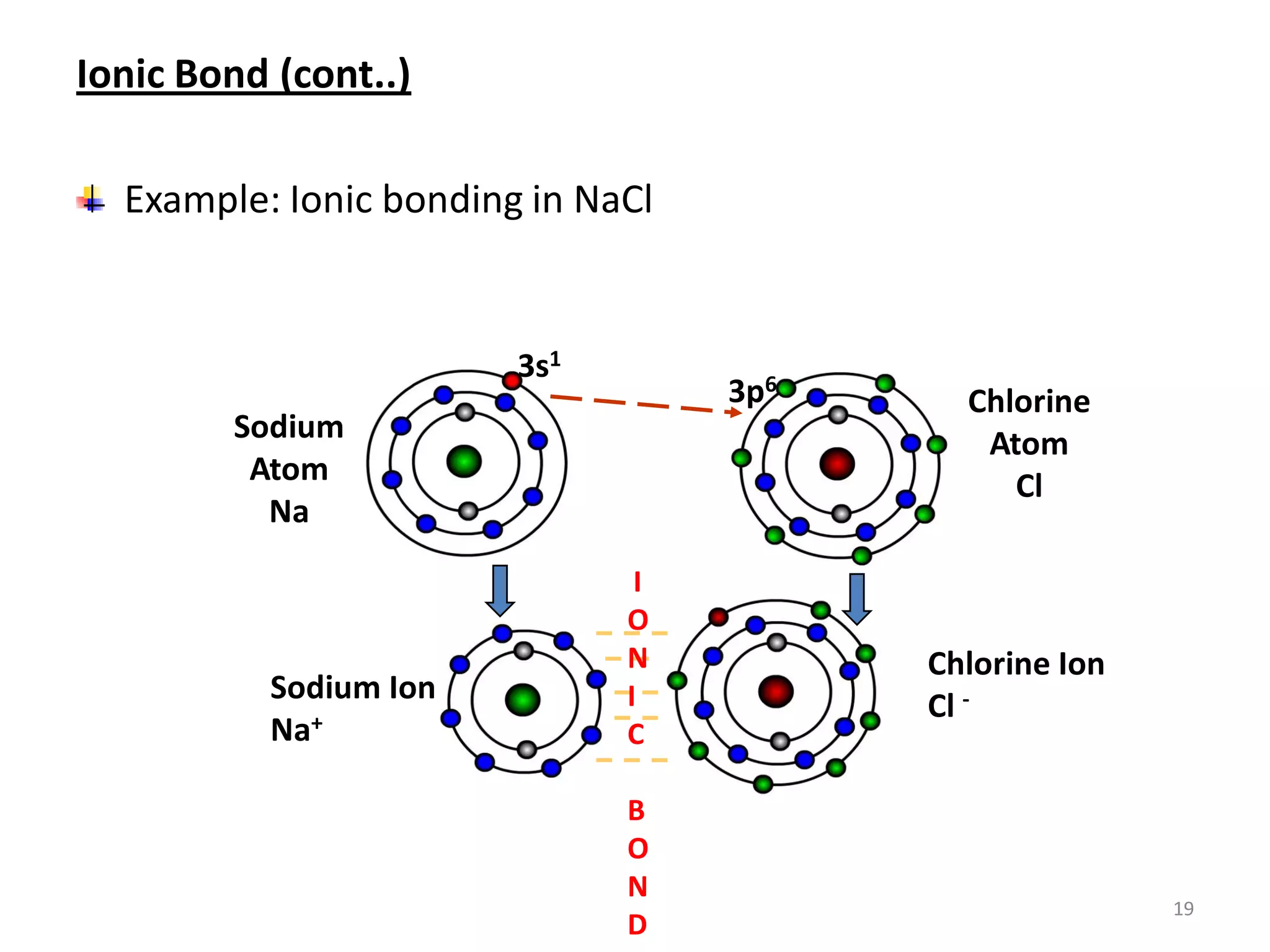

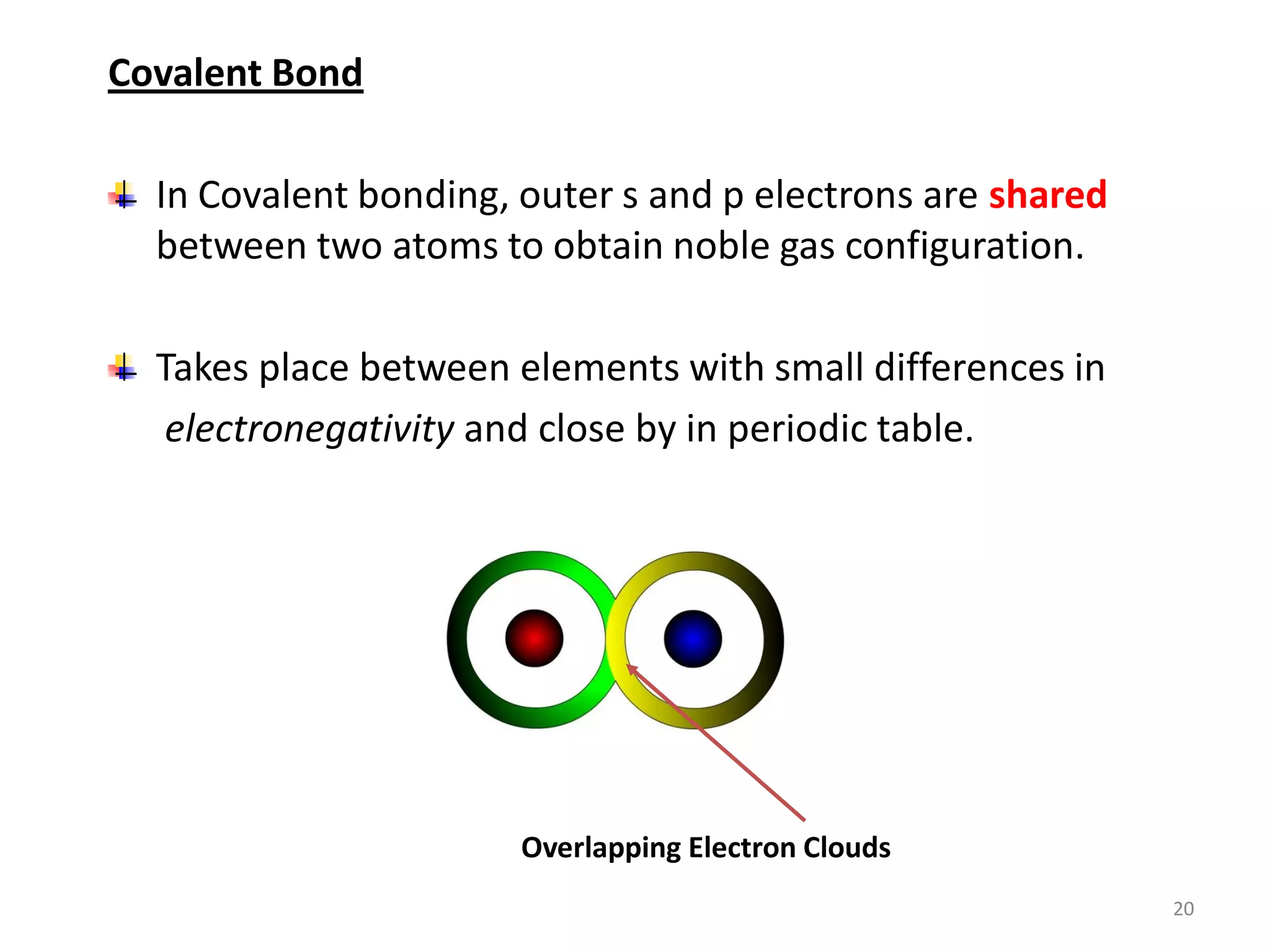

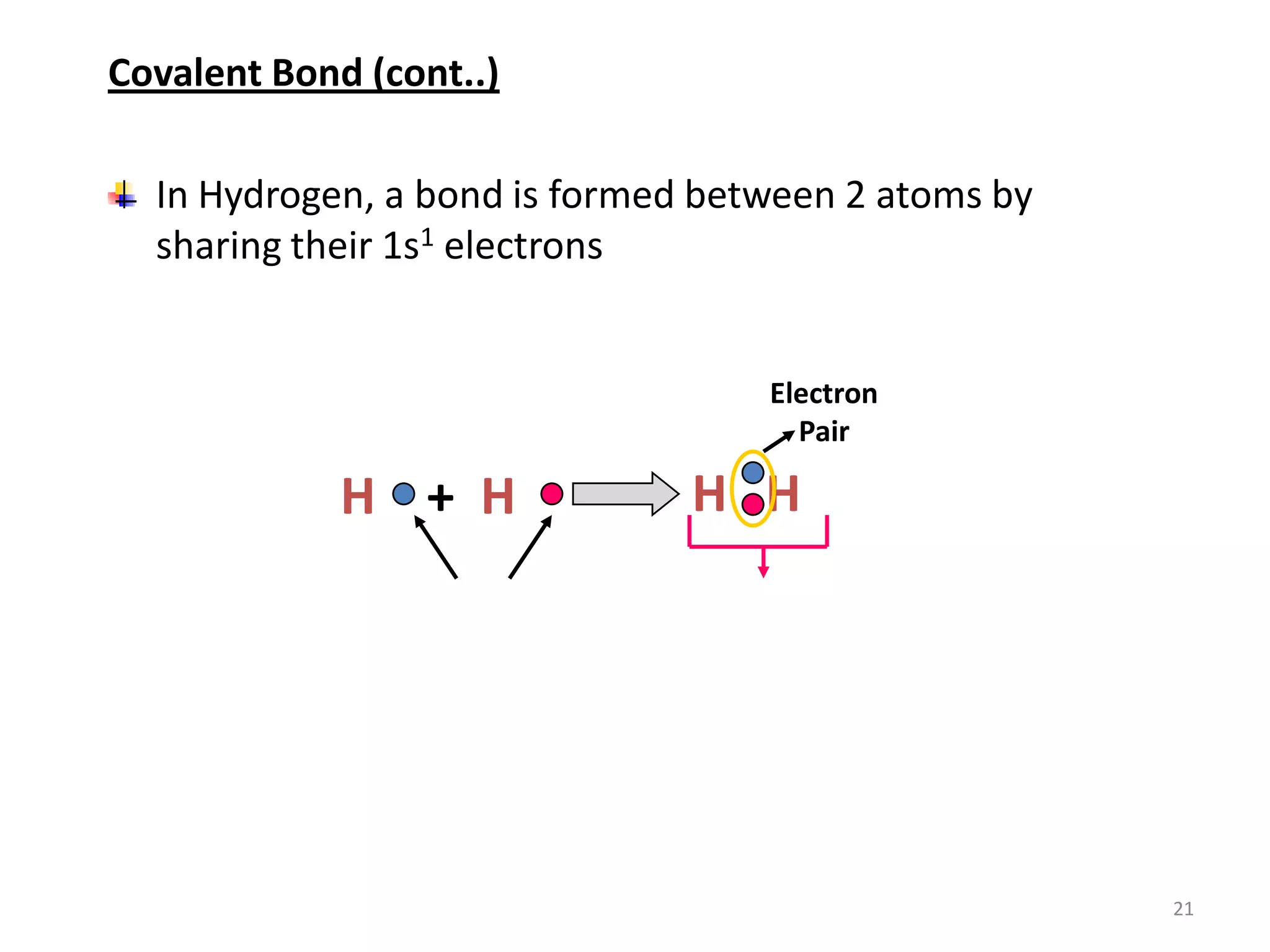

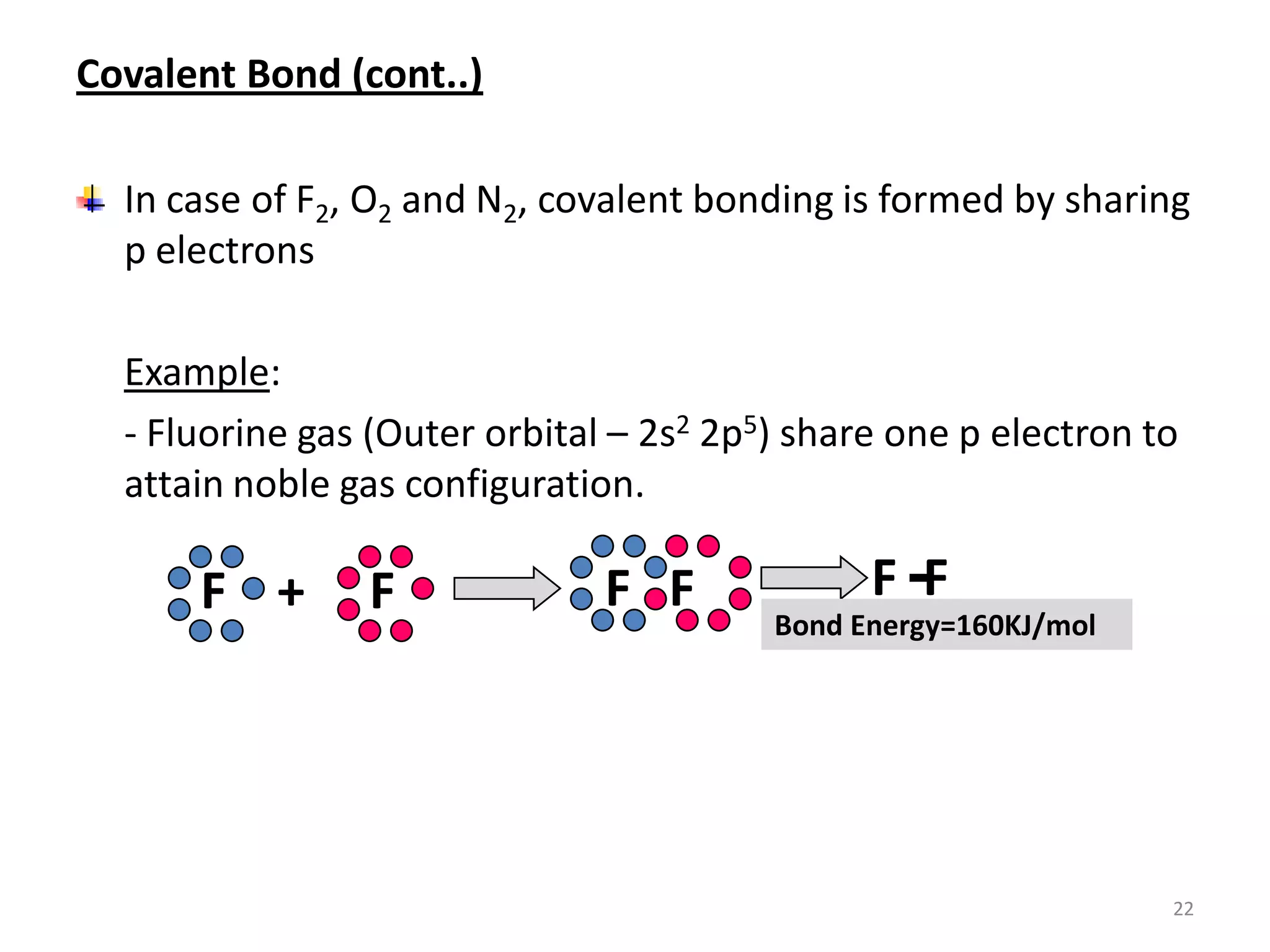

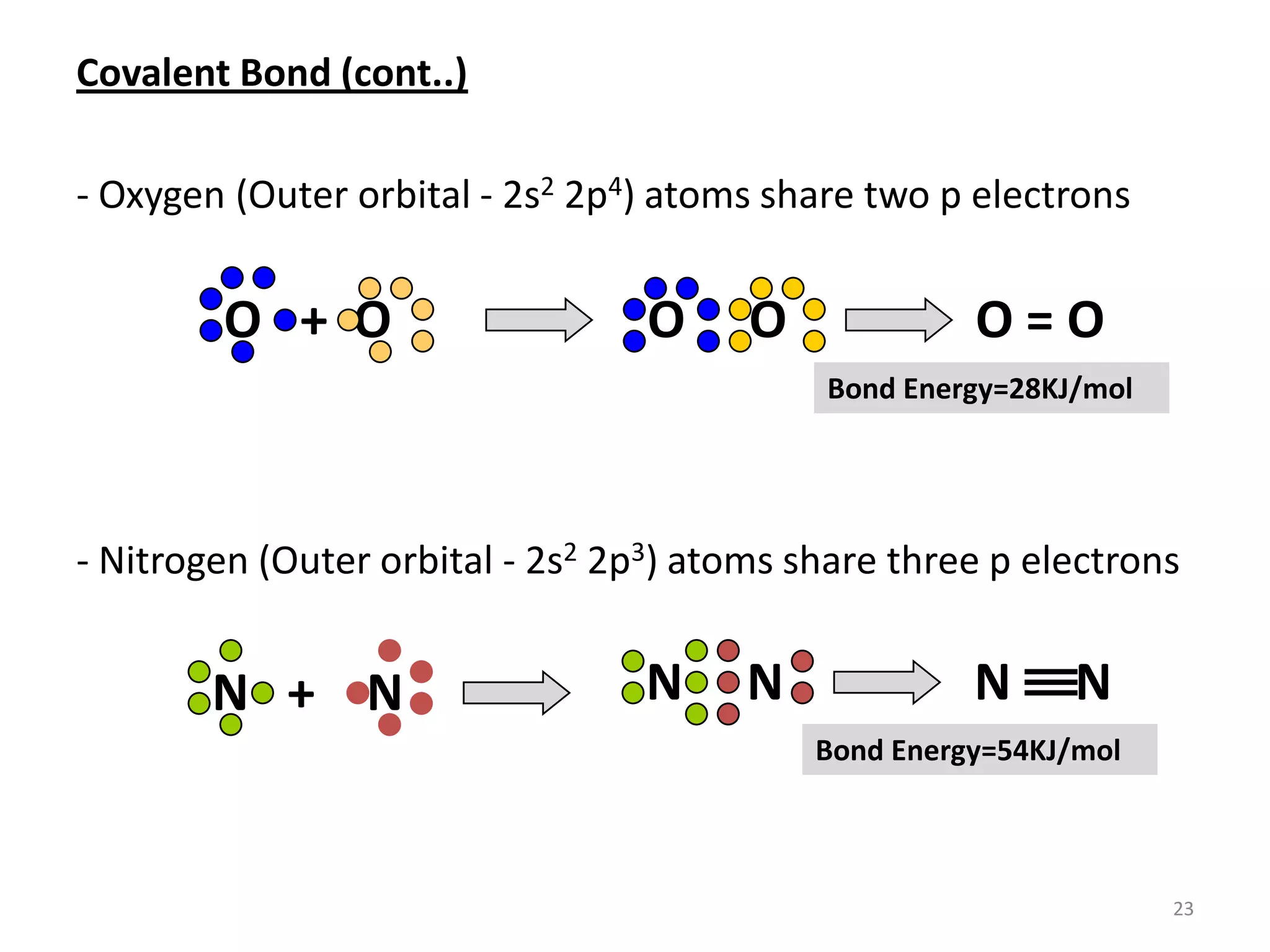

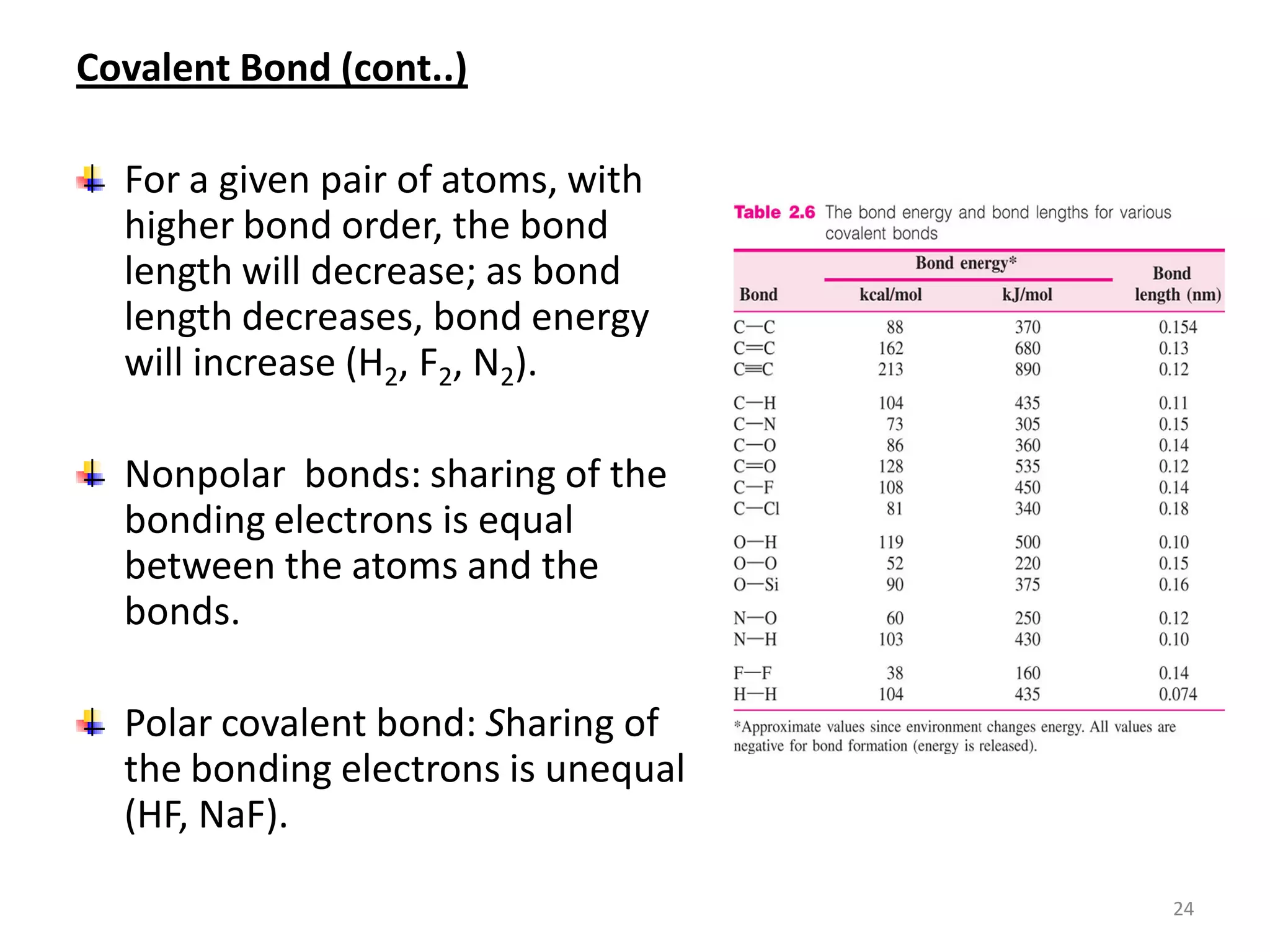

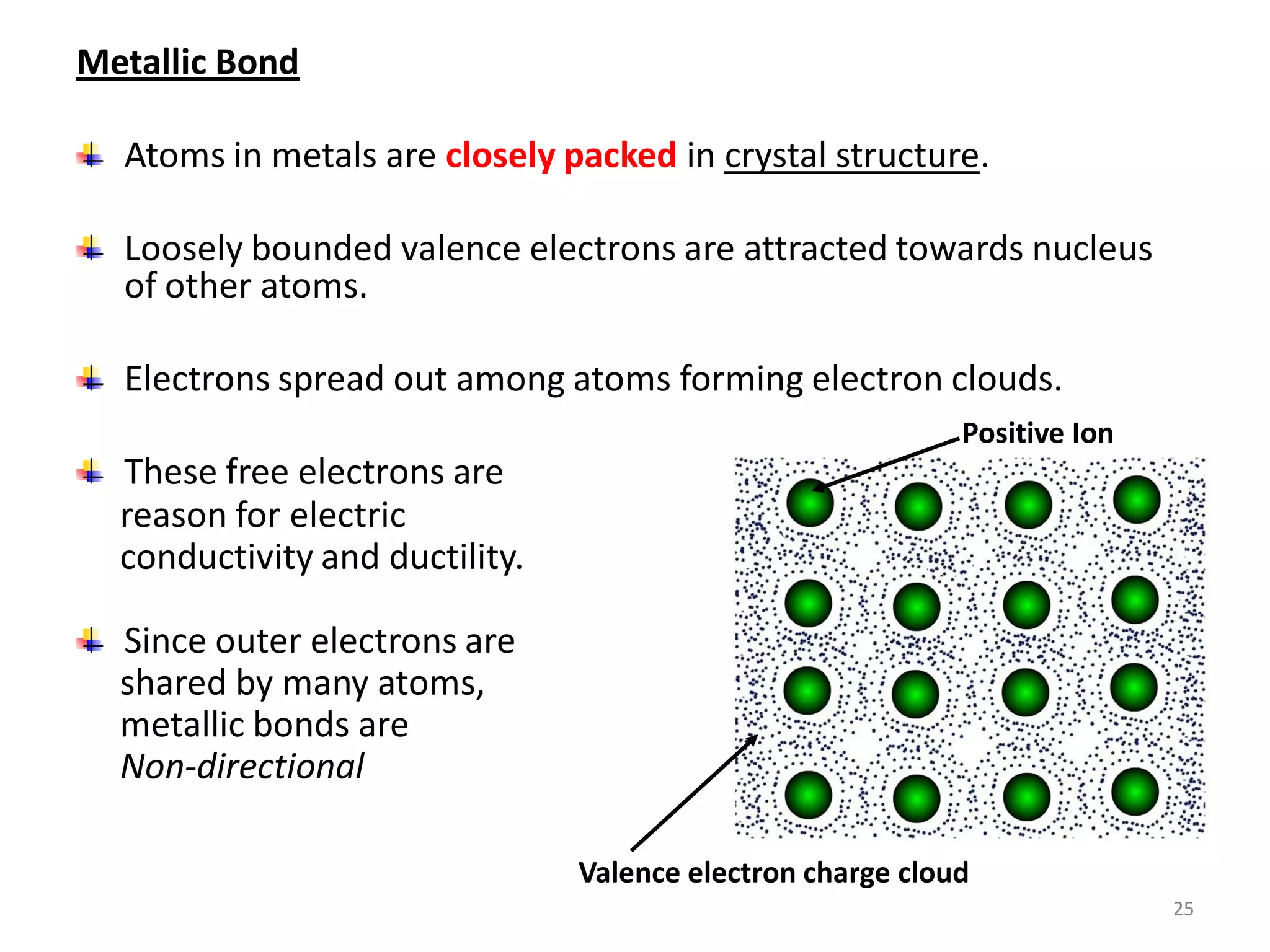

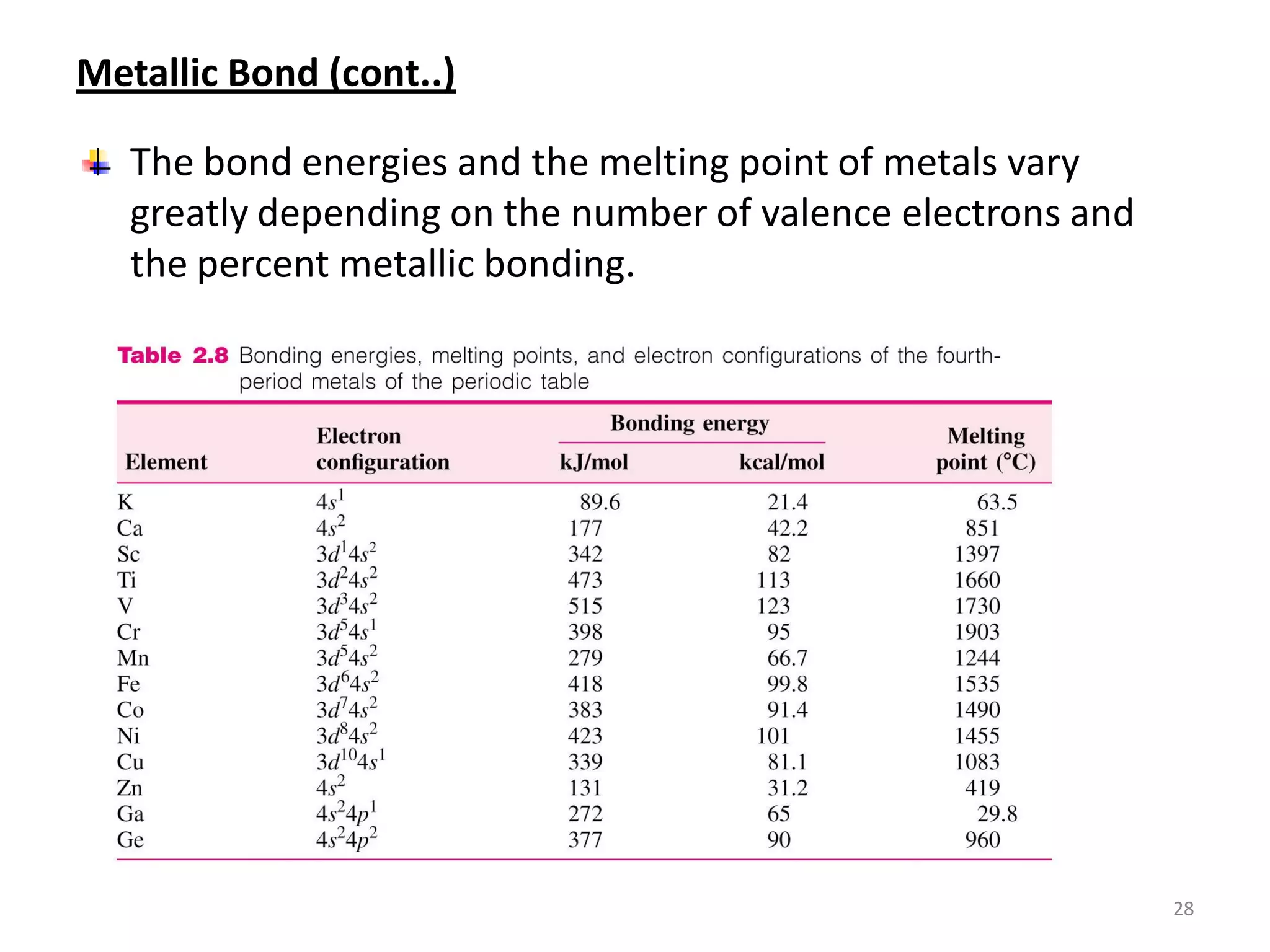

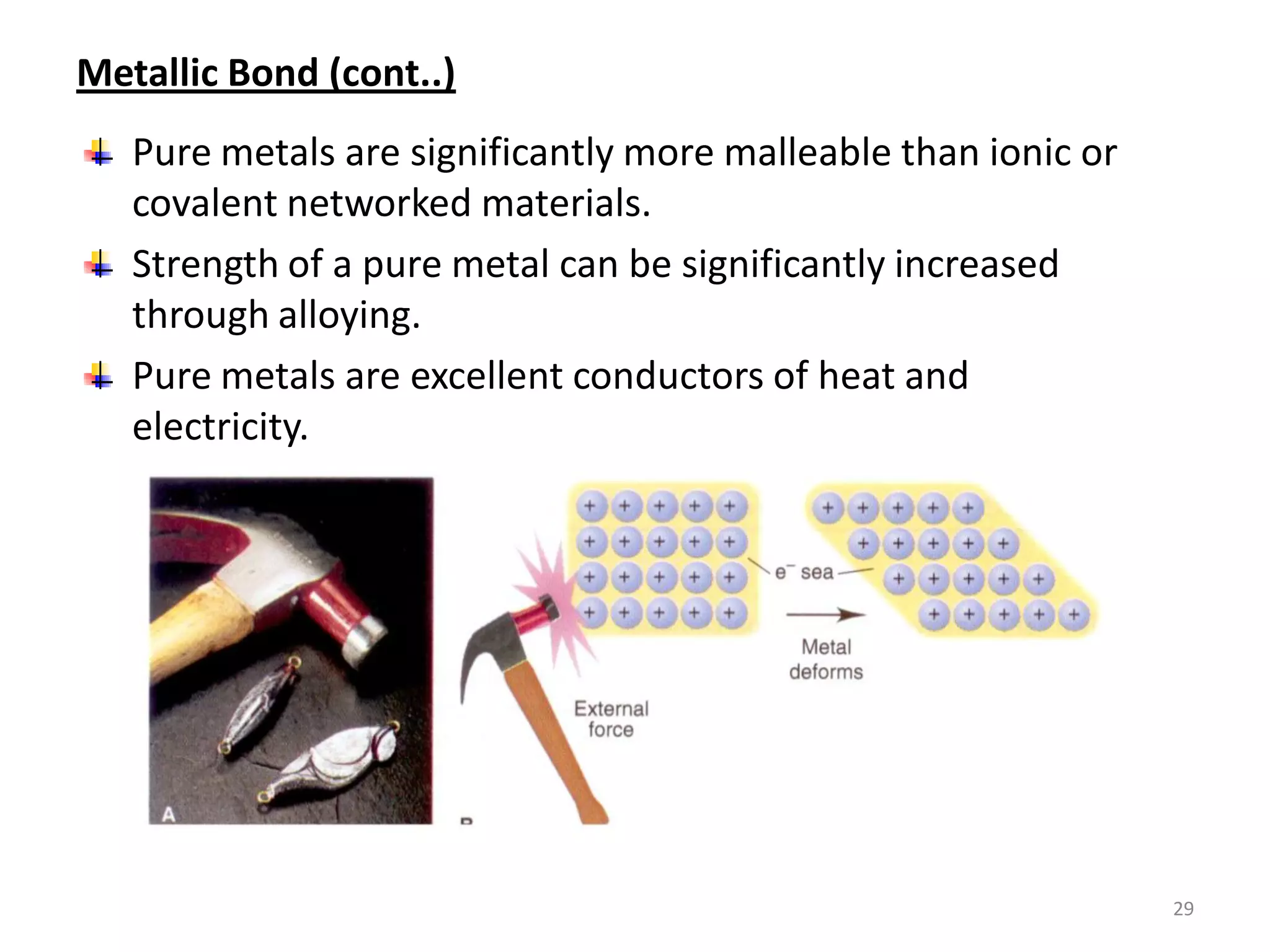

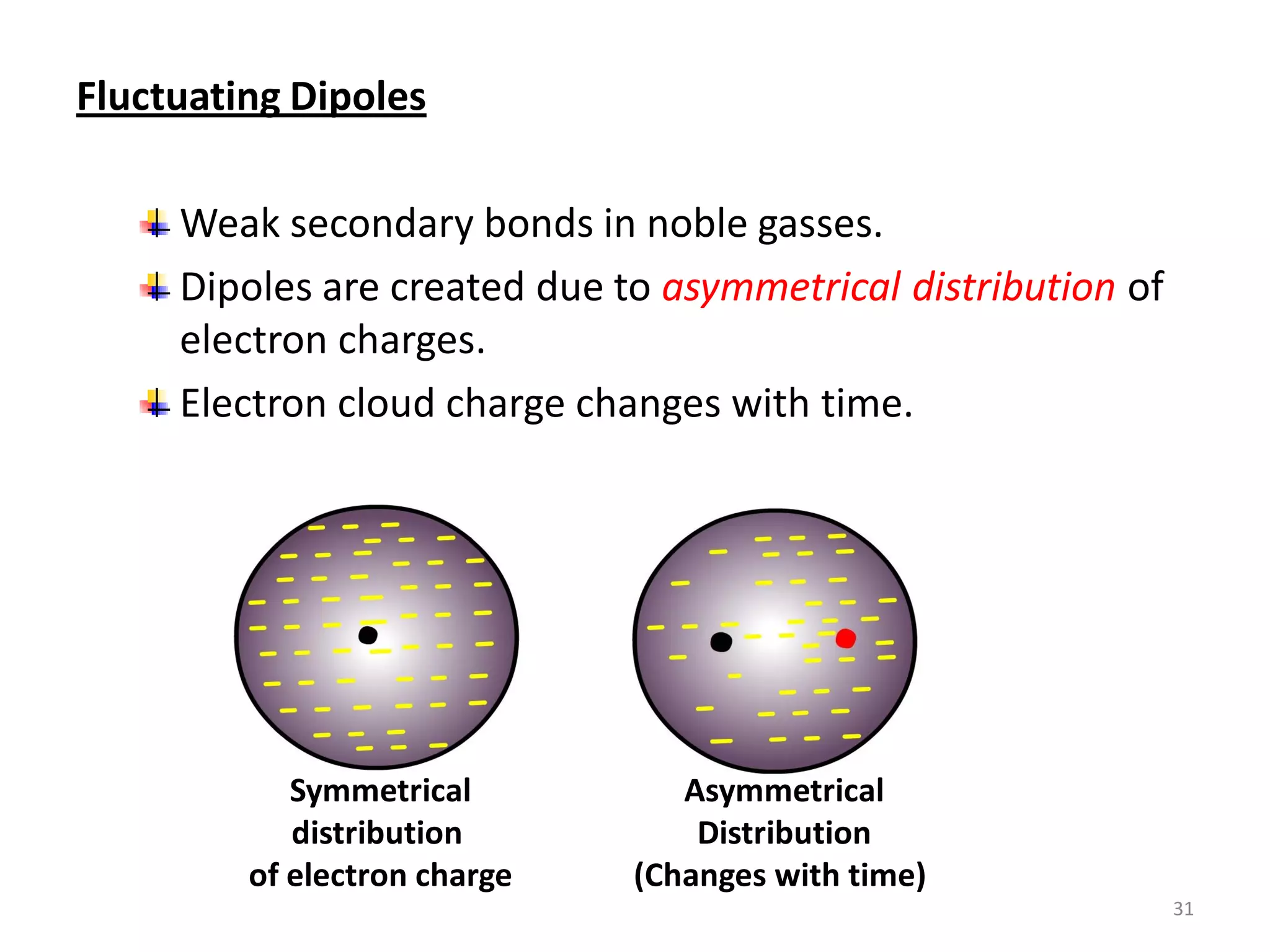

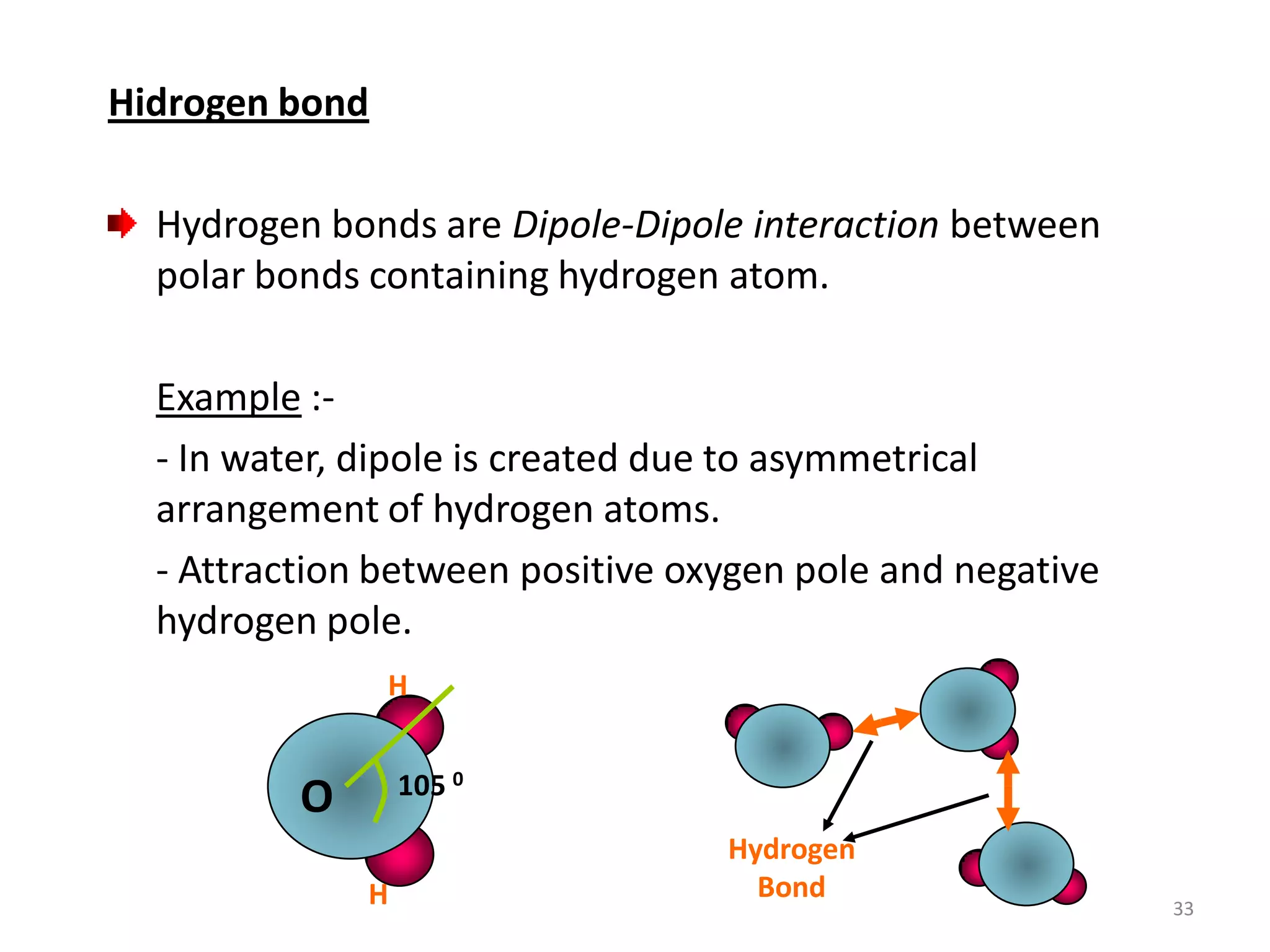

3) Different types of chemical bonds are described including ionic bonds formed by electron transfer, covalent bonds formed by electron sharing, and metallic bonds formed by delocalized electrons in metal crystals. Secondary bonds like hydrogen bonds are also introduced.