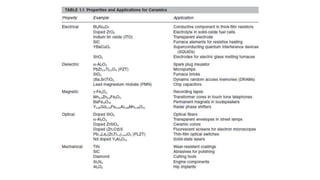

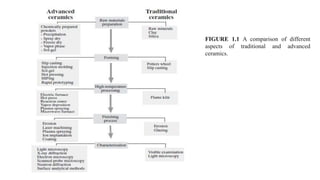

This document provides an overview of ceramic materials. It defines ceramics as nonmetallic inorganic solids made through processes like shaping, drying, and firing. Ceramics exhibit properties like brittleness at room temperature due to their ionic and covalent bonding, but some can deform at high temperatures. The document discusses how ceramics are classified and notes exceptions to general rules due to their wide range of properties and applications in different fields.

![• Reducing cost of the final product

• Improving reliability

• Improving reproducibility

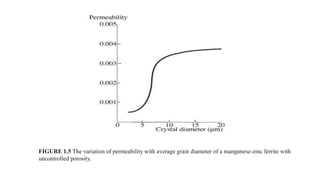

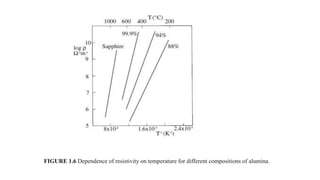

• Electronic ceramics include barium titanate (BaTiO3), zinc oxide (ZnO), lead

zirconate titanate [Pb(ZrxTi1−x)O3], aluminum nitride (AlN), and HTSCs.

• They are used in applications as diverse as capacitor dielectrics, varistors,

microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), substrates, and packages for integrated

circuits.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ceramicmaterials-210212072224/85/Ceramic-materials-28-320.jpg)