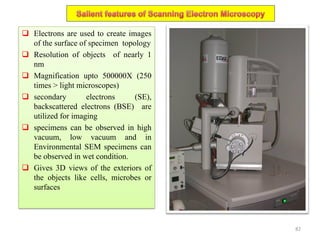

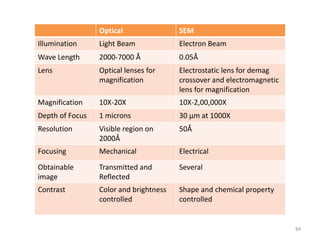

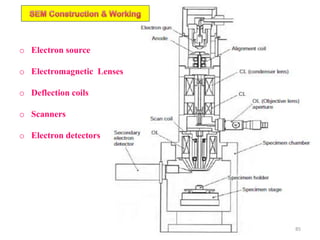

The document contains lecture notes on materials characterization, detailing essential topics such as optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray diffraction. It emphasizes the importance of accurately measuring the physical and chemical properties of materials for structure-property correlation. Additionally, it includes information on crystallography, crystal structure definitions, and various microscopy techniques.

![Crystallographic Directions

A crystallographic direction is defined as a line between 2 points, or a vector.

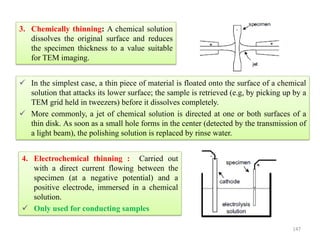

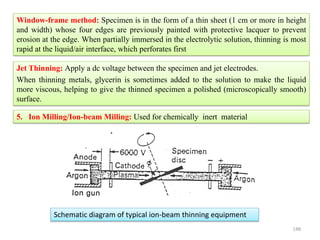

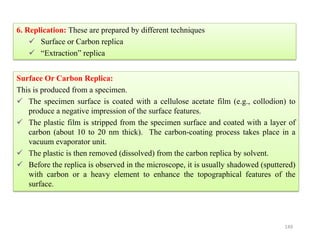

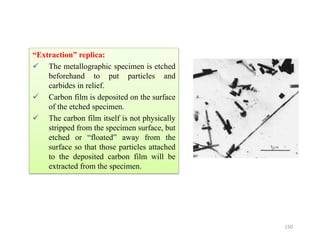

The following steps are utilized in the determination of the 3 directional indices:

A vector of convenient length is positioned such that it passes through the origin of

the coordinate system.

Any vector may be translated throughout the crystal lattice without alteration, if

parallelism in maintained.

The length of the vector projection on each of the 3 axes is determined; these are

measured in terms of the unit cell dimensions a, b, and c.

These 3 numbers are multiplied or divided by a common factor to reduce them to the

smallest integer values.

The 3 indices (not separated by commas) are enclosed in square brackets: [uvw]

where u, v, and w integers correspond to the reduced projection along the x, y, and z

axes, respectively.

A vector r passing from the origin to a lattice

point can be written as:

r = r1 a + r2 b + r3 c Where, a, b, c → basic

vectors

Note their length is not 1 unit! (like for the basis

vectors of a coordinate axis).

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-11-320.jpg)

![[010]

[100]

[001]

[110]

[101]

[011]

[110] [111]

Important directions in 3D represented by Miller Indices (cubic lattice)

Face diagonal

Body diagonal

X

Y

Z

Memorize these

116](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-12-320.jpg)

![[+ + -] [+ - -]

[+ - +]

[- - +][- + +]

[+ + +]

[- - -][- + -]

If you have confusion while selecting origin in negative indices refer this figure

Possible coordinates in 3D

X

Y

Z

117](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-13-320.jpg)

![Family of directions

Index Members in family for cubic lattice Number

<100> 3 x 2 = 6

<110>

6 x 2 =

12

<111> 4 x 2 = 8

Symbol

Alternate

symbol

[ ] → Particular direction

< > [[ ]] → Family of directions

[100],[100],[010],[010],[001],[001]

[110],[110],[110],[110],[101],[101],[101],[101],[011],[011],[011],[011]

[111],[111],[111],[111],[111],[111],[111],[111]

the ‘negatives’

(opposite direction)

A set of directions related by symmetry operations of the lattice or the crystal is called a

family of directions

A family of directions is represented (Miller Index notation) as: <u v w>

118](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-14-320.jpg)

![• Trace a path along the basis vectors as required by the direction. In the current example move

1unit along a1, 1unit along a2 and 2 units along a3.

• Directions are projected onto the basis vectors to determine the components and hence the Miller-

Bravais indices can be determined as in the table.

[1120]Drawing the direction

Hexagonal crystals → Miller-Bravais Indices : DIRECTIONS

Drawing the [10 0] direction1

129](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-22-320.jpg)

![ Unknown direction → [uvw]

Unknown plane → (hkl)

Double digit indices should be separated by commas → (12,22,3)

In cubic lattices/crystals [hkl] (hkl)

2 2 2

cubic lattice

hkl

a

d

h k l

Points about planes and directions

Interplanar spacing (dhkl) in cubic

lattice (& crystals)

Symbol

Alternate

symbols

Direction

[ ] [uvw] → Particular direction

< > <uvw> [[ ]] → Family of directions

Plane

( ) (hkl) → Particular plane

{ } {hkl} (( )) → Family of planes

122](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-23-320.jpg)

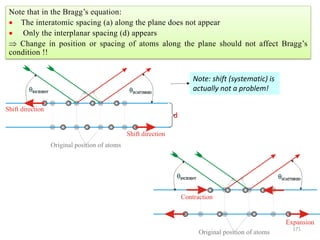

![Note: shift is actually not a problem! Why is ‘systematic’ shift not a problem?

n AY YB [180 ( )] ( )AY XY Cos XY Cos

( )YB XY Cos

[ ( ) ( )] [2 ]n AY YB XY Cos Cos XY Sin Sin

( )

d

Sin

XY

[2 ] 2

d

n Sin Sin d Sin

Sin

2n d Sin

172](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-172-320.jpg)

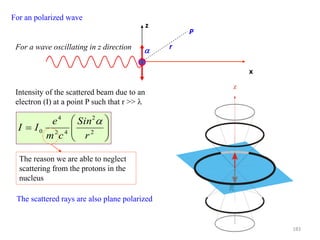

![0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

0 30 60 90 120 150 180

2t

[Cos(2t)]^2

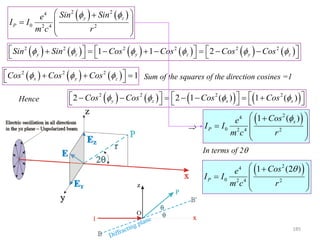

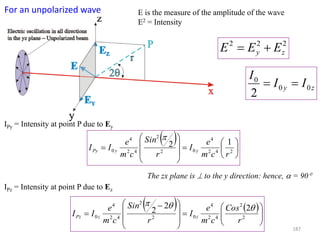

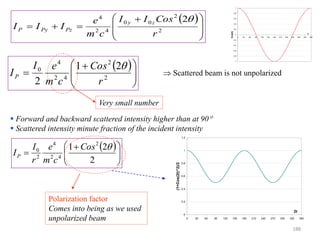

In general P could lie anywhere in 3D

space.

For the specific case of Bragg scattering:

The incident direction IO

The diffracted beam direction OP

The trace of the scattering plane BB’

Are all coplanar OP is constrained to be

on the xz plane

x

z

r

P

2

2

2

42

4

0

2

r

Cos

cm

e

II

186](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-186-320.jpg)

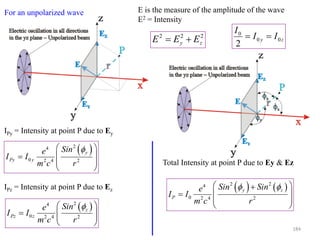

![B Scattering by an Atom

Scattering by an atom [Atomic number, (path difference suffered by scattering from

each e−, )]

Scattering by an atom [Z, (, )] Angle of scattering leads to path differences

In the forward direction all scattered waves are in phase

electronanbyscatteredwaveofAmplitude

atomanbyscatteredwaveofAmplitude

FactorScatteringAtomicf

f→

)(Sin

(Å−1) →

0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

10

20

30

Schematic

)(Sin

Coherent

scattering

Incoherent

(Compton)

scattering

Z

Sin() /

189](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-189-320.jpg)

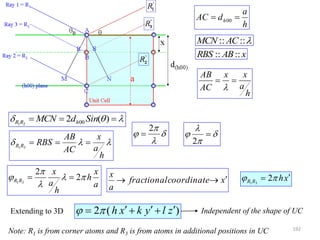

![ If atom B is different from atom A the amplitudes must be weighed by the respective

atomic scattering factors (f)

The resultant amplitude of all the waves scattered by all the atoms in the UC gives the

scattering factor for the unit cell

The unit cell scattering factor is called the Structure Factor (F)

Scattering by an unit cell = f(position of the atoms, atomic scattering factors)

electronanbyscatteredwaveofAmplitude

ucinatomsallbyscatteredwaveofAmplitude

FactorStructureF

[2 ( )]i i h x k y l z

E Ae fe

2 ( )h x k y l z

In complex notation

2

FI

[2 ( )]

1 1

j j j j

n n

i i h x k y l zhkl

n j j

j j

F f e f e

Structure factor is independent of the shape and size of the unit cell

For n atoms in the UC

If the UC distorts so do the planes in it!!

193](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-193-320.jpg)

![nni

e )1(

)(

2

Cos

ee ii

Structure factor calculations

A Atom at (0,0,0) and equivalent positions

[2 ( )]j j j ji i h x k y l z

j jF f e f e

[2 ( 0 0 0)] 0i h k l

F f e f e f

22

fF F is independent of the scattering plane (h k l)

nini

ee

Simple Cubic

1)(

inodd

e

1)(

ineven

e

194](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-194-320.jpg)

![B Atom at (0,0,0) & (½, ½, 0) and equivalent positions

[2 ( )]j j j ji i h x k y l z

j jF f e f e

1 1

[2 ( 0)]

[2 ( 0 0 0)] 2 2

[ 2 ( )]

0 ( )2

[1 ]

i h k l

i h k l

h k

i

i h k

F f e f e

f e f e f e

F is independent of the ‘l’index

C- centred Orthorhombic

Real

]1[ )( khi

efF

fF 2

0F

22

4 fF

02

F

e.g. (001), (110), (112); (021), (022), (023)

e.g. (100), (101), (102); (031), (032), (033)

195](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-195-320.jpg)

![C Atom at (0,0,0) & (½, ½, ½) and equivalent positions

[2 ( )]j j j ji i h x k y l z

j jF f e f e

1 1 1

[2 ( )]

[2 ( 0 0 0)] 2 2 2

[ 2 ( )]

0 ( )2

[1 ]

i h k l

i h k l

h k l

i

i h k l

F f e f e

f e f e f e

Body centred

Orthorhombic

Real

]1[ )( lkhi

efF

fF 2

0F

22

4 fF

02

F

e.g. (110), (200), (211); (220), (022), (310)

e.g. (100), (001), (111); (210), (032), (133)

196](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-196-320.jpg)

![D Atom at (0,0,0) & (½, ½, 0) and equivalent positions

[2 ( )]j j j ji i h x k y l z

j jF f e f e

]1[ )()()(

)]

2

(2[)]

2

(2[)]

2

(2[

)]0(2[

hlilkikhi

hl

i

lk

i

kh

i

i

eeef

eeeefF

Face Centred Cubic

Real

fF 4

0F

22

16 fF

02

F

(h, k, l) unmixed

(h, k, l) mixed

e.g. (111), (200), (220), (333), (420)

e.g. (100), (211); (210), (032), (033)

(½, ½, 0), (½, 0, ½), (0, ½, ½)

]1[ )()()( hlilkikhi

eeefF

Two odd and one even (e.g. 112); two even and one odd (e.g. 122) 197](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-197-320.jpg)

![Mixed indices CASE h k l

A o o e

B o e e

( ) ( ) ( )

CASE A : [1 ] [1 1 1 1] 0i e i o i o

e e e

( ) ( ) ( )

CASE B: [1 ] [1 1 1 1] 0i o i e i o

e e e

0F 02

F(h, k, l) mixed e.g. (100), (211); (210), (032), (033)

Mixed indices Two odd and one even (e.g. 112); two even and one odd (e.g. 122)

Unmixed indices CASE h k l

A o o o

B e e e

Unmixed indices

fF 4 22

16 fF (h, k, l) unmixed

e.g. (111), (200), (220), (333), (420)

All odd (e.g. 111); all even (e.g. 222)

( ) ( ) ( )

CASE A : [1 ] [1 1 1 1] 4i e i e i e

e e e

( ) ( ) ( )

CASE B: [1 ] [1 1 1 1] 4i e i e i e

e e e

198](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-198-320.jpg)

![E

Na+ at (0,0,0) + Face Centering Translations (½, ½, 0), (½, 0, ½), (0, ½, ½)

Cl− at (½, 0, 0) + FCT (0, ½, 0), (0, 0, ½), (½, ½, ½)

)]

2

(2[)]

2

(2[)]

2

(2[)]

2

(2[

)]

2

(2[)]

2

(2[)]

2

(2[

)]0(2[

lkh

i

l

i

k

i

h

i

Cl

hl

i

lk

i

kh

i

i

Na

eeeef

eeeefF

][

]1[

)()()()(

)()()(

lkhilikihi

Cl

hlilkikhi

Na

eeeef

eeefF

]1[

]1[

)()()()(

)()()(

khihlilkilkhi

Cl

hlilkikhi

Na

eeeef

eeefF

]1][[ )()()()( hlilkikhilkhi

ClNa

eeeeffF

NaCl:

Face Centred Cubic

199](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-199-320.jpg)

![]1][[ )()()()( hlilkikhilkhi

ClNa

eeeeffF

Zero for mixed indices

Mixed indices CASE h k l

A o o e

B o e e

]2][1[ TermTermF

0]1111[]1[2:ACASE )()()(

oioiei

eeeTerm

0]1111[]1[2:BCASE )()()(

oieioi

eeeTerm

0F 02

F(h, k, l) mixed e.g. (100), (211); (210), (032), (033)

Mixed indices

200](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-200-320.jpg)

![(h, k, l) unmixed ][4 )( lkhi

ClNa

effF

][4 ClNa

ffF If (h + k + l) is even

22

][16 ClNa

ffF

][4 ClNa

ffF If (h + k + l) is odd

22

][16 ClNa

ffF

e.g. (111), (222); (133), (244)

e.g. (222),(244)

e.g. (111), (133)

Unmixed indices CASE h k l

A o o o

B e e e

4]1111[]1[2:ACASE )()()(

eieiei

eeeTerm

4]1111[]1[2:BCASE )()()(

eieiei

eeeTerm

Unmixed indices

201](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/materialscharacterizationtechnique-160429090201/85/Materials-Characterization-Technique-Lecture-Notes-201-320.jpg)