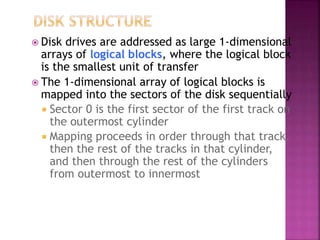

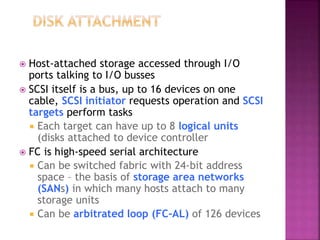

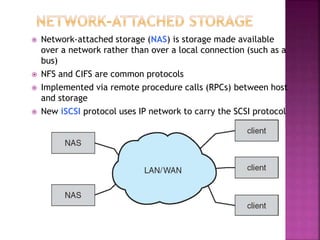

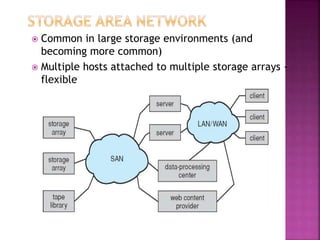

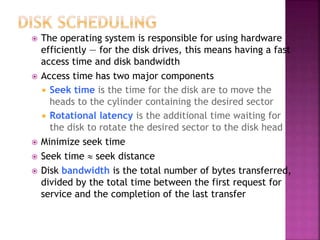

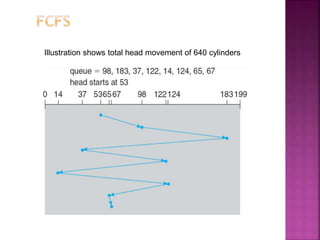

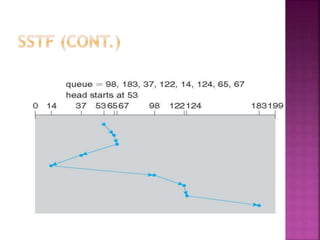

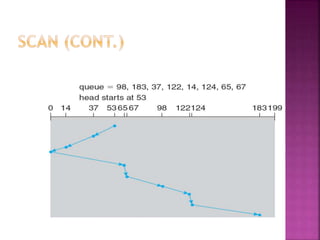

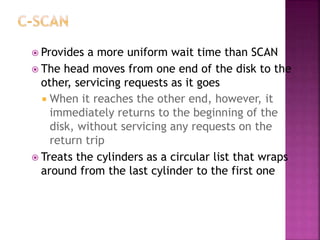

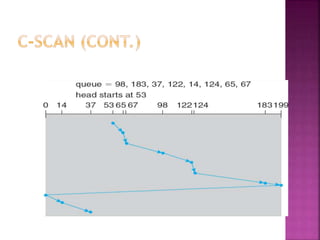

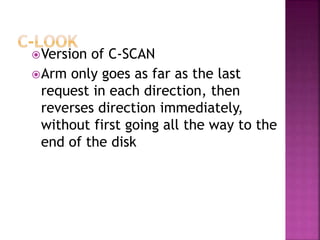

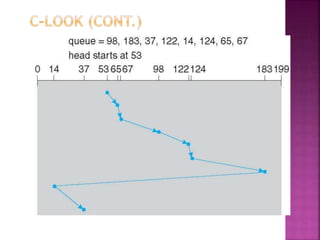

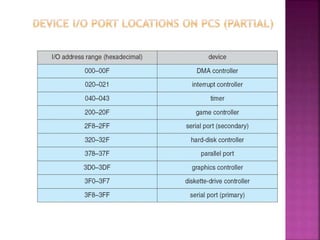

The document discusses disk drives and how they are addressed and mapped. Logical blocks on disk drives are mapped sequentially to physical sectors. Host systems access storage through I/O ports and buses like SCSI and Fibre Channel. Network-attached storage uses network protocols like NFS and CIFS. Storage area networks connect multiple hosts to multiple storage units using Fibre Channel. The operating system schedules disk I/O requests using algorithms like SSTF, SCAN, C-SCAN, and LOOK to minimize disk head movement.