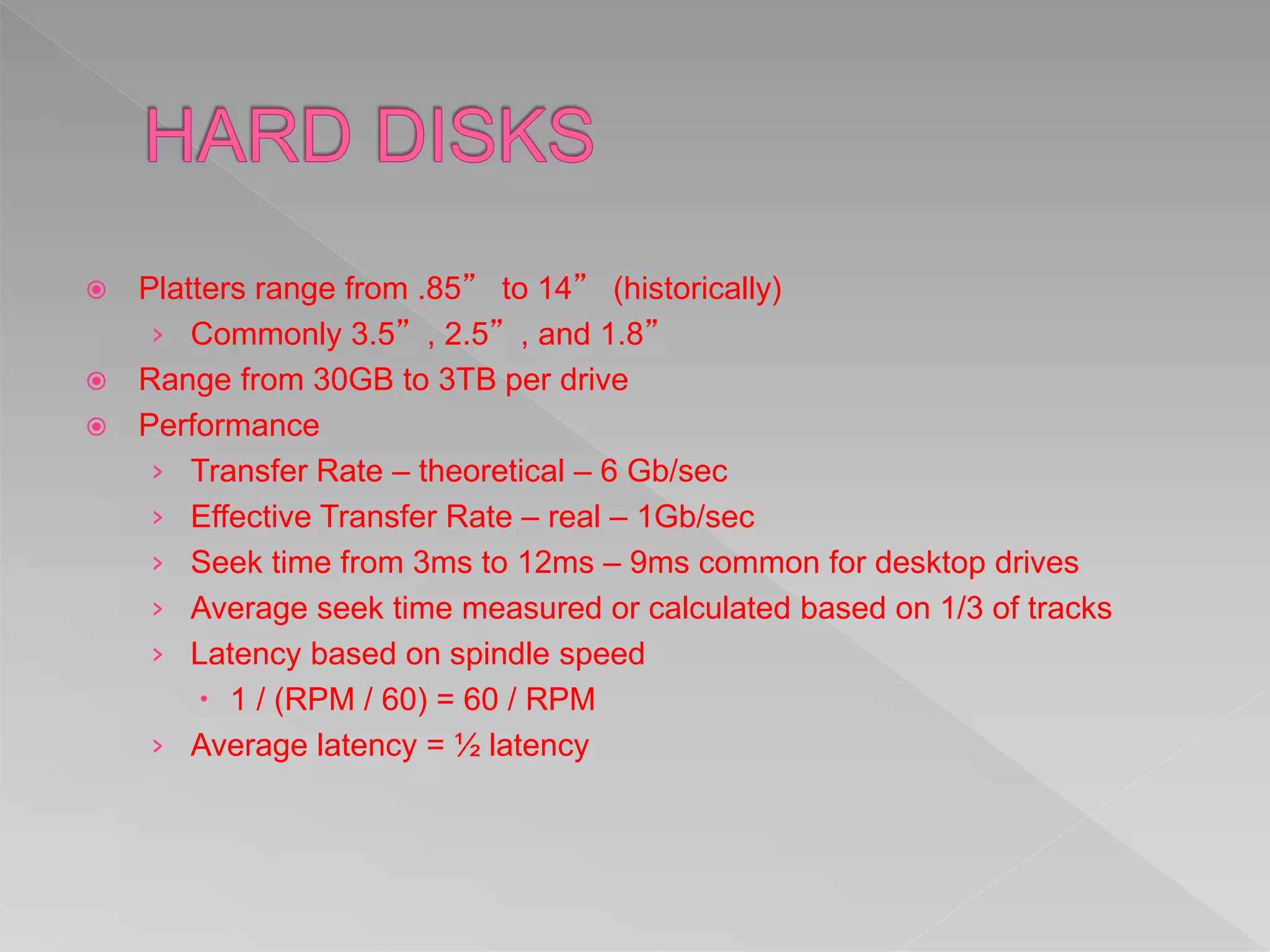

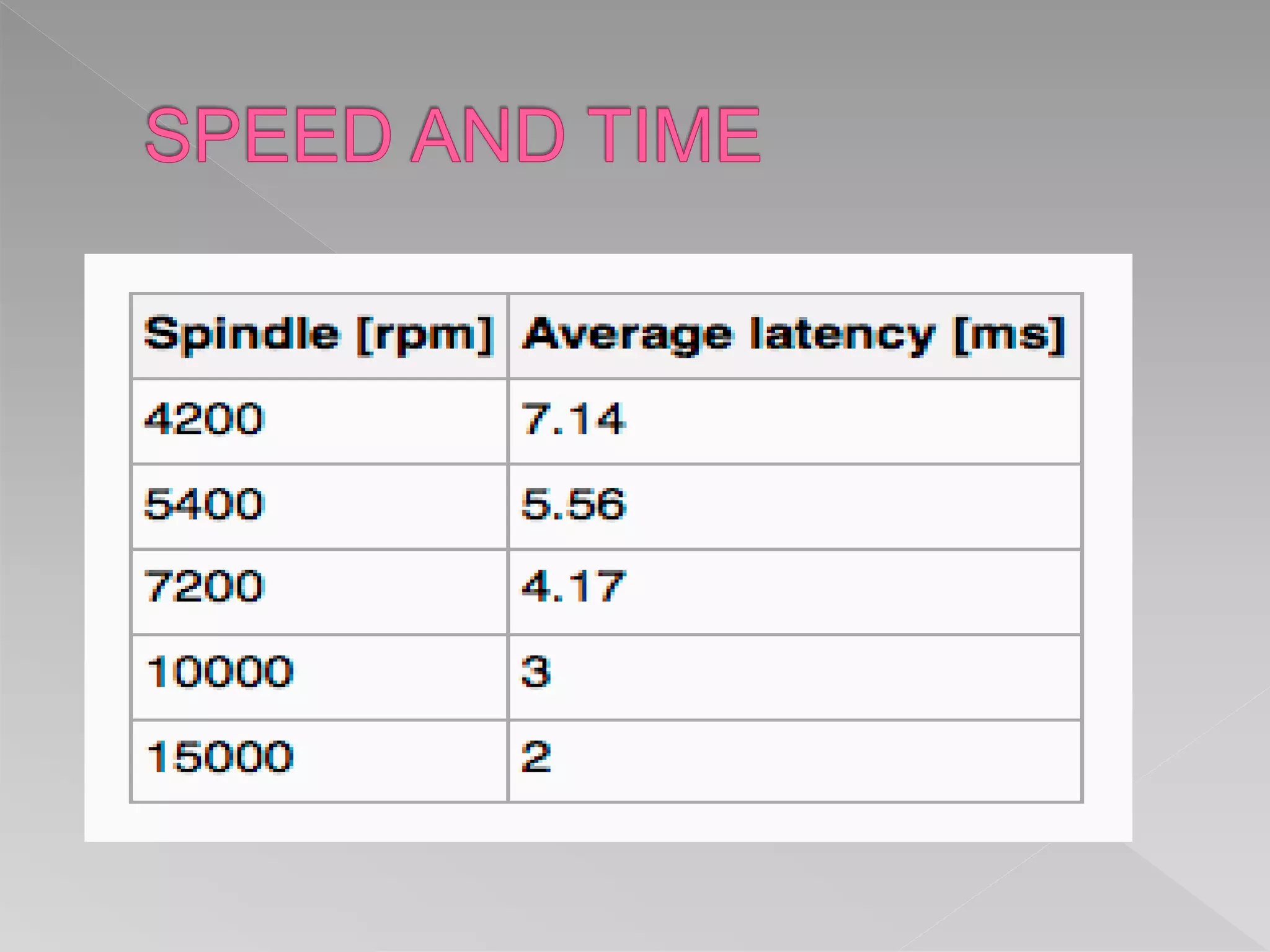

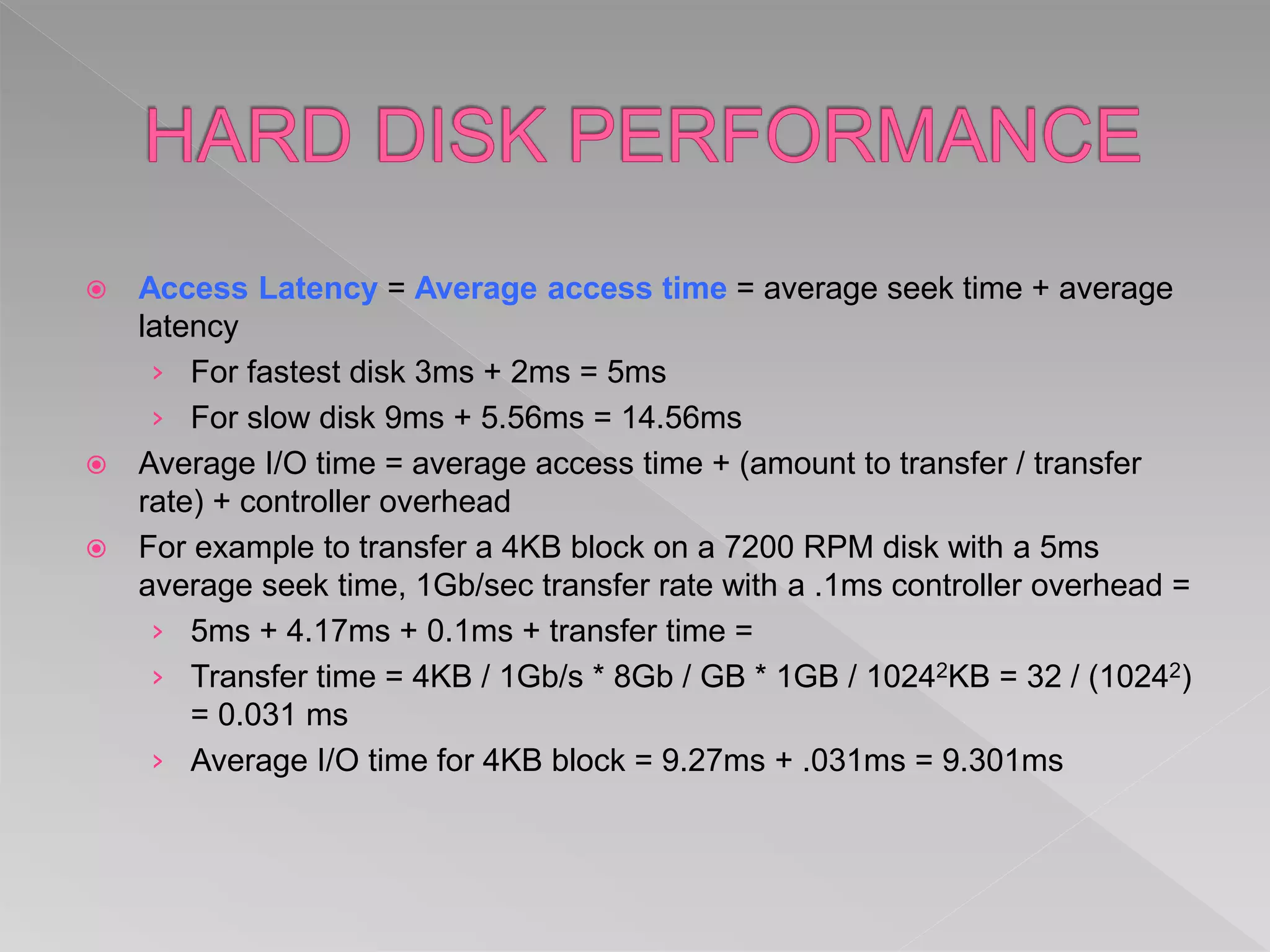

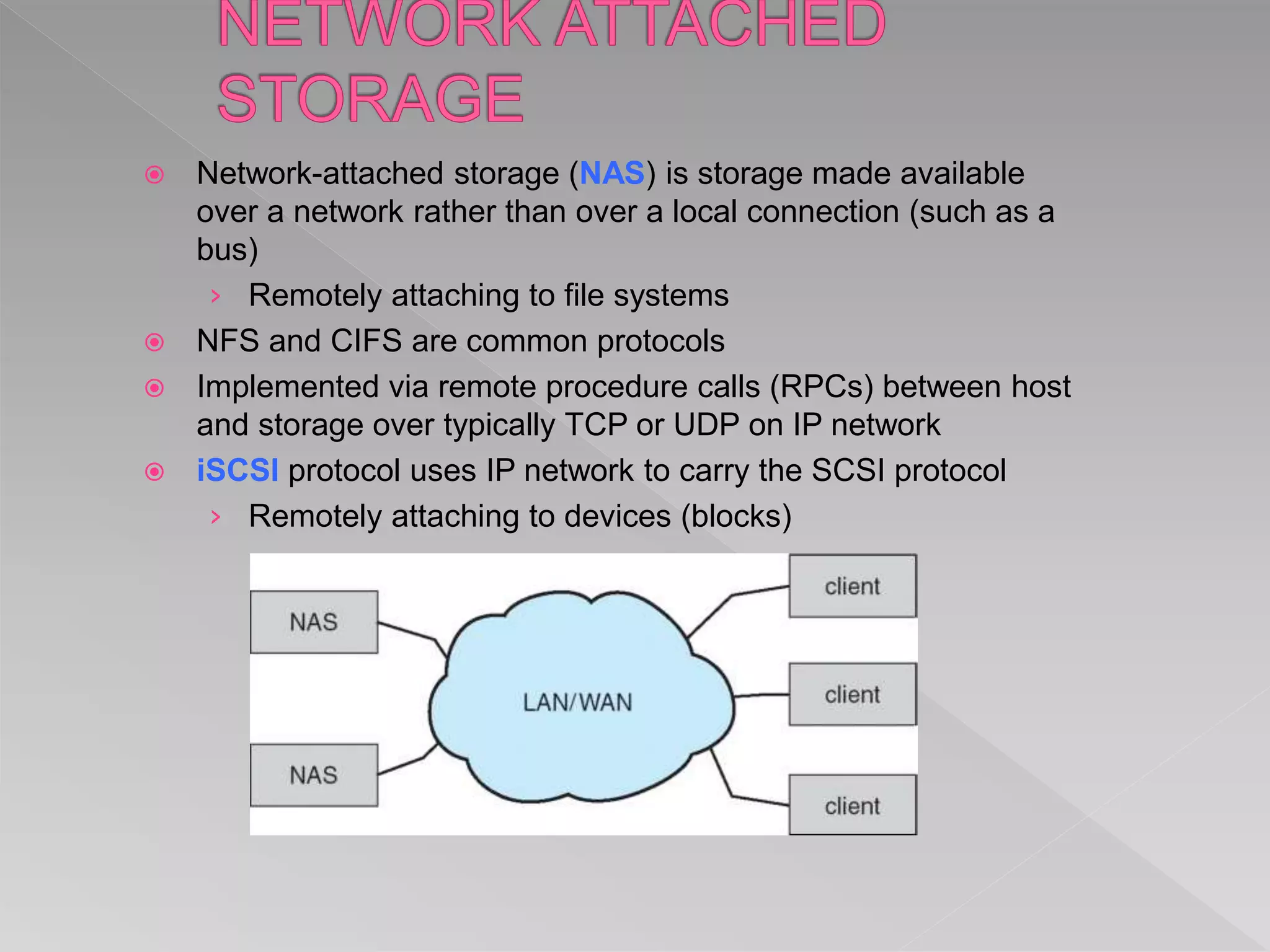

This document discusses various aspects of mass storage systems, including disk structure, disk scheduling algorithms, and operating system services for storage. It provides details on disk formatting, partitioning, and file systems. It also covers topics like swap space management, the use of raw disks versus file systems, and boot block initialization. Disk scheduling algorithms like SSTF, SCAN, C-SCAN, and LOOK are evaluated based on minimizing head movement and providing uniform wait times.