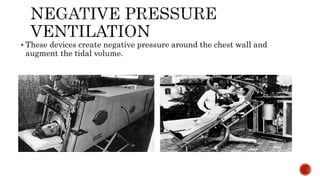

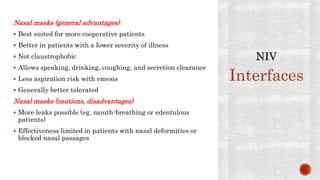

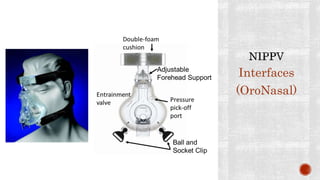

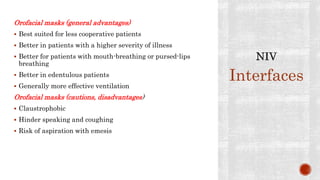

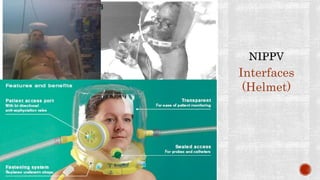

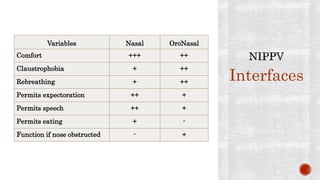

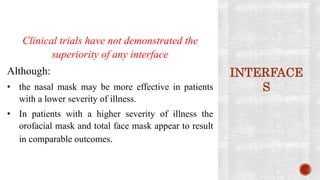

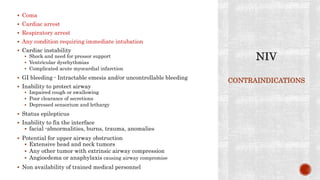

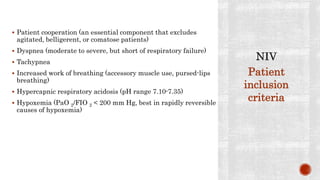

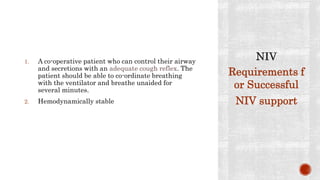

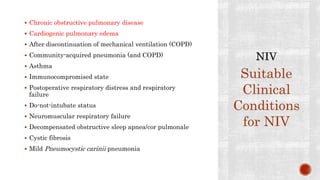

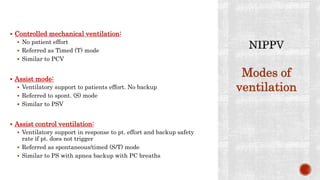

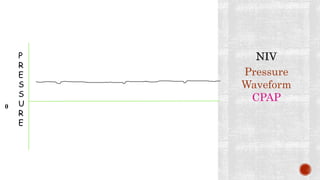

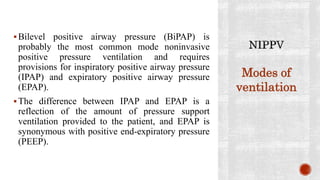

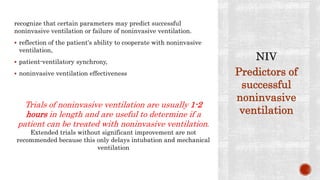

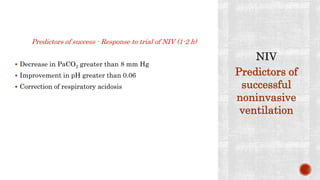

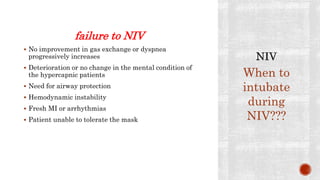

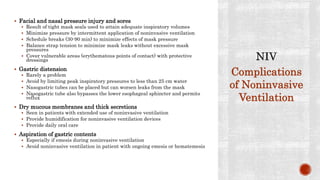

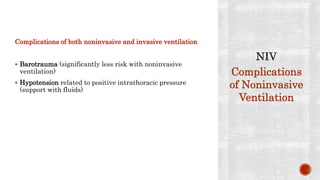

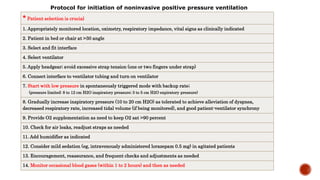

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) refers to ventilatory support without an invasive artificial airway such as an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube. NIV can be delivered via nasal or oronasal masks connected to positive pressure ventilators. The document traces the history of ventilation from ancient times to modern NIV techniques. It describes various interfaces, modes of ventilation including CPAP, contraindications, and suitable clinical conditions for NIV support such as COPD exacerbations and cardiac pulmonary edema.