1. Multilingualism refers to the use of two or more languages by an individual or community. Two examples of highly multilingual societies are South Africa and Vanuatu.

2. South Africa has 11 official languages following the end of apartheid. Vanuatu distinguishes between a national language, official languages, and languages of education which are divided between French, English, and Bislama.

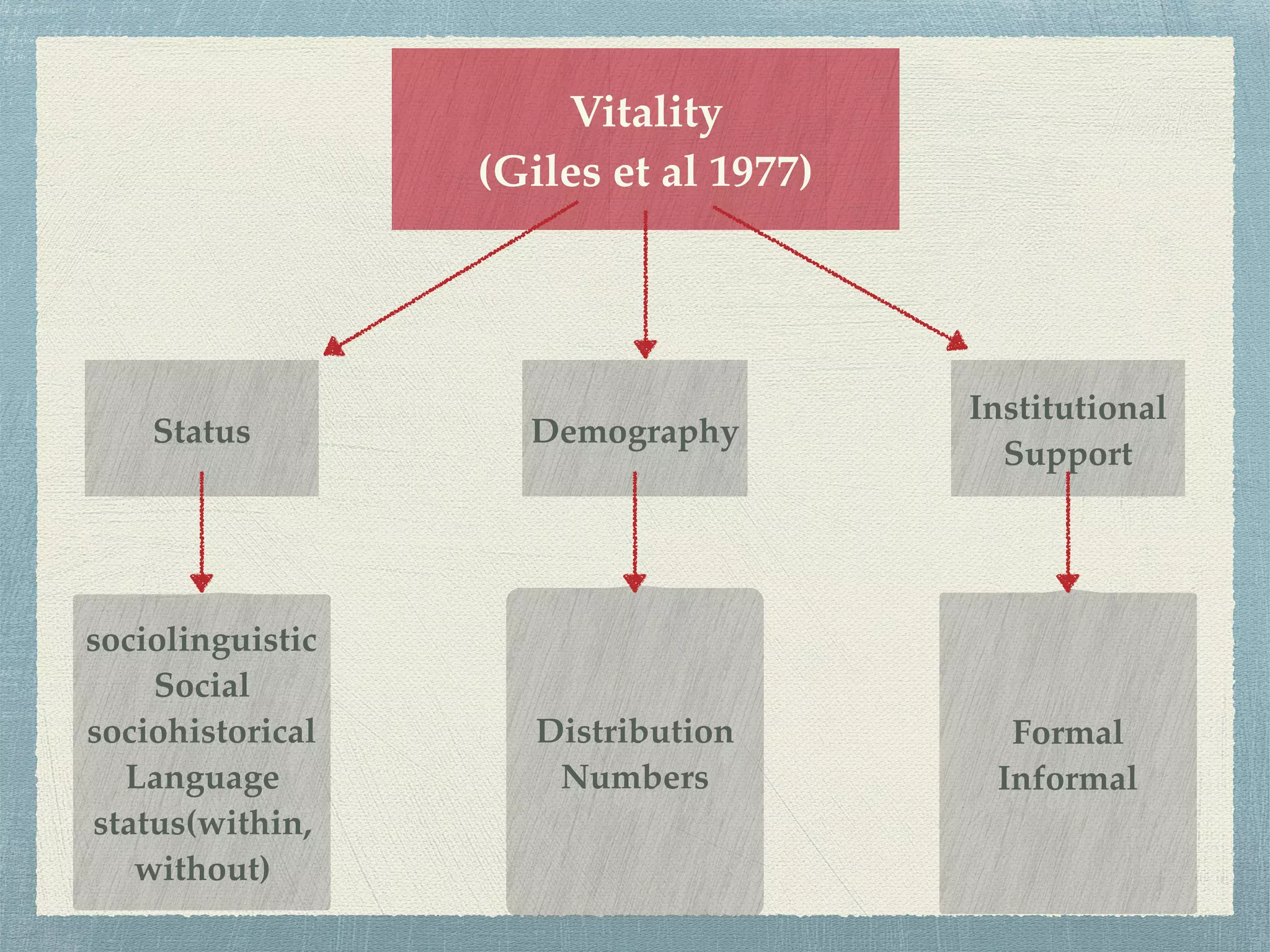

3. The vitality of a language depends on its status, institutional support, demography, and distribution. High vitality means a language is widely used over generations while low vitality means a language has been replaced.