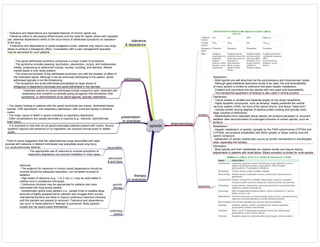

This document provides an overview of abdominal trauma, including:

1) Initial assessment involves imaging like CXR, pelvis X-ray, and neck X-ray to identify injuries. Resuscitation focuses on airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and environment.

2) Further assessment includes inspection, palpation, FAST ultrasound, and CT scan. Blunt trauma most commonly injures the spleen and liver while penetrating trauma often injures the small intestine, liver, and colon.

3) Surgical intervention is usually required for gunshot wounds while most blunt solid organ injuries can now be managed non-operatively. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage can identify bleeding but does not locate the source.

![abdominal trauma

- assessment

[created by Paul

Young 28/10/07]

initial

assessment

imaging and

laboratory

studies

definitiontrauma series:

- CXR identifies haemothorax, pneumothorax and pulmonary contusion

- AP pelvis can confirm presence of significant pelvic fracture

- lateral c-spine can identify non-survivable neck injury

resuscitation &

comprehensive

assessment

Primary survey:

(i) Airway(ability of air to pass unobstructed to the lungs):

critical findings include:

- obstruction of the airway due to direct injury, oedema, foreign body or inability

to protect the airway because of depressed level of consciousnesss

key treatment is:

- establishment of airway

(ii) Breathing (ability to ventilate and oxygenate):

key clinical findings are:

- absence of spontaneous ventilation, absent or asymmetrical breath sounds, dyspnoea

hyperresonance, dullness, gross chest wall instability or defects that compromise ventilation

key conditions to identify are:

- pneumothorax, endotracheal tube malposition, tension

pneumothorax, haemothorax, sucking chest wounds, flail chest

key treatment is:

- chest tube

(iii) Circulation:

key clinical findings are:

- collapsed or distended neck veins, signs or tamponade, external sites of haemorrhage

key conditions identified are:

- hypovolaemia, cardiac tamponade, external haemorrhage

key treatment is:

- iv access, fluid resuscitation, compression of sites of bleeding

(iv) Disability:

key clinical conditions are:

- decreased level of consciousness, pupillary assymetry, gross weakness

key conditions identified are:

- serious head and spinal cord injury

key treatment is:

- definitive airway if indicated, emergency treatment of raised icp

(v) Exposure and control of immediate environment:

- expose patient and prevent hypothermia

Resuscitation phase:

- continues throughout primary and secondary survey and until treatments are complete

- fluids are required to sustain intravascular volume, tissue and organ perfusion and urine output

- administer blood for hypovolaemia that is unresponsive to crystalloid boluses

- end points are normal vital signs, absence of blood loss, adequate urine output and no evidence of end

organ dysfunction; blood lactate and base deficit on an ABG may be helpful in patients who are severely injured

Other procedures:

several monitoring and diagnostic adjuncts occur in concert with the primary survey:

(i) ECG and ventilatory monitoring and continous pulse oximetry

(ii) decompress stomach with NG or OG tube once airway is secured

(iii) insert a foley cather during resuscitation phase (foley catheter placement is contraindicated

if urethral injury is evident as identified by blood at the meatus, ecchymosis or scrotum or

labium majora or high riding prostate - retrograde urethrogram is required for these patients)

Secondary survey of abdominal trauma:

(i) inspection:

- examine for the presence of external signs of injury noting patterns of abrasion and/or ecchymotic areas

- lap belt bruising is positively correlated with rupture of the small intestine and increased incidence of other

intraabdominal injury (20-30% of patients with lap-belt marks have associated mesenteric or intestinal injuries)

- bradycardia may indicate free intraperitoneal blood

- Cullen sign (periumbillical ecchymosis) may indicate retroperitoneal

haemorrhage; however, this usually takes hours to develop

- flank bruising and swelling may raise suspicion for retroperitoneal injury

- inspect genitals and peritoneum

(ii) palpation:

- fullness may indicate haemorrhage

- crepitation of lower rib cage may indicate hepatic or splenic injury

- rectal and vaginal examination identify potential bleeding and injury

- signs of peritonitis soon after injury suggest leakage of intestinal contents;

peritonitis due to intra-abdominal haemorrhage may take several hours to develop

FAST:

- used to identify free fluid in the peritoneal cavity

- FAST has a sensitivity of 70-95%

- involves directing to ultrasound probe in four regions:

(i) the subxipoid location to determine whether there is fluid in the pericardial

space & to make a rough assessment of contractility & filling state

(ii) the right upper quadrant

(iii) the splenorenal recess

(iv) the pelvis

- problems with FAST:

(i) operator dependent

(ii) false negative rate in children is high

(iii) technically more difficult with obesity & sc empysema

CT abdo/pelvis:

- is the diagnostic modality of choice for haemodynamically stable patients

- the major reason not to obtain a CT scan is haemodynamic instability

- allows haemoperitoneum & its source to be identified & allows specific injuries to be graded

- CT also permits evaluation of retroperitoneal structures including the kidneys, major blood vessels & bony pelvis

- the majority of blunt solid organ injuries are now managed non-operatively in trauma centres; however, a

blush of intravenous contrast agent indicates active extravasation from a bleeding vessel and is strong predictor

of failure of non-operative management

- problems with CT scanning are:

(i) the need to transfer the patient to radiology

(ii) the time associated with transfer and scanning

(iii) risks associated with intravenous contrast agents

(iv) the fact hollow viscus, diaphragmatic & pancreatic injuries are frequently missed on initial scanning

abdominal trauma consists of blunt and penetrating trauma

Penetrating abdominal trauma:

- most commonly injured organs with stab wounds are small intestine, liver and colon

- only one third of abdominal stab wounds penetrate the peritoneum & only 50% of

these require surgical intervention

- 85% of abdominal wall gun shot wounds penetrate the peritoneum & 95% of these

require a surgical procedure for correction

Blunt abdominal trauma

- spleen and liver are the most commonly injured organs; small and large intestines are the next most commonly injured

DPL:

- has an accuracy of 98% for detection of haemoperitoneum but does not determine source

- generally performed in patients too unstable for CT

- involves performing a minilaparotomy with placement of a lavage catheter into the periotoneal

cavity directed towards the pelvis

- the return of gross blood is a positive result

- if DPL is grossly negative then 1L of warmed saline is instilled into the the abdominal cavity &

then drained back into the intravenous fluid bag by gravity. The effluent lavage is sent to the

laboratory for analysis.

- laboratory criteria for a positive DPL in blunt trauma are:

(i) >100000 RBCs/mm3

(ii) >500 WBC/mm3

(iii) presence of food particles

(iv) presence of bile

(v) presence of bacteria

- problems with DPL:

(i) an invasive procedure

(ii) 1/4 of patients with a positive DPL will have a non-therapeutic laparotomy

(iii) 5% false negative rate with retroperitoneal, hollow viscus or diaphragm injuries

- ongoing haemorrhage is the most likely cause of persistent or recurrent haemodynamic instability

- initial goal is not to diagnose specific abdominal organ injury but rather to determine wheter there are

signs & symptoms that indicate a need for immediate laparotomy

30% of patients with lumbar Chance fracture have associated bowel or mesenteric injuries

criteria

for

positive

DPL](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/medicineinmindmaps-150716131716-lva1-app6892/85/Medicine-in-Mind-Maps-2-320.jpg)

![acidosis

in kidney

disease

[created

by Paul

15/12/07]

Distal

(Type 1)

Renal

Tubular

Acidosis

General

- This is also referred to as classic RTA or distal RTA.

- The problem here is an inability to maximally acidify the urine. Typically

urine pH remains > 5.5 despite severe acidaemia ([HCO3] < 15 mmol/l).

- Some patients with less severe acidosis require acid loading tests

(eg with NH4Cl) to assist in the diagnosis. If the acid load drops the

plasma [HCO3] but the urine pH remains > 5.5, this establishes the diagnosis.

General Classification of Causes of type 1 RTA

(i)Hereditary (genetic)

(ii) Autoimminue diseases (eg Sjogren's syndrome, SLE, thyroiditis)

(iii) Disorders which cause nephrocalcinosis (eg primary hyperparathyroidism, vitamin D intoxication)

(iv) Drugs or toxins (eg amphotericin B, toluene inhalation)

(v) Miscellaneous - other renal disorders (eg obstructive uropathy)

Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Reduced H+ Secretion in Distal Tubule

(i) "Weak pump"

- Inability for H+ pump to pump against a high H+ gradient

(ii) "Leaky membrane"

- Back-diffusion of H+ [eg This occurs in RTA due amphotericin B]

(iii) "Low pump capacity"

- Insufficient distal H+ pumping capacity due to tubular damage.

Investigation

- Typical findings are an inappropriately high urine pH (usually > 5.5), low acid secretion

and urinary bicarbonate excretion despite severe acidosis. Renal sodium wasting is

common and results in depletion of ECF volume and secondary hyperaldosteronism with

increased loss of K+ in the urine.

- The diagnosis of type 1 RTA is suggested by finding a hyperchloraemic acidosis in

association with an alkaline urine particularly if there is evidence of renal stone

formation.

Note: If [HCO3 > 15 mmol/l, then acid loading tests are required to establish the diagnosis.

Treatment

- Treatment with NaHCO3 corrects the Na+ deficit, restores the extracellular fluid volume

and results in correction of the hypokalaemia. Typical alkali requirements are in the range

of 1 to 4 mmol/kg/day. K+ supplements are only rarely required. Sodium and potassium

citrate solutions can be useful particularly if hypokalaemia is present. Citrate will bind

Ca++ in the urine and this assists in preventing renal stones.

Proximal

(Type 2)

Renal

Tubular

Acidosis

General

- Type 2 RTA is also called proximal RTA because the main problem is greatly impaired

reabsorption of bicarbonate in the proximal tubule.

- At normal plasma [HCO3], more than 15% of the filtered HCO3 load is excreted in the

urine. When acidosis is severe and HCO3 levels are low (eg <17 mmols/l), the urine may

become bicarbonate free.

Features

- Symptoms are precipitated by an increase in plasma [HCO3]. The defective proximal

tubule cannot reabsorb the increased filtered load and the distal delivery of bicarbonate is

greatly increased. The H+ secretion in the distal tubule is now overwhelmed by

attempting to reabsorb bicarbonate and the net acid excretion decreases. This results in

urinary loss of HCO3 resulting in systemic acidosis with inappropriately high urine pH.

The bicarbonate is replaced in the circulation by Cl-.

- The increased distal Na+ delivery results in hyperaldosteronism with consequent renal

K+ wasting. The hypokalaemia may be severe in some cases but as hypokalaemia inhibits

adrenal aldosterone secretion, this often limits the severity of the hypokalaemia.

- Hypercalciuria does not occur and this type of RTA is not associated with renal stones.

- During the NH4Cl loading test, urine pH will drop below 5.5.

- Note that the acidosis in proximal RTA is usually not as severe as in distal RTA and the

plasma [HCO3] is typically greater than 15 mmol/l.

Causes

- There are many causes but most are associated with multiple proximal tubular defects

eg affecting reabsorption of glucose, phosphate and amino acids. Some cases are hereditary.

- Causes include vitamin D deficiency, cystinosis, lead nephropathy, amyloidosis and

medullary cystic disease.

Treatment

- Treatment is directed towards the underlying disorder if possible.

- Alkali therapy (NaHCO3) and supplemental K+ is not always necessary. If alkali

therapy is required, the dose is usually large (up to 10 mmols/kg/day) because of the

increased urine bicarbonate wasting associated with normal plasma levels.

- K+ loss is much increased in treated patients and supplementation is required.

- Some patients respond to thiazide diuretics which cause slight volume contraction and

this results in increased proximal bicarbonate reabsorption so less bicarbonate is needed.

Type 3

Renal

Tubular

Acidosis

- This term is no longer used.

- Type 3 RTA is now considered a subtype of Type 1 where there is

a proximal bicarbonate leak in addition to a distal acidification defect.

Type 4

Renal

Tubular

Acidosis

General

- A number of different conditions have been associated with this type but most patients

have renal failure associated with disorders affecting the renal interstitium and tubules. In

contrast to uraemic acidosis, the GFR is greater than 20 mls/min.

- a useful differentiating point is that hyperkalaemia occurs in type 4 RTA (but

NOT in the other types).

Pathophysiology

- The underlying defect is impairment of cation-exchange in the distal tubule with

reduced secretion of both H+ and K+.

- This is a similar finding to what occurs with aldosterone deficiency and type 4 RTA can

occur with Addison's disease or following bilateral adrenalectomy.

- Acidosis is not common with aldosterone deficiency alone but requires some degree of

associated renal damage (nephron loss) esp affecting the distal tubule.

- The H+ pump in the tubules is not abnormal so patients with this disorder are able to

decrease urine pH to < 5.5 in response to the acidosis.

comparison

of RTA types

uraemic

acidosis

- The acidosis occurring in uraemic patients is due to failure of excretion of acid anions (particularly

phosphate and sulphate) because of the decreased number of nephrons. There is a major decrease

in the number of tubule cells which can produce ammonia and this contributes to uraemic acidosis.

- Serious acidosis does not occur until the GFR has decreased to about 20 mls/min. This

corresponds to a creatinine level of about 0.30-0.35 mmols/l.

- The plasma bicarbonate in renal failure with acidosis is typically between 12 & 20

mmols/l. Intracellular buffering and bone buffering are important in limiting the fall in

bicarbonate. This bone buffering will cause loss of bone mineral (osteomalacia).

- Most other forms of metabolic acidosis are of relatively short duration as the patient is either treated

with resolution of the disorder or the patient dies. Uraemic acidosis is a major exception as these patients

survive with significant acidosis for many years. This long duration is the reason why loss of bone mineral

is significant in uraemic acidosis but is not a feature of other causes of metabolic acidosis.

general

- Metabolic acidosis occurs with both acute and chronic renal failure and with

other types of renal damage. The anion gap may be normal or may be elevated.

- If the renal damage affects both glomeruli and tubules, the acidosis is a high-anion

gap acidosis. It is due to failure of adequate excretion of various acid anions due to

the greatly reduced number of functioning nephrons.

- If the renal damage predominantly affects the tubules with minimal glomerular damage,

a different type of acidosis may occur. This is called Renal Tubular Acidosis (RTA) and

this is a normal anion gap or hyperchloraemic type of acidosis. The GFR may be normal

or only minimally affected.

- Renal tubular acidosis is a form of hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis which occurs

when the renal damage primarily affects tubular function without much effect on

glomerular function. The result is a decrease in H+ excretion which is greater than can be

explained by any change in GFR. If glomerular function (ie GFR) is significantly

depressed, the retention of fixed acids results in a high anion gap acidosis.

- Three main clinical categories or 'types' of renal tubular acidosis (RTA) are now

recognised but the number of possible causes is large. The mechanism causing the defect

in ability to acidify the urine and excrete acid is different in the three types.

- Incomplete forms of RTA also occur. The arterial pH is normal in these patients and

acidosis develops only when an acid load is present.

ComparisonofMajorTypesofRTA

Type1 Type2 Type4

Hyperchloraemic

acidosis

Yes Yes Yes

MinimumUrinepH >5.5 <5.5(butusually>5.5

beforetheacidosis

becomesestablished)

<5.5

PlasmapotassiumLow-normal Low-normal high

Renal stones Yes No No

Defect ReducedH+

excretionin

distal tubule

ImpairedHCO3

reabsorptioninproximal

tubule

Impairedcation

exchangein

distal tubule](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/medicineinmindmaps-150716131716-lva1-app6892/85/Medicine-in-Mind-Maps-6-320.jpg)

![Acinetobacter

[created by

Paul Young

02/10/07]

General

- levels of environmental contamination with A. baumannii

correlate with patient colonization and infection. This organism

is very hardly and survives dessication.

- Acinetobacter are non-lactose fermenting, Gram-negative

coccobacilli that are strictly aerobic and non-motile.

- Acinetobacter baumanii is the most important species

associated with infections and nosocomial outbreaks

resistance

- Acinetobacter isolates are typically even more resistant than

Pseudomonas spp. to most antimicrobials, including broad-spectrum

cephalosporins, penicillins, fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides.

infections

- It causes a wide range of nosocomial infections including

ventilator-associated pneumonia, bacteraemia, urinary tract

infections, skin and wound infections and meningitis

colonisation

- Acinetobacters form part of the normal bacterial flora of

the skin, particularly in moist regions such as the axillae,

groin and toe webs.

- Up to 25% of normal individuals carry cutaneous Acinetobacter,

and it is the most common gram-negative organism isolated from

the skin of hospital personnel.

transmission

- Dissemination of Acinetobacter in the environment can be a major

problem.

- It has been recovered from respiratory equipment, bed linen,

tables, patients' charts, sink traps, the floor and atmosphere,

especially in the vicinity of an infected or colonized patient

- Furthermore, Acinetobacter is able to persist in the environment

for several days, even in dry conditions, on particles and dust.

- Some strains are tolerant to soaps and disinfectants.

- The nosocomial spread of Acinetobacter is most often attributed

to exogenous contamination from equipment, environmental

surfaces and the hands of hospital personnel rather than endogenous

infection.

- Known resistance mechanisms include plasmid-mediated beta-lactamases,

which are also frequently associated with resistance to fluoroquinolones

and aminoglycosides.

- Chromosomal cephalosporinases may be responsible for the high

prevalence of ceftazidime resistance. However, the relationship

between observed antibiotic resistance patterns in vitro and the presence

of these beta-lactamases remains unclear. It is suggested that altered

penicillin-binding proteins and membrane impermeability may be the

major cause of high level resistance to beta-lactams, including imipenem

treatment

- Carbapenems are currently considered the antimicrobials of choice, although

epidemic outbreaks and endemic situations involving carbapenem-resistant

Acinetobacter species have been described

- Colistin, polymyxin B & ampicillin-sulbactam have all been

described in treatment of carbapenem-resistant strains](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/medicineinmindmaps-150716131716-lva1-app6892/85/Medicine-in-Mind-Maps-7-320.jpg)

![acute

coronary

syndromes

[created by

Paul Young

06/10/07]

general - coronary artery disease accounts for over 30% of deaths in Western countries.

classification

Unstable angina:

- ischaemic chest pain with is recent in origin, is more frequent, severe, or

prolonged than the patient's usual angina; is more difficult to control with drugs;

or is occurring at rest or with minimal exertion

- cardiac biomarkers are not elevated

Myocardial infarction:

- ischaemic symptoms with raised cardiac biomarkers

- STEMI: ST elevation

- NSTEMI: no ST elevation

risk

factors

modifiable:

(i) by life-style

- smoking

- obesity

- physical inactivity

(ii) by pharmacotherapy or lifestyle

- hypertension

- dyslipidaemia

- diabetes

- hyperhomocysteinaemia

non-modifiable:

- increasing age

- male gender

- family history

ECG

changes

in AMI

hyperacute (0-20 minutes)

- tall peaking T waves & progressive upward curving & elevation of ST segments

acute (minutes - hours)

- persistent ST elevation with gradual loss of R wave in the infarcted area.

ST segments begin to fall & there is progressive inversion of T waves

early (hours to days)

- loss of R wave and development of pathological Q waves in the area of ischaemia.

Return of ST segments to baseline with persistence of T wave inversion

indeterminate (days to weeks)

- pathological Q waves with persisting T wave inversion.

ST segments normalise (unless there is aneurysm)

old (weeks to months)

- persisting deep Q waves with normalised ST segments

anatomical

patterns of

myocardial

injury

biomarkers

in ACS

Troponin I or T:

- troponin rise indicates myonecrosis & is a high risk feature in non ST elevation acute coronary syndrome

- troponin remains elevated for 5-14 days and therefore may not be useful for identifying early reinfarction

-troponin elevation is often delayed by 4-6 hours after infarction

CK:

- should be monitored for 48 hours serially & can be measured subsequently if there is suspected reinfarction

CK-MB:

- more specific than CK for myocardial infarction & may be used to confirm a reinfarction

management

of ST

elevation AMI

reperfusion therapy:

- reperfusion can be obtained with fibrinolytic therapy or PCI

- a combination of fibrinolysis and PCI can also be used

- CABG surgery may occasionally be more appropriate with particular anatomy

& may be considered as rescue therapy in patients who fail revascularisation

- PCI is the best available treatment; however, benefit depends on prompt access to service and

if delay is longer than 90 minutes until balloon inflation thrombolysis should be administered.

- PCI is clearly better in the presence of cardiogenic shock

antiplatelet therapy:

- aspirin 300mg should be given to all patients with STEMI unless contraindicated

- both the VA Cooperative Study Group and the Canadian Multicentre Trial showed that aspirin reduces the

risk of death or myocardial infarction by 50% in patients with unstable angina or non-Q wave infarction

- clopidogrel should be given as a load 600mg to all patients who require a stent

& should be continued for at least 12 months; clopidogrel should be given to selected

patients given fibrinolysis. If urgent CABG is likely, clopidogrel should be withheld

- in the CURE trial, clopidogrel given in addition to aspirin within 24hrs of unstable angina symptoms led to significantly

reduced of cardiovascular death from 11.4% to 9.3% but was associated with a 1% absolute increase in major, non

life threatening bleeds as well as a 2.8% increase in major bleeds associated with CABG within 5 days

- ticlopidine & clopidogrel (thienopyridins) are second generation platelet inhibitors acting independently

& theoretically synergistically with aspirin

antithrombin therapy:

(i) with PCI: unfractionated heparin should be administered with dose dependent or whether IIb/IIIa

inhibitors are used; the role of enoxaparin in acute STEMI following PCI remains to be determined

(ii) with fibrinolysis: heparin or enoxaparin should be used fibrin-specific fibrinolytic

agents. The use of antithrombin therapy in conjuction with streptokinase is optional.

glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors:

- reasonable to use post primary PCI although data are conflicting regarding efficacy. They reduce mortality

the 30-day risk of non-fatal AMI by 38& in NSTEMI in patients undergoing PCI. They have not been shown to

be beneficial in the routine management of medically treated patients (GUSTO-IV-ACS)

- there are two classes of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

(i) murine monoclonal (eg abciximab)

(ii) 'small molecule' inhibitors (eg tirofiban & eptibatide)

- should be avoided with fibrinolytic therapy because of risk of bleeding; platelet infusion may treat significant

bleeding in patients receiving abciximab but not in those receiving tirofiban or eptifibatide)

risk stratification of

non ST elevation

acute coronary

syndromes

(i) high risk consists of clinical features of ACS with any of the following:

- repetitive or prolonged (>10mins) ongoing CP

- elevated cardiac biomarkers

- persistent or dynamic ECG changes (ST depression or TWI)

- transient ST elevation

- cardiogenic shock

- sustained VT

- syncope

- EF<40%

- prior CABG

- percutaneous coronary intervention within 6 months

- presence of known diabetes with typical ACS features

- chronic renal failure with typical ACS features

(ii) intermediate risk consists of clinical features with any of the following:

- resolved chest pain that occurred at rest or was repetitive or prolonged

- age >65

- known CAD

- two or more of the following risk factors (hypertension, family history, active smoking or hyperlipidaemia)

- presence of known diabetes mellitus with atypical ACS features

- presence of chronic renal failure with atypical ACS features

- prior aspirin use

(iii) low risk

- presentation with clinical features of an acute coronary syndrome without intermediate or high risk features

management of

non ST elevation

acute coronary

syndromes

- high risk patients require aggressive medical management and coronary angiography

- intermediate risk patients require inpatient monitoring and investigation and provocative testing

- low risk patients can be discharged with follow-up

- earliest rise of CK & CK-MB occurs at 3-4 hours with a peak at 12-24 hours and normalisation by 48 hours

criteria for AMI in LBBB

(i) new LBBB

(ii) concordant ST elevation of >1mm

(iii) concordant ST depression of >1mm in V1, V2 or V3

(iv) discordant ST elevation of >5mm

nitrates:

- reduce myocardial oxygen demand through afterload reduction and may on improve myocardial

oxygen delivery through coronary vasodilation

- may lead to dramatic resolution of ischaemia in coronary vasospasm

- GISSI-3 and ISIS-4 trials failed to demonstrate mortality reduction from acute or chronic nitrates; nevertheless,

they remain first line therapies for symptomatic angina and when myocardial infarction is complicated by CCF

beta blockers:

- iv beta blockers should be considered for patients with tachycardia or hypertension post infarct in the acute setting

- oral beta blockers decrease mortality after myocardial infarction and should be administered to all patients who can tolerate them

ACEIs:

- SAVE trial showed that captopril in patients with EF<20% post AMI lead to a 21% reduction in mortality

- ISIS-4 showed a smaller reduction in mortality for all patients treated with captopril post AMI

- HOPE showed patients with vascular disease or high risk of atherosclerosis benefited from ramipril

statins:

- decrease risk of adverse ischaemic events in patients with CAD thrombolysis

contraindications

absolute contraindications:

(i) active bleeding or bleeding diasthesis (excluding menses)

(ii) significant closed head injury or facial trauma within 3 months

(iii) suspected aortic dissection

(iv) risk of intracranial haemorrhage (any prior ICH, ischaemic

stroke within 3 months, cerebral vascular lesion, brain tumour)

relative contraindications:

- risk of bleeding

(i) current use of anticoagulants (the higher the INR the higher the risk)

(ii) non-compressible vascular punctures

(iii) recent major surgery

(iv) prolonged CPR >10 minutes

(v) internal bleeding within 4 weeks

(vi) active peptic ulcer

- risk of ICH

(i) history of chronic, severe, poorly controlled hypertension

(ii) severe uncontrolled HTN on presentation (>180mmHg systolic; or >110mmHg diastolic)

(iii) ischaemic stroke more than 3 months previously

- other

(i) pregnancy

- ESSENCE trial showed that low molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin) reduced the combined

end point of death, MI or recurrent ischaemia at both 14 & 30 days when compared with heparin

heart

block

in AMI

- 8% of patients with MI will only display ST elevation in posterior or right precordial leads](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/medicineinmindmaps-150716131716-lva1-app6892/85/Medicine-in-Mind-Maps-8-320.jpg)

![Acute

Pancreatitis

[created by

Paul Young

02/10/07]

classification

& definitions

- The widely used Atlanta classification categorizes acute

pancreatitis as mild or severe.

- pancreatitis is classified as severe any of the following 4 criteria are met:

(1) Organ failure with 1 or more of the following:

-shock systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg),

- pulmonary insufficiency (PaO2 <60 mm Hg),

renal failure (serum creatinine level >176.8 ìmol/L after rehydration, and

gastrointestinal tract bleeding (>500mL in 24 hours);

(2) local complications such as:

- necrosis,

- pseudocyst,

- or abscess;

(3) at least 3 of Ranson’s criteria

(4) at least 8 of the APACHE II criteria.

Pancreatic necrosis:

- Pancreatic necrosis is the presence of a diffuse or focal area of nonviable

pancreatic parenchyma, often associated with peripancreatic necrosis.

- Severe acute pancreatitis with pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis is also

referred to as necrotizing pancreatitis.

Infected pancreatitis:

- Initially a sterile necrosis (mortality, 10%), necrotizing pancreatitis becomes

infected with bacteria of gut origin in 40% to 70% of cases2 and is then called

infected necrosis (mortality, 25%).

Pancreatic pseudocyst:

- Pancreatic pseudocyst is a collection of pancreatic juice enclosed by

a wall of fibrous or granulation tissue that develops as a result of a persistent

leak of pancreatic juice from the pancreatic duct.

Pancreatic abscess:

- Pancreatic abscess is a circumscribed intra-abdominal collection of pus

that sometimes contains gas.

- It follows infection of a limited area of pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis

and usually takes 4 to 6 weeks to evolve.

Aetiology

- From several large studies describing patients with severe

acute pancreatitis, the 2 most common causes of SAP are:

(i) chronic heavy alcohol use (approximately 40% of patients) and

(ii) gallstones (approximately 35% of patients).

- Less common causes of severe acute pancreatitis are:

(i) trauma to the pancreas,

(ii) hypercalcemia,

(iii) hypertriglyceridemia,

(iv) complications from ERCP or surgery.

(v) cystic fibrosis

(vi) infectious causes including HIV, EBV, CMV & viral

hepatitis as well as mycoplasma & campylobacter

(vii) drugs, poisons & toxins including organophosphates

- azathiprine, thiazides, mercaptopurine, valproate,

didanosine, pentamidine, cotrimoxazole & scorpion

envenomation

- In about 20% of patients, no cause can be identified.

Epidemiology

- Severe acute pancreatitis occurs in men more often than in women.

- Alcoholic pancreatitis is more common among men;

gallstone pancreatitis is more common among women.

Diagnosis

- Patients with SAP typically complain of fairly sudden onset of severe upper

abdominal pain, radiating to the back, often associated with nausea and vomiting.

- Marked elevations in serum amylase and/or lipase (>3 times the upper limit

of normal) support the diagnosis of pancreatitis in a patient with severe abdominal

pain. However, modest elevations of pancreatic enzymes may be observed in other

intra-abdominal emergencies.

- In the presence of pancreatitis, an increase in liver enzyme values, especially

of alanine aminotransferase to more than 3 times normal, suggests a biliary cause.

Imaging

Ultrasound

Abdominal ultrasonography can be used to detect gallstones,

although bowel gas may limit its accuracy in the acute setting.

CT

Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) is useful for differentiating SAP from

other conditions presenting with abdominal pain and elevated pancreatic enzymes.

It also helps to delineate local complications associated with SAP:

- Pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis is diagnosed when some or all

of the pancreas or surrounding area fails to enhance with contrast.

- To determine whether a necrotic area is infected, it can be sampled by fine-needle

aspiration under CT guidance and analyzed with Gram stain and culture for evidence

of gut-derived bacteria and/or fungal organisms.

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging is better than CT for distinguishing between

an uncomplicated pseudocyst and one that contains necrotic debris

MRCP and ERCP

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasonography

can detect small bile duct stones as a cause of SAP.

Treatment

General:

- The initial treatment of SAP is supportive. Aggressive fluid resuscitation,

oxygen supplementation, and pain relief are critical.

- Interventions used in the past aimed at resting the pancreas (nasogastric suction and

acid suppression), diminishing secretion of enzymes (glucagon and somatostatin

administration), and countering the damaging effects of enzymes (use of

aprotinin, gabexate, or lexipafant) do not improve outcomes

Nutrition:

- In the past, patients with severe acute pancreatitis were administered parenteral nutrition

in an effort to avoid stimulation of the pancreas. More recently, it has been shown in animal

models that enteral nutrition prevents intestinal atrophy and improves the barrier function of

the gut mucosa.

- Three RCTs have demonstrated that enteral feeding is not only safe and feasible but

is also associated with fewer infectious complications, and is less expensive than TPN.

- Enteral feeding should be commenced whereever possible

Prevention of Pancreatic Infection:

- Pancreatic or peripancreatic infection develops in 40% to 70% of patients

with pancreatic necrosis and is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality

- Infection usually occurs at least 10 days after the onset of SAP.

- Methods to reduce the incidence of infection in patients with SAP include:

(i) selective gut decontamination - unproven

(ii) prophylactic systemic antibiotics - use of broad spectrum antibiotics is

supported by metanalysis data but may lead to fungal superinfection

- If fever or leukocytosis persists or develops beyond 7 to 10 days without an obvious

source of infection, fine-needle aspiration of the necrotic area should be performed

to rule out infection.

ERCP:

- A metaanalysis of 4 RCTs of endoscopic sphincterotomy

in patients with severe biliary pancreatitis showed that sphincterotomy

reduced complications and mortality of SAP in patients with biliary obstruction

or cholangitis.

- The role of early ERCP in patients without biliary obstruction or cholangitis is unclear.

One study reported higher mortality after ERCP in such patients.

- An accepted practice is to perform endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with

evidence of biliary obstruction (cholangitis, jaundice) or elevated liver test results

except in those with rapidly normalizing test results.

Surgery:

- Debridement by surgery or a less invasive technique is indicated in

patients with infected necrosis. Outcomes are better if surgery is delayed

until the necrosis has organized, usually about 4 weeks after disease onset.

- The preferred surgical procedure for SAP is necrosectomy (debridement) with

the placement of wide-bore drains for continuous postoperative irrigation.

- For patients who are poor surgical candidates or who have well-contained infection,

minimal-access necrosectomy by either percutaneous or endoscopic routes

has shown encouraging results.

- For patients with biliary pancreatitis, cholecystectomy should be performed during

the initial hospitalization or after the resolution of intraabdominal inflammation to

prevent recurrence. In patients too ill to undergo cholecystectomy, endoscopic

sphincterotomy is an alternative.

CT grading

Prognosis

- mild acute pancreatitis has a mortality rate of less than 1%

- the death rate for severe acute pancreatitis is 10% with sterile

and 25% with infected pancreatic necrosis.

- Approximately half the deaths of patients with SAP occur within 2 weeks of

onset. Early morbidity and mortality in patients with SAP are attributable to

organ failure secondary to systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

- The remaining deaths occur because of later complications of infected necrosis.

indications for CT

indications for surgery

Ranson's criteria](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/medicineinmindmaps-150716131716-lva1-app6892/85/Medicine-in-Mind-Maps-9-320.jpg)

![acute renal

failure

[created by

Paul Young

30/12/07]

definition

- Numerous papers highlight the lack of a universal definition for ARF in ICU. One

review of the subject found 26 different definitions of postoperative ARF in 26 studies

- Even a consensus conference of intensivists and nephrologists on the subject in 2000

could not provide an adequate, universal definition. This makes it difficult to draw

conclusions from all the individual trials that are published.

epidemiology

- Acute renal failure (ARF) is a common problem in intensive care. It is said to have an

incidence of 10-25%. The diagnosis of ARF is not difficult, although the term ARF

encompasses a broad range of definitions with no universally accepted definition

- A specific definition of disease with tight exclusion criteria is essential in the design of

clinical studies of a heterogeneous syndrome

Particular issues around definition include

(i) Biochemistry:

- Is the absolute increase or the rate of increase of serum creatinine and urea important for

the definition? Are acid-base imbalance, serum potassium level and urine output

significant in the diagnosis?

(ii) Chronic renal impairment:

- How is this incorporated into the definition and what impact does it have on diagnosis,

management and outcome?

(iii) Resuscitation:

- Should reversible elements be corrected before the definition is applied? For example, is

the correction of mean arterial pressure and filling pressures to normal physiological

values necessary before ARF can be diagnosed?

(iv) Nephrotoxic drugs:

- what are the implications of nephrotoxic drugs, e.g. gentamicin or non-steroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs, for the definition and the aetiology?

(v) Pathophysiology:

- The underlying pathophysiological process is thought to be important to outcome.

Should this be included if it is known or should it be categorized according to aetiology?

(vi) Post-renal ARF:

- Causes of postrenal ARF often have a very different natural history and outcome; if this

is identified, should they be excluded?

(vii) Confounding factors:

- does an upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage or rhabdomyolysis need to be ruled out?

- The combined published results for ARF, its incidence and outcome are:

o An incidence of 10-25%.

o Patients who are admitted with or develop ARF on the ITU have an overall mortality of 23-80%

o Patients with ARF not requiring RRT have a mortality of 10-53%

o Patients who develop ARF that requires RRT have a higher mortality of 57-80%

o Of those patients with ARF who receive RRT and survive, only 5-30% require longer-term dialysis.

o The mortality of patients who are admitted to ITU with ARF, or who go on to develop ARF, remains high.

- This wide variation in published results (up to six-fold) is due in part to the following

problems that are not specifically addressed in the majority of studies:

(i) Inclusion criteria vary between studies because the definition of what constitutes ARF is so variable.

(ii) There is significant heterogeneity of the population in terms of severity of illness and demographics.

(iii) Many different disease processes can cause ARF, so one may not be comparing like with like.

Is it the incidence of ARF that varies or the incidence of the disease process in different centres?

(iv) Different disease processes have different incidences of renal damage and mortality.

(v) Some centres are moving to the early initiation of RRT, often prior to the

development of 'criteria' to define ARF. Should this group be considered separately?

(vi) Outcome analysis varies: 14-day, 15-day, 28-day and 30-day mortality have all been used

as endpoints. Alternatively, ICU, in-hospital or 1-year mortality figures have been used.

parenchymal

renal failure

general:

- this is used to define a syndrome where the principle source of damage is within

the kidney and where typical structural changes can be seen on microscopy

- pathogenesis of parenchymal renal failure is generally immunological and varies

from vasculitis to interstitial nephropathy

aetiology

- more than 1/3rd of patients who develop ARF in ICUs have chronic renal dysfunction

due to factors such as age related changes, long-standing changes, long-standing

hypertension, diabetes or renal vascular disease

drug-induced renal failure

- many cases of drug-induced renal failure improve rapidly on removal of the offending

agent and accordingly a drug history is important in all cases of renal failure

hepatorenal failure

(i) general:

- a form of ARF that occurs in the setting of severe liver dysfunction in the absence of other

known causes of ARF. Typically, it presents as progressive oliguria with a very low urinary

sodium (<10mmol/L)

- pathogenesis is not well understood but it is thought to involve severe vasoconstriction

(ii) differential diagnosis:

- other causes of acute renal failure are more common than hepatorenal syndrome in severe

liver disease. They include sepsis, paracentesis-induced hypovolaemia, alcoholic cardiomyopathy

or any combination of these

(iii) prevention and treatment:

- the use of albumin in patients with SBP has been shown to reduce renal failure in an RCT

- studies suggest vasopressin derivatives (terlipressin) may improve GFR

rhabdomyolysis-associated ARF

- accounts for 5-10% of cases of ARF in ICU depending on the setting

- pathogenesis involves pre-renal, renal and post renal factors

- typically seen following major trauma, drug overdose & vascular embolism

- treatment principles are based on retrospective data and include aggressive fluid resuscitation,

elimination of causative agents, correction of compartment syndromes, alkalinisation of urine

(pH>6.5), and maintenance of polyuria

prognosis

- Renal replacement therapy (RRT) is now a routine element of organ support in the

intensive therapy unit (ITU). Yet despite great improvements in the recognition

and management of ARF, including RRT, the mortality of patients who are admitted to

ITU with ARF, or who subsequently develop ARF, remains high at 23-80%.

- if the cause of ARF has been removed and he patient has become physiologically stable slow recovery

occurs over 4-5 days to 3-4 weeks; in some cases the urine output can be above normal for several days

prevention

general:

- the fundamental principle of acute renal failure is to treat its cause.

- if pre-renal factors contribute these must be identified and haemodynamic

resuscitation quickly instituted

resuscitation:

- intravascular volume must be maintained or rapidly restored & oxygenation must

be maintained; an adequate haemoglobin concentration should be maintained

- once intravascular volume has been restored, some patients remain hypotensive.

In these patients autoregulation of renal blood flow may be lost & increasing MAP

with vasopressors may increase GFR; the role of additonal fluid in a patient with

normal blood pressure and cardiac output is questionable

- despite the above measures pre-renal renal failure may develop if cardiac output

is inadequate

nephroprotective drugs:

(i) 'low dose' dopamine

- evidence of efficacy or safety is lacking; however, this agent is a tubular diuretic

and occasionally increases urine output

- randomised controlled trial evidence in critically ill patients shows that low-dose

dopamine is no more effective than placebo in prevention of renal dysfunction; however,

in patients with low cardiac output dopamine may increase cardiac output, renal blood

flow and GFR (as would dobutamine or milrinone)

(ii) mannitol

- animal experiments offer some encouraging findings; however, no human data exist to

support its clinical use

(iii) loop diuretics

- these agents may protect the loop of Henle from ischaemic from decreasing its transport

related workload; however, there are no double blind randomised controlled trials proving

that these agents reduce the incidence of renal failure

- several studies support the view that loop diuretics may decrease the need for dialysis

in patients developing acute renal failure. They appear to achieve this by inducing polyuria

which results in the prevention or easier contorl of volume overload, acidosis & hyperkalaemia

- because avoiding dialysis simplifies treatment and reduces the cost of care, loop diuretics

may be useful

(iv) other agents

- other experimental agents include theophylline, urodilatin and anaritide (a synthetic atrial

natriuretic factor)

investigation

general investigations include:

(i) examination of urinary sediment and exclusion of a urinary tract infection (most if not all patients)

(ii) careful exclusion of nephrotoxins (all patients)

(iii) exclusion of obstruction (some patients)

special investigations may include:

(i) CK and myoglobin (for rhabdomyolysis)

(ii) chest x-ray, blood film

(iii) specific antibodies (anti-GBM, antidsDNA, anti-smooth muscle etc)

(iv) LDH, haptoglobin, unconjugated bilirubin

(v) cryoglobulins

(vi) Bence Jones Proteins

(vii) renal biopsy

- differentiation of prerenal and renal failure has limited clinical implication

because they are part of the same continuum and treatment is the same

post-renal

failure

general:

- obstruction to urine outflow is the most common cause of functional

renal impairment in the community but is uncommon in the ICU

- involves humoral and mechanical factors

aetiology:

- typical causes include bladder neck obstruction from an enlarged prostate, ureteric obstruction

from pelvic tumours or retroperitoneal fibrosis, papillary necrosis or large calculi

clinical presentation:

- clinical presentation may be acute or acute on chronic in patients with long standing calculi.

It may not always be associated with oliguria.

diagnostic criteria for hepatorenal syndrome

pre-renal

renal

failure

general:

- this form of ARF is the most common in ICUs

- indicates that the kidney malfunctions predominantly because of the systemic factors which

diminish renal blood flow and decrease GFR or by alteration of intraglomerular haemodynamics

pathophysiology:

- renal blood flow is decreased by:

(i) decreased cardiac output

(ii) hypotension

(iii) raised intraabdominal pressure (decompression should be considered when

the intrabdominal pressure is greater than 25-30mmHg above the pubis)

- in septic patients with hyperdynamic circulations there may be adequate global blood flow to the kidney but intrarenal shunting

away from the medullar causing medullary ischaemia or efferent arteriolar dilation thus decreasing GFR

- if the systemic cause of renal failure is rapidly removed renal function improves relatively rapidly

- several mechanisms are involved in the development of renal injury in pre-renal failure:

(i) ischaemia of the outer medulla with activation of tubuloglomerular feedback

(ii) tubular obstruction from casts of exfoliated cells

(iii) interstitial oedema secondary to back diffusion of fluid

(iv) humorally mediated afferent arteriolar renal vasoconstriction

(v) inflammatory response to cell injury and local release of mediators

(vi) disruption of normal cellular adhesion to the basement membrane

(vii) radical oxygen species induced apoptosis

(viii) mitogen-activated protein kinases-induced renal injury](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/medicineinmindmaps-150716131716-lva1-app6892/85/Medicine-in-Mind-Maps-10-320.jpg)

![acute right

ventricular

dysfunction

[created by

Paul Young

22/10/07]

causes

general

pathophysiology

imaging

biochemistry

- Right heart failure is characterized by a low cardiac output, hypotension, hepatic enlargement and raised JVP.

- Cardiogenic shock due to right ventricle failure has a mortality rate comparable to left ventricle failure

Right ventricular function:

- In systole, because of the constraints imposed by the pericardium, the high pressure in the left ventricle

and the heart's anatomical configuration, the septum intrudes into the right ventricular cavity.

- The right ventricle is better suited to volume overload than the left, but increased afterload is more detrimental.

- The low pressures in the right side of the heart arise as a result of the thin walled ventricle and highly compliant pulmonary circulation.

- The lack of myocardial bulk means that contractility cannot be maintained in the face of increased pulmonary resistance.

- In pulmonary hypertension, dilatation occurs as a compensating mechanism.

Right heart failure:

- In all cases, there is a critical point at which ventricular dilatation cannot compensate.

- Consequently, there is reversal of the ventricular septal pressure gradient, abnormal septal movement, rising atrial pressures and TR.

- The abnormal volume and pressure loading stress the right side of the heart, resulting in increased oxygen demand, decreased

coronary driving pressures and worsening right ventricle output. The global reduction in left sided preload contributes to systemic

hypotension exacerbated by septal dyskinesia and reversal of the interventricular dependence pressures. This in turn further lowers

coronary perfusion pressures. This vicious cycle has been termed auto-aggravation.

clinical

diagnosis

problems with clinical diagnosis:

(i) right ventricular failure may exist in the absence of peripheral oedema.

(ii) peripheral oedema is not discriminatory for right heart failure.

(iii) elevated jugular venous pressures and abnormal waveforms may be distorted by

mechanical ventilation, body habitus and lung hyperinflation in COPD patients.

(iv) signs such as hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnoea & hepatomegally are nonspecific.

CXR

- Changes in the pulmonary vasculature and the cardiac shadow may allow the diagnosis of underlying

pathology potentially associated with pulmonary hypertension and, by inference, right ventricular involvement

Echocardiography

- Echocardiography can show structural change, dynamic responses to intervention and

allows quantitative and qualitative measurements to refine the significance of findings.

- With transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) multiple measurements, ratios and estimates

have been used to assess quantitative and qualitative parameters including:

(i) tricuspid regurgitation;

(ii) long axis cavity size,

(iii) short axis septal kinetics,

(iv) apex loses triangle shape;

(v) right ventricular end-diastolic area/left ventricular end-diastolic area (>0.6 or >1);

(vi) left inferior hypokinesis;

(vii) right ventricle size in comparison to left ventricle;

(viii) right ventricular end diastolic volume diameter >30mm at level of mitral valve from left precordial view;

(ix) loss of inspiratory collapse of inferior vena cava

(x) dilation of pulmonary artery,

(xi) tricuspid regurgitation;

Right heart catherisation

- Right heart catheterisation and thermodilution are invasive but can provide nearly continuous values, in

contrast to other modalities, for right heart cardiac output and continuous right heart pressures.

- Natriuretic peptides induced by myocardial stress and dilatation are an attractive means to detect heart failure and to monitor

response to treatment. They have been used to stratify outcome in acute pulmonary embolismand in long-term follow-up for

patients with surgically corrected tetralogy of Fallot, and also as predictors of mortality in hypertension, renal failure, amyloidosis,

sepsis and diabetes.

- Plasma levels of natriuretic peptides have been shown to be proportional to the magnitude

of right ventricle dysfunction and correlate negatively with the ejection fraction.

- Levels vary in populations, sex, age groups and between various disease states. In the critically ill patient population natriuretic

peptides may be elevated due to underlying or coexisting heart disease or lung disease.

inotropes

& vasopressors

- No selective right heart inotrope exists.

- Augmentation of contractility can be achieved by b-mimetics, calcium sensitizers and phosphodiesterase

inhibitors. The problem is that without afterload manipulation, increasing right heart contractility and hence output,

increases myocardial oxygen consumption but without a systemic benefit.

general

treatment

aims

- The aim in the management of right ventricular dysfunction is to disrupt the cycle of auto-aggravation.

- For a given contractile state, reducing afterload will increase the ejection fraction.

- Similarly in a normal afterload state, augmentation of contractility raises the right ventricular ejection fraction.

- Volaemic status is difficult to judge. In a dilated decompensated ventricle with elevated atrial pressures, volume reduction is most likely to

improve the right ventricular ejection fraction. In the absence of elevated right atrial pressure then monitored volume challenges are justified.

- Reduction in myocardial oxygen demand or improvements in coronary perfusion must also be considered.

volume

optimisation

- Failure can be defined as the point at which the right ventricle fails to compensate for an increased ventricular volume, as each fibre

has an optimal stretch to allow maximal pressure generation, which, when exceeded, results in dilatation and eventually ventricular failure.

- Determination of preload is problematical but the presence of high right atrial filling pressures is indicative of elevated right ventricular pressures,

which extrapolates to a raised ventricular volume. This may not necessarily be true in all cases and depends on the compliance of the ventricle.

- In chronic elevation of right atrial pressures the pressure may be high, but this is a poor predictor of volume response, the patient may

therefore still be volume recruitable and sequential monitored fluid challenges are justified.

- The appearance of a dilated right ventricle with a reduced ejection fraction, however, should prompt a reduction in preload in a patient who is

not volume responsive (as defined by lack of alteration in heart rate, blood pressure, cardiac and urine output).

- The effect of therapy can be monitored by sequential echocardiography or by using right heart catheterization and, ideally, continuous measurement.

The converse is true though: sequential volume challenges monitored by pulmonary artery pressure changes in the absence of reversed right ventricle

interdependence will increase cardiac output, up to the individualized optimal filling point.

- The calcium sensitizing, lusitropic agent, levosimendan has been shown to provide a survival advantage in

heart failure trials. In a pilot study of levosimendan in early ARDS, Morelli et al. demonstrated that a reduction

in the pulmonary vascular resistance by levosimendan improved right ventricular function.

- Inotropes may provide a benefit in instances where ischaemia related to hypotension is a problem.

- They elevate the mean arterial pressure, coronary artery perfusion and may, consequently, reduce myocardial work.

- Vasotropic agents such as noradrenaline, phenylephrine and vasopressin may elevate diastolic pressures and

thus improve myocardial oxygenation. The benefit is lost once the right ventricle consumes more oxygen, to maintain

output, in the face of the elevated afterload.

- Phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as milrinone and amrinone inhibit the phosphodiesterase

enzymes responsible for cAMP/cGMP breakdown, augmenting myocardial contractility.

- The advantage of this drug class is that the mechanism is independent of b-adrenoceptor states and does not

increase myocardial oxygen demand. Nebulized milrinone, interestingly, has been shown to have an additive

effect with prostaglandin I2 in terms of pulmonary vasodilation.

- Hypoxaemia and hypercarbia worsen pulmonary artery pressures as does positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP), intrinsic PEEP

and high tidal volumes. Optimization of these variables needs to occur before pharmacological manipulation is undertaken.

afterload

reduction

General

- The poor contractile reserve of the right ventricle means that the primary modality for treatment of acute right ventricle

dysfunction secondary to elevated pulmonary artery pressures is by means of selective pulmonary vasodilation.

- Acutely, afterload reduction may be effected by using localized (inhaled) or systemic vasodilators. The consequences

of selected pulmonary vasodilation are of decreased resistance (and consequently afterload), improved VQ matching

and decreased arterial hypoxaemia.

Prostaglandins

- Prostaglandins can be given by inhalation, systemically or subcutaneously.

- The vasodilatory effects are mediated by nitric oxide release and interaction at a local level with the vascular endothelial smooth

muscle. Prostaglandin E1 systemically undergoes significant first pass pulmonary metabolism but with lower systemic pressures

and resistance, adversely altering the ventilation-perfusion matching and subsequently arterial oxygenation.

- When infused or as an aerosolized agent it is less effective than nitric oxide or aerosolized prostaglandin I2. Iloprost is

a stable carbacycline analogue of prostaglandin I2, a short acting natural prostaglandin. The vascular spillover of inhaled

iloprost, in combination with its prolonged plasma half-life, results in its systemic actions of lowered mean arterial pressure

and systemic vascular resistance.

- Nebulized prostaglandins are attractive in that they have limited systemic effects, are cheap and do not require specialized

delivery systems. The particle size, however, cannot easily be controlled and hence inefficiency of delivery may be significant

resulting in higher doses with potential systemic spillover.

Nitric oxide

- Inhaled nitric oxide (iNO), by virtue of its localized vascular endothelial action, through cGMP generation and its interaction

with calcium gated potassium channels and protein kinase G as well as cGMP independent paths, acts as pulmonary vasodilator.

Its effects are limited to the ventilated areas of the lung, with minimal

systemic overspill because of its rapid inactivation by haemoglobin

- No outcome benefit has yet been demonstrated in responders,

however, although oxygenation and pulmonary resistance do improve.

- Withdrawal of nitric oxide has been shown to result in rebound pulmonary hypertension

- Inhaled nitric oxide requires specialized delivery systems and the side-effect profile is significant, with platelet dysfunction,

myocardial depression, renal failure and the formation of toxic compounds such as peroxynitrites. The side effects are dose

dependent and although recommended doses are under 10 ppm quantities up to 80 ppm have been used.

Sildenafil

- Sildenafil is a phosphodiesterase V enzyme, whose inhibition prolongs the

action of cGMP, with the overall effect of reducing pulmonary vascular tone.

- Tadalafil and vardenafil, members of the same class of phosphodiesterase inhibitors, have similar effects but of different

magnitude and duration. Sildenafil has been evaluated in decompensated right ventricular dysfunction, but its lack of an

intravenous preparation limits its use.

Systemic vasodilators

- Systemic vasodilators such as sodium nitroprusside, glyceryl trinitrate and hydralazine all reduce pulmonary afterload but at the expense

of systemic hypotension,decreasing coronary ostial perfusion pressures and potentially leading to a deleterious preload reduction,

exacerbating the dysfunction of the right ventricle, already compromised because of high right ventricular end diastolic pressure, through

ischaemia. Hence selective pulmonary vasodilators are more desirable in reducing afterload than global agents.

Recombinant BNP

- Neseritide is a recombinant version of BNP. Its actions, when infused, are identical to the in-vivo effects of BNP (natriuresis,

sympathetic dampening and suppression of the renin- angiotensin axis by increasing cGMP). It reduces both preload and afterload,

consequently improving cardiac output without inotropy. Concerns exist over the decreased 30-day survival and its adverse impact

on renal function.

- In addition the systemic side effect can be that of hypotension and subsequently, decreased coronary perfusion pressures.

- To date it has not been evaluated in pure right heart failure.

Mechanical

ventilation

& PEEP

- The distending alveolar pressure, when transmitted through the pulmonary capillary bed, determines the opening pressure

of the pulmonary artery valve.

- The greater the tidal volume the greater the impedance and hence the myocardial power generation has to be increased.

- Pleural pressure is transmitted to the myocardium because of the constricting pericardium, which limits the extent of

ventricular distension. Thus for an increase in pleural pressures a consequently higher preload is required to maintain the

right ventricular end diastolic volume

- A right ventricular friendly strategy is to set PEEP to limit gas trapping with prolonged expiratory times and to utilize as low a tidal

volume and respiratory rate as possible without deleterious ventilatory consequences

Surgical,

interventional

and right

ventricular

support

- The management of acute right ventricular infarction should follow standard guidelines for the reperfusion of occluded coronary arteries.

- Pacing, where indicated, has been shown to reduce mortality in biventricular failure and

should be considered in order to restore atrioventricular synchrony to ensure adequate preload

- Right ventricular assist devices may be appropriate in particular circumstances](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/medicineinmindmaps-150716131716-lva1-app6892/85/Medicine-in-Mind-Maps-11-320.jpg)

![additional

indices in

analysis

of metabolic

acidosis

[created by

Paul Young

13/12/07]

urinary

anion

gap

General

- The cations normally present in urine are Na+, K+, NH4+, Ca++ and Mg++.

- The anions normally present are Cl-, HCO3-, sulphate, phosphate and some organic anions.

- Only Na+, K+ and Cl- are commonly measured in urine so the other charged

species are the unmeasured anions (UA) and cations (UC).

Urinary Anion Gap = [Na+]+ [K+] - [Cl-]

Clinical Use

- The urinary anion gap can help to differentiate between GIT and renal causes of a

hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis.

- It has been found experimentally that the Urinary Anion Gap (UAG) provides a rough

index of urinary ammonium excretion. Ammonium is positively charged so a rise in its

urinary concentration (ie increased unmeasured cations) will cause a fall in UAG

Pathophysiology

- Hyperchloraemic acidosis can be caused by:

(i) Loss of base via the kidney (eg renal tubular acidosis)

(ii) Loss of base via the bowel (eg diarrhoea).

(iii) Gain of mineral acid (eg HCl infusion).

- If the acidosis is due to loss of base via the bowel then the kidneys can respond

appropriately by increasing ammonium excretion to cause a net loss of H+ from the body.

The UAG would tend to be decreased, That is: increased NH4+ (with presumably

increased Cl-) => increased UC =>decreased UAG.

- If the acidosis is due to loss of base via the kidney, then as the problem is with the kidney

it is not able to increase ammonium excretion and the UAG will not be increased.

- Experimentally, it has been found that patients with diarrhoea severe enough to cause

hyperchloraemic acidosis have a negative UAG (average value -27 +/- 10 mmol/l) and

patients with acidosis due to altered urinary acidification had a positive UAG.

Osmolar

Gap

general

- An osmole is the amount of a substance that yields, in ideal solution, that number of

particles (Avogadro's number) that would depress the freezing point of the solvent by 1.86K

- Osmolality is measured in the laboratory by machines called osmometers. The units of

osmolality are mOsm/kg of solute

- Osmolarity is calculated from a formula which represents the solutes which under ordinary

circumstances contribute nearly all of the osmolality of the sample. There are many such

formulae which have been used. One is:

Calculated osmolarity = (2 x [Na+]) + [glucose] + [urea]

- The osmolar gap is the difference between the 2 values: the (measured) osmolality and

the (calculated) osmolarity (which is calculated):-

Osmolar gap = Osmolality - Osmolarity

- An osmolar gap > 10 mOsm/l is often stated to be abnormal.

Importance of the type of osmometer

- Only osmometers using freezing point depression method should be used for determining

this calculation because they are the only type of osmometer that can detect all the volatile

alcohols which can abnormally increase the osmolar gap. Vapour pressure osmometers can't do this

Significance of an elevated osmolar gap

- An elevated osmolar gap provides indirect evidence for the presence of an abnormal

solute which is present in significant amounts. To have much effect on the osmolar gap,

the substance needs to have a low molecular weight and be uncharged so it can be present

in a form and in a concentration (measured in mmol/l) sufficient to elevate the osmolar

gap.

- Ethanol, methanol & ethylene glycol are three such solutes that, when present in

appreciable amounts, will cause an elevated osmolar gap. If you suspect that your patient

may have ingested one of these substances than you should determine the osmolar gap.

- if the ethanol levels are measured they can be added to the calculated osmolarity to

exclude the presence of an additional contributer to the osmolar gap. [NB: To convert

ethanol levels in mg/dl to mmol/l divide by 4.6. For example, an ethanol level of 0.05% is

50mg/dl. Divide by 4.6 gives 10.9mmols/l]

delta

ratio

Definition

- The Delta Ratio is sometimes useful in the assessment of metabolic acidosis.

- The Delta Ratio is defined as:

Delta ratio = (Increase in Anion Gap / Decrease in bicarbonate)

Use

- In order to understand this, consider the following:

- If one molecule of metabolic acid (HA) is added to the ECF and dissociates, the one H+

released will react with one molecule of HCO3- to produce CO2 and H2O. This is the

process of buffering. The net effect will be an increase in unmeasured anions by the one

acid anion A- (ie anion gap increases by one) and a decrease in the bicarbonate by one.

- if all the acid dissociated in the ECF and all the buffering was by bicarbonate, then the

increase in the AG should be equal to the decrease in bicarbonate so the ratio between

these two changes (which we call the delta ratio) should be equal to one. The delta ratio

quantifies the relationship between the changes in these two quantities.

- the above assumptions about all buffering occurring in the ECF and being totally by

bicarbonate are not correct. Fifty to sixty percent of the buffering for a metabolic acidosis

occurs intracellularly. This amount of H+ from the metabolic acid (HA) does not react

with extracellular HCO3- so the extracellular [HCO3-] will not fall as far as originally

predicted. The acid anion (ie A-) however is charged and tends to stay extracellularly so

the increase in the anion gap in the plasma will tend to be as much as predicted.

- Overall, this significant intracellular buffering with extracellular retention of the

unmeasured acid anion will cause the value of the delta ratio to be greater than one in a

high AG metabolic acidosis.

Sources of error:

- Inaccuracies can occur for several reasons, for example:

(i) Calculation requires measurement of 4 electrolytes, each with a measurement error

(ii) Changes are assessed against 'standard' normal

values for both anion gap and bicarbonate concentration.

Assessment

< 0.4

- Hyperchloraemic normal anion gap acidosis

- A low ratio occurs with hyperchloraemic normal anion gap acidosis. The reason here is

that the acid involved is effectively hydrochloric acid (HCl) and the rise in plasma

[chloride] is accounted for in the calculation of anion gap (ie chloride is a 'measured

anion').

- The result is that the 'rise in anion gap' (the numerator in the delta ration calculation)

does not occur but the 'decrease in bicarbonate' (the denominator) does rise in numerical

value.

- The net of of both these changes then is to cause a marked drop in delta ratio,

commonly to < 0.4

0.4 - 0.8

- Consider combined high AG & normal AG acidosis BUT note

that the ratio is often <1 in acidosis associated with renal failure

1 to 2

- Usual for uncomplicated high-AG acidosis.

- Lactic acidosis: average value 1.6

- DKA more likely to have a ratio closer to 1 due to urine ketone loss

(esp if patient not dehydrated)

> 2

- A high delta ratio can occur in the situation where the patient had quite an elevated

bicarbonate value at the onset of the metabolic acidosis. Such an elevated level could be

due to a pre-existing metabolic alkalosis, or to compensation for a pre-existing

respiratory acidosis (ie compensated chronic respiratory acidosis).

anion

gap

General:

- The term anion gap (AG) represents the concentration of all the unmeasured anions in

the plasma. The negatively charged proteins account for about 10% of plasma anions and

make up the majority of the unmeasured anion represented by the anion gap under normal

circumstances.

- the AG = [Na+] + [K+] - [Cl-] - [HCO3-] and a the upper range of normal is about 15

Major Clinical Uses of the Anion Gap

(i) To signal the presence of a metabolic acidosis and confirm other findings

- If the AG is greater than 30 mmol/l, than it invariably means that a metabolic acidosis is

present. If the AG is in the range 20 to 29 mmol/l, than about one third of these patients

will not have a metabolic acidosis.

(ii) Help differentiate between causes of a metabolic acidosis:

-high anion gap versus normal anion gap metabolic acidosis.

The effect of albumin & phosphate

- Albumin is the major unmeasured anion and contributes almost the whole of the value

of the anion gap.

- Every one gram decrease in albumin will decrease anion gap by 2.5 to 3 mmoles. A

normally high anion gap acidosis in a patient with hypoalbuminaemia may appear as a

normal anion gap acidosis.

- This is particularly relevant in Intensive Care patients where lower albumin levels are

common.

- the 'normal anion gap depends on the serum phosphate and the serum albumin.

anion gap = 0.2 x [albumin] (g/L) + 1.5 x [phosphate] (mmol/L)

metabolic acidosis with increased anion gap:

Methanol, metformin

Uraemia

DKA

Phenformin, paraldehyde, propylene glycol, pyroglutamic acidosis

Iron, isoniazid

Lactic acidosis

Ethanol ketoacidosis, ethylene glycol

Salicylates, starvation ketoacidosis, solvent

metabolic acidosis with normal anion gap:

Ureteroenterostomy (K+ decreased)

Small bowel fistula (K+ decreased)

Extra chloride (K+ increased)

Diarrhoea (K+ decreased)

Carbonic anhydrase (K+ decreased)

Renal tubular acidosis (K+ decreased - type 1)

Addison's disease (K+ increased)

Pancreatic fistula (K+ decreased)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/medicineinmindmaps-150716131716-lva1-app6892/85/Medicine-in-Mind-Maps-12-320.jpg)

![adrenal

insufficiency

in sepsis &

septic shock

[created by

Paul Young

10/12/07]

guidelines

- international guidelines recommend the use of low dose corticosteroids for the treatment

of septic shock. However, there are some discrepancies in these recommendations.

(i) the Surviving Sepsis Campaign recommended the use of stress dose of corticosteroids

for septic shock regardless of adrenal function.

(ii) the American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force recommended that stress

dose of corticosteroids should be used only in refractory septic shock or in adrenal

insufficient patients.

mechanisms

of action of

corticosteroids

genomic actions

- Cells from most tissues are responsive to corticosteroids, which freely cross cell

membranes. The glucocorticoids receptor forms an inactive intracytosolic complex with

chaperone proteins like heat shock protein (HSP) 40, HSP56, HSP70, and HSP90,

immunophillins, P23, and other unknown proteins

- The receptor contains three domains: one binds corticosteroids, one binds to DNA, also

involved in dimerization; and one activates the promoters within the genes.