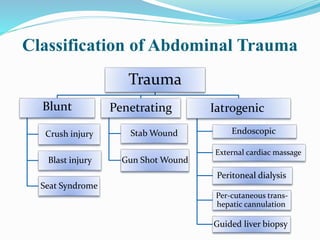

The document provides an overview of abdominal trauma, including its classification, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Some key points:

- Abdominal injury is a major contributor to trauma deaths and frequently occurs with multiple injuries, posing management challenges.

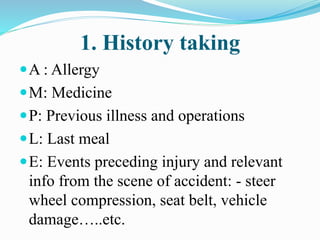

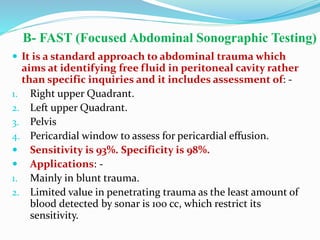

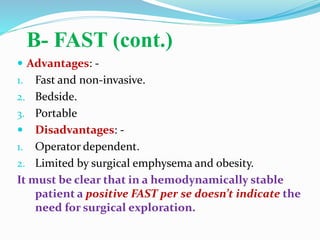

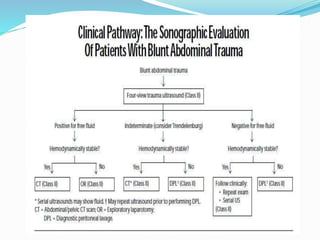

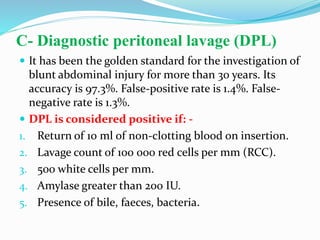

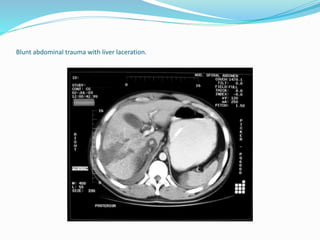

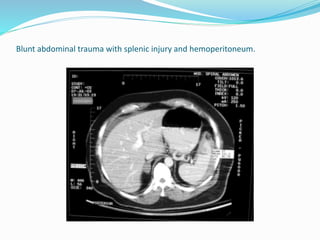

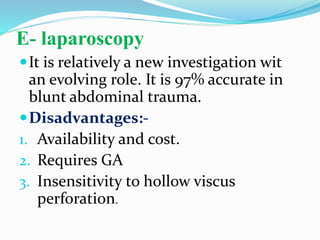

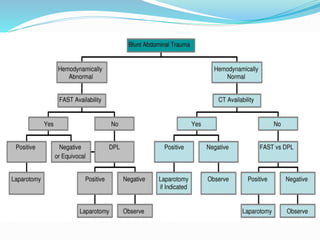

- Diagnosis involves history, physical exam, and directed investigations like FAST ultrasound, CT scan, DPL, and laparoscopy to identify need for surgery.

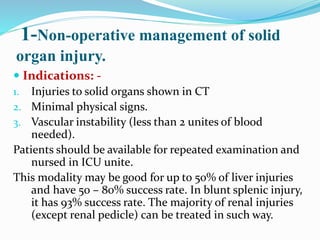

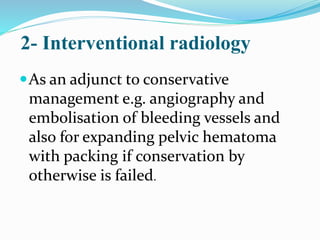

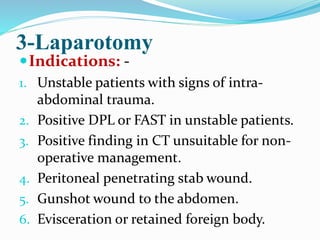

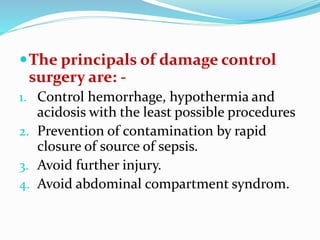

- Treatment depends on injury type and stability, ranging from non-operative management of solid organ injuries to laparotomy adhering to damage control principles.

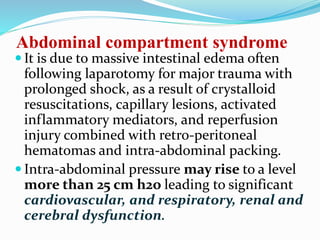

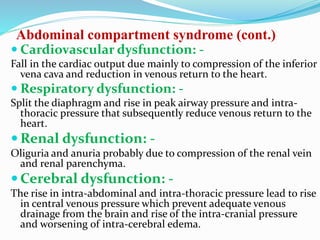

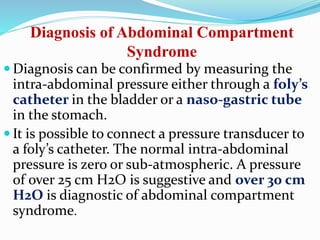

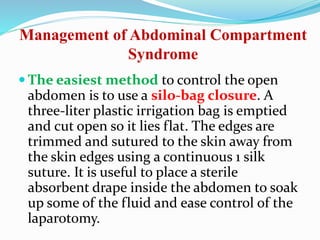

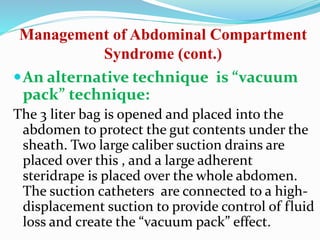

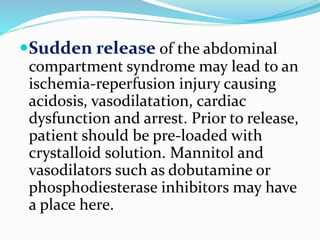

- Abdominal compartment syndrome can arise from massive intestinal edema and require decompression techniques like silo bag closure or vacuum pack.