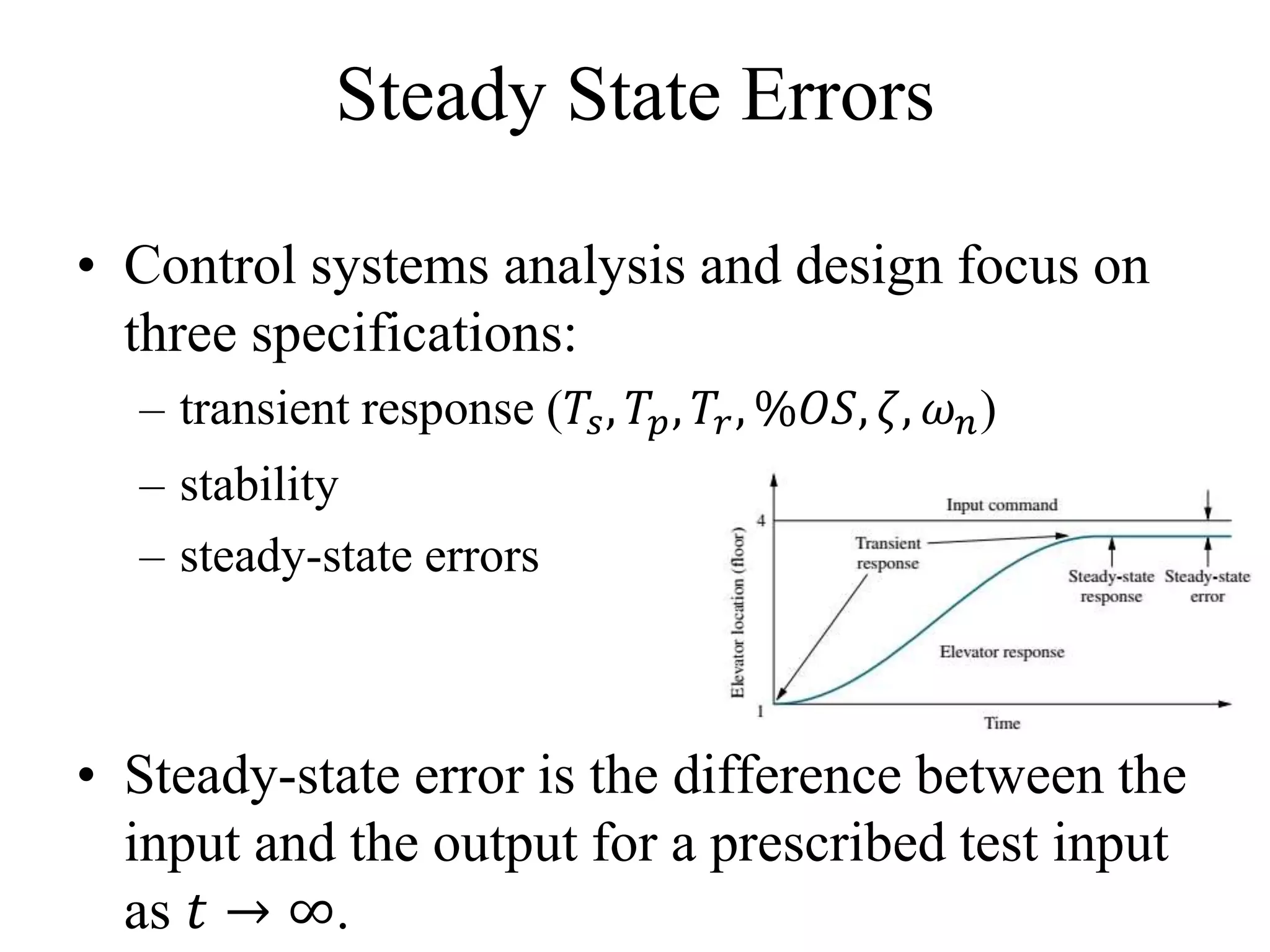

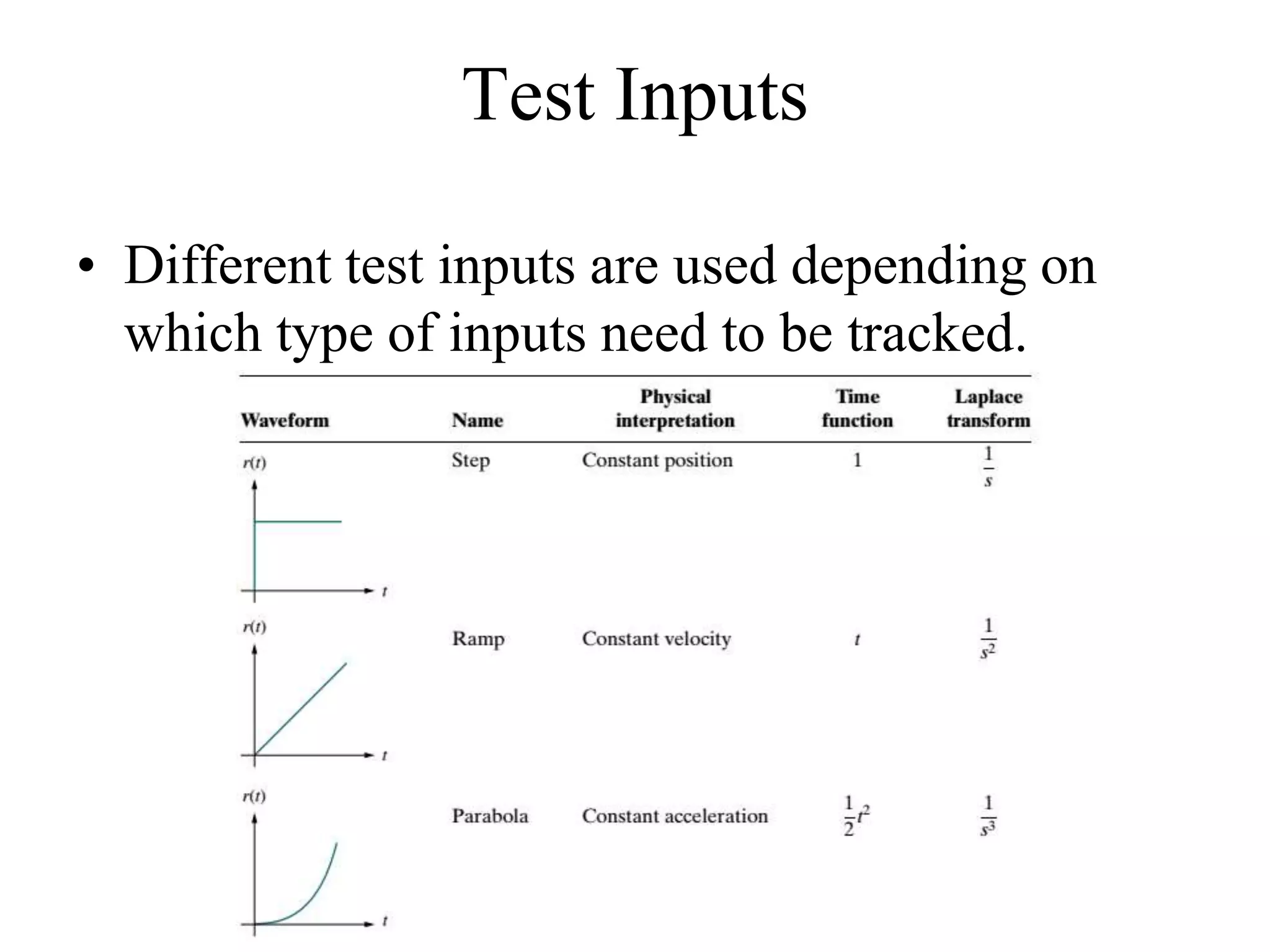

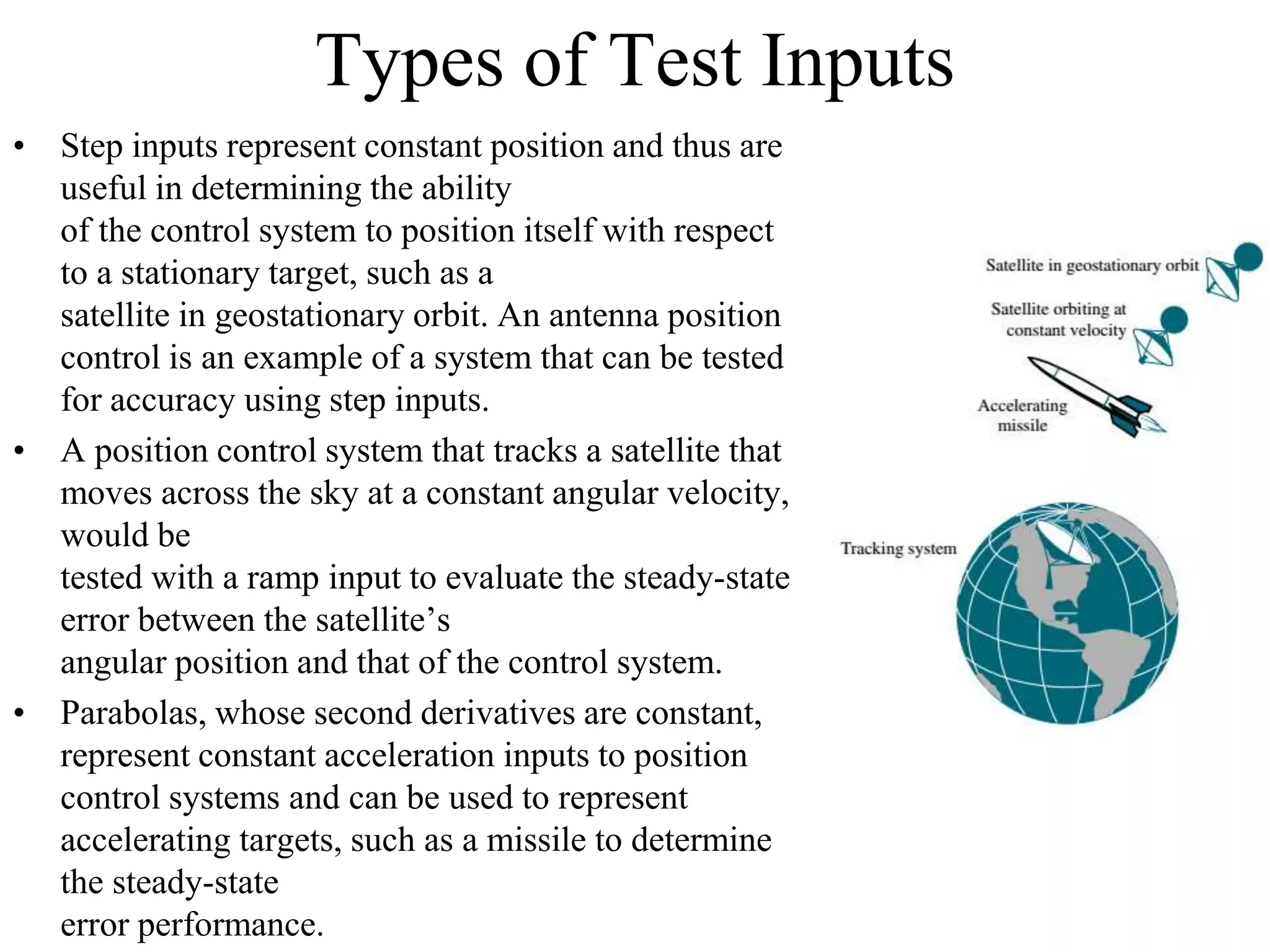

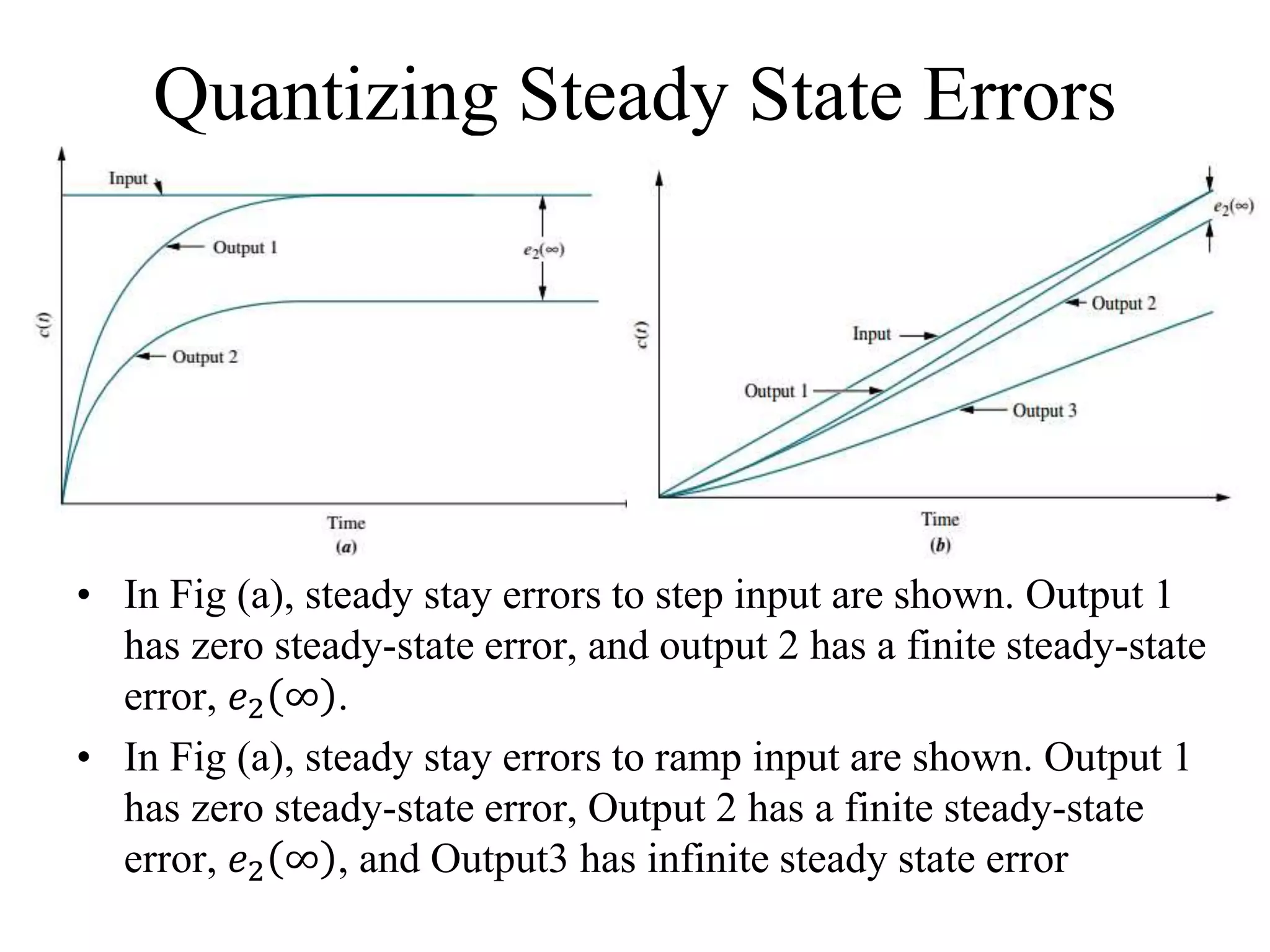

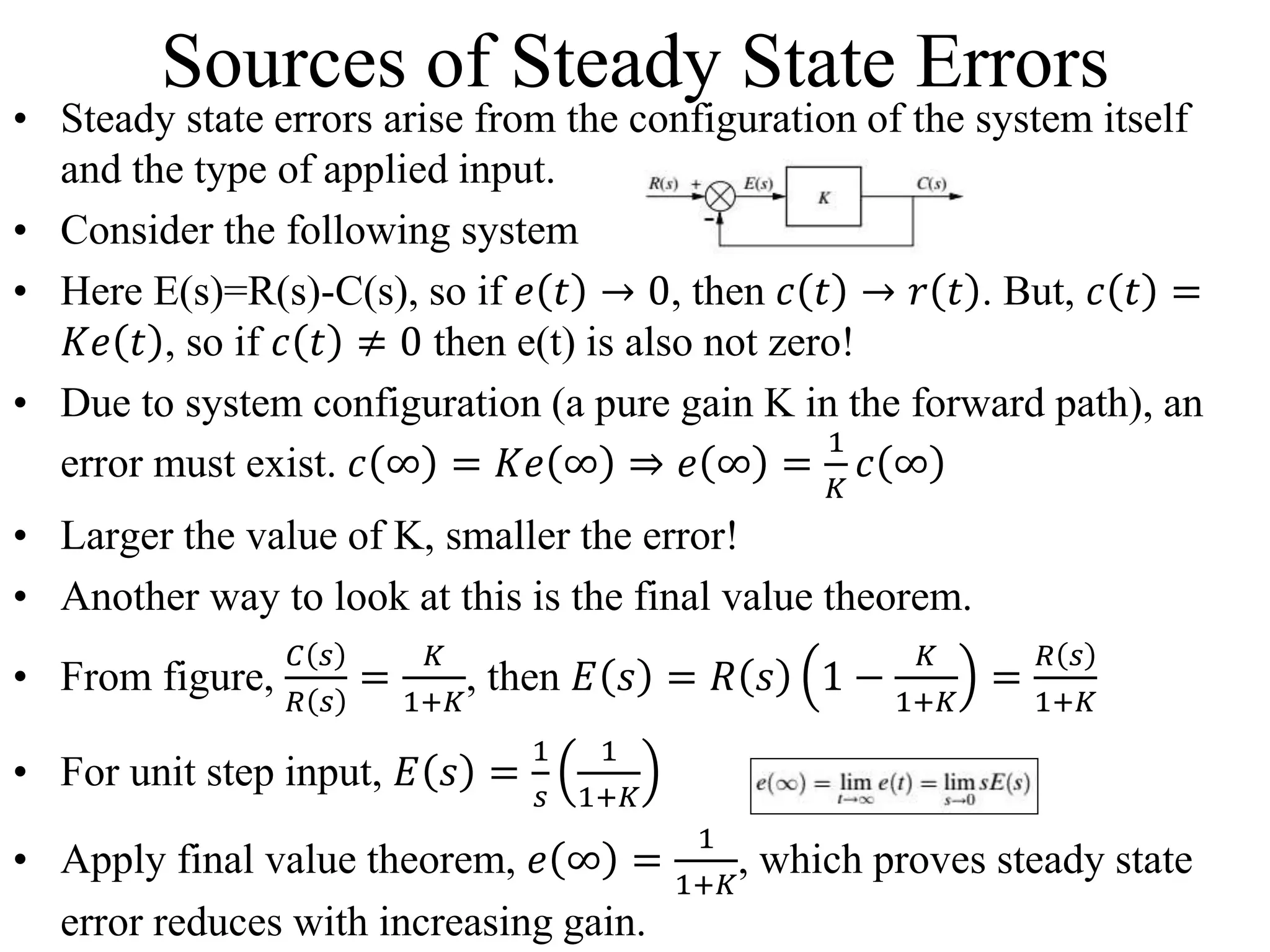

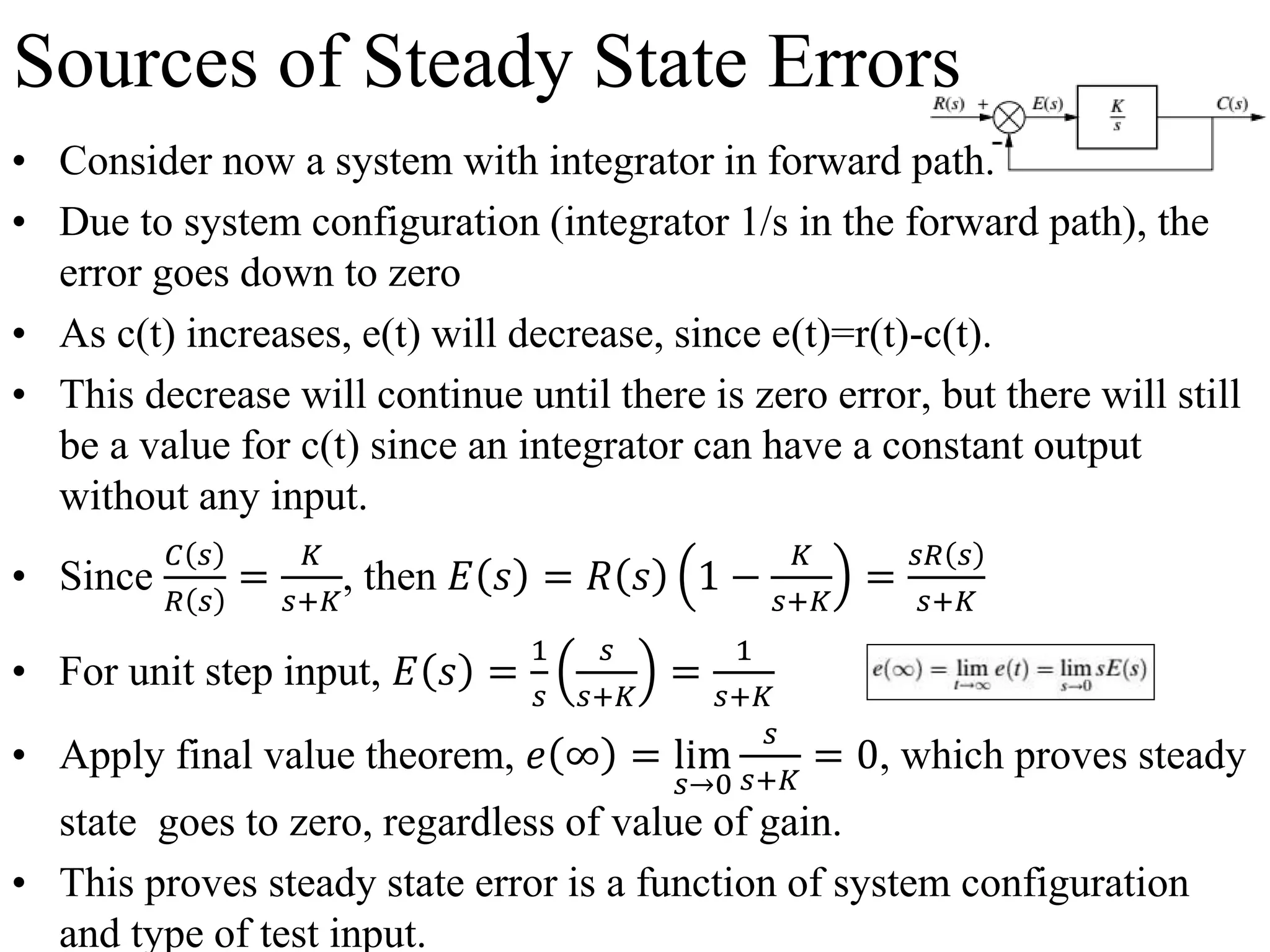

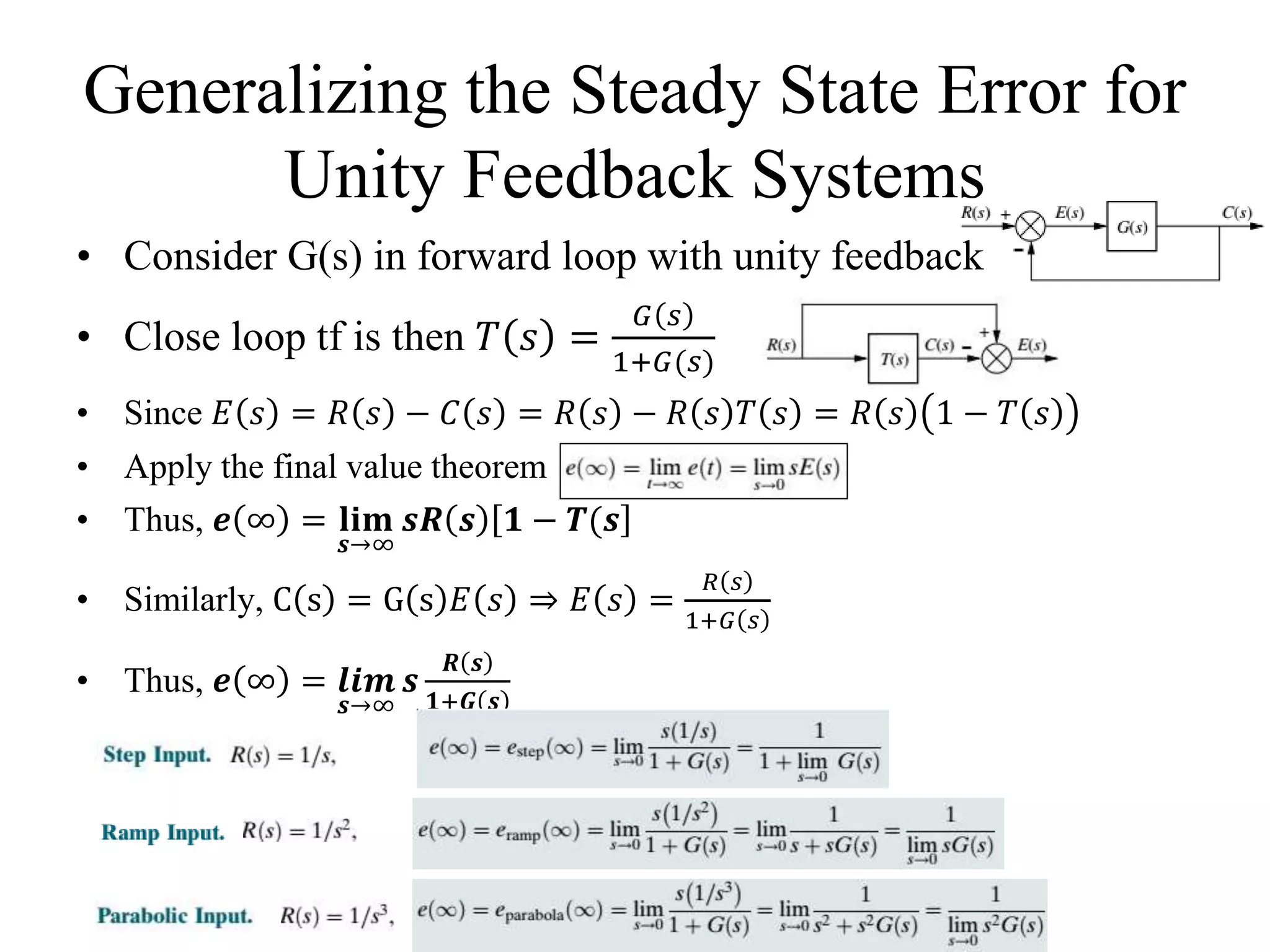

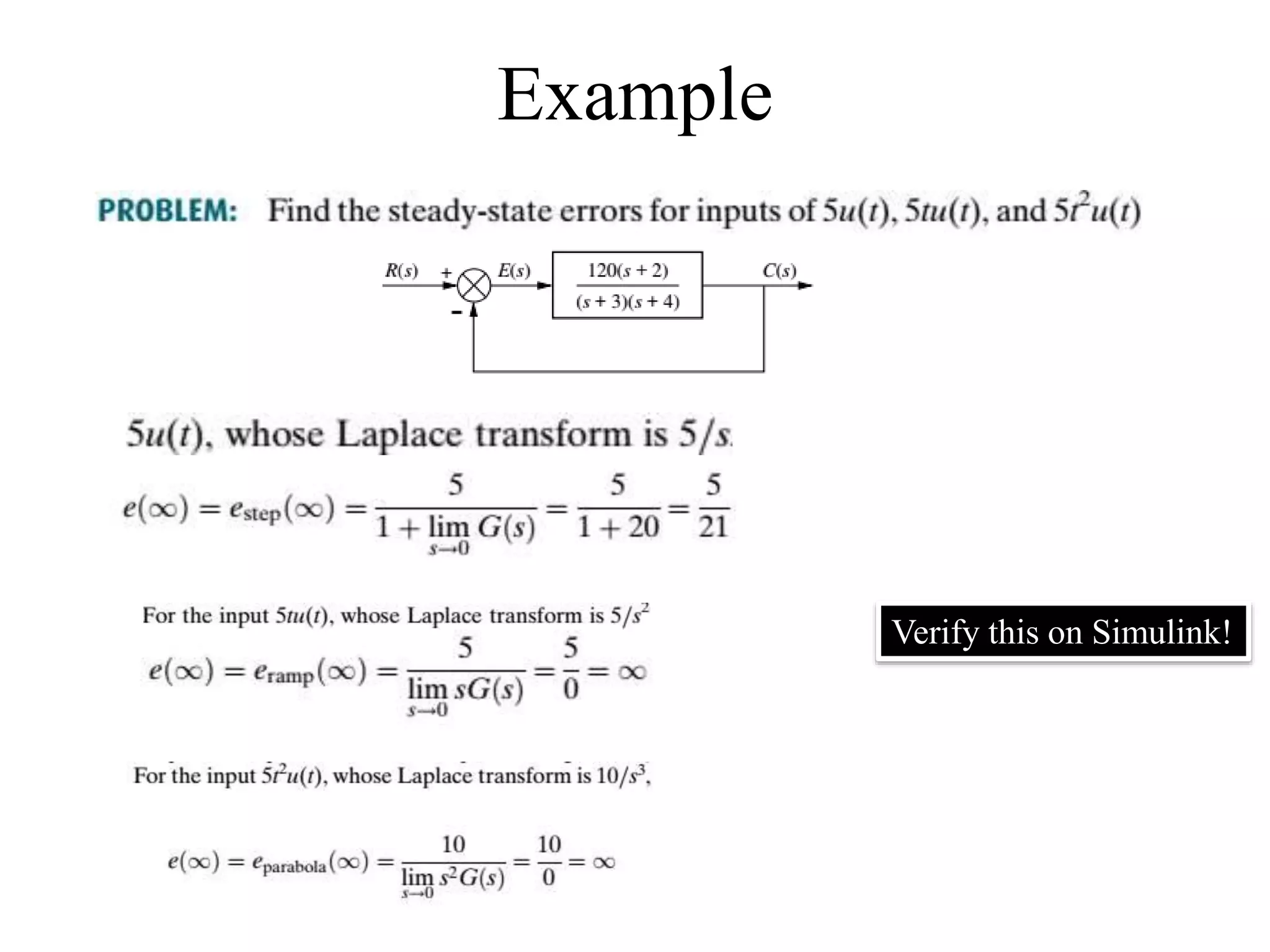

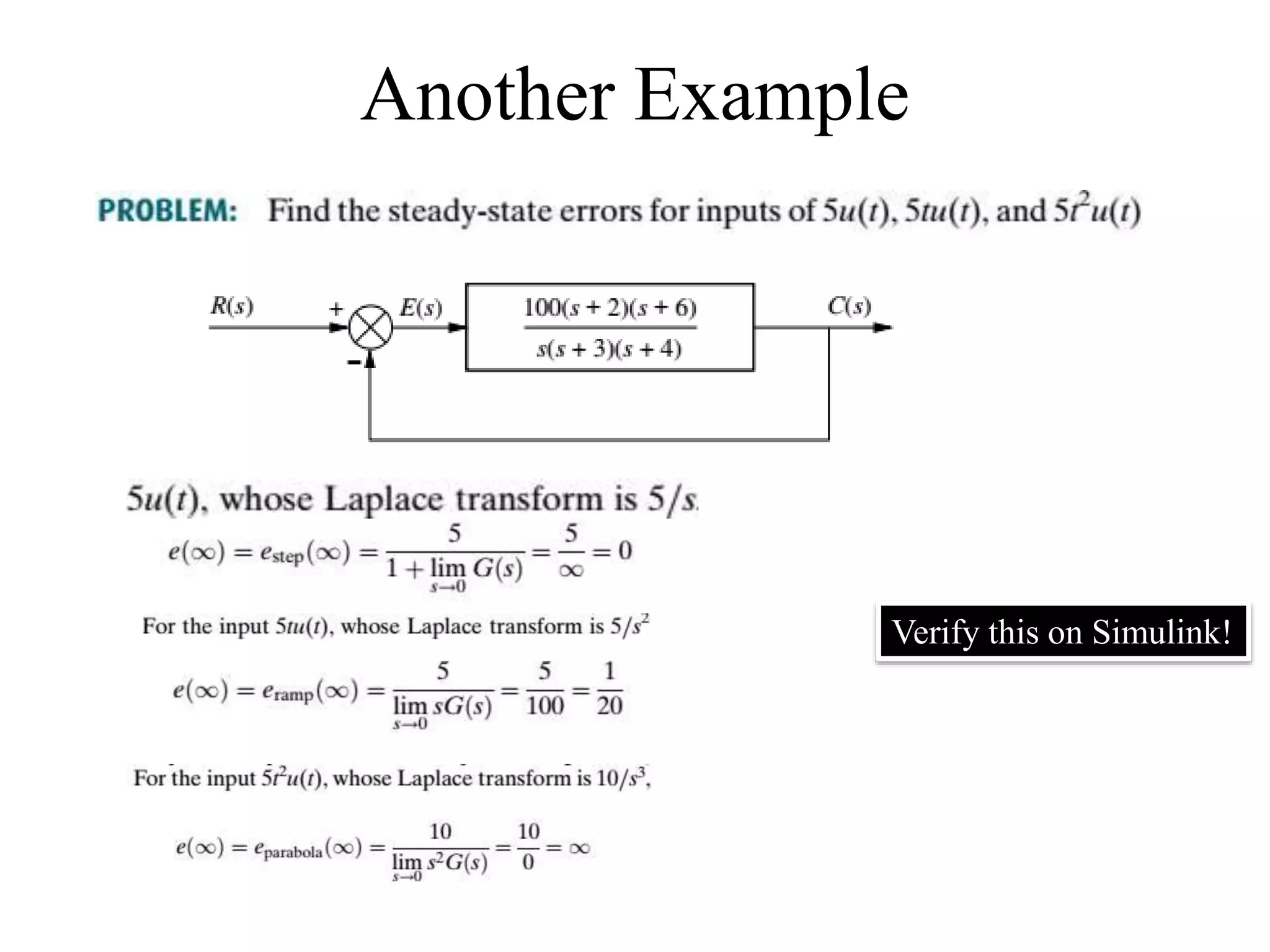

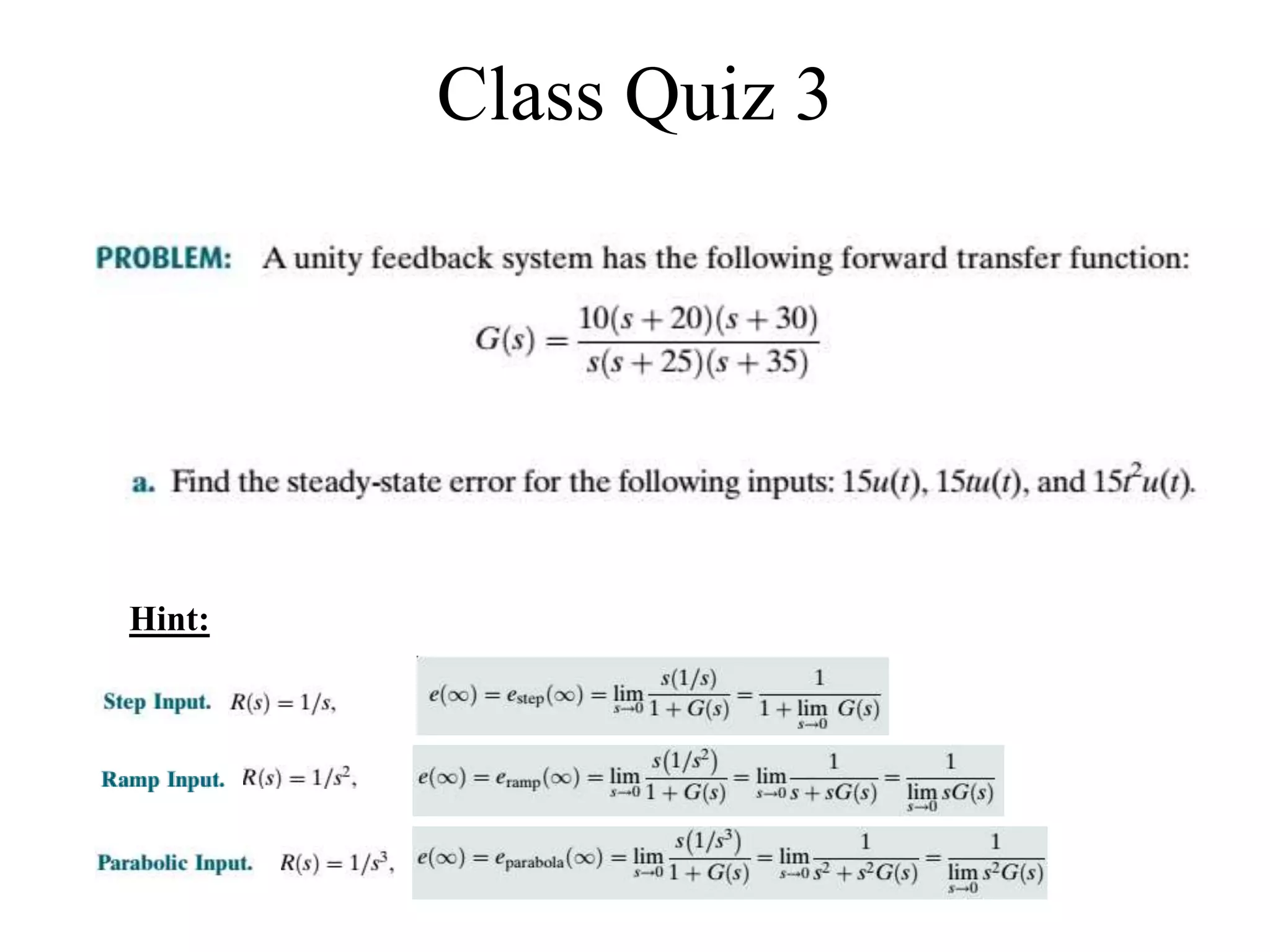

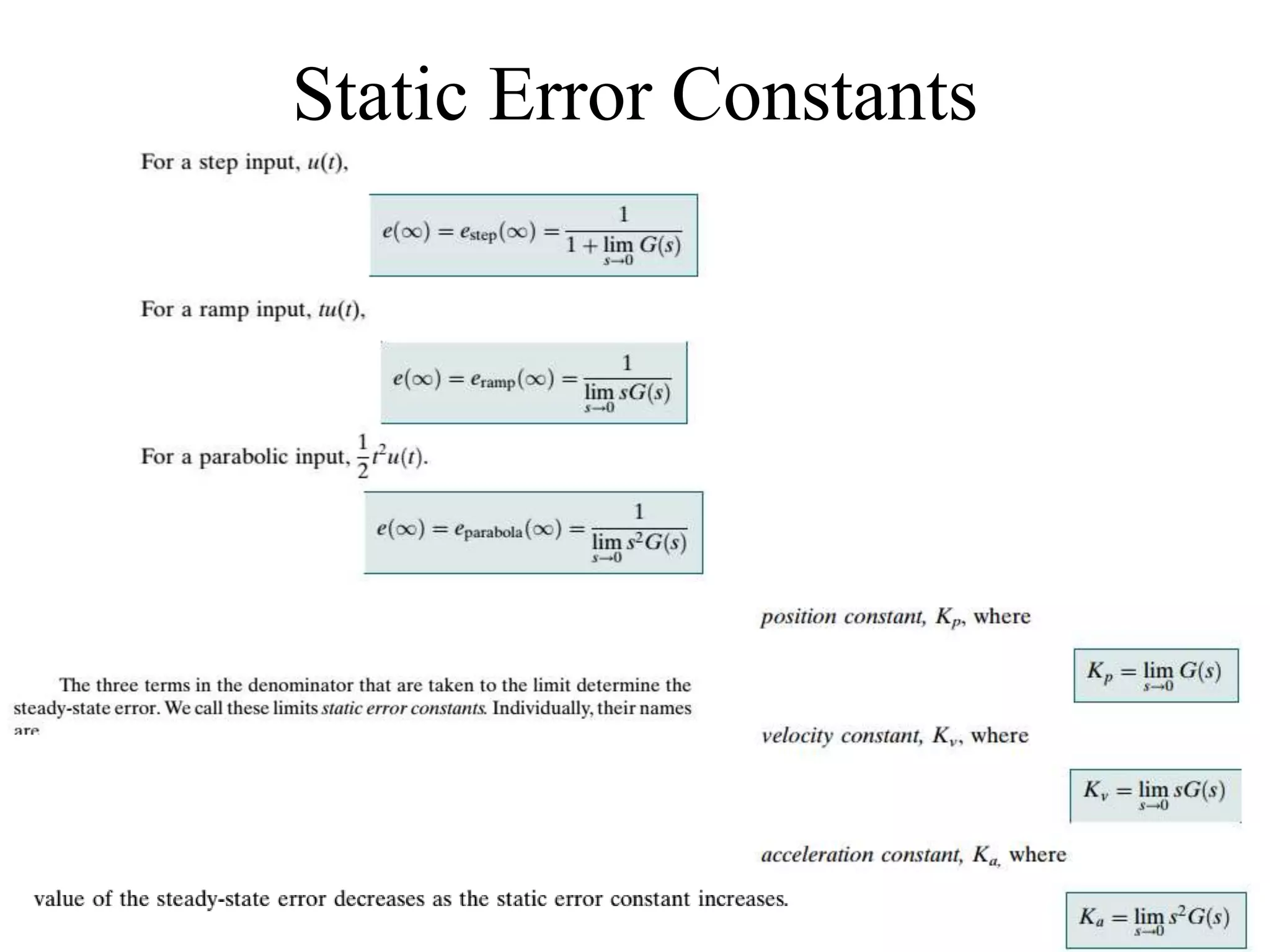

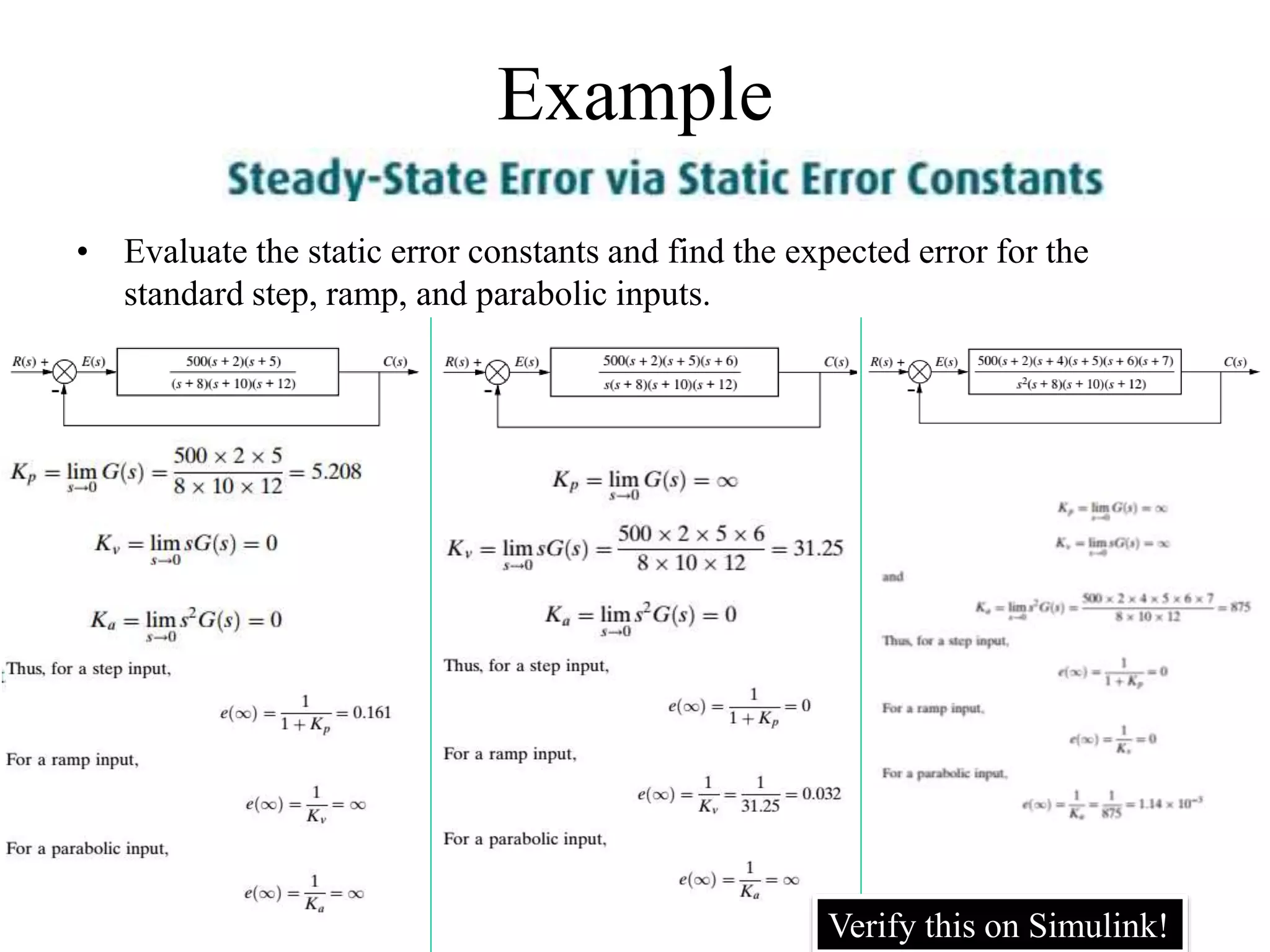

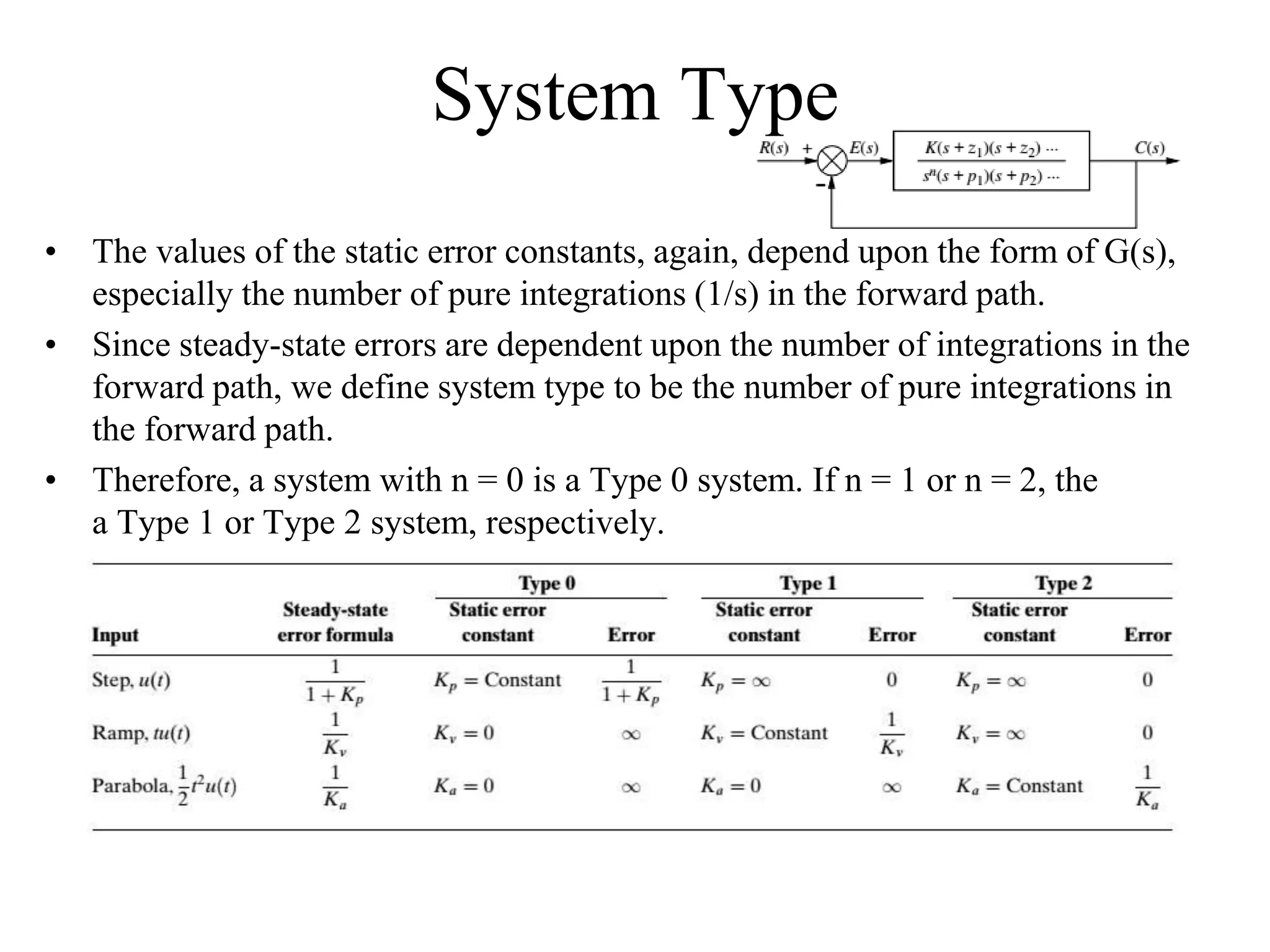

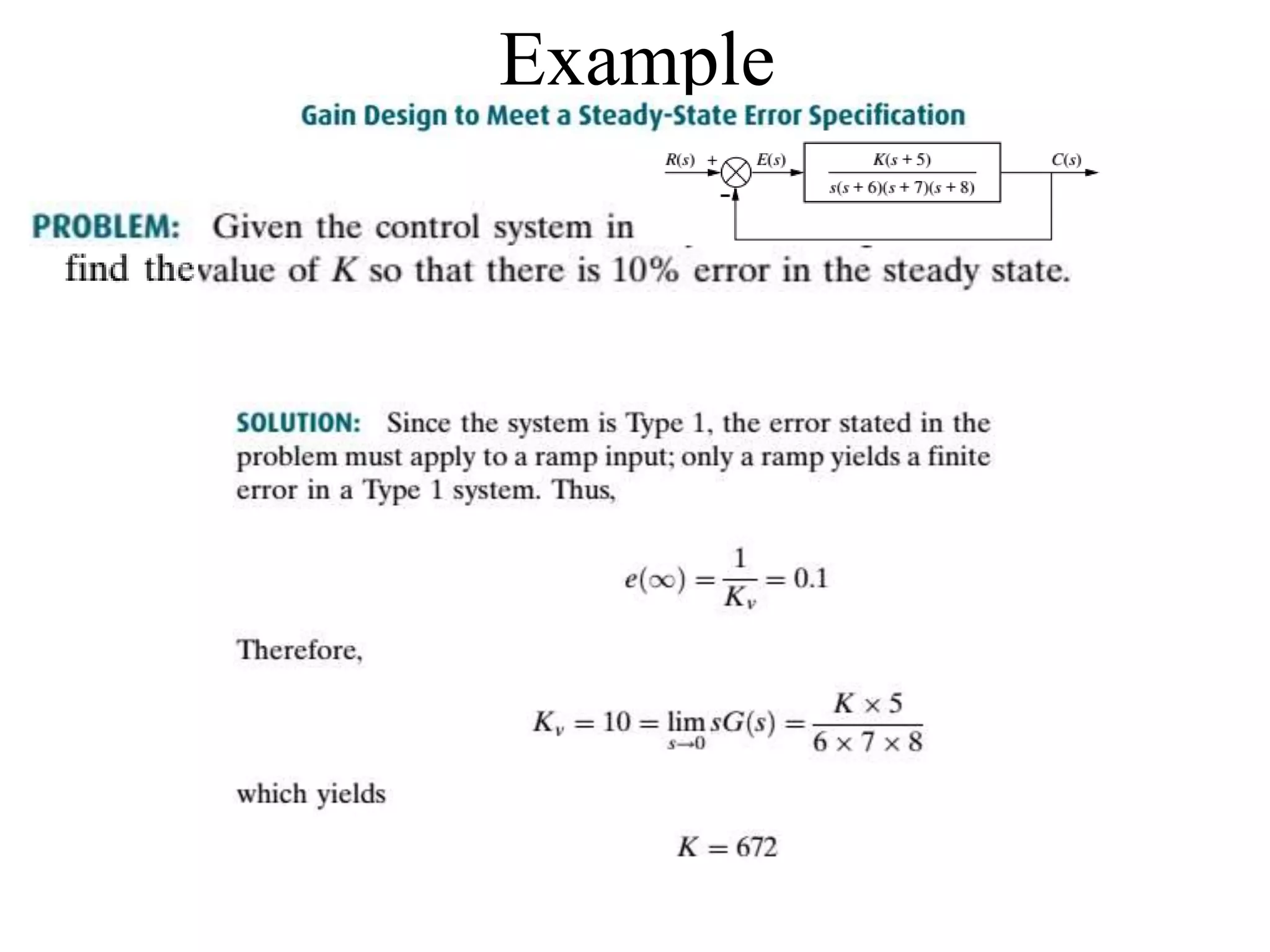

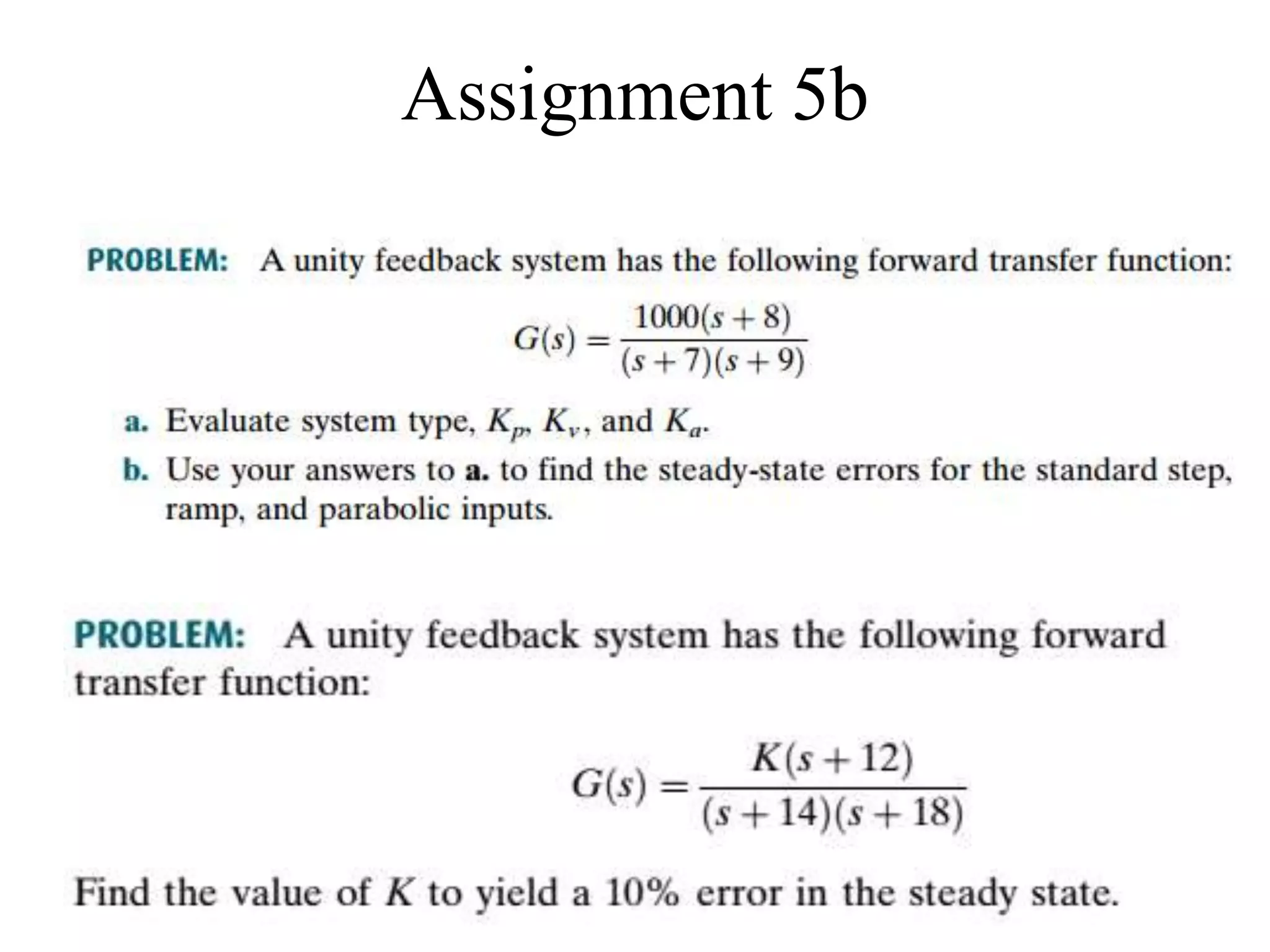

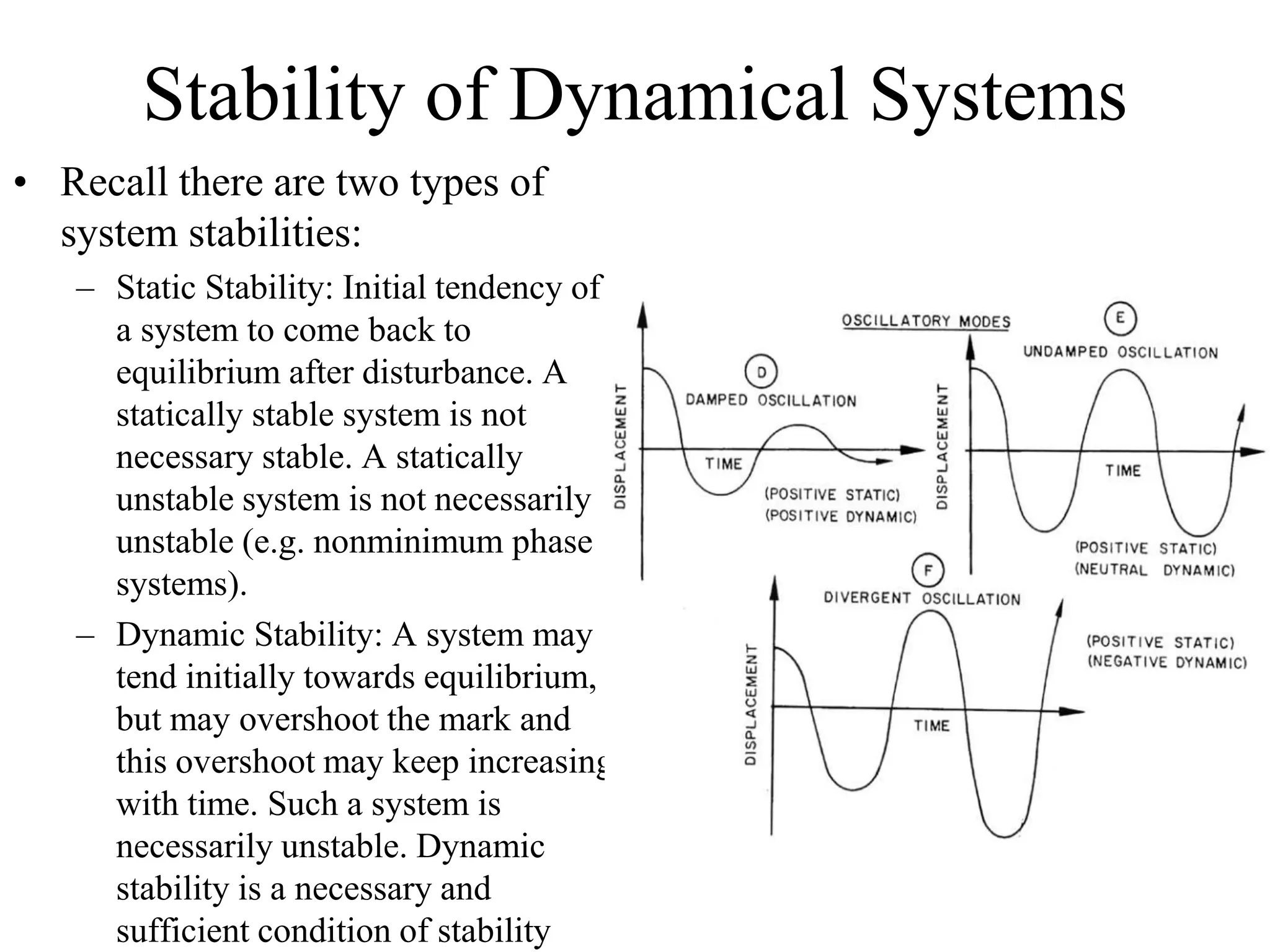

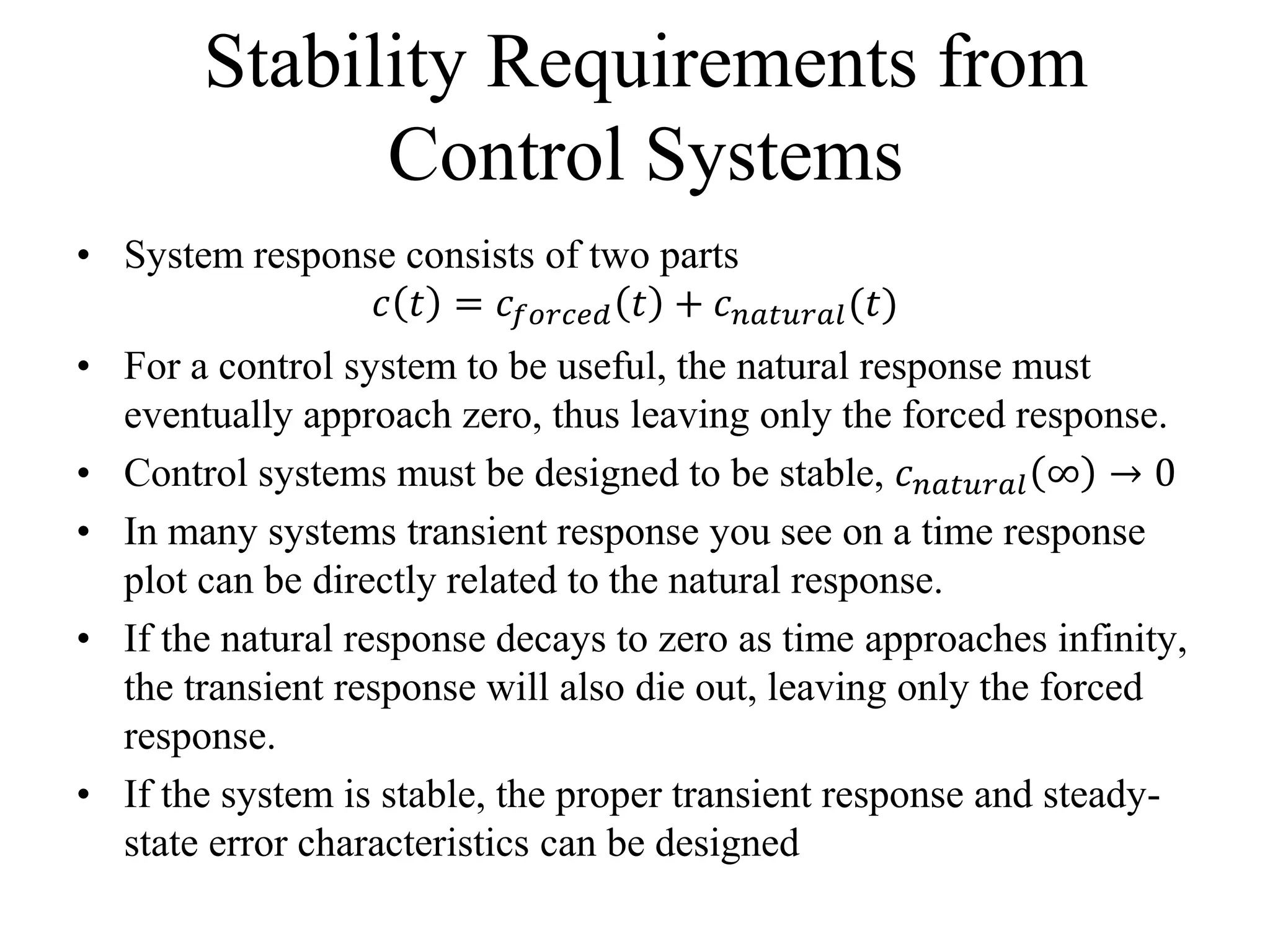

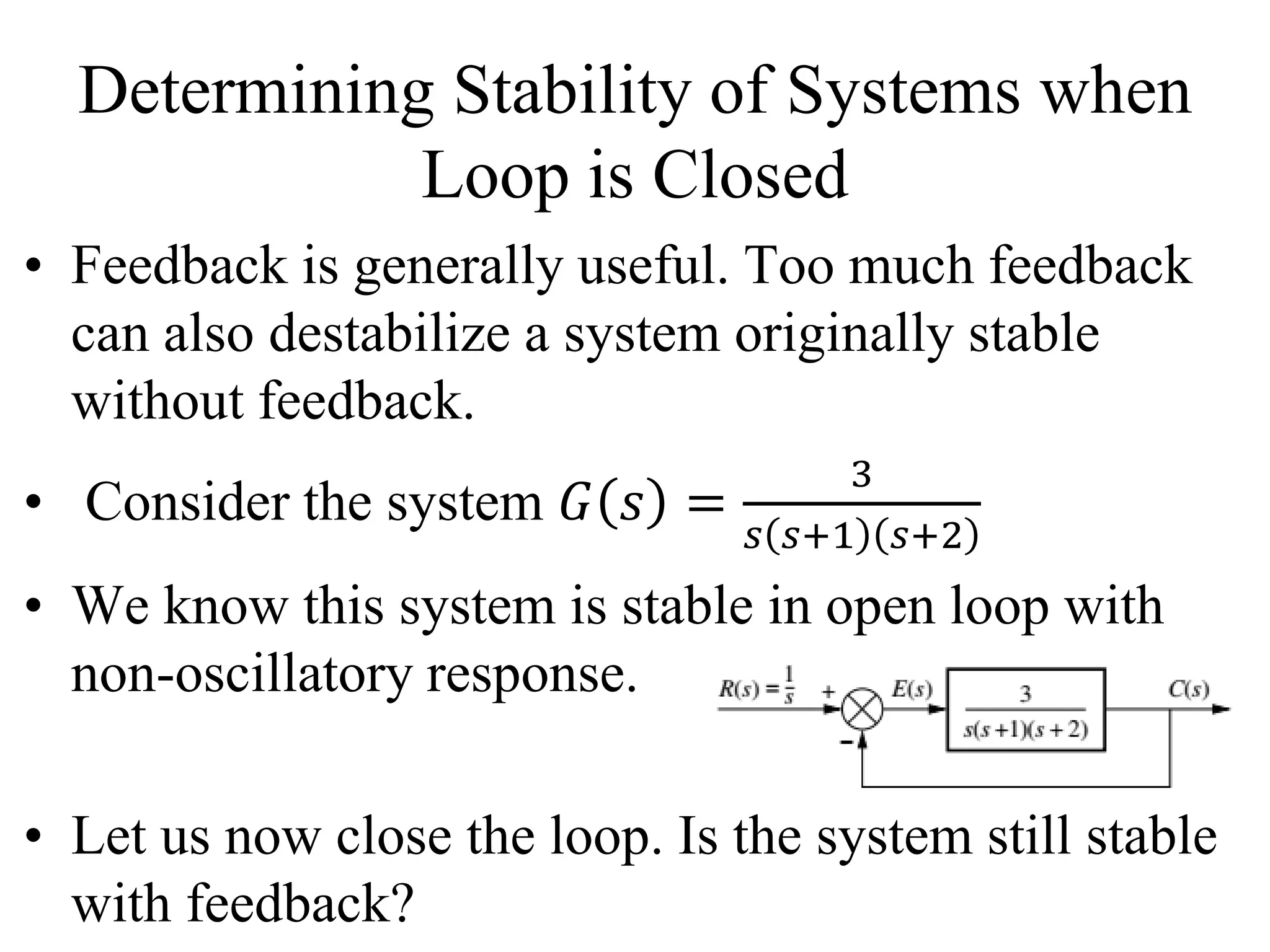

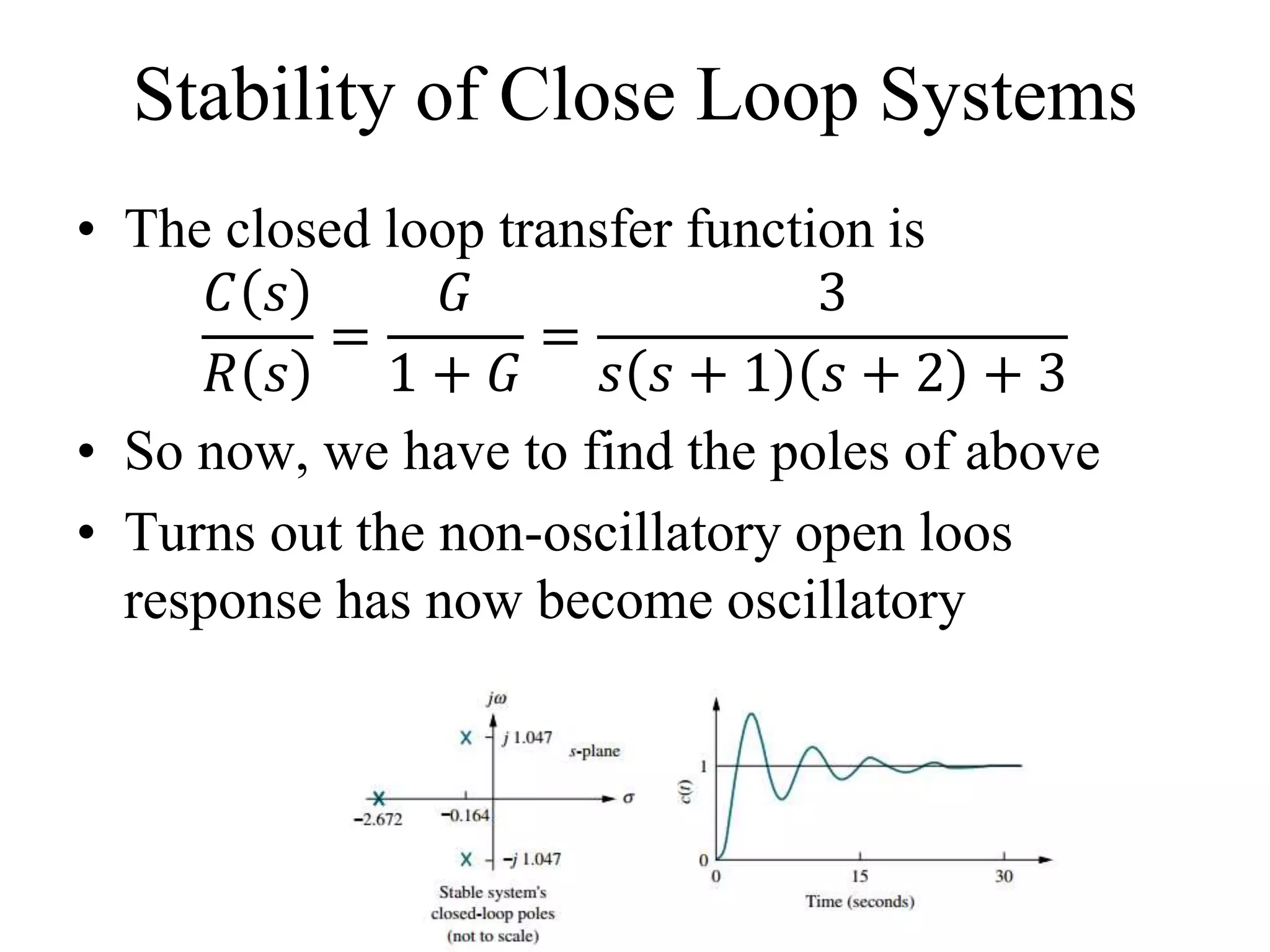

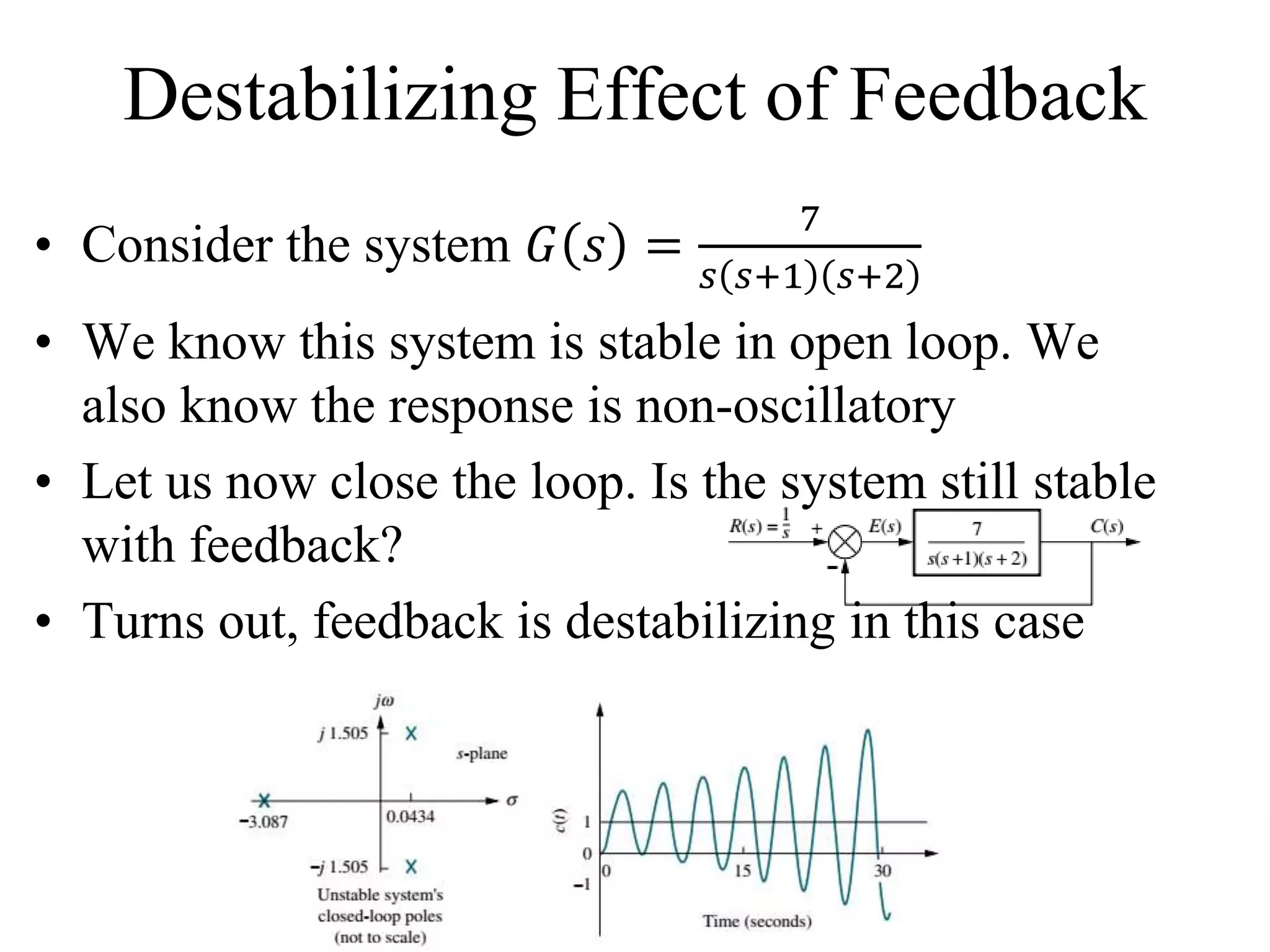

The document covers control engineering topics, specifically focusing on the stability of dynamical systems, including static and dynamic stability, system response, and the importance of poles in determining stability. It discusses feedback influences on system stability, the Routh-Hurwitz criterion for analyzing closed-loop stability, and steady-state errors resulting from system configuration and input types. It emphasizes the relationship between system configuration and steady-state errors, highlighting the role of gain and integrators in achieving desired performance.

![Routh Hurwitz Criterion – Reading

Assignment

• It’s a method that yields stability information

without the need to solve for the closed-loop

system poles.

• Using this method, we can tell how many

closed-loop system poles are in the left half-

plane, in the right half-plane, and on the

imaginary-axis.

• The method is archaic and of practically no

use. I am not going to waste a whole lecture on

this, and so this is part of your reading

assignment. Watch these lectures [1, 2, 3]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/me314-week08-stabilityandsserrors-171018123351/75/Me314-week08-stability-and-steady-state-errors-10-2048.jpg)

![Assignment 5a

• Watch these lectures [1, 2, 3] on Routh

Hurwitz method by Brian Douglas.

• Solve the following problems from Nise Ch 6

• Questions 42, 55, 57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/me314-week08-stabilityandsserrors-171018123351/75/Me314-week08-stability-and-steady-state-errors-11-2048.jpg)