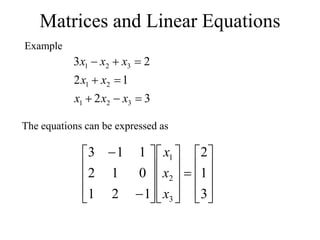

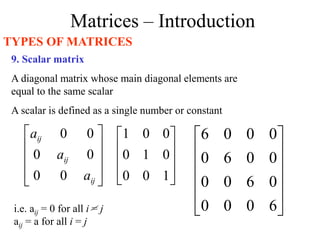

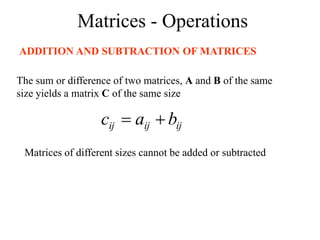

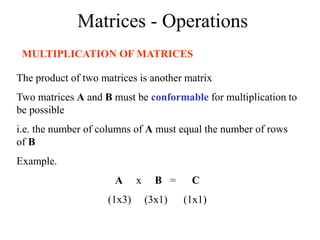

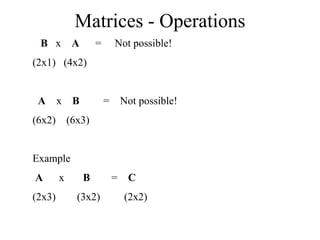

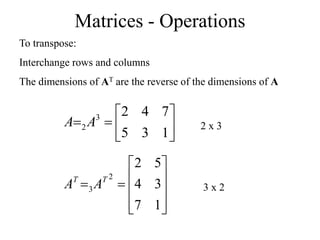

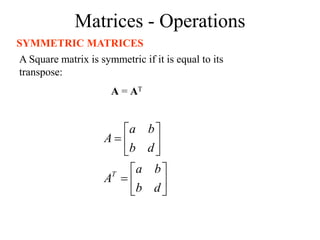

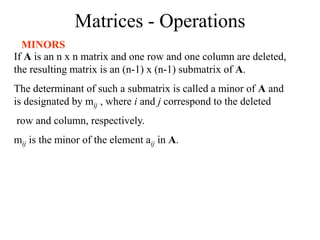

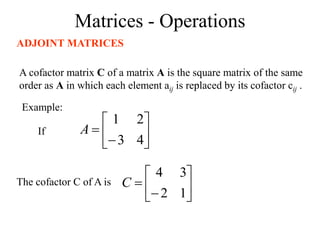

The document provides an overview of matrix algebra, covering key concepts such as definitions, types of matrices, operations including addition, subtraction, scalar multiplication, and multiplication of matrices. It also discusses properties of matrices, determinants, and concepts like symmetry and transposition. This foundational information is essential for understanding systems of linear equations and mathematical treatments involving matrices.

![Matrices - Operations

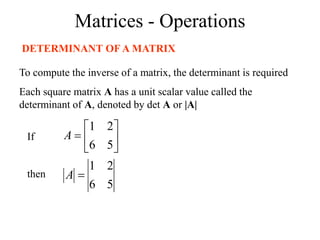

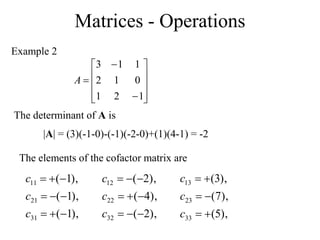

If A = [A] is a single element (1x1), then the determinant is

defined as the value of the element

Then |A| =det A = a11

If A is (n x n), its determinant may be defined in terms of order

(n-1) or less.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-matrices-210206152516/85/Matrices-Basics-Determinant-Inverse-EigenValues-Linear-Equations-RANK-30-320.jpg)

![2

2

)

1

)(

10

(

)

1

)(

10

)(

1

(

]

10

11

)[

1

(

]

8

)

2

)(

9

)[(

1

(

2

4

2

2

9

4

0

0

1

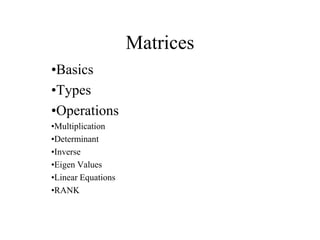

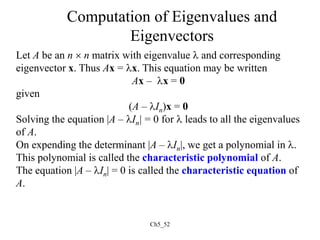

We now solving the characteristic equation of A:

The eigenvalues of A are 10 and 1.

The corresponding eigenvectors are found by using three values

of in the equation (A – I3)x = 0.

10

,

1

0

)

1

)(

10

( 2

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-matrices-210206152516/85/Matrices-Basics-Determinant-Inverse-EigenValues-Linear-Equations-RANK-57-320.jpg)