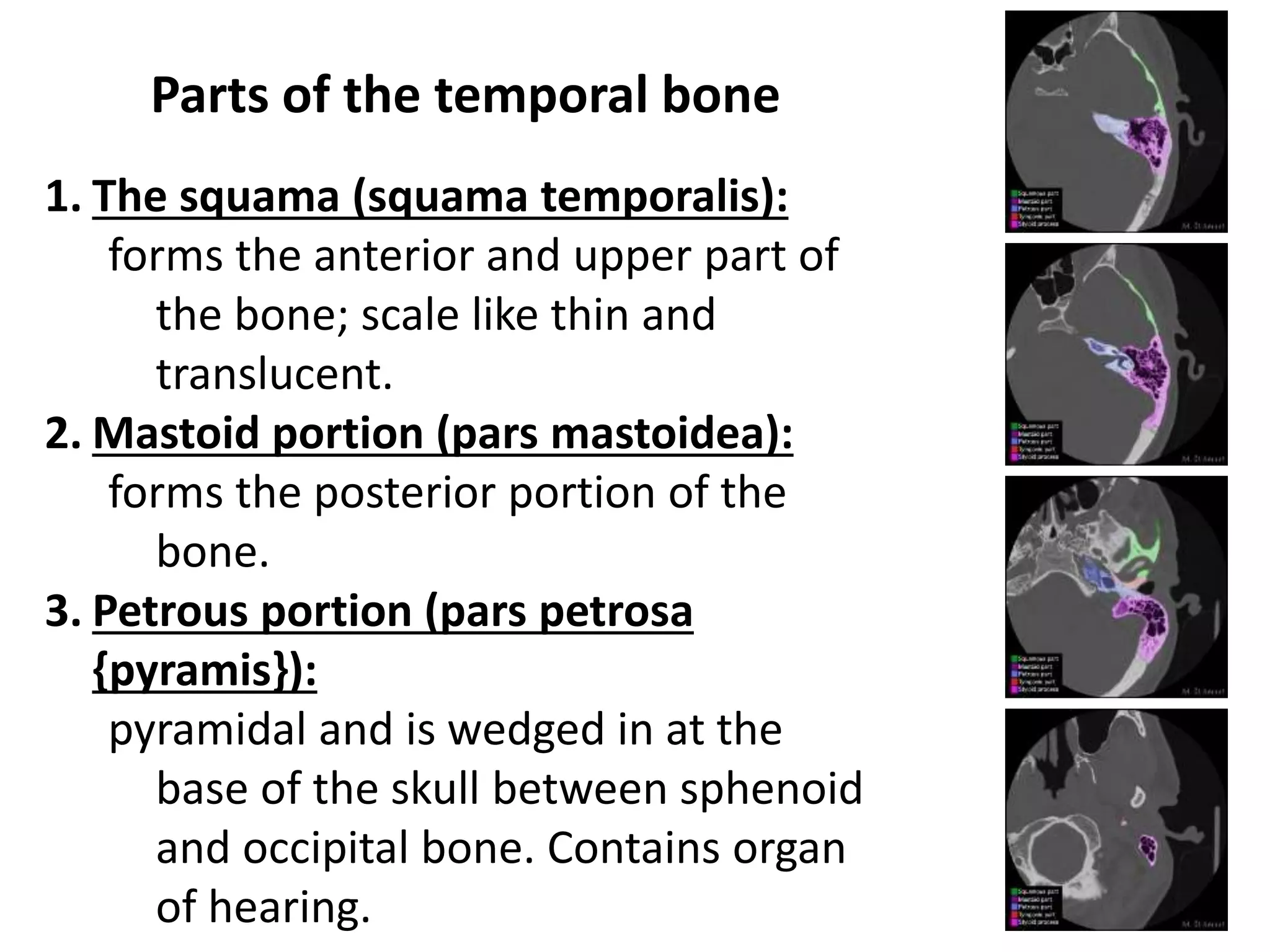

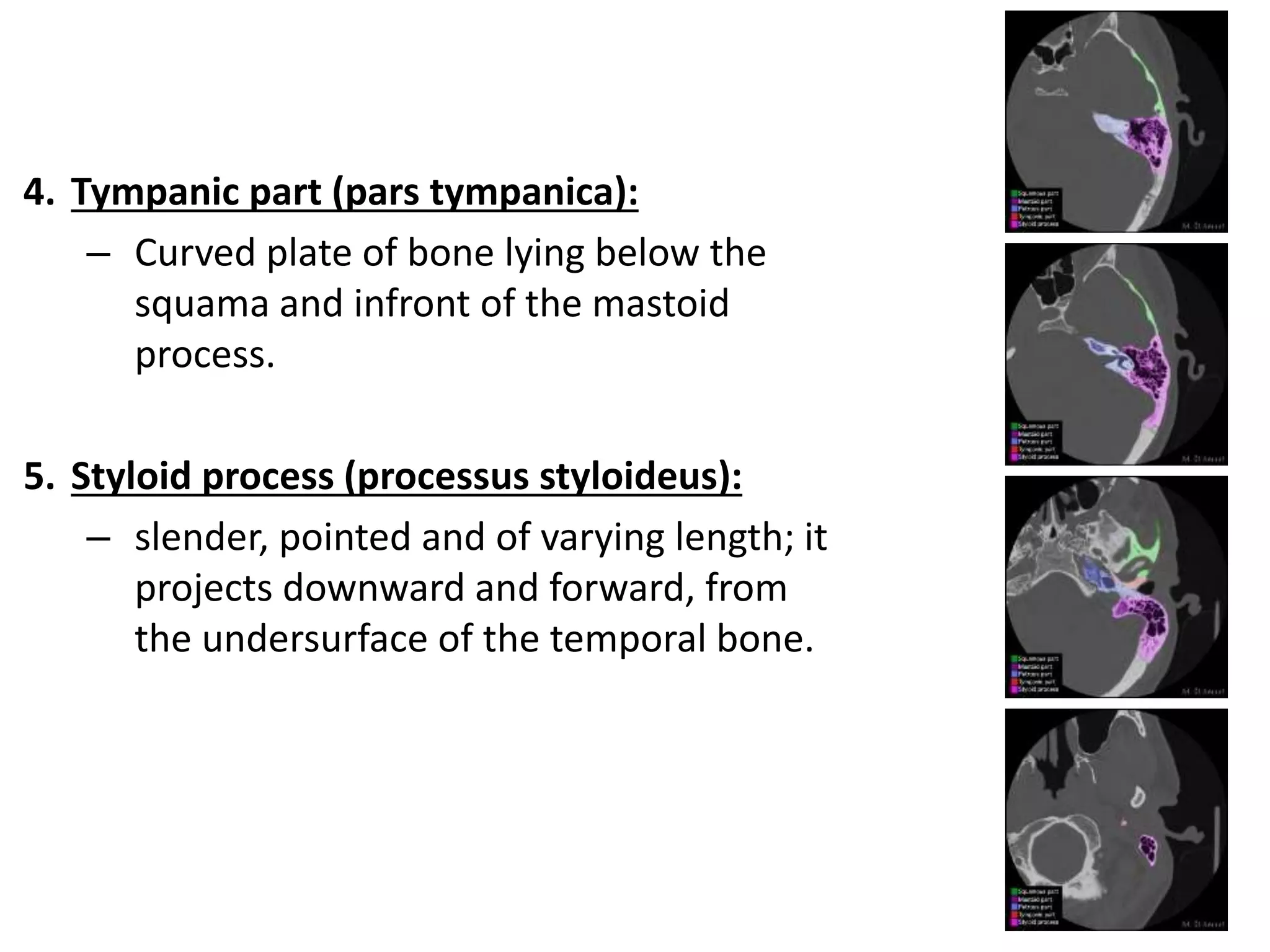

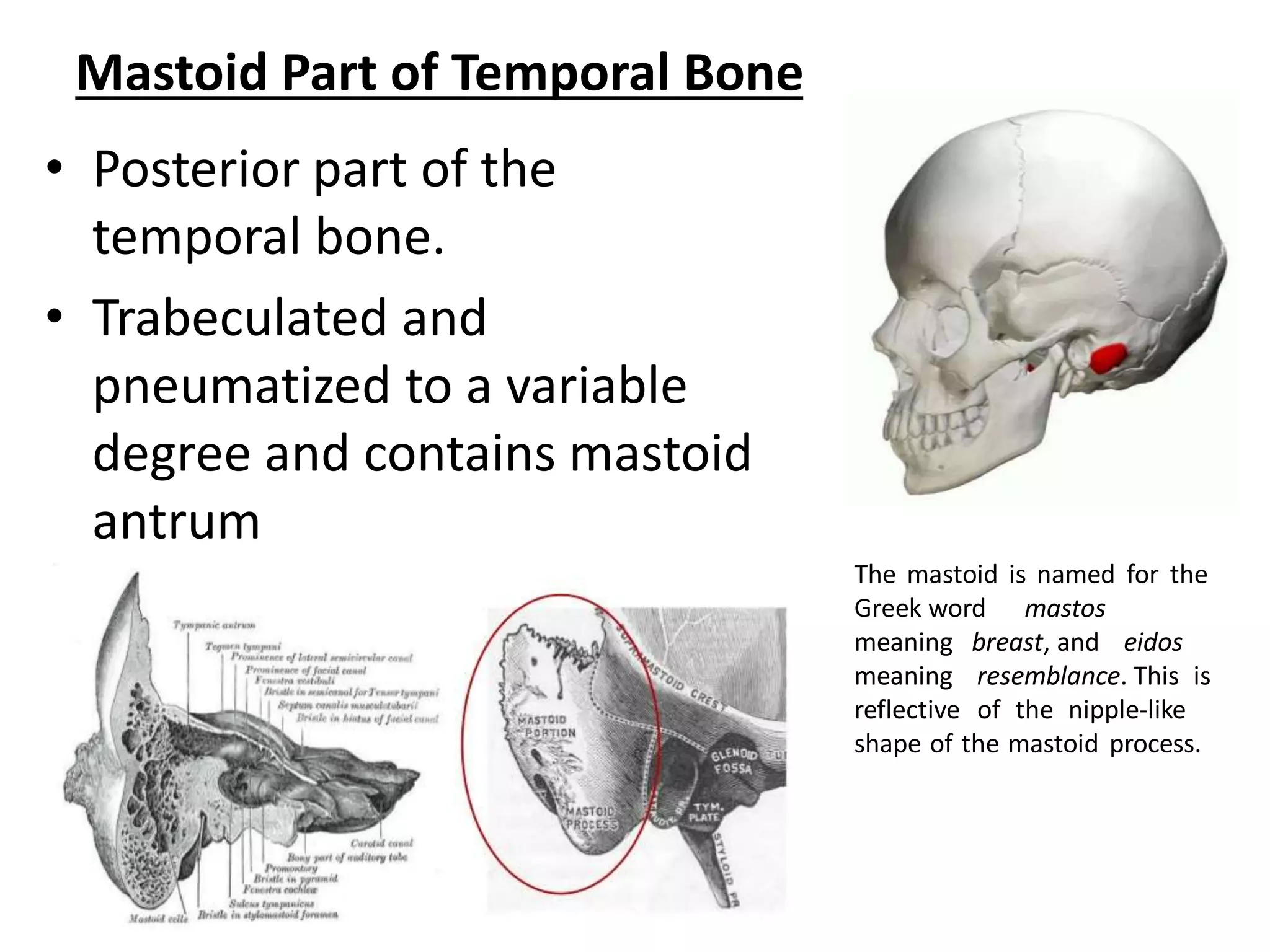

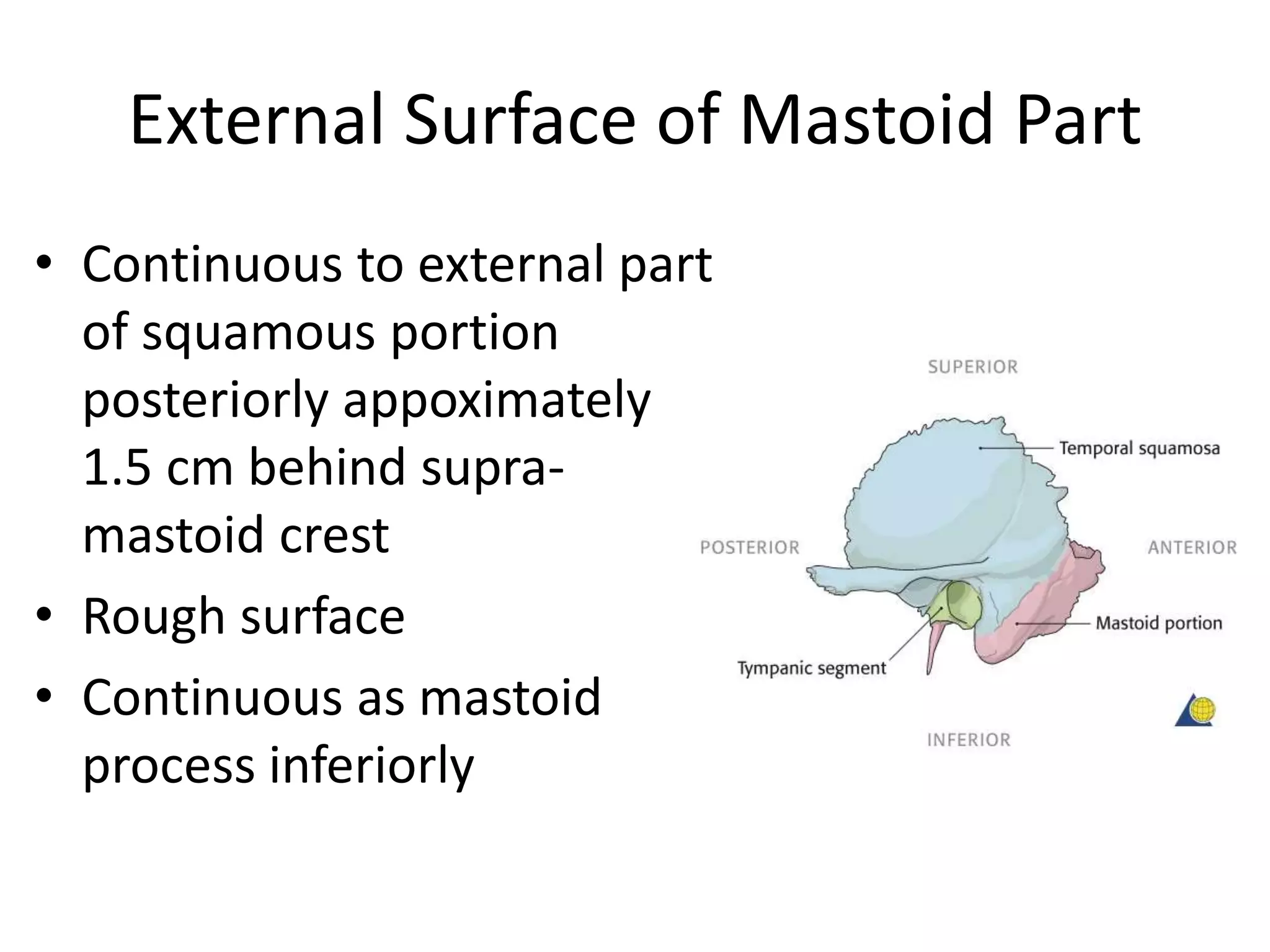

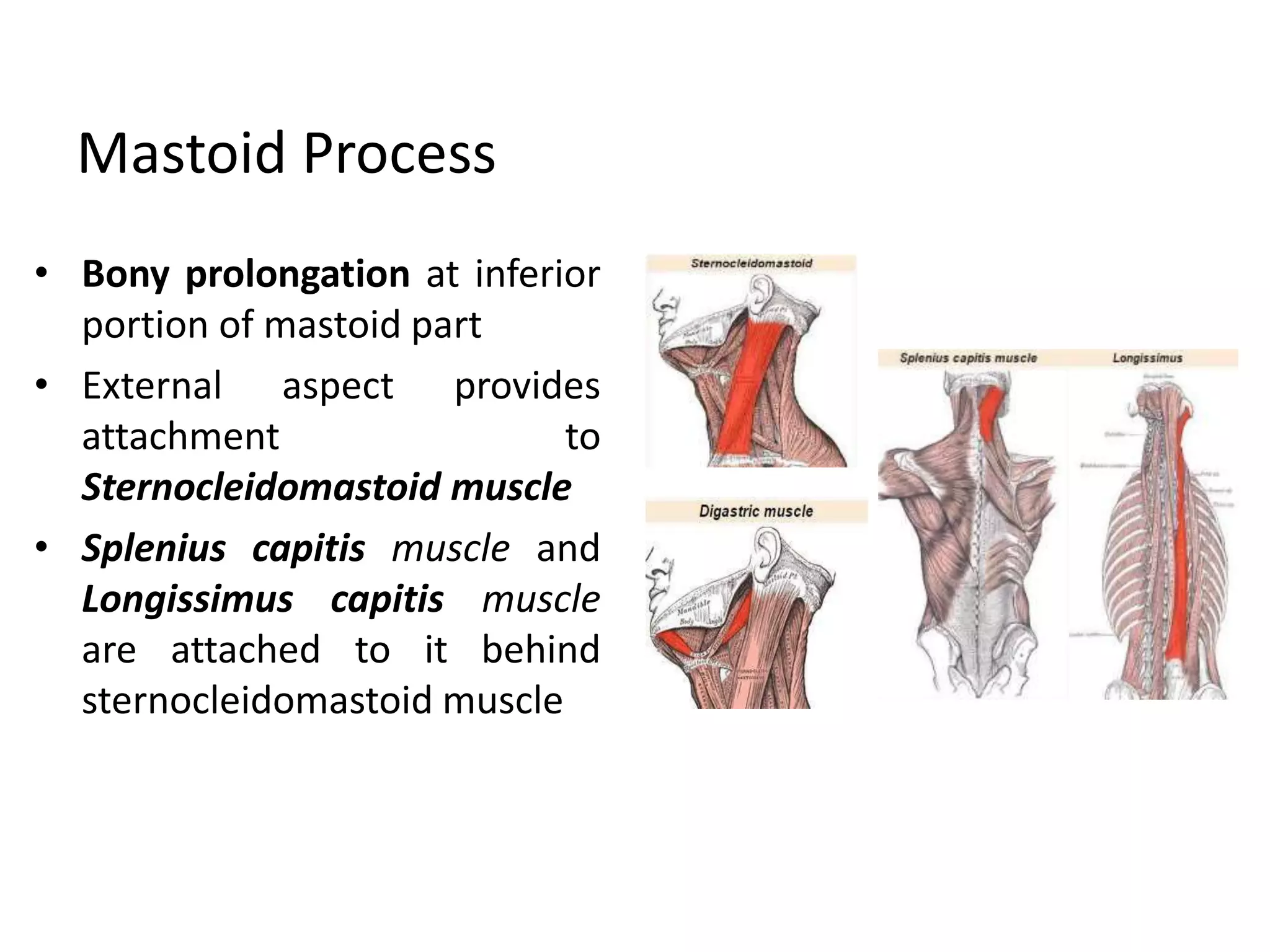

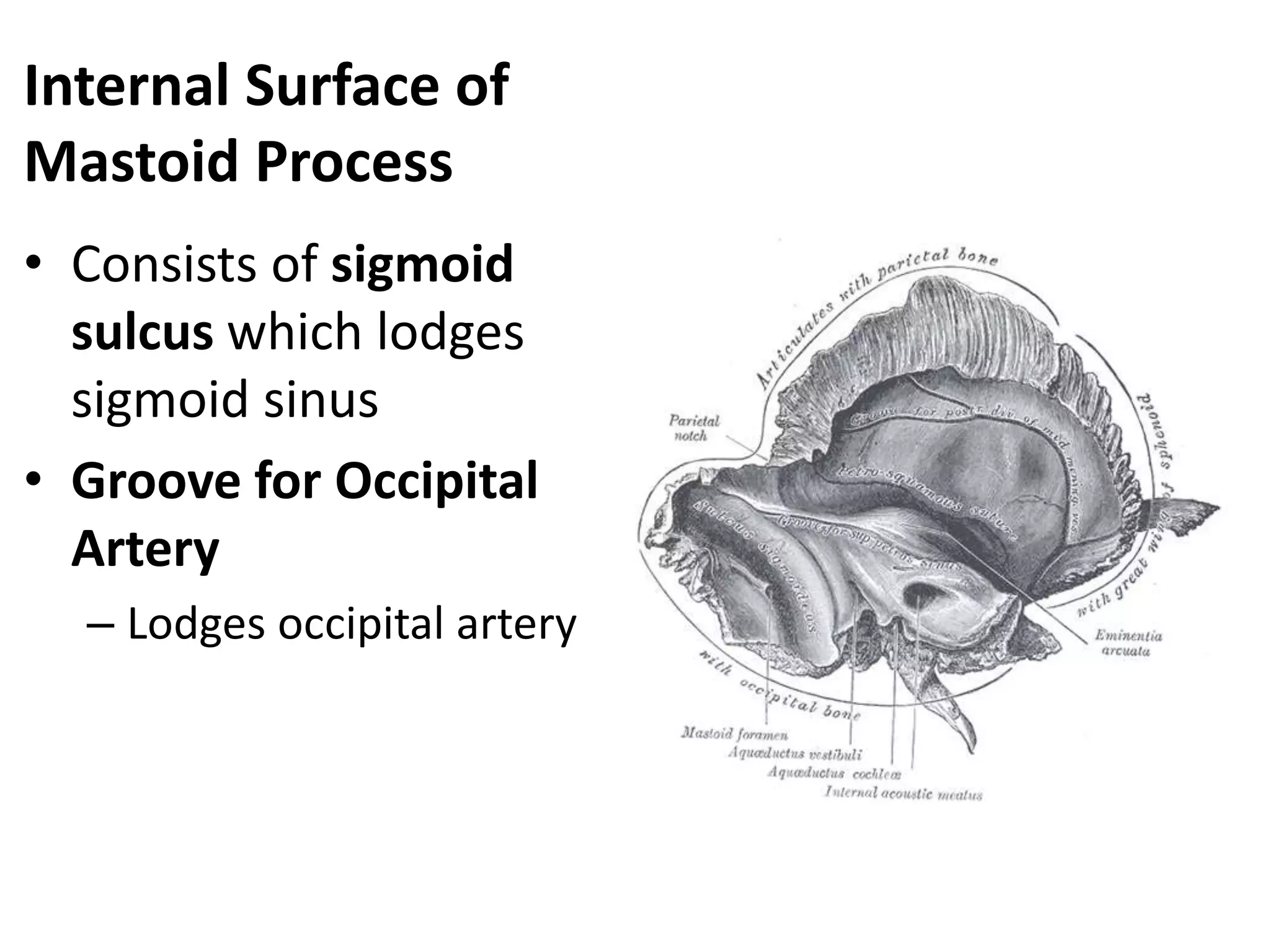

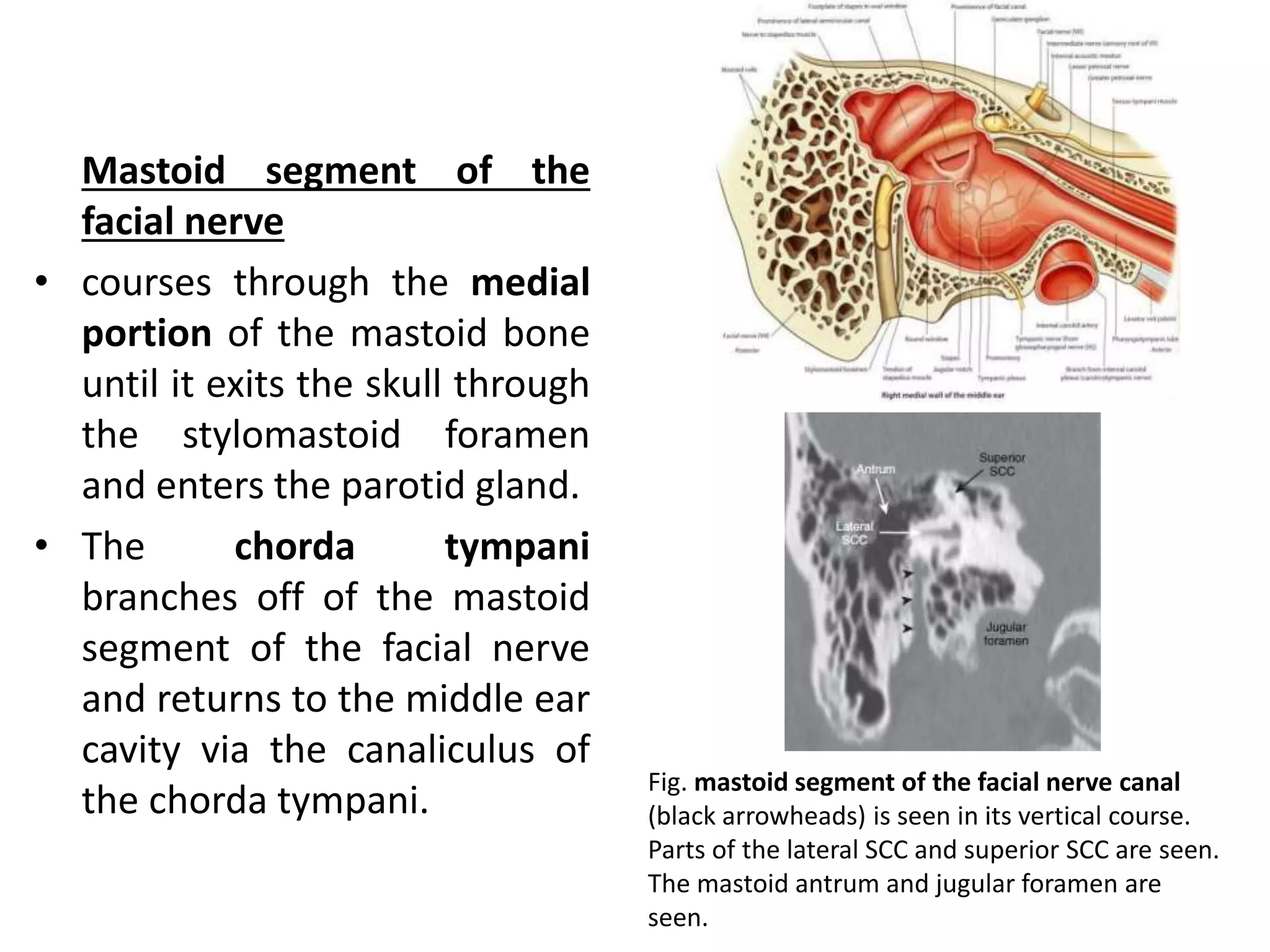

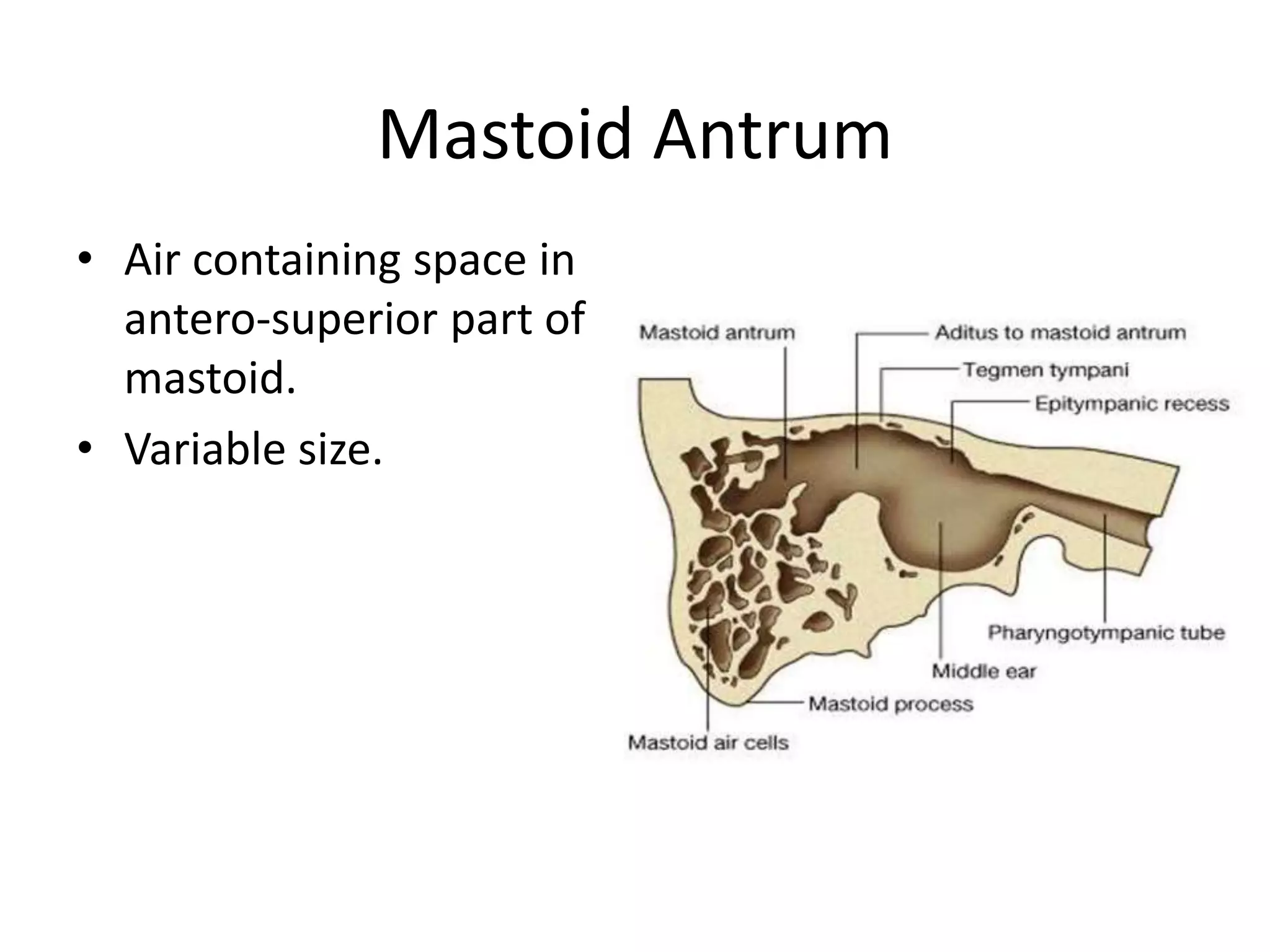

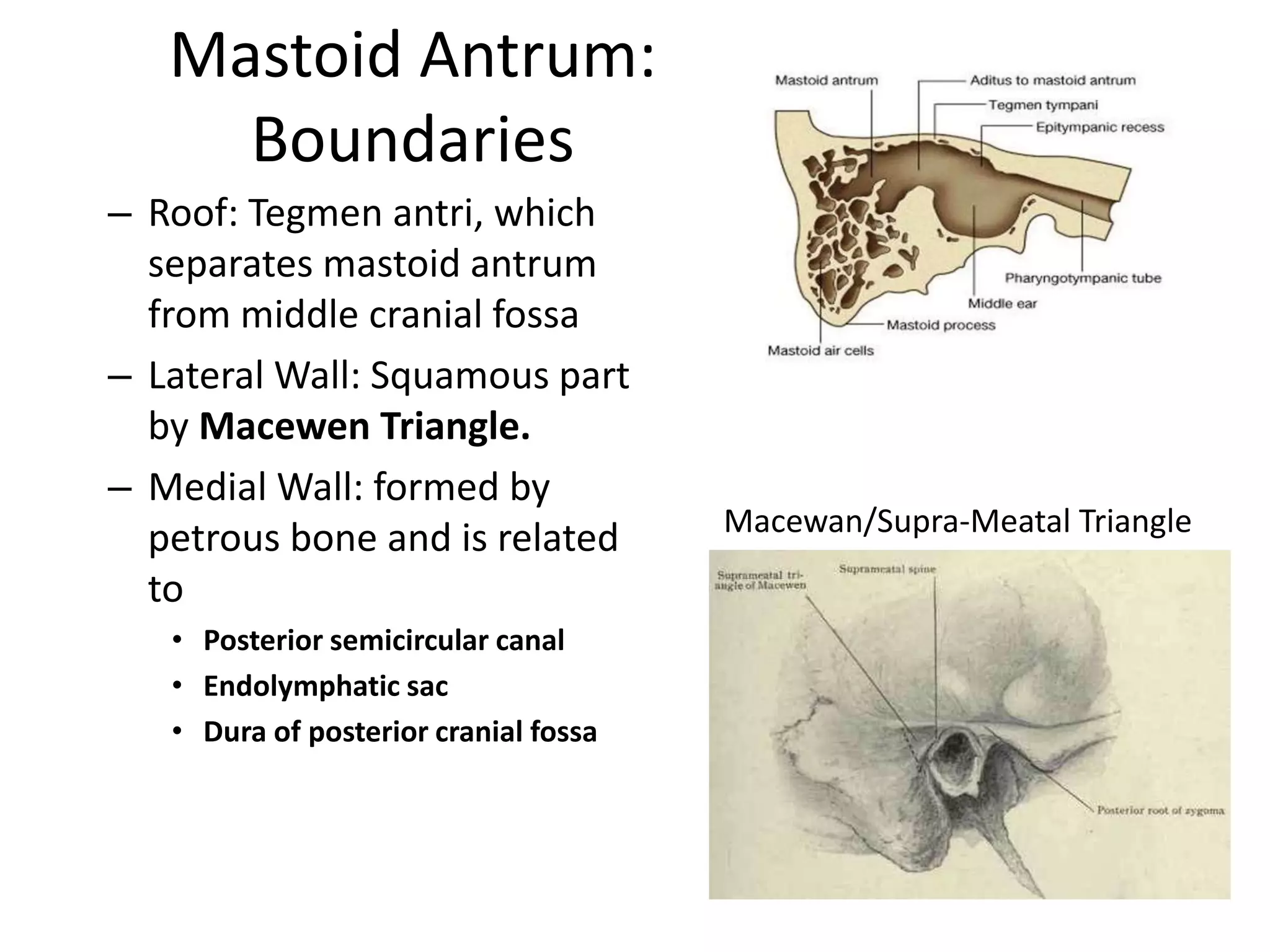

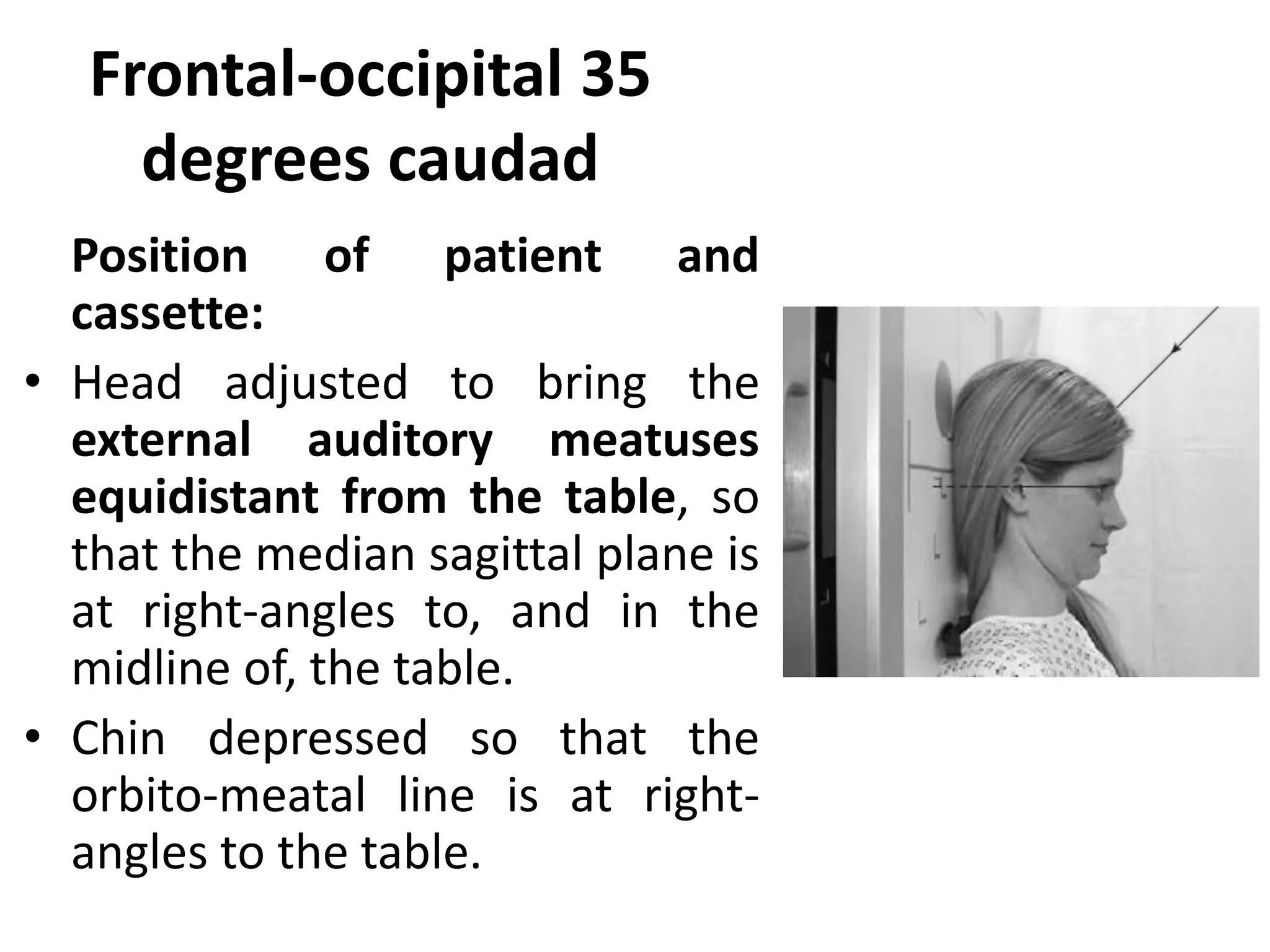

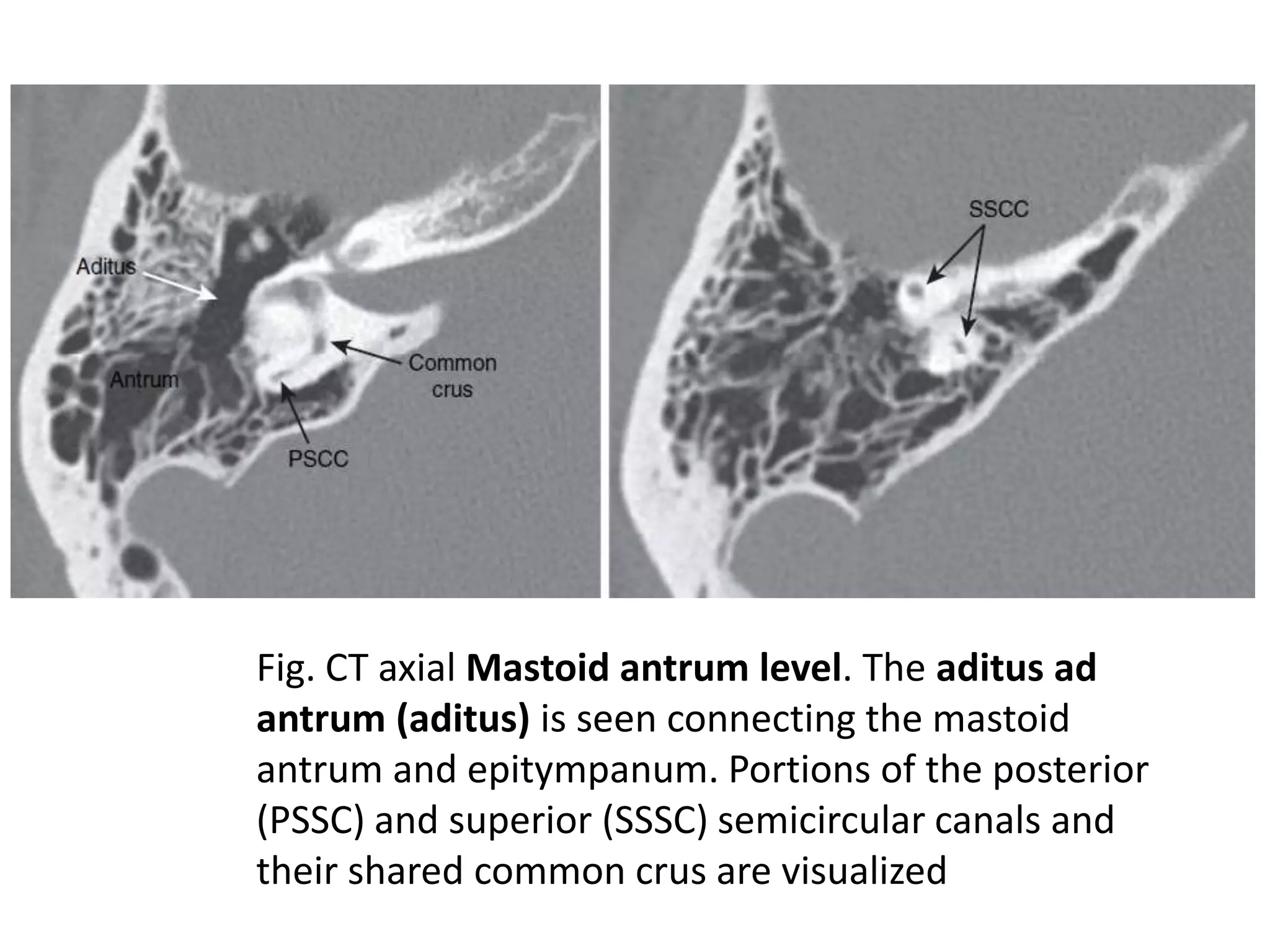

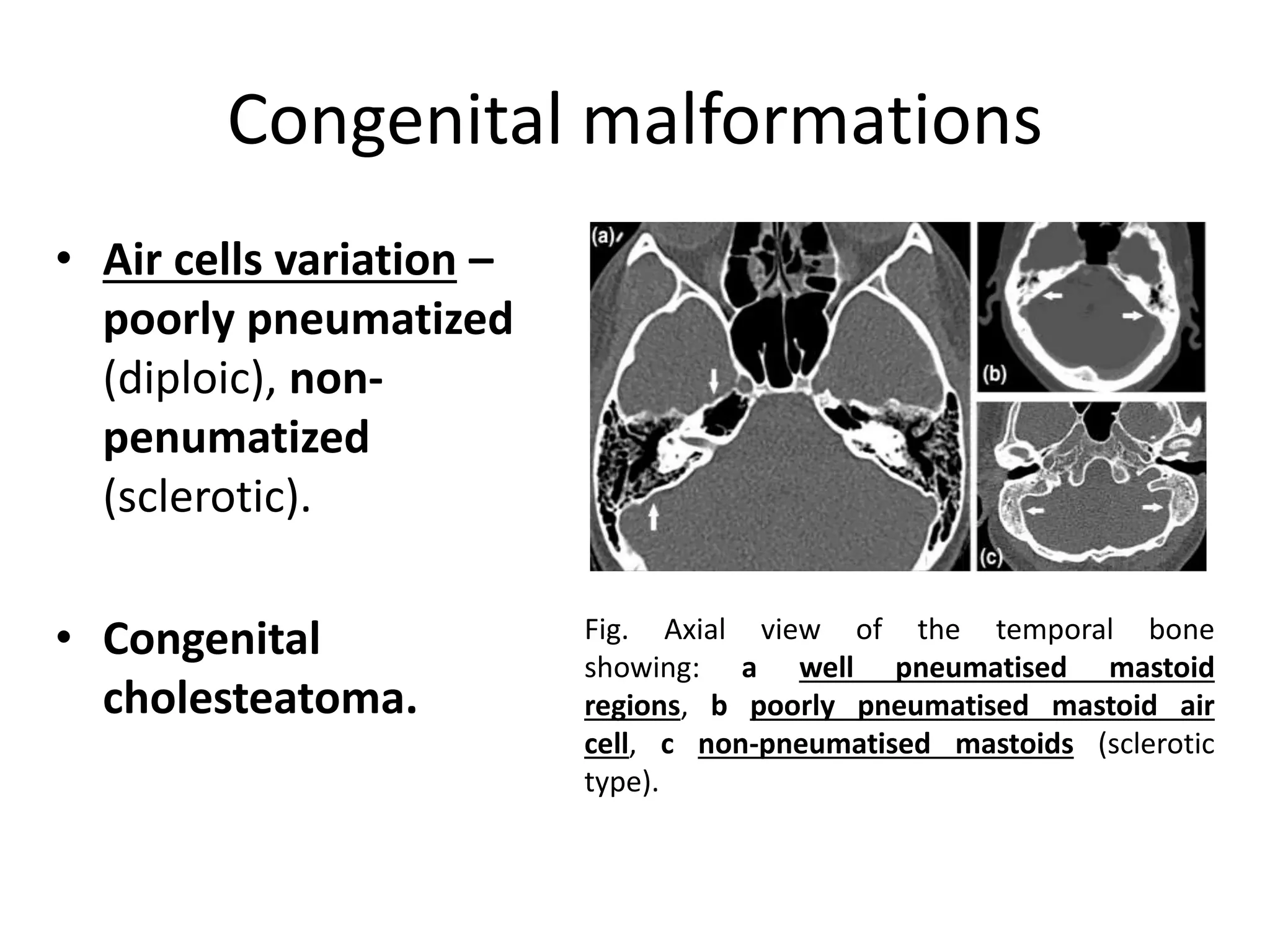

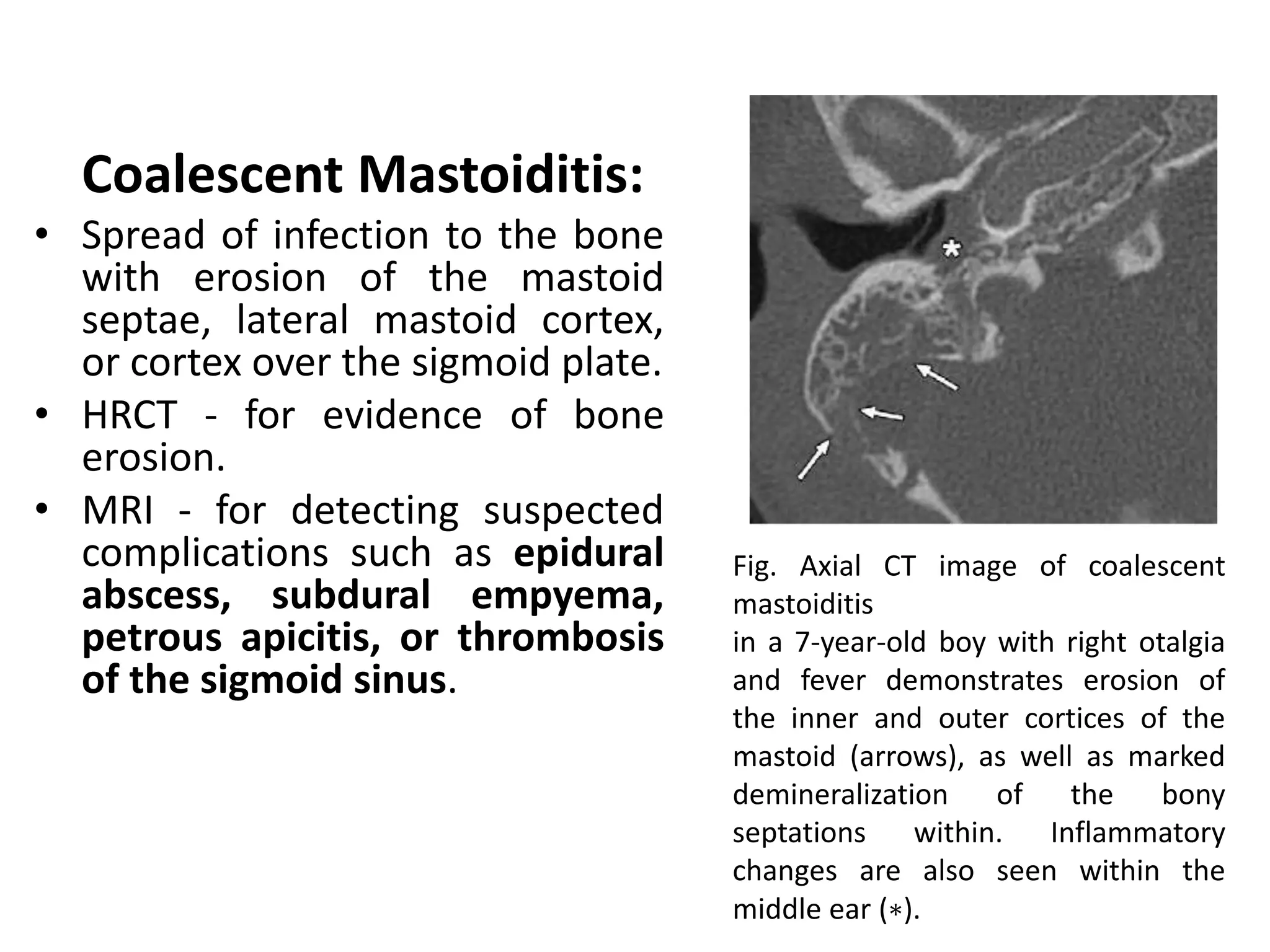

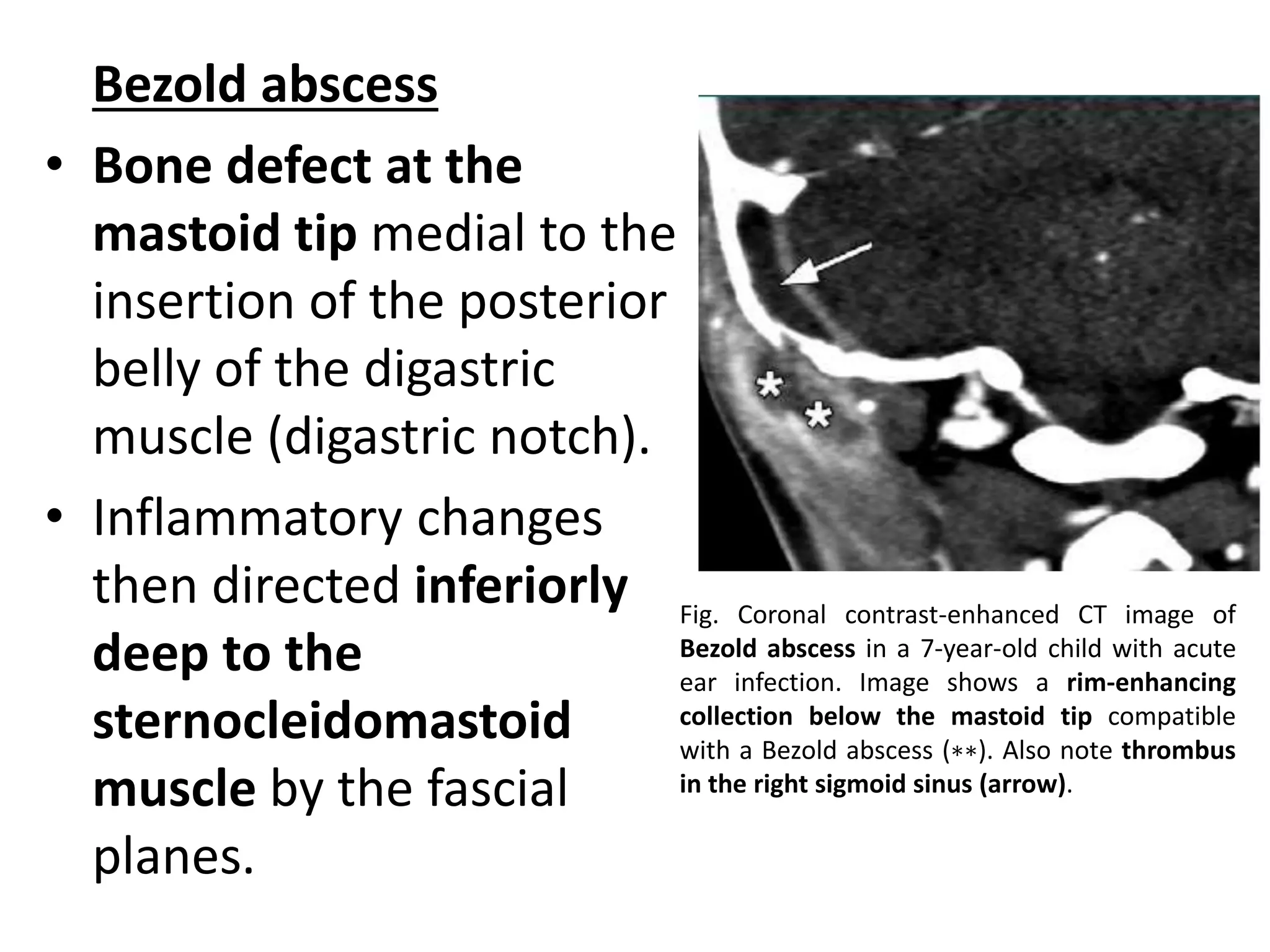

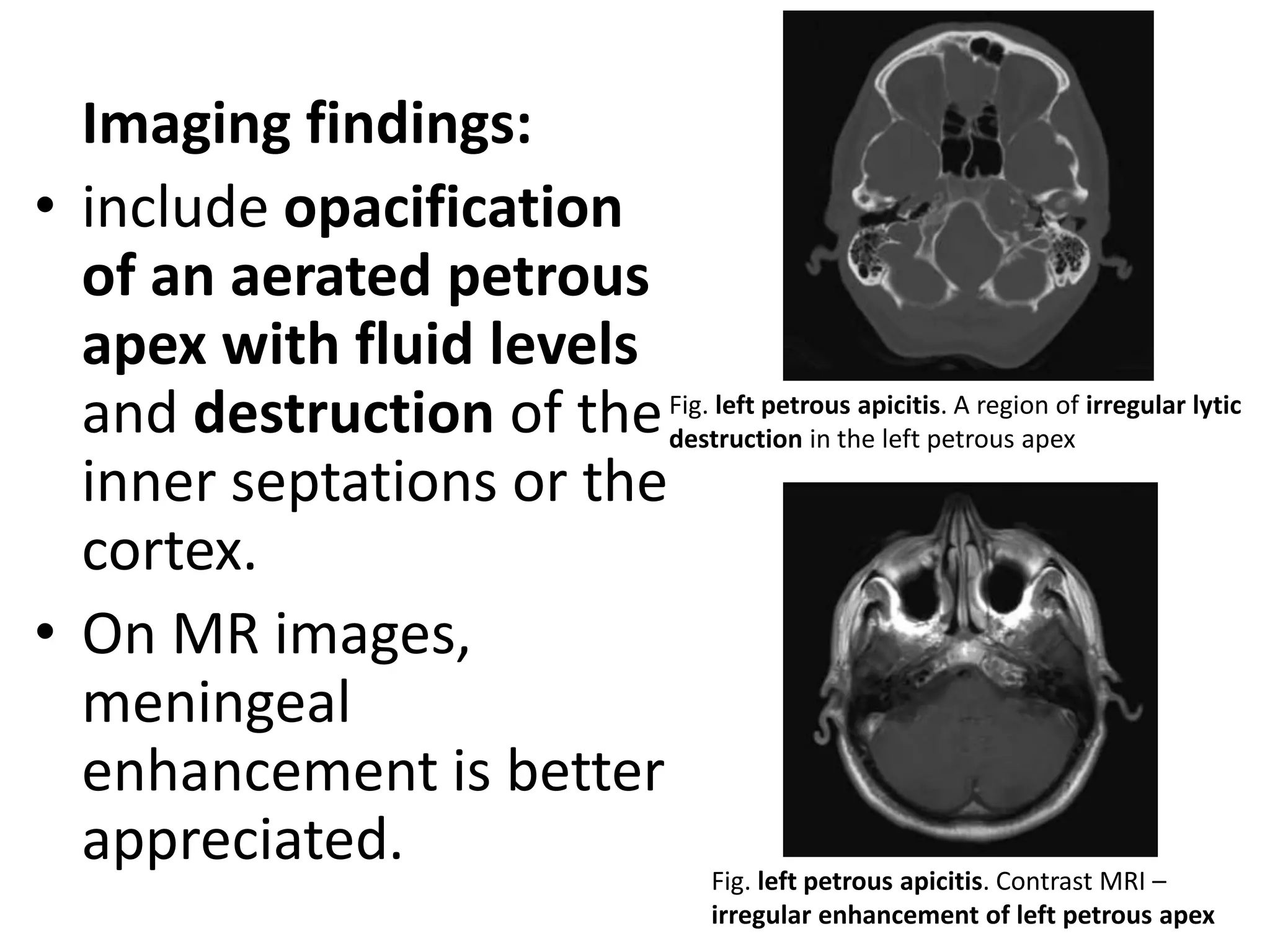

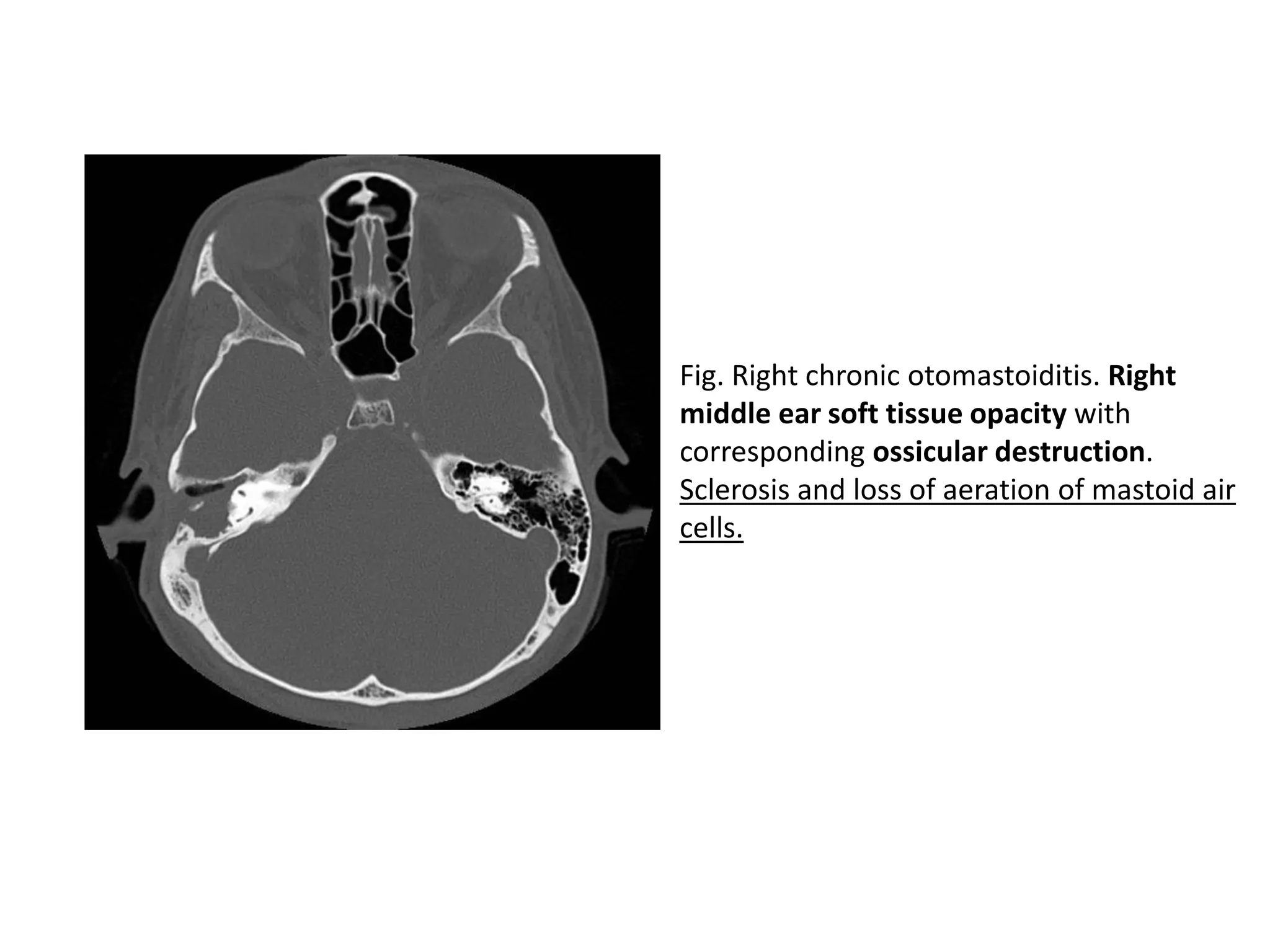

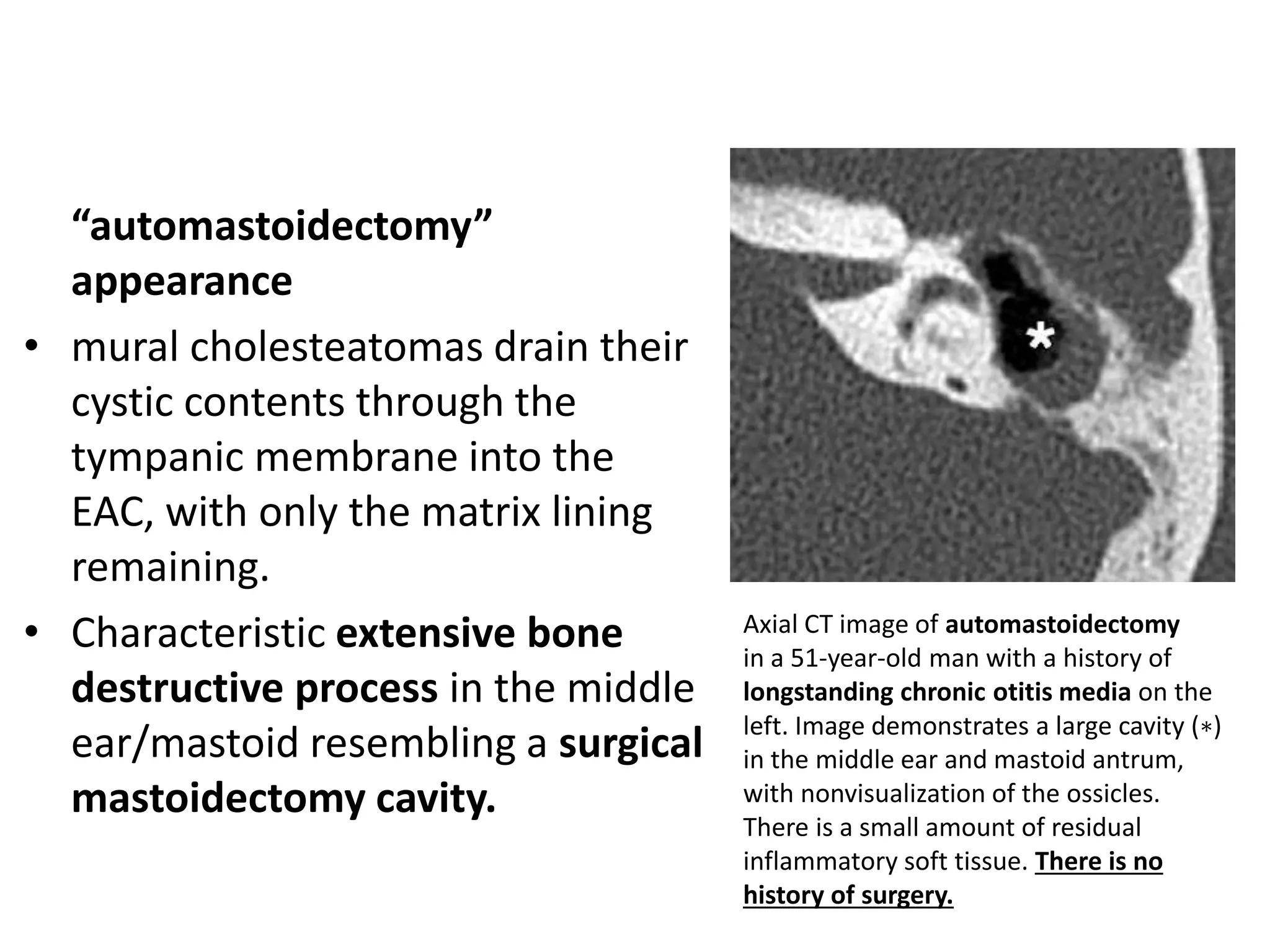

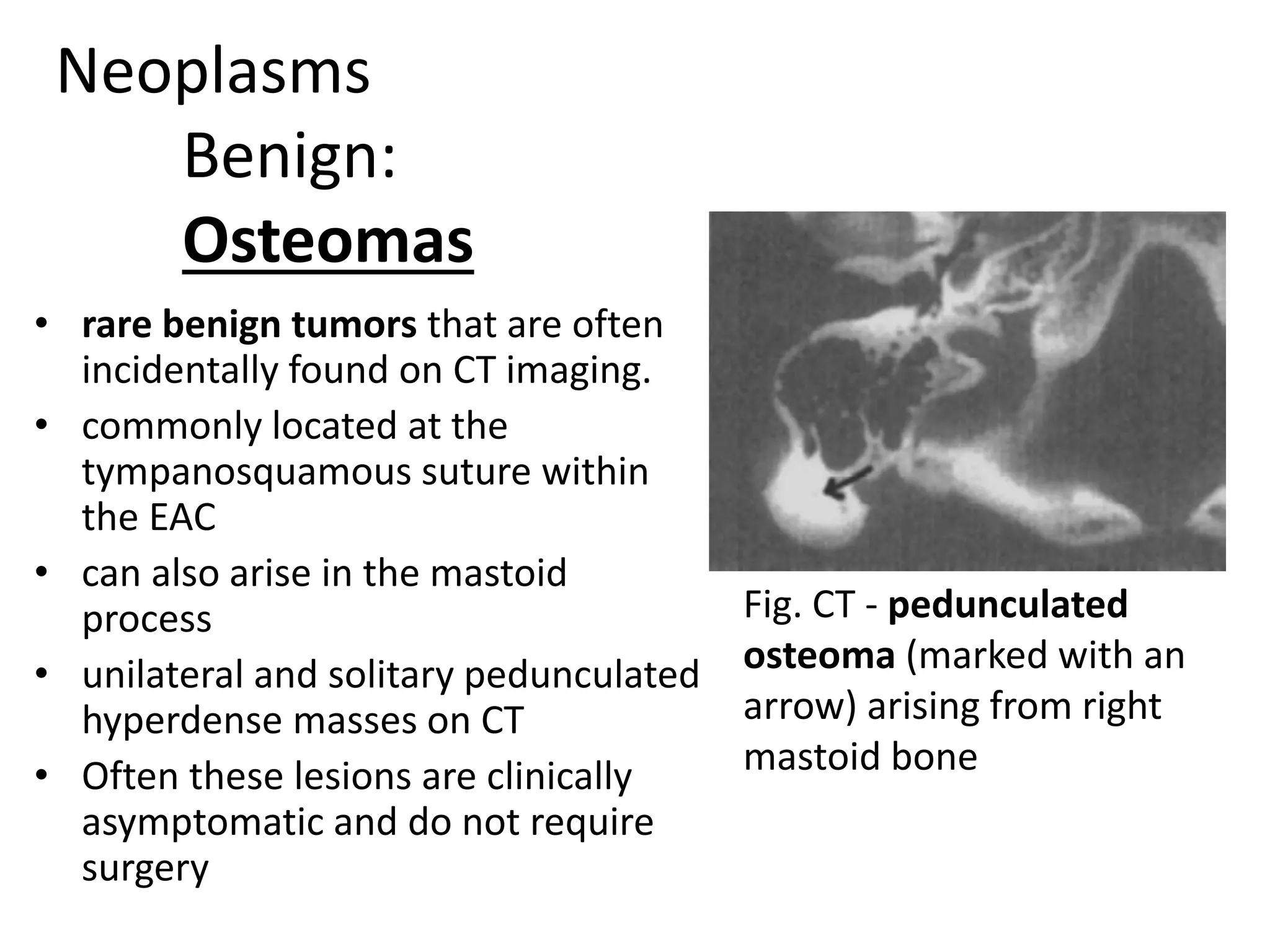

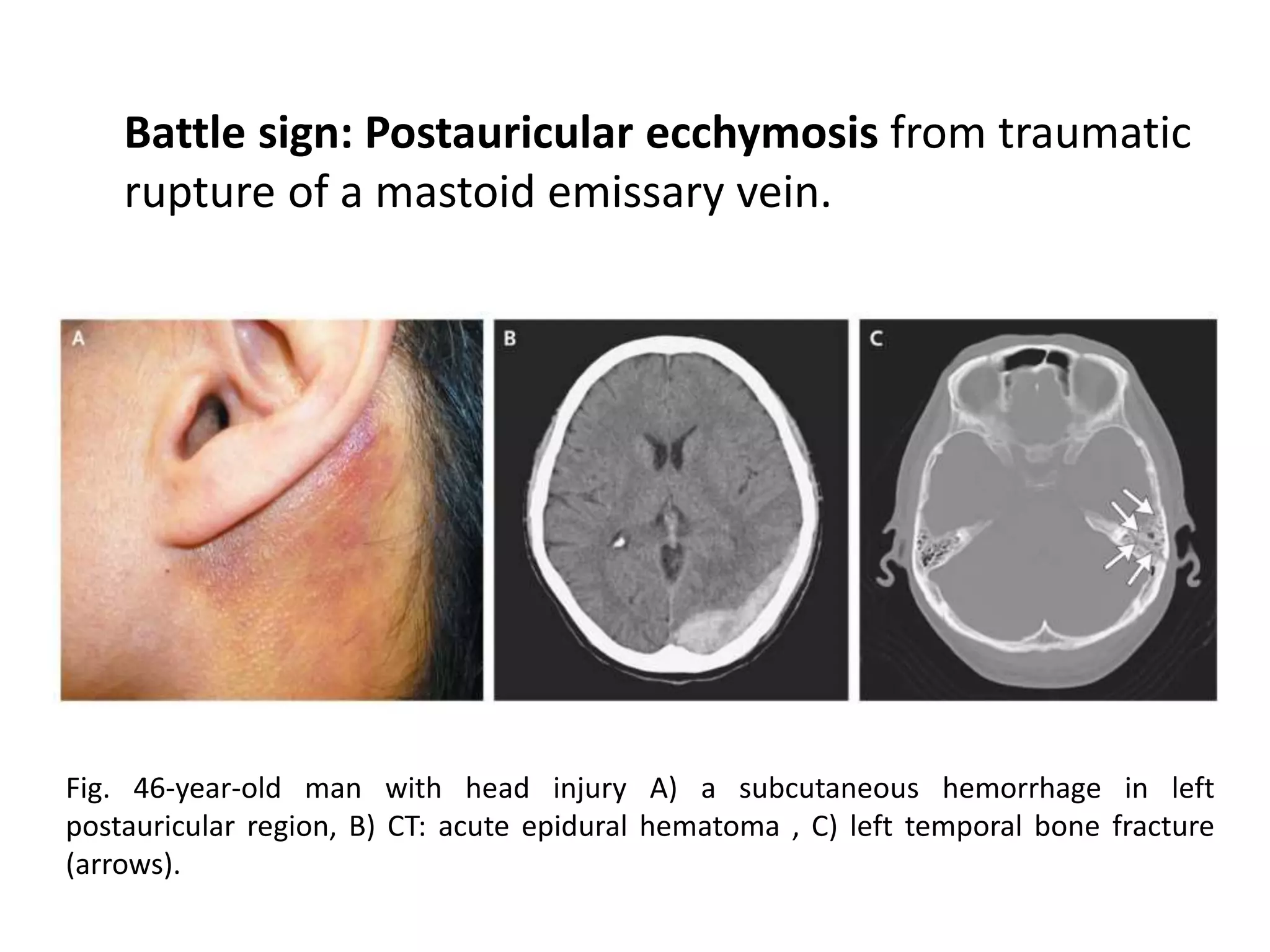

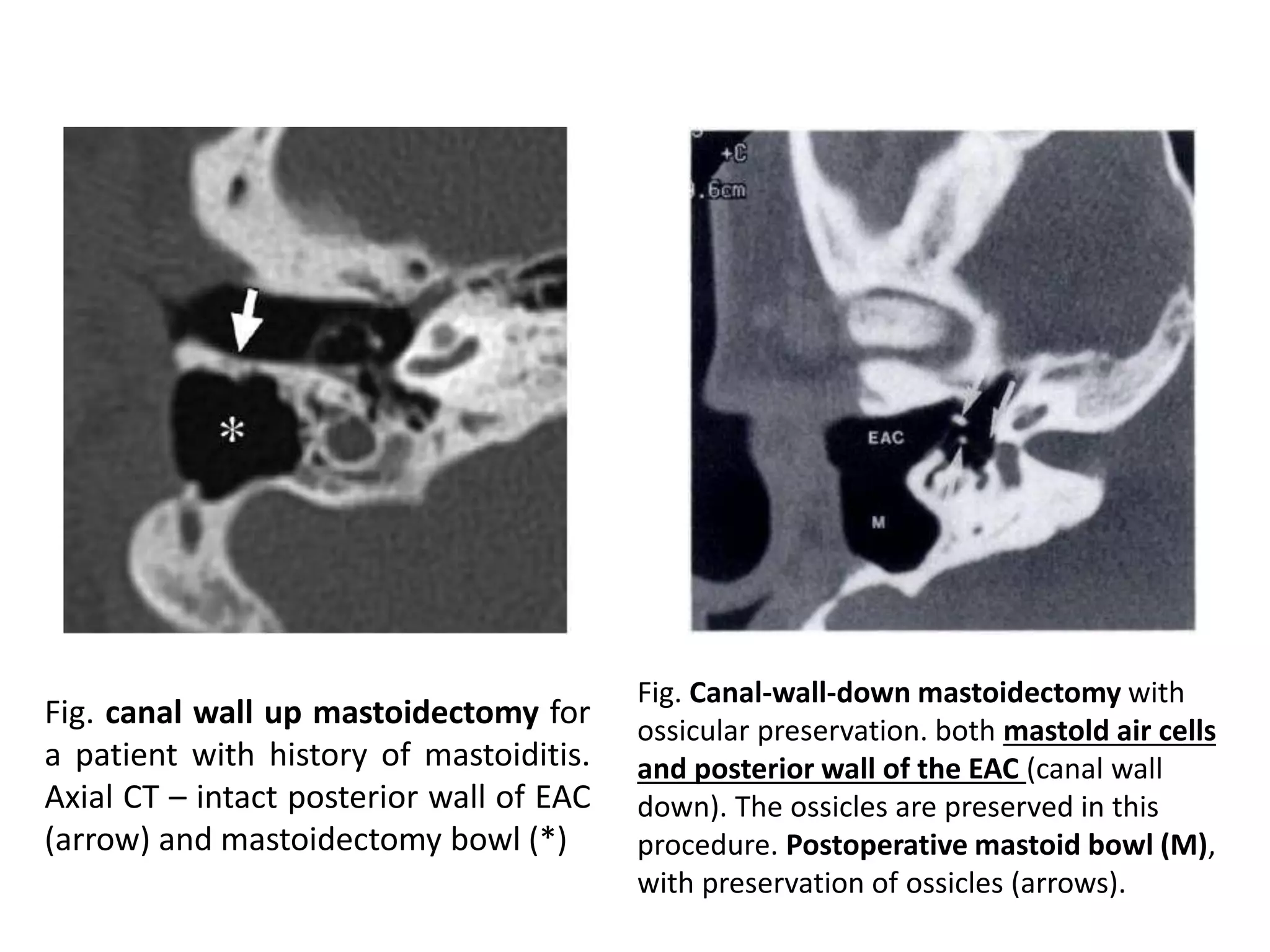

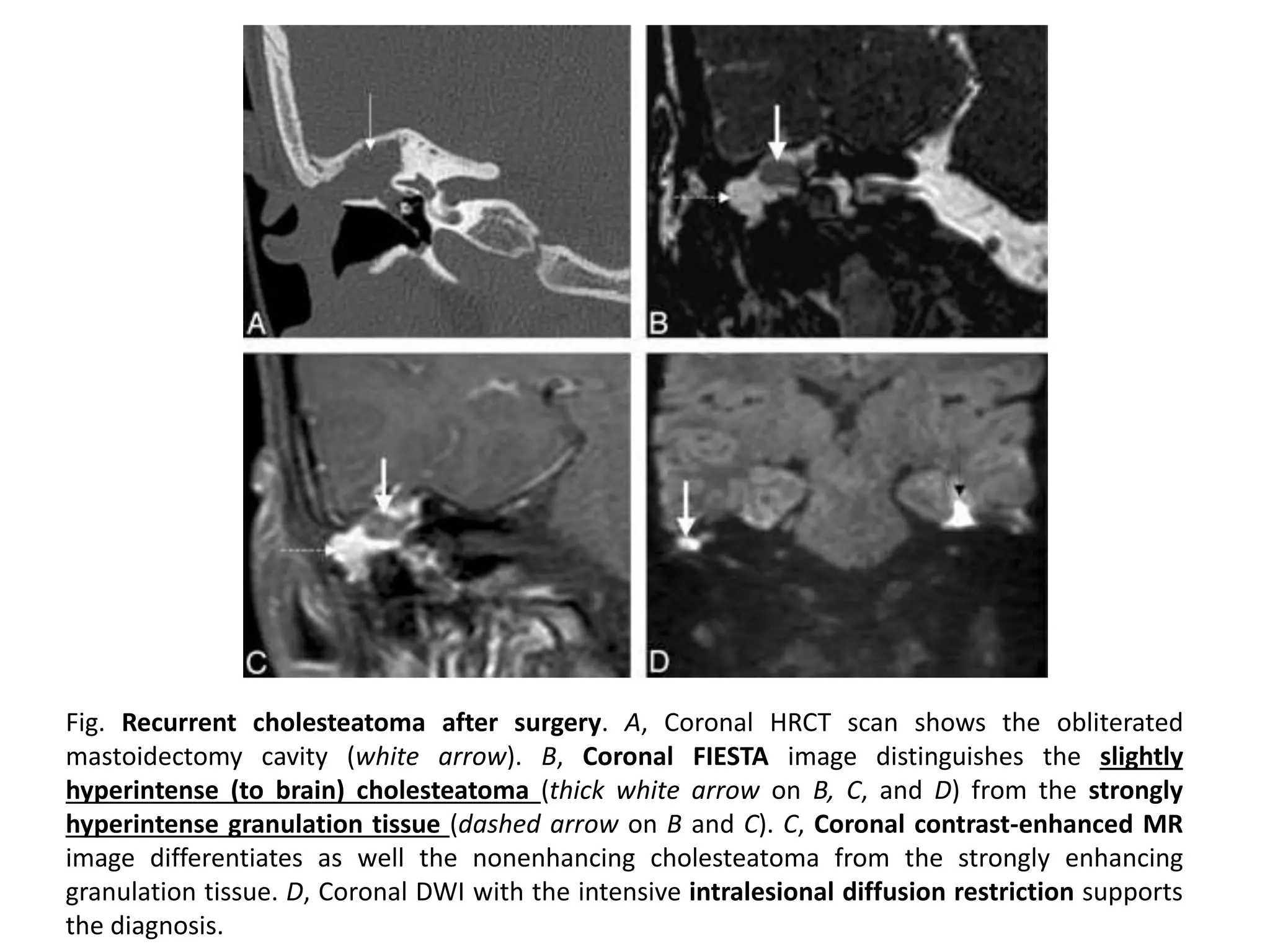

The document discusses imaging of diseases of the mastoid. It begins with the normal anatomy of the mastoid portion of the temporal bone, including its external and internal surfaces. Common pathologies seen in mastoid imaging are then described, such as congenital malformations, infections like acute otomastoiditis, neoplasms, fractures, and post-surgical changes. Relevant imaging modalities like CT and MRI are discussed. CT is highlighted as the best method for evaluating bone and air space anatomy due to its high spatial resolution.