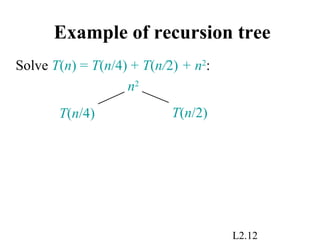

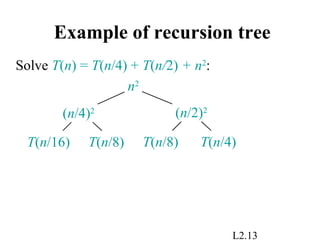

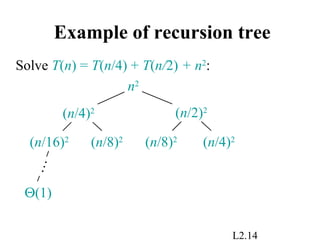

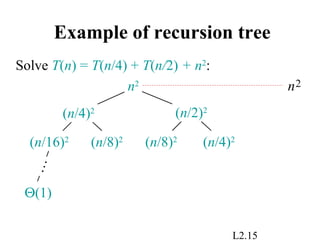

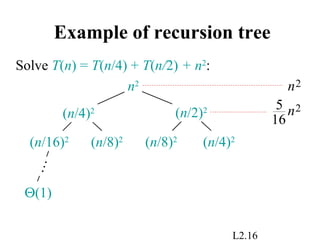

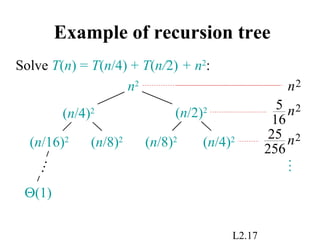

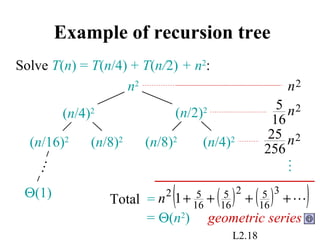

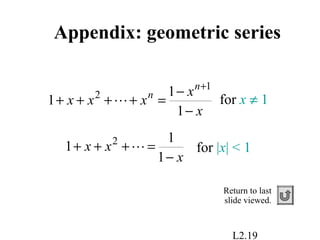

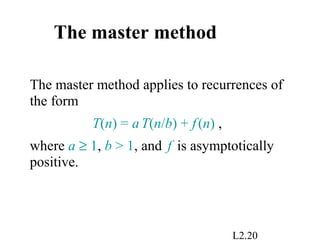

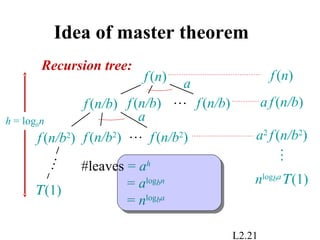

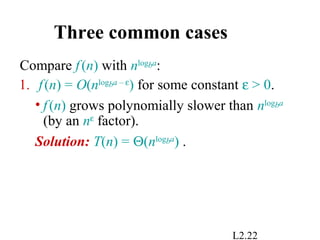

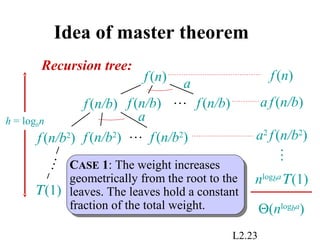

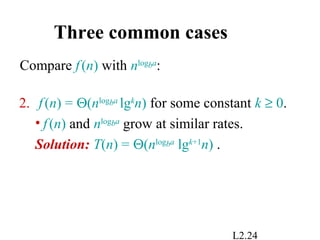

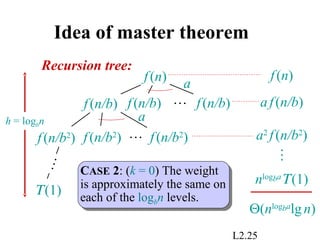

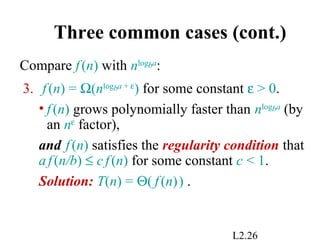

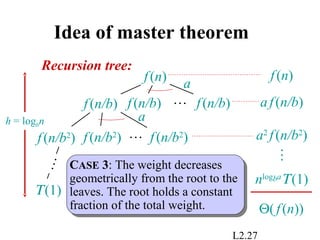

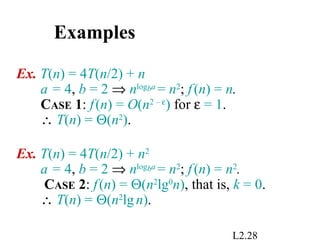

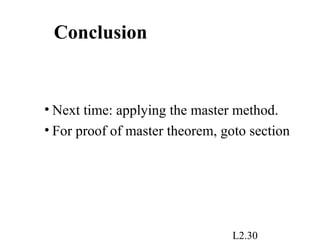

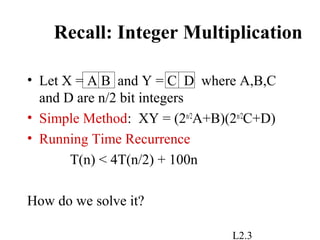

This document discusses techniques for solving recurrence relations that arise in the analysis of algorithms. It introduces the substitution method, where an educated guess for the solution is verified by induction. The recursion tree method provides intuition by modeling the recursive execution as a tree. Key examples are worked through. The master method is presented as a powerful tool for solving recurrences of the form T(n) = aT(n/b) + f(n), by comparing the growth rates of f(n) and nlogba.

![L2.4

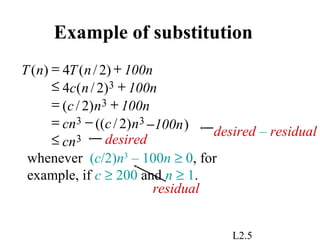

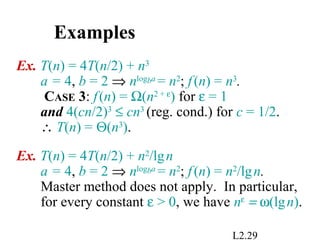

Substitution method

1. Guess the form of the solution.

2. Verify by induction.

3. Solve for constants.

The most general method:

Example: T(n) = 4T(n/2) + 100n

• [Assume that T(1) = Θ(1).]

• Guess O(n3

) . (Prove O and Ω separately.)

• Assume that T(k) ≤ ck3

for k < n .

• Prove T(n) ≤ cn3

by induction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2-160831201559/85/L2-4-320.jpg)