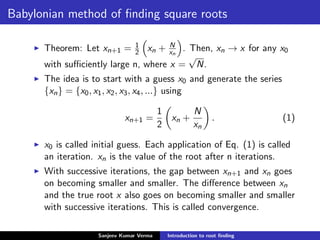

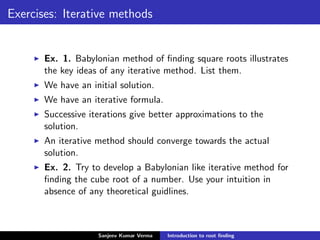

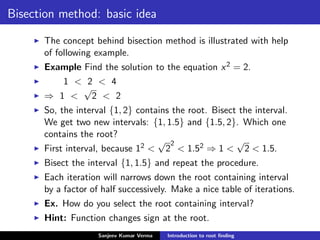

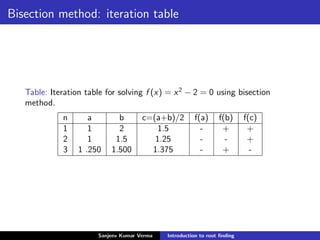

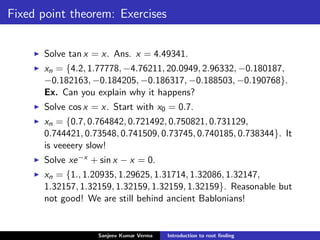

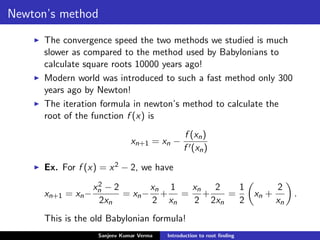

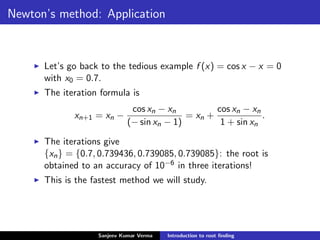

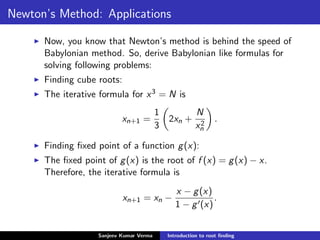

The document provides an overview of root-finding methods, including the bisection method, fixed-point method, and the Babylonian method for finding square roots. It discusses the iterative processes involved in these methods, their convergence rates, and includes exercises for better understanding. The bisection method is highlighted as fundamental despite its slower convergence, while fixed-point methods are analyzed for their conditions of existence and uniqueness.

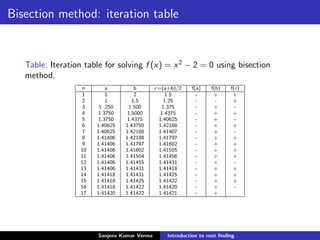

![Bisection method: Estimate of convergence

Bisection method converge very slowly. How do we estimate the

number of iterations needed to solve an equation correct upto (say)

3, 4 or 5 places of decimal?

Suppose, we have to solve f (x) = 0 and the true solution is p. Let

[a, b] is the interval which contains the root.

Bisection method successively bisects the interval [a, b] into smaller

intervals [a1, b1], [a2, b2], [a3, b3] ... [an, bn] where

(bn − an) =

1

2n

(b − a). (2)

Bisection method successively approximates the root by

pn =

1

2

(an + bn) (3)

so that the sequence {pn} approaches p in the large n limit with

|pn − p| ≤

b − a

2n

. (4)

Actual error can be smaller than the above estimate.

Sanjeev Kumar Verma Introduction to root finding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontorootfinding-201120180953/85/Introduction-to-root-finding-10-320.jpg)

![Fixed point theorem

(i) Consider a continuous function g(x) defined on the

interval [a, b]. If g(x) ∈ [a, b] ∀ x ∈ [a, b], ∃ a fixed point

p ∈ [a, b] defined as g(p) = p. (existence of fixed point)

(ii) If the function g(x) is differentiable and g (x) is bounded

from above in the interval [a, b] and |g (x)| ≤ k < 1 for some

positive number k, then the fixed point p is unique.

(condition for divergence or oscillation)

(iii)For any p0 ∈ [a, b], the sequence [pn] defined as

pn = g(pn−1)

converges to the unique fixed point p in [a, b]. (condition for

convergence)

Sanjeev Kumar Verma Introduction to root finding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontorootfinding-201120180953/85/Introduction-to-root-finding-17-320.jpg)

![Fixed point theorem: application

Let g(x) = x2 + x − 2. Let x ∈ [0, 1]. Is g(x) ∈ [0, 1]? If yes,

there will be a fixed point in [0, 1].

Here, g(x) is a monotonically increasing function and

g(x) ∈ [−2, 0]. g(x) is completely outside the desired

interval! That was why you didn’t get the root in this case!

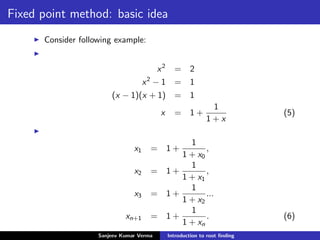

Now, take g(x) = 1 + 1

1+x . Let x ∈ [0, 1]. Is g(x) ∈ [0, 1]? If

yes, there will be a fixed point in [0, 1]. Otherwise, not.

Here, g(x) is monotonically decreasing function and

g(x) ∈ [1.5, 2]. So, there is no fixed point in [0, 1].

Is there a fixed point in [1, 2]?

If x ∈ [1, 2], then g(x) ∈ [1.33, 1.5] and hence g(x) ∈ [1, 2].

So, there will be a fixed point in [1, 2]!

Here, |g (x)| = 1

(1+x)2 < 1

4 which is always smaller than 1 in

[1, 2]. So, the fixed point is unique and there is guarantee of

convergence in this case.

Sanjeev Kumar Verma Introduction to root finding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontorootfinding-201120180953/85/Introduction-to-root-finding-18-320.jpg)

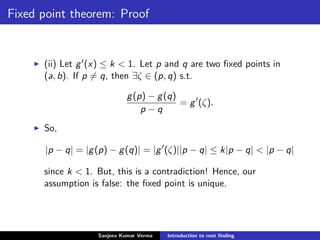

![Fixed point theorem: Proof

(i) If a or b is a fixed point, then g(a) = a or g(b) = b.

If a and b are not fixed points, but there is a fixed point in

[a, b], then a < g(a) and g(b) < b. Why?

Let h(x) = g(x) − x. Then, h(a) = g(a) − a > 0 and

h(b) = g(b) − b < 0. Does this remind you of something?

Bisection method! ∃p ∈ (a, b) s.t.

h(p) = 0 ⇒ g(p) − p = 0 ⇒ g(p) = p. Hence, there exists a

fixed point p ∈ (a, b).

Sanjeev Kumar Verma Introduction to root finding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontorootfinding-201120180953/85/Introduction-to-root-finding-20-320.jpg)

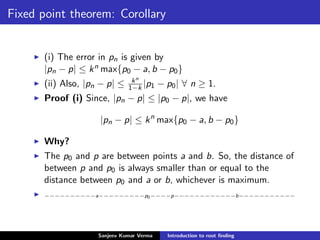

![Fixed point theorem: Proof

(iii) Since g maps [a, b] into itself, the series pn = g(pn−1)

defined and pn ∈ [a, b] ∀ n.

Since, |g (x)| < k for all x, for each n we have

|pn −p| = |g(pn−1)−g(p)| = |g (ζn)||pn−1 −p| ≤ k|pn−1 −p|.

for some ζn ∈ (a, b).

So, |pn − p| ≤ k|pn−1 − p| ≤ k2|pn−2 − p| and so on.

Finally, |pn − p| ≤ kn|p0 − p|.

In the limiting case when n approaches infinity, kn → 0 and so

|pn − p| → 0 or pn → p.

Sanjeev Kumar Verma Introduction to root finding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontorootfinding-201120180953/85/Introduction-to-root-finding-22-320.jpg)

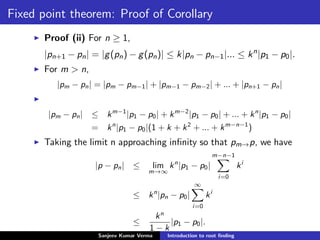

![Fixed point theorem: Application

Consider g(x) = 1 + 1

1+x . The fixed point of this function is

√

2.

|g (x)| = 1

(1+x)2 . For x ∈ [1, 2], we have |g (x)| < k = 1

4.

In six iterations, we have |p − pn| < 0.0002.

The speed of convergence, therefore, depends upon the

maximum value of |g (x)| viz. k.

In each iteration, the error in fixed point reduces by a factor

of k.

Ex. Can fixed point method converge at a slower rate than

bisection method?

Ans. For 0.5 < k < 1, fixed point method converges at a

slower rate than bisection method!

Lesson: Beware of simple minded thumb rules like bisection

method is slowest method. There is no way to escape

mathematical logic.

Sanjeev Kumar Verma Introduction to root finding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontorootfinding-201120180953/85/Introduction-to-root-finding-25-320.jpg)

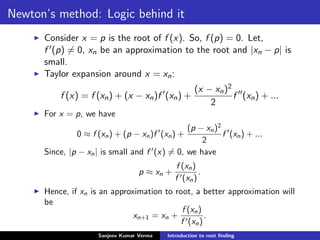

![Newton’s method: A theorem

Consider a continuous and differentiable function f (x) defined

over an interval [a, b]. If p ∈ [a, b] is such that f (p) = 0 and

f (p) = 0, then there exists a δ > 0 such that Newton’s

method generates a sequence {xn} converging to p for any

initial guess x0 ∈ [p − δ, p + δ].

This theorem tell us about the inherent danger in Newton’s

method. If the value of δ is too small and the initial guess is

chosen outside the interval [p − δ, p + δ], the sequence {xn}

will diverge.

To sense this danger beforehand in practical applications, we

should know what δ is.

Sanjeev Kumar Verma Introduction to root finding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontorootfinding-201120180953/85/Introduction-to-root-finding-31-320.jpg)

![Newton’s method: Proof of the theorem

Newton’s method for finding the root of f (x) is equivalent to the

fixed point method for finding the fixed point of the function

g(x) = x − f (x)

f (x) .

Here,

g (x) = 1 −

f (x)f (x) − f (x)f (x)

[f (x)]2

=

f (x)f (x)

[f (x)]2

.

Since, f (p) = 0, g (p) = 0. So, |g (x)| vanishes at x = p. In the

interval [p − δ, p + δ] around p, |g (x)| will increase. We can always

choose a sufficiently small δ so that |g (x)| ≤ k < 1.

Let’s show that the interval [p − δ, p + δ] maps g(x) into itself. For

all x ∈ [p − δ, p + δ], |x − p| < δ.

So,

|g(x)−p| = |g(x)−g(p)| = |g (ζ)||(x −p)| ≤ k|x −p| < |x −p| < d

which implies that g(x) is also contained in the interval

[p − δ, p + δ] because g (x) exists and |g(x)| ≤ k < 1.

Hence, the series pn = g(pn−1) will converge to p according to fixed

point theorem.

Sanjeev Kumar Verma Introduction to root finding](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontorootfinding-201120180953/85/Introduction-to-root-finding-32-320.jpg)