The document provides an introduction to robotics, including:

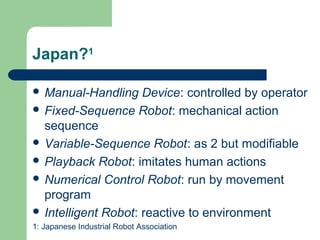

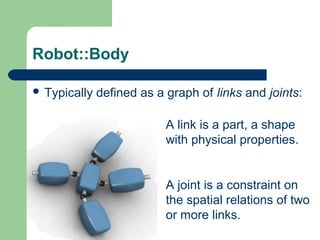

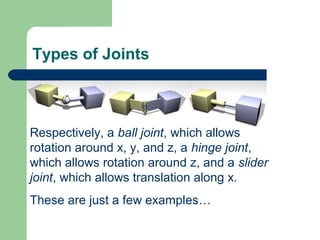

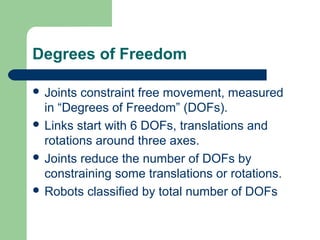

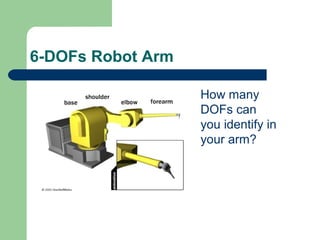

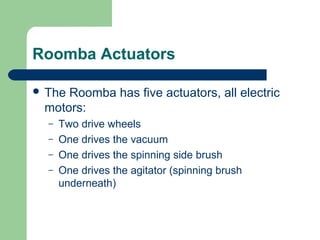

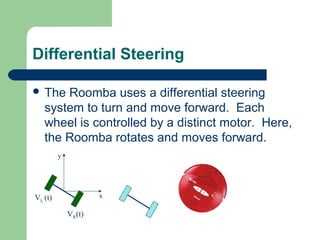

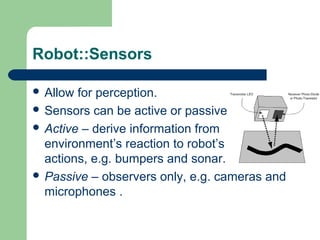

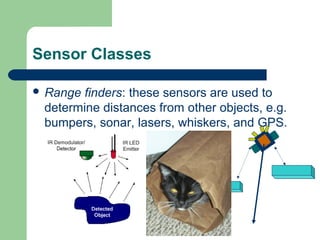

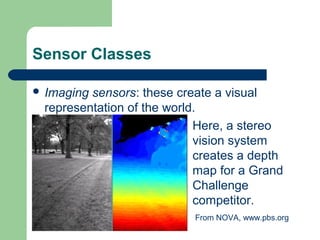

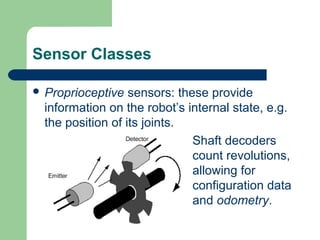

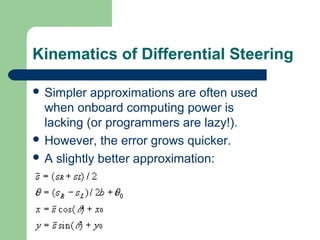

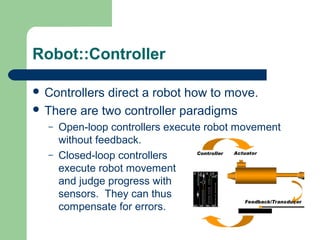

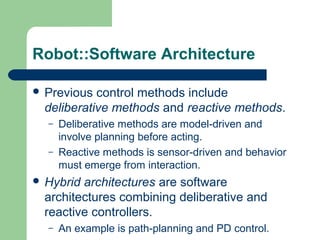

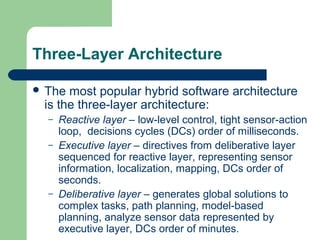

1) It discusses different definitions of robots and classes them based on their mobility and functions. It also explains the typical components of robots including their body, effectors, actuators, sensors, controller and software architecture.

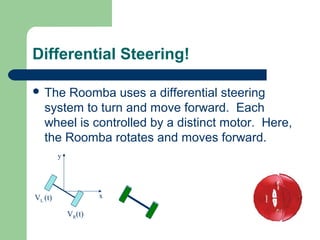

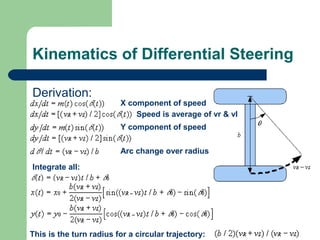

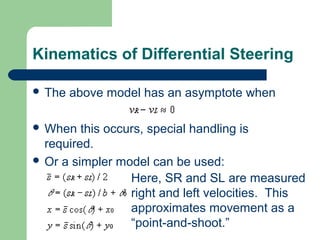

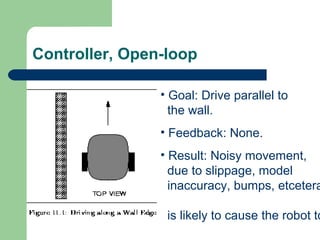

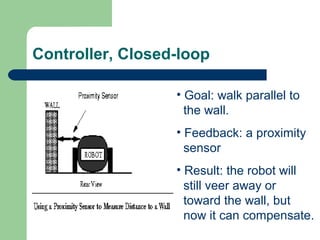

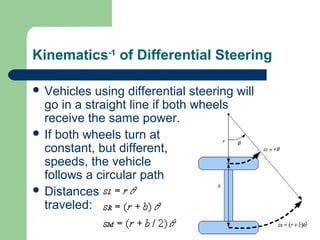

2) It uses the example of the Roomba vacuum cleaning robot to illustrate concepts like its actuators, sensors, differential steering and control.

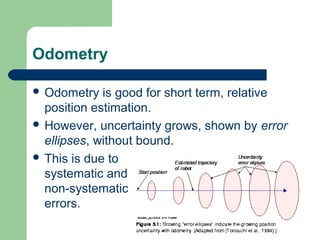

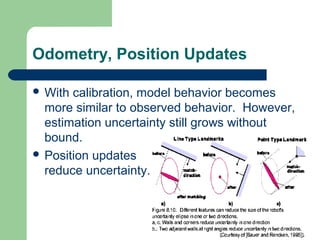

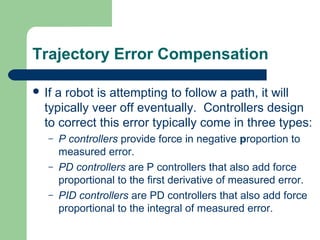

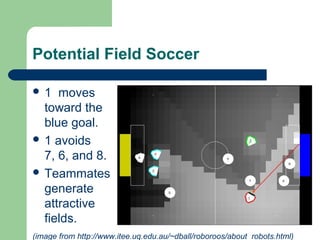

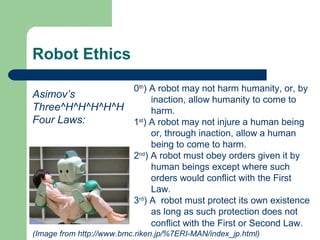

3) It introduces concepts in robotics like kinematics, forward and inverse kinematics, trajectory error compensation methods, potential field control and reactive control architectures. It also discusses Asimov's three laws of robotics.