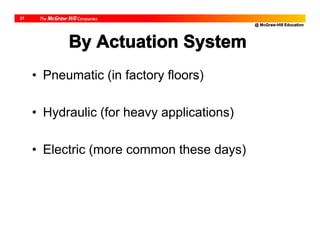

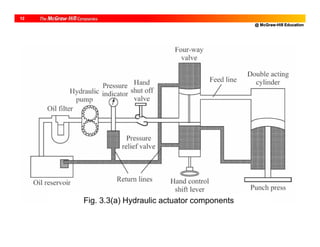

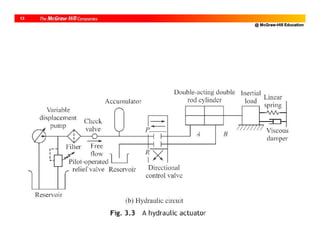

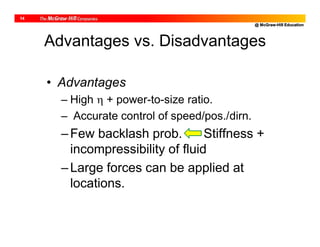

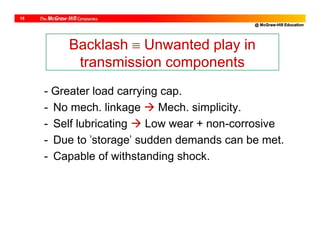

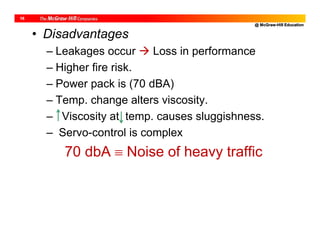

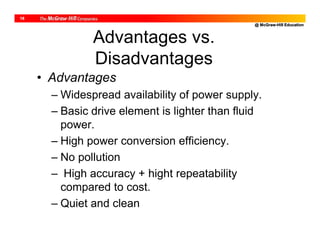

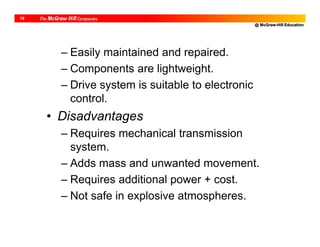

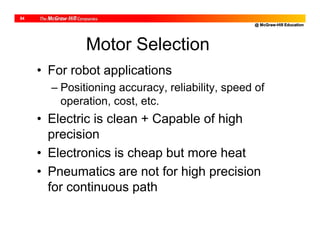

The document discusses different types of actuators used in robotics, including pneumatic, hydraulic, and electric actuators. Pneumatic actuators use compressed air and have advantages of low cost and easy control but lack precision. Hydraulic actuators can apply large forces with high power-to-size ratios but require complex servo control and have risks of leakage and fire. Electric actuators are now most common and include stepper motors for position control and DC motors for applications requiring higher power and torque control. The document compares characteristics of different actuator types for robotic applications.

![Laws of Robotics

• A robot must not harm a human being, nor

through inaction allow one to come to harm.

• A robot must always obey human beings,

unless that is in conflict with the 1st law.

• A robot must protect from harm, unless that is

in conflict with the 1st two laws.

• A robot may take a human being’s job but it

may not leave that person jobless. [Fuller(1999)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-2-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

13

Recognition Subsystem

(ii) Analog-to-Digital

Converter (ADC)

- Electronic device

(i) Sensors (Essentially transducers)

- Converts a signal

to another

Fig. 2.8 An analog-to-digital converter

[Courtesy: http://www.eeci.com/adc-16p.htm]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-27-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

14

Control Subsystem

(i) Digital Controller

- CPU, Memory, Hard disk (to store programs)

Controller

Robot

Sensor

Desired end-effector

trajectory

Driving

input

Actual end-effector

configuration

Joint displacement

and velocity

Fig. 2.9 Control subsystem

[Courtesy: http://www.abb.com/Product/seitp327/f0cec80774b0b3c9c1256fda00409c2c.aspx]

(a) Control scheme of a robot (b) ABB Controller](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-28-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

15

Control Subsystem (contd.)

(ii) Digital-to-Analog Converter (DAC)

(iii) Amplifier

- Amplify weak commands from DAC

Fig. 2.10 A digital-to-analogue converter

[Courtesy: http://www.eeci.com]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-29-320.jpg)

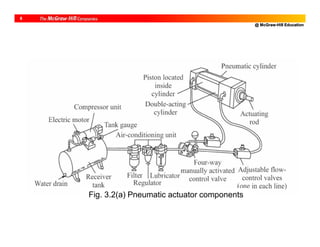

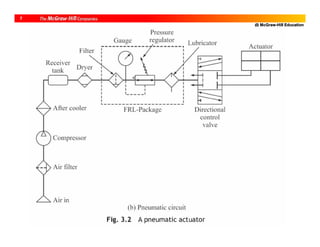

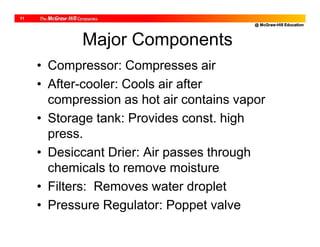

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

5

• One of fluid devices

• Uses compressed air [1-7 bar; ~.1 MPa/bar]

• Components

1) Compressor; 2) After-cooler; 3) Storage tank;

4) Desiccant driers; 5) Filters; 6) Pressure

regulators; 7) Lubricants; 8) Directional control

valves; 9) Actuators

Pneumatic Actuators](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-49-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

34

Permanent Magnet (PM) Motor

• Two configurations

– Cylindrical [Common in industrial robots]

– Disk](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-78-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

35

Permanent Magnet (PM) Motor (cont.)

• No field coils

• Field is by permanent magnets (PM)

• Some PM has coils for recharge

• Torque Armature current [Const. flux]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-79-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

46

Classification of an AC Motor

• Single-phase [Low-power requirements]

– Induction

– Synchronous

• Poly-phase (typically 3-phase) [High-

power requirements]

– Induction

– Synchronous

• Induction motors are cheaper Widely

used](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-90-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

24

xp

zp

ypF][p . . . (5.8)

[ ] , [ ] , and [ ]

1 0 0

0 1 0

00 1

F F Fx y z

. . . (5.10)

Position Description

p = px x + py y + pz z . . . (5.9)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-133-320.jpg)

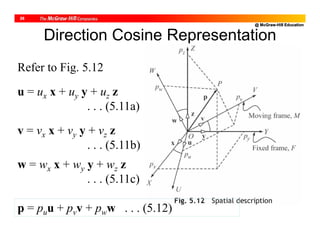

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

27

p = (puux + pvvx + pwwx)x + (puuy + pvvy + pwwy)y

+ (puuz + pvvz + pwwz)z . . . (5.13)

px = uxpu + vxpv + wxpw . . . (5.14a)

py = uypu + vypv + wypw . . . (5.14b)

pz = uzpu + vzpv + wzpw . . . (5.14c)

Substitute eqs. (5.11a-c) into eq. (5.12)

[p]F = Q [p]M . . . (5.15)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-136-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

28

[p]F = Q [p]M . . . (5.15)

xwxvxu

zwzvzu

ywyvyuQpp

TTT

TTT

TTT,][,][

x

w

x

v

x

u

z

w

z

v

z

u

y

w

y

v

y

u

F

u

p

w

p

v

p

x

p

z

p

y

p M

.. . (5.16)

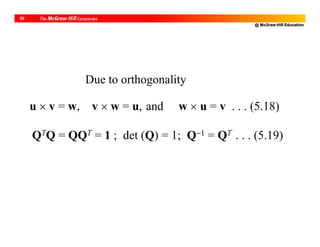

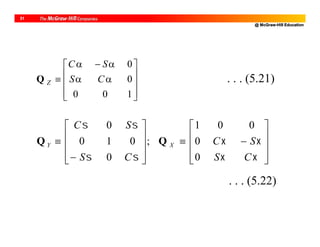

uTu = vTv = wTw = 1, and

uTv(vTu) = uTw(wTu) = vTw(wTv) = 0 … (5.17)

Q is called Orthogonal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-137-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

30

[ ,

[ ] ,

[ ]

0

0

0

0

1

u]

v

w

F

F

F

Cα

Sα

Sα

Cα

. . . (5.20)

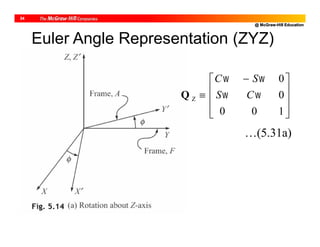

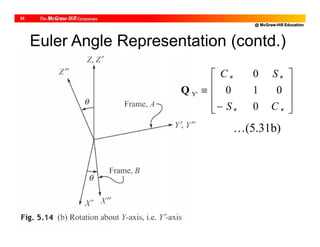

Example 5.6 Elementary Rotations (Fig. 5.13a)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-139-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

32

pz = pw . . . (5.25)

[p]F = QZ [p]M . . . (5.26)

py = pu S + pv C . . . (5.24)

px = pu C pv S . . . (5.23)

Example 5.8 Coordinate Transformation (Fig. 5.13b)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-141-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

33

px = px C py S . . . (5.27)

py = px S + py C . . . (5.28)

pz = pz . . . (5.29)

Example 5.9 Vector Rotation (Fig. 5.13c)

[p]F = QZ [p]F … (5.30)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-142-320.jpg)

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

43

p = o + p . . . (5.34)

[p]F = [o]F + Q[p’]M . . . (5.35)

1

][

1

][

1

][

T

F MF poQp

0

. . . (5.36)

MF ][][ pTp . . . (5.37)

Homogenous Transformation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-152-320.jpg)

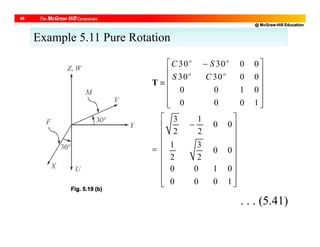

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

44

TTT 1 or T1 TT . . . (5.38)

1

][

T

TT

1

0

oQQ

T F

. . . (5.39)

1000

1100

2010

0001

T

. . . (5.40)

Example 5.10 Pure Translation

T: Homogenous transformation matrix (4 4)

Fig. 5.19 (a)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-153-320.jpg)

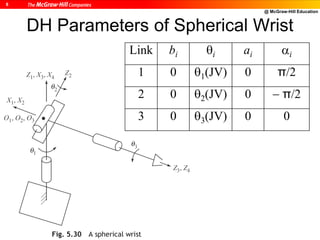

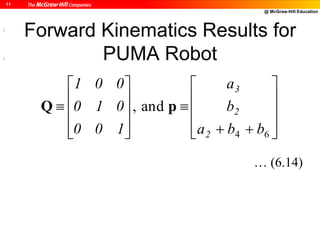

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

10

DH Parameters of PUMA Robot

i bi i ai i

1 0 1 (JV) [0] 0 -/2

2 b2 2 (JV) [-/2] a2 0

3 0 3 (JV) [/2] a3 /2

4 b4 4 (JV) [0] 0 -/2

5 0 5 (JV) [0] 0 /2

6 b6 6 (JV) [0] 0 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-189-320.jpg)

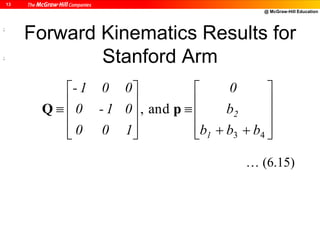

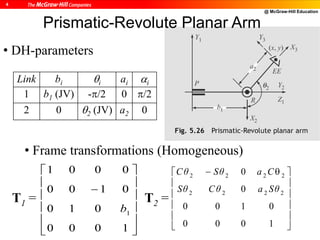

![@ McGraw-Hill Education

12

DH Parameters of Stanford Arm

i bi i ai i

1 b1 1 (JV) [0] 0 -/2

2 b2 2 (JV) [] 0 -/2

3 b3

(JV)

0 0 0

4 b4 4 (JV) [0] 0 /2

5 0 5 (JV) [0] 0 -/2

6 0 6 (JV) [0] 0 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/roboticsdone-171104154009/85/Robotics-done-191-320.jpg)