This document provides an introduction to fatigue, including:

- Fatigue occurs when a component is subjected to fluctuating stresses and fails at a stress lower than its static strength.

- It accounts for 90% of mechanical failures and occurs suddenly without warning.

- Three factors are needed for fatigue failure: a maximum stress, stress variation, and sufficient number of cycles.

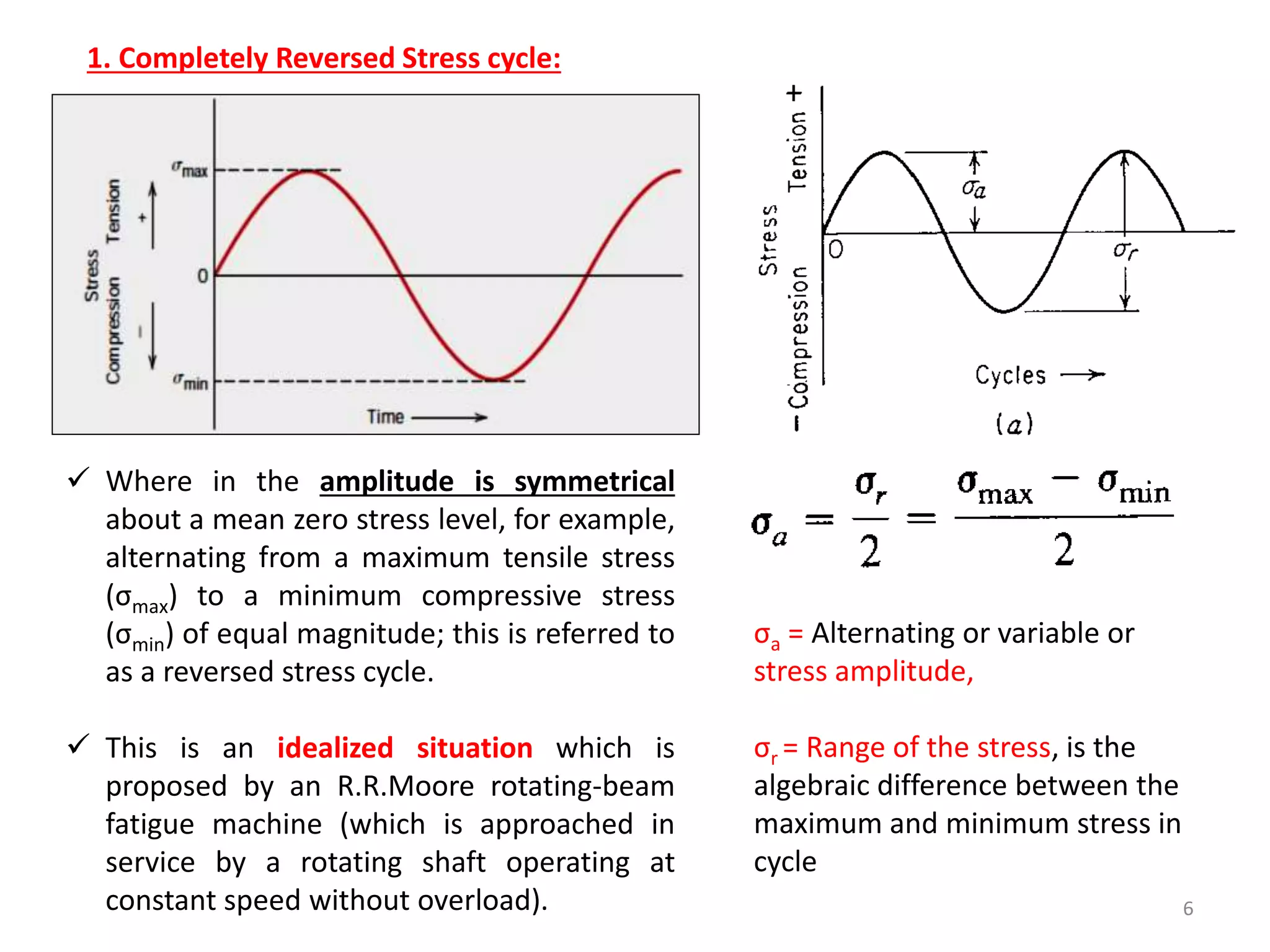

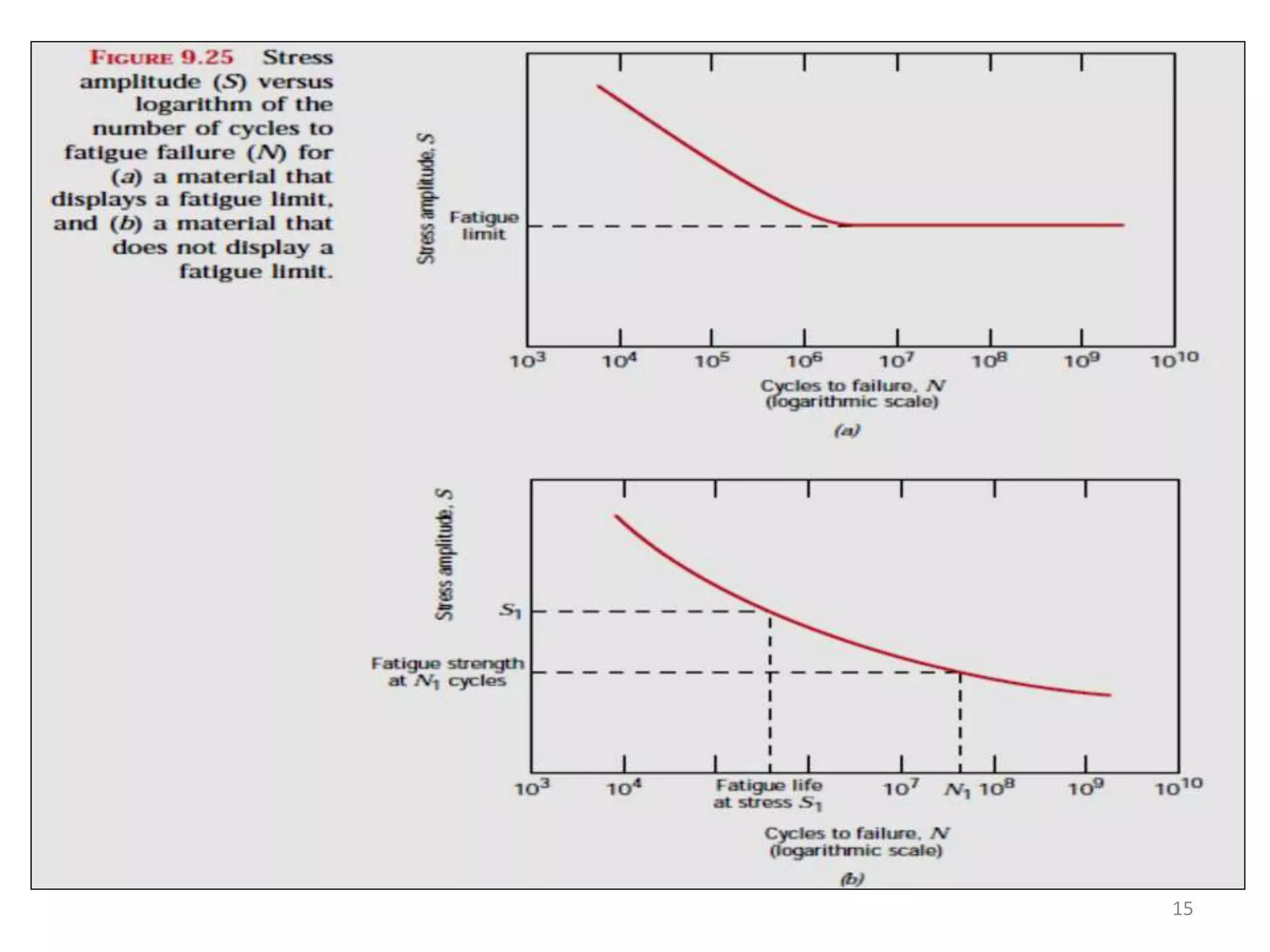

- Fatigue testing involves subjecting specimens to cyclic stresses and recording the number of cycles until failure to generate an S-N curve.

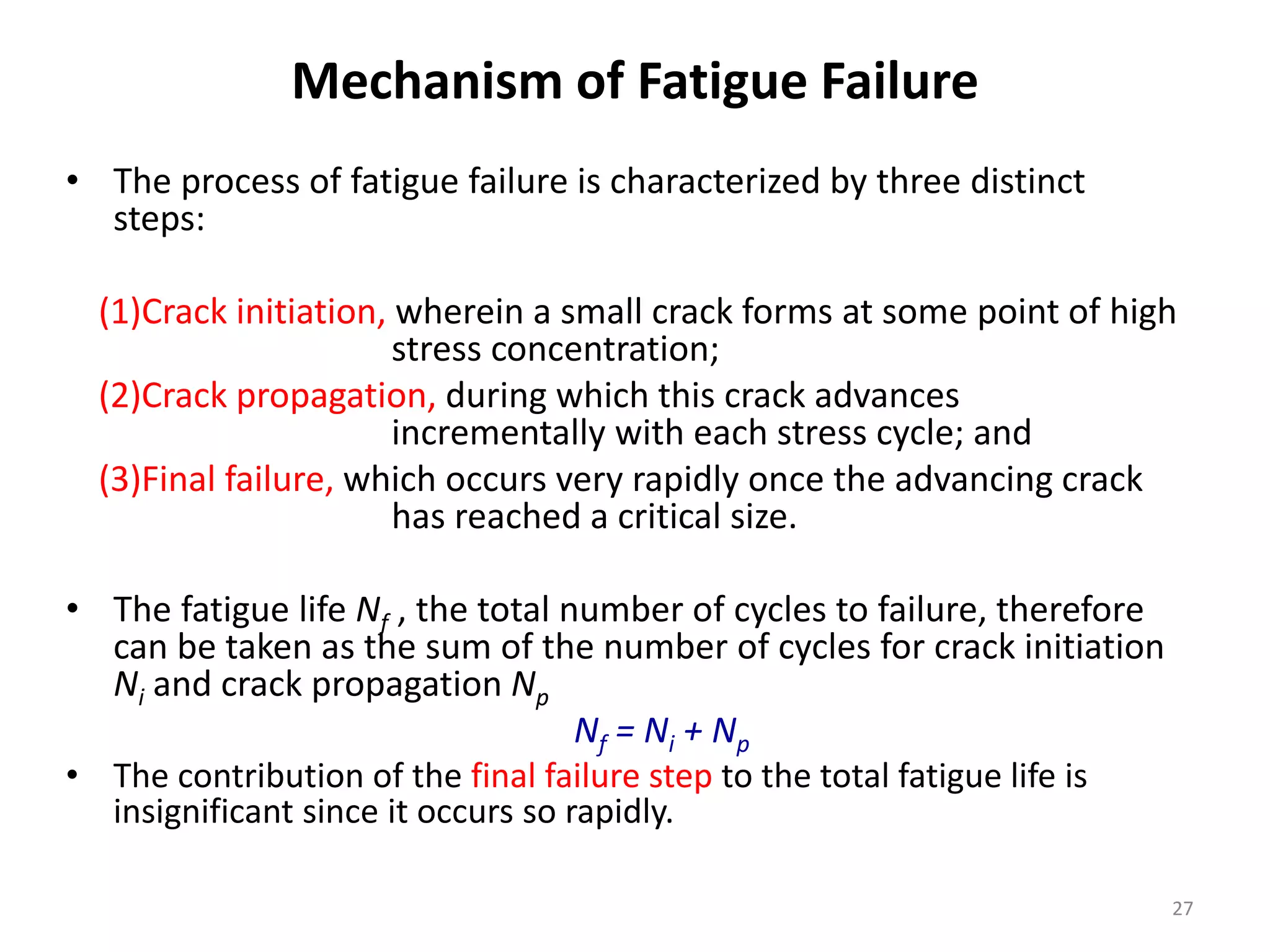

![• Knowledge of crack growth rate is of assistance in designing

component and in nondestructive evaluation to determine if a crack

poses imminent danger to the structure.

• One approach to this problem is to estimate the number of cycle

required before failure occurs. By rearranging Equation 01 and

substituting for ∆𝐾: and integrate this b/w the initial size of the crack

and the crack size required for fracture to occur, we find that.

𝑁 =

2[(𝑎 𝑐)

2−𝑛

2 − 𝑎𝑖

2−𝑛

2 ]

2 − 𝑛 𝐶Y 𝑛∆σ 𝑛π 𝑛/2

• ai = initial Flaw size

• ac = flaw size required to fracture.

• C and n = are empirical constant depends upon the material.

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fatigue-160316060415/75/Fracture-Mechanics-Failure-Analysis-Lecture-Fatigue-45-2048.jpg)