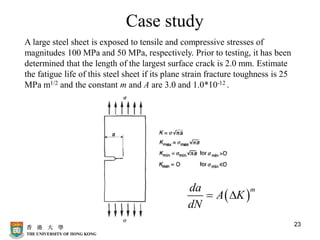

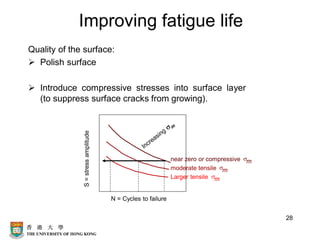

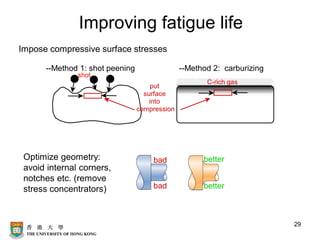

The document outlines the service behavior of materials, focusing on fatigue, corrosion, engineering plastics, and composites. It explains the concept of fatigue as a failure mechanism under dynamic and fluctuating stresses, detailing testing methods, fatigue behavior, mechanisms, and the importance of surface quality in fatigue life. Additionally, it discusses the environmental effects on fatigue, such as thermal and corrosion impacts, and provides strategies for improving fatigue life.

![2

Topics covered in this course

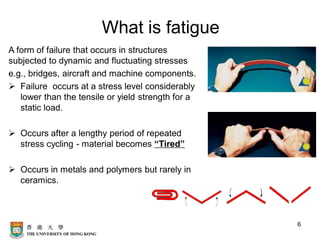

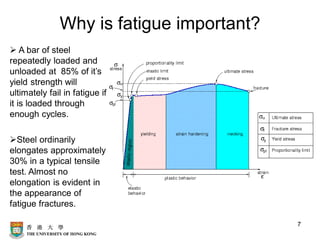

• Fatigue

• Corrosion

• Engineering plastics

• Composites

• Creep

• Fracture

References:

[1] M.F. Ashby and D.R.H. Jones, Engineering Materials 1: An

Introduction to Their Properties and Applications, Pergmon Press

[2] W.D. Callister, Materials Science and Engineering: An Introduction,

John Wiley & Sons, INC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-230723034947-bb1d3432/85/1-Fatigue-pdf-2-320.jpg)