This document discusses electric motors and DC motors specifically. It provides information on:

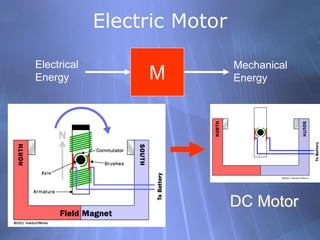

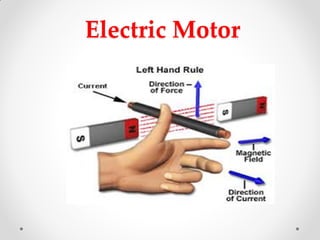

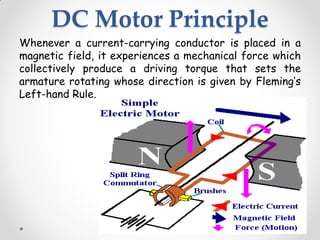

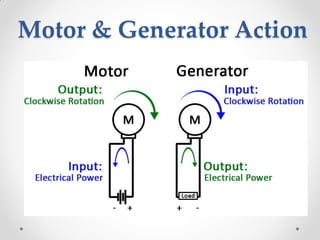

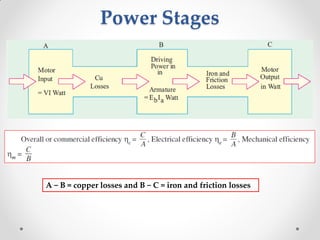

1. The basic components and principles of DC motors, including how a current-carrying coil in a magnetic field produces torque.

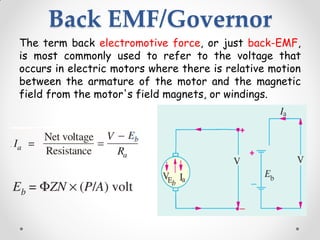

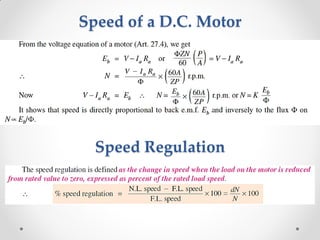

2. How back electromotive force (EMF) regulates motor speed as the armature rotates in the magnetic field.

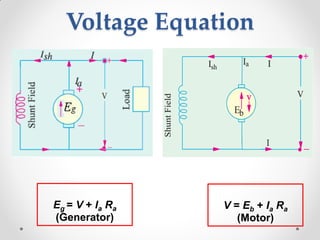

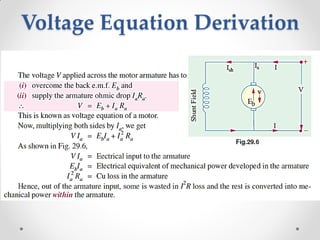

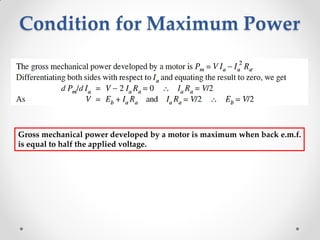

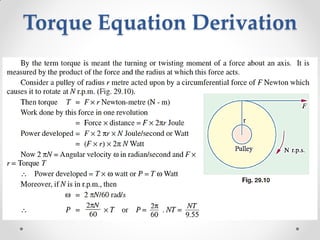

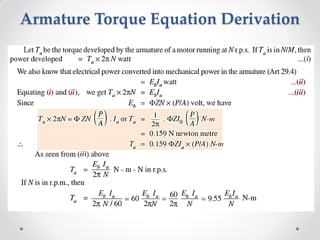

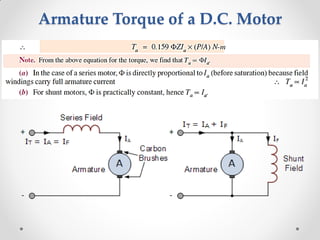

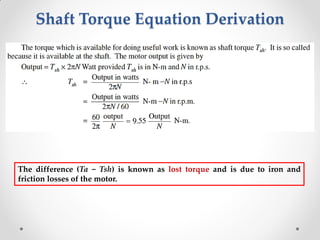

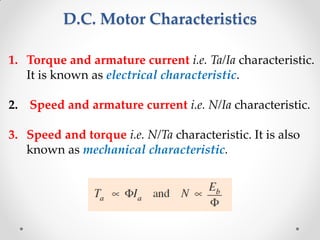

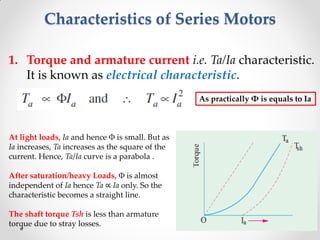

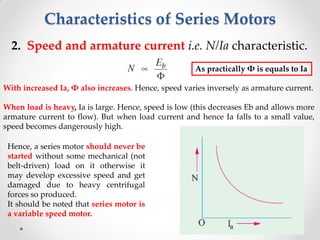

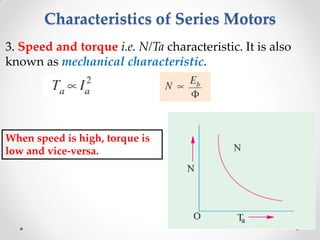

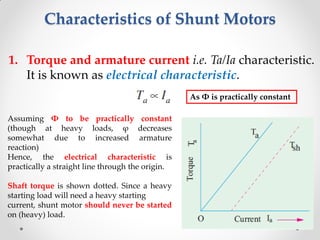

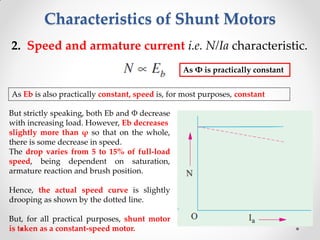

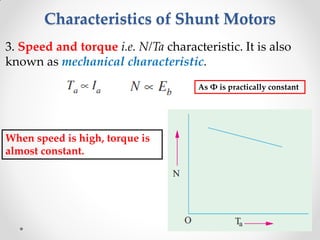

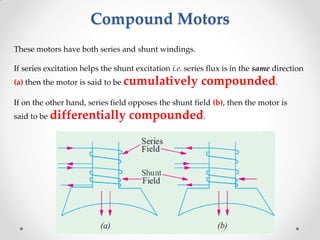

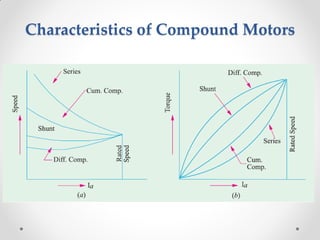

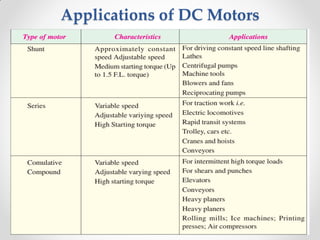

3. Equations for motor voltage, torque, speed, and characteristics like torque-current curves for series, shunt, and compound motors.

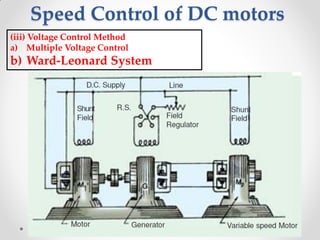

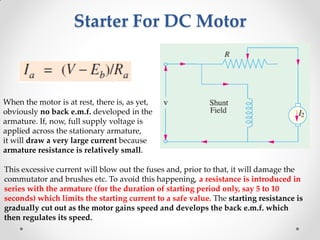

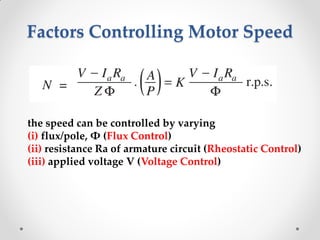

4. Methods for controlling motor speed including changing the flux, armature resistance, or applied voltage. Starters are also discussed to limit starting current.

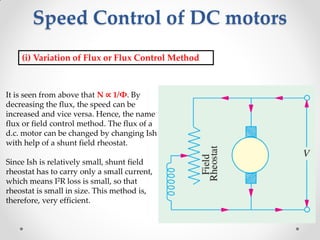

![Speed Control of DC motors

(ii) Armature or Rheostatic Control Method

This method is used when speeds below the no-load speed are required. As the supply

voltage is normally constant, the voltage across the armature is varied by inserting a

variable rheostat or resistance (called controller resistance) in series with the armature

circuit as shown in Fig. (a).

As controller resistance is increased, potential difference(p.d.) across the armature is

decreased, thereby decreasing the armature speed. For a load constant torque, speed is

approximately proportional to the p.d. across the armature. From the speed/armature

current characteristic [Fig. (b)], it is seen that greater the resistance in the armature

circuit, greater is the fall in the speed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eece259dcmotor-160510181804/85/Eece-259-dc-motor-28-320.jpg)