This document discusses bronchiectasis, defined as abnormal permanent dilation of the bronchi. It covers the types (tubular, varicose, cystic), diagnosis (clinical features and chest CT), pathophysiology (Cole's vicious cycle hypothesis involving infection and inflammation causing tissue damage), etiologies (post-infectious, mucociliary disorders like cystic fibrosis, immunodeficiency, rheumatological conditions), and relationship to COPD (similar inflammation and airflow obstruction features). The document is intended to provide an overview of bronchiectasis for medical students.

![Introduction

• Bronchiectasis :defined by the presence of permanent and abnormal

dilation of the bronchi.[1,2]

• Bronchiectasis is an uncommon disease, most often secondary to an

infectious process, that results in the abnormal and permanent distortion

of one or more of the conducting bronchi or airways.

• Bronchiectasis shares many clinical features with COPD, including inflamed and easily collapsible

airways, obstruction to airflow, and frequent office visits and hospitalizations.

• The diagnosis is usually established clinically on the basis of chronic daily

cough with viscid sputum production, and radiographically by the presence

of bronchial wall thickening and luminal dilatation on chest CT scans [ 3].

1. Barker AF. Bronchiectasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1383–1393.

2. King PT, Holdsworth SR, Freezer NJ, Villanueva E, Holmes PW. Characterisation of the onset and presenting clinical features of adult bronchiectasis. Respir Med.

2006;100:2183–2189.

3. Barker AF. Bronchiectasis. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1383.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-2-320.jpg)

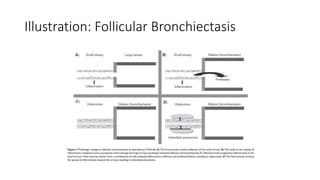

![Types

In 1950, Reid categorized bronchiectasis as having three main phenotypes:[1]

• 1) tubular(cylindrical) :characterized by smooth dilation of the bronchi;

• 2) varicose (bulbous):in which the bronchi are dilated with multiple indentations;

• 3) cystic (saccular/balloon appearance):in which dilated bronchi terminate in blind ending sacs.

Whitwell classified bronchiectasis into three different types:

• Follicular, Saccular, and Atelectatic. Follicular bronchiectasis was the dominant form and this

corresponded to tubular bronchiectasis (the main form commonly seen).

• Bronchiectasis has been described as being localized (ie, confined to one lobe) or generalized.

Most commonly it is generalized and seems to be most common in the lower lobes.[2,3] The

involvement of the lower lobes may reflect gravity dependent retention of infected secretions.

1. Reid LM. Reduction in bronchial subdivision in bronchiectasis. Thorax. 1950 Sep. 5(3):233-47.

2. King PT, Holdsworth SR, Freezer NJ, Villanueva E, Holmes PW. Characterisation of the onset and presenting clinical features of adult bronchiectasis. Respir Med. 2006;100:2183–2189.

3. Field E. Bronchiectasis: a long-term follow-up of medical and surgical cases from childhood. Arch Dis Child. 1961;36:587–603.

• Can also be differentiated as :Congenital & Acquired or Cystic fibrosis associated and Non CF Bronchiectasis.

• If Associated with Post fibrosis: Traction Bronchiectasis

• Without Must expectorant: Dry Bronchiectasis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-3-320.jpg)

![Cole’s “vicious cycle hypothesis”[1]

• Cole proposed that an environmental insult often on a background of

genetic susceptibility (impaired mucociliary clearance) resulting in

persistence of microbes in the sinobronchial tree and microbial

colonization.

• The microbial infection caused chronic inflammation resulting in

tissue damage and impaired mucociliary motility.

• In turn this led to more infection with a cycle of progressive

inflammation causing lung damage.

• The current view is that the two factors required for the development

of this condition are persistent infection and a defect in host defense.

1. Cole PJ. Inflammation: a two-edged sword – the model of bronchiectasis.Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1986;147:6–15.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-5-320.jpg)

![Path….continue

• The dominant cell types involved in the inflammatory process in

bronchiectasis are neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages.[1]

Neutrophils are the most prominent cell type in the bronchial lumen [2],

and release mediators, particularly proteases/elastase which cause

bronchial dilation (ie, bronchiectasis).[3]

• The infiltrate in the cell wall is predominantly composed of macrophages

and lymphocytes.[2]

• Studies have reported that the main lymphocyte is the T cell [4] and these

are cells that are likely to produce the lymphoid follicles described by

Whitwell.

1. Fuschillo S, De Felice A, Balzano G. Mucosal inflammation in idiopathic bronchiectasis: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:396–406.

2. Eller J, Lapa e Silva JR, Poulter LW, Lode H, Cole PJ. Cells and cytokines in chronic bronchial infection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;725:331–345.

3. Khair OA, Davies RJ, Devalia JL. Bacterial-induced release of inflammatory mediators by bronchial epithelial cells. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:1913–1922.

4. Lapa e Silva JR, Guerreiro D, Noble B, Poulter LW, Cole PJ. Immunopathology of experimental bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1989;1:297–304.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-6-320.jpg)

![Etiologic factors: Post infectious….continue

• One well characterized form of bronchiectasis occurs in the context of

mycobacterial infection and this form is particularly prevalent in the

right middle lobe with nontuberculous mycobacterium.[1,2,3] The

mechanism of this form of bronchiectasis appears to arise from lymph

node obstruction.

• The acute infection causes enlargement of peribronchial nodes which

obstruct the bronchus and result in secondary bronchiectasis. This

bronchial dilation persists when the mycobacterial infection resolves

and the nodes return to normal size.

1. Whitwell F. A study of the pathology and pathogenesis of bronchiectasis. Thorax. 1952;7:213–219.

2. Lynch DA, Simone PM, Fox MA, Bucher BL, Heinig MJ. CT features of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1995;19:353–360.

3. Fujita J. Radiological findings of non-tuberculous mycobacteria respiratory infection. Kekkaku. 2003;78:557–561.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-9-320.jpg)

![Etiologic factors: Muco-ciliary clearance

• Muco-ciliary clearance is a key defence mechanism against pulmonary infection.

Its compromise is important in the development of the vicious cycle of

bronchiectasis as proposed by Cole.[1]

• Cystic fibrosis is associated with defective muco-ciliary clearance .

• The most prominent cilial disorder is primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) which

combines upper and lower respiratory tract infection, male infertility and in

approximately 50%, situs inversus. PCD arises primarily from a defect in the

dynein arms which are necessary for normal cilial beating. [2]

• Bronchiectasis is a prominent manifestation of PCD.

• Young’s syndrome is another condition in which the primary defect is thought to

be defective mucous function.[3]

1. Cole PJ. Inflammation: a two-edged sword – the model of bronchiectasis. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1986;147:6–15.

2. Omran H, Kobayashi D, Olbrich H, et al. Ktu/PF13 is required for cytoplasmic pre-assembly of axonemal dyneins. Nature. 2008;456: 611–616.

3. Friedman KJ, Teichtahl H, De Kretser DM, et al. Screening Young syndrome patients for CFTR mutations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1353–1357.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-10-320.jpg)

![Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

• There is also some overlap in the pathology of COPD and

bronchiectasis. Both conditions have neutrophils and T lymphocytes

as the predominant inflammatory cell,[1,2] protease release causes

pulmonary damage and lymphoid follicles have a role in airflow

obstruction.[3,4]

1. Fuschillo S, De Felice A, Balzano G. Mucosal inflammation in idiopathic bronchiectasis: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:396–406.

2. Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:269–280.

3. Whitwell F. A study of the pathology and pathogenesis of bronchiectasis. Thorax. 1952;7:213–219.

4. Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2645–2653.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-11-320.jpg)

![Etiologic factors:

Rheumatological/inflammatory conditions

• There is a well described association between bronchiectasis and rheumatoid arthritis.

• In rheumatoid arthritis the incidence of bronchiectasis has been described to be 1%–3%.

• Recent studies of patients with RA have described the prevalence of bronchiectasis on

HRCT in such patients as being up to 30%.[1]

• Bronchiectasis may also occur in association with Sjogren’s syndrome63 and Churg–

Strauss syndrome.[2]

• It is possible that immune suppression may predispose to chronic airway infection.[3]

• Bronchiectasis also occurs in subjects with inflammatory bowel disease.[4]

1. Cortet B, Flipo RM, Remy-Jardin M, et al. Use of high resolution computed tomography of the lungs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:815–819.

2. Larche MJ. A short review of the pathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:132–135.

3. King P. Churgh-Strauss syndrome and bronchiectasis. Respir Med Extra.2007;3:26–28.

4. Black H, Mendoza M, Murin S. Thoracic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Chest. 2007;131:524–532.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-12-320.jpg)

![Etiologic factors: Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency

• Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency is associated with increased risk of

COPD and bronchiectasis.

• Parr and colleagues studied the prevalence of airways disease in AAT

deficient subjects and found that 70 of 74 subjects had radiological

evidence of bronchiectasis and 20 subjects were classified as having

clinically significant bronchiectasis.[1]

1. Parr DG, Guest PG, Reynolds JH, Dowson LJ, Stockley RA. Prevalence and impact of bronchiectasis in alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1215–1221.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-13-320.jpg)

![Microbiology

• A large number of different pathogens have been isolated in studies of

microbiologic flora in bronchiectasis. The main findings from recent studies have

been that Haemophilus influenza is the most common pathogen (range 29%–

70%) followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (range 12%–31%).[1,2] and others

include Moxarella.

• The role of viral infection in bronchiectasis is not well defined. Becroft[3]

identified adenovirus as a risk factor for the development of bronchiectasis in

young children.

• Viral infections have a role in exacerbations of COPD but this has not been

defined for bronchiectasis.[4]

1. Nicotra MB, Rivera M, Dale AM, Shepherd R, Carter R. Clinical, pathophysiologic, and microbiologic characterization of bronchiectasis in an aging cohort. Chest.

1995;108:955–961.

2. Pasteur MC, Helliwell SM, Houghton SJ, et al. An investigation into causative factors in patients with bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1277–1284.

3. Becroft DM. Bronchiolitis obliterans, bronchiectasis, and other sequelae of adenovirus type 21 infection in young children. J Clin Pathol. 1971;24:72–82.

4. Seemungal T, Harper-Owen R, Bhowmik A, et al. Respiratory viruses, symptoms, and inflammatory markers in acute exacerbations and stable chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2001;164:1618–1623.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-14-320.jpg)

![Cigarette smoking

• A causal role for cigarette smoking in bronchiectasis has not been

demonstrated conclusively. However, smoking and repeated

infections may worsen pulmonary function and accelerate the

progression of disease that is already present [ 1 ].

1. Popa V. Airway obstruction in adults with recurrent respiratory infections and IgG deficiency. Chest 1994; 105:1066.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-15-320.jpg)

![CT Findings [1]

The main diagnostic features are:

1) internal diameter of a bronchus is wider than its adjacent pulmonary

artery;

2) failure of the bronchi to taper; and

3) visualization of bronchi in the outer 1–2 cm of the lung fields

1. McGuinness G, Naidich DP. CT of airways disease and bronchiectasis.Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:1–19.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-19-320.jpg)

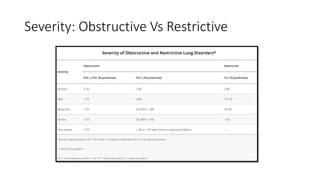

![Lung function tests

• Pulmonary function testing is used for functional assessment of

impairment due to bronchiectasis.

• Spirometry before and after the administration of a bronchodilator is

satisfactory in most patients.

• Obstructive impairment (ie, reduced or normal forced vital capacity

[FVC], low forced expiratory volume [FEV1], and low FEV1/FVC)is the

most frequent finding.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-21-320.jpg)

![Prevention

• Less clear and not well studied is the role of so-called preemptive,

suppressive, or preventive antibiotic regimens. Examples of such regimens

are listed in order of increasing complexity and expense.

• Strategy 1 – Daily oral antibiotic Rx, such as ciprofloxacin (500-

1500 mg/day in 2-3divided doses) [ 1 ]. Alternatively, a similar antibiotic

given for 7-14 d/mnth.

• Strategy 2 – Daily or 3X wkly use of a macrolide antibiotic, a modification

of Strategy 1 that is efficacious in the management of cystic fibrosis [ 2 ]. The

benefit of this approach was demonstrated in a double-blind trial that randomly assigned 19 patients with

bronchiectasis to receive erythromycin (500 mg, twice per day) or placebo for eight weeks [ 3 ].

1. Rayner CF, Tillotson G, Cole PJ, Wilson R. Efficacy and safety of long-term ciprofloxacin in the management of severe bronchiectasis. J Antimicrob Chemother 1994; 34:149.

2. Saiman L, Marshall BC, Mayer-Hamblett N, et al. Azithromycin in patients with cystic fibrosis chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;

290:1749.

3. Tsang KW, Ho PI, Chan KN, et al. A pilot study of low-dose erythromycin in bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J 1999; 13:361.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bronchiectasis-151221131010/85/Bronchiectasis-26-320.jpg)