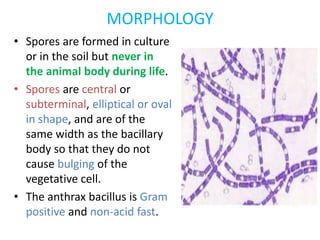

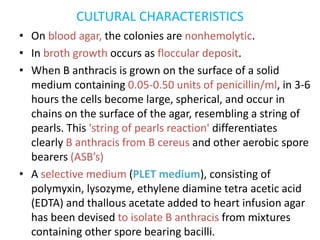

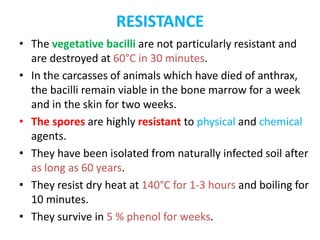

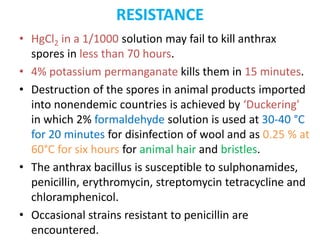

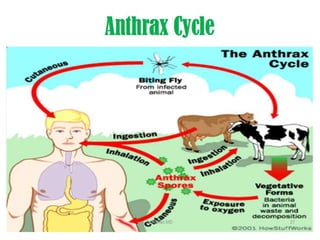

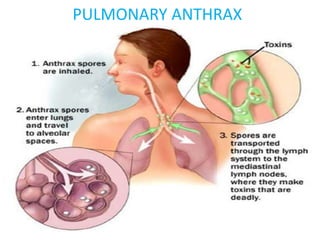

Bacillus is a genus of rod-shaped, Gram-positive bacteria that can form dormant endospores. The document focuses on Bacillus anthracis, which causes anthrax. It describes the morphology, cultural characteristics, virulence factors, and methods of diagnosis and prevention of B. anthracis. Key points include that B. anthracis forms encapsulated, non-motile rods and terminal spores. The anthrax toxins are composed of lethal factor, edema factor, and protective antigen, which combine to cause disease. Diagnosis involves microscopy, culture, and serology. Prevention for humans involves vaccination with anthrax toxoid and occupational hygiene, while animals are vaccinated with attenuated spore