Atmospheric corrosion is a major cause of degradation and failure of metals exposed to outdoor and indoor environments. It accounts for significant economic losses as corroded metals must be replaced. While atmospheres are typically classified as industrial, marine, rural, or indoor, most real-world environments involve mixtures of conditions. Atmospheric corrosion occurs via localized corrosion cells and is influenced by factors like pollution, humidity, and proximity to salt or chemical sources. Proper material selection and protection methods are needed to prevent atmospheric corrosion in various environmental conditions.

![ Atmospheric corrosion has been reported to account for more

failures in terms of cost and tonnage than any other type of material

degradation processes. This particular type of material degradation

has recently received more attention, particularly by the aircraft

industry, since the Aloha incident in 1988, when a Boeing 737 lost a

major portion of the upper fuselage in full flight at 7300 m [1].

All of the general types of corrosion attack occur in the atmosphere.

Since the corroding metal is not bathed in large quantities of electrolyte,

most atmospheric corrosion operates in highly localized corrosion cells,

sometimes producing patterns difficult to explain as in the example of

the rusting galvanized roof shown in Fig. 9.1.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/newmicrosoftpowerpointpresentation-151119120623-lva1-app6892/85/Atmospheric-Corrosion-3-320.jpg)

![ While atmospheres have been traditionally classified into four basic

types, most environments are in fact mixed and present no clear

demarcation. Furthermore, the type of atmosphere may vary with the

wind pattern, particularly where corrosive pollutants are present, or

with local conditions (Fig. 9.2) [2].

1. Industrial

2. Marine

3. Rural

4. Indoor](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/newmicrosoftpowerpointpresentation-151119120623-lva1-app6892/85/Atmospheric-Corrosion-6-320.jpg)

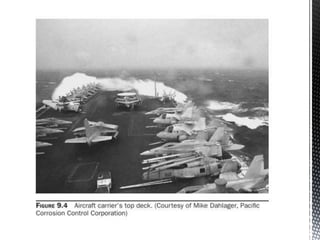

![ Marine

A marine atmosphere is laden with fine particles of sea mist carried

by the wind to settle on exposed surfaces as salt crystals. The quantity

of salt deposited may vary greatly with wind velocity and it may, in

extreme weather conditions, even form a very corrosive salt crust,

similar to what is experienced on a regular basis by sea patrolling

aircraft or helicopters [Figs. 9.3(a) and (b)].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/newmicrosoftpowerpointpresentation-151119120623-lva1-app6892/85/Atmospheric-Corrosion-10-320.jpg)