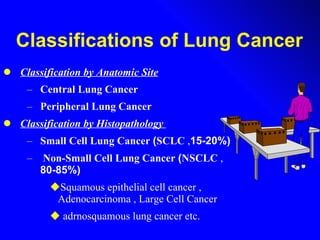

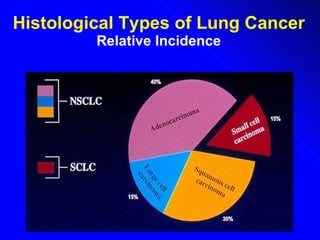

The document discusses lung cancer (bronchogenic carcinoma), including:

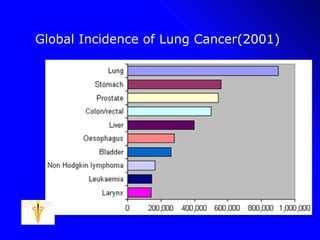

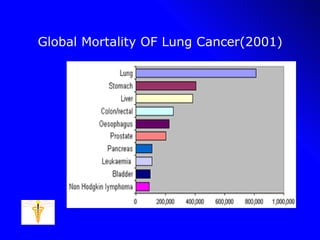

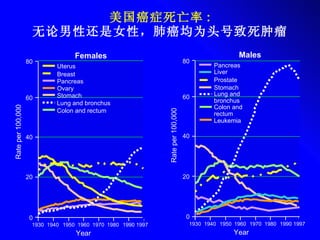

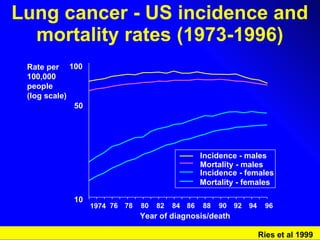

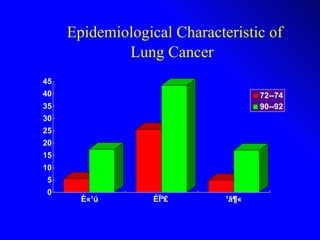

1. It provides epidemiological data on global incidence and mortality of lung cancer.

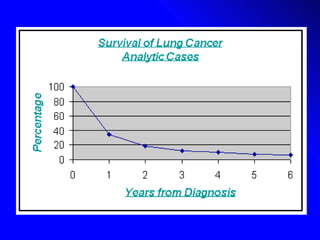

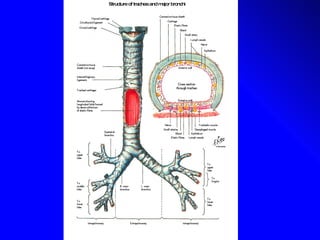

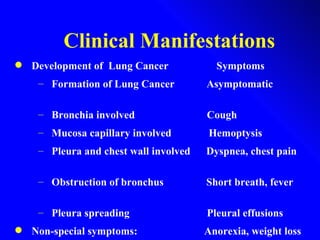

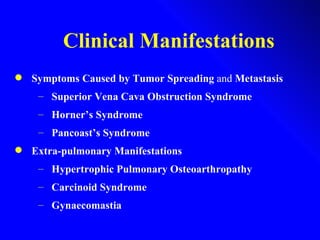

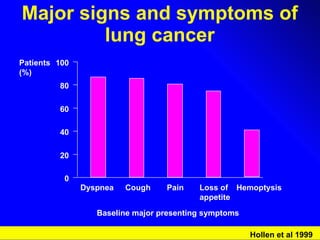

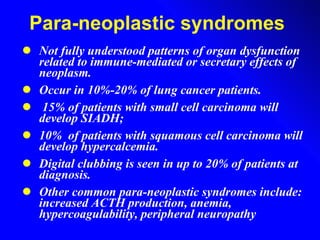

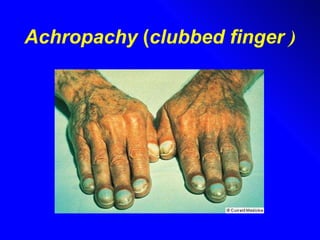

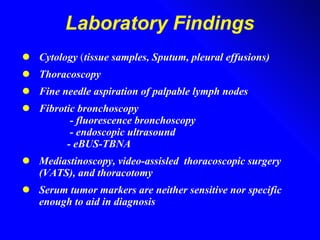

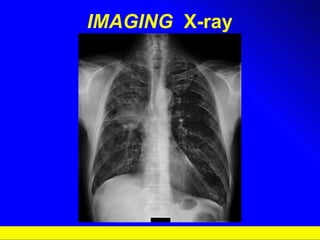

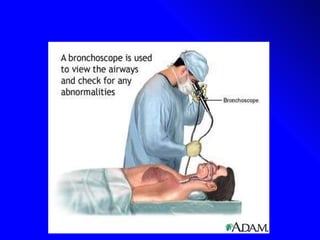

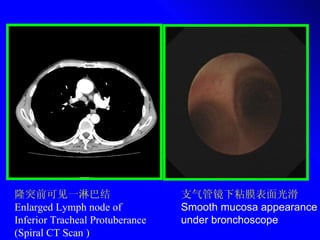

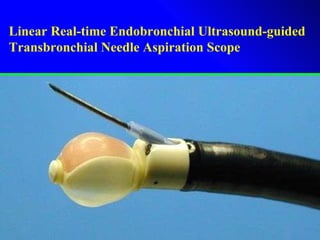

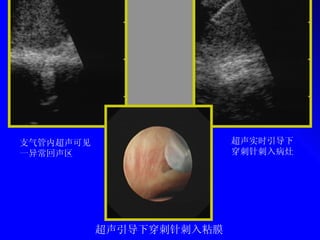

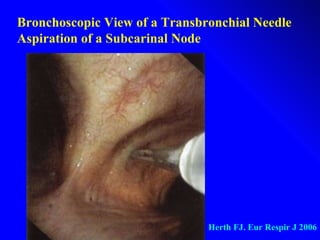

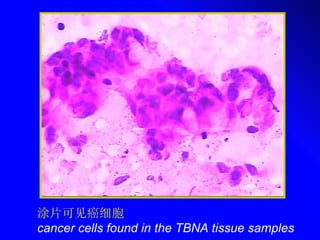

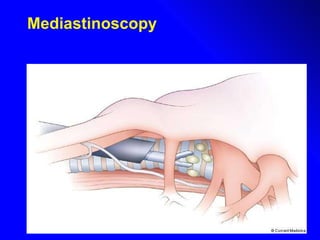

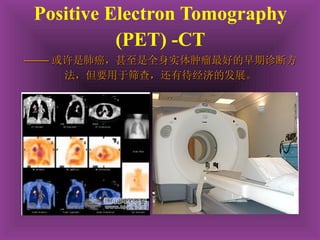

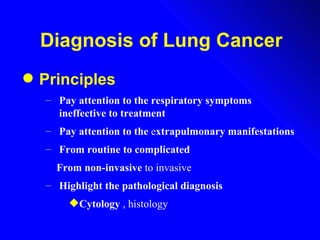

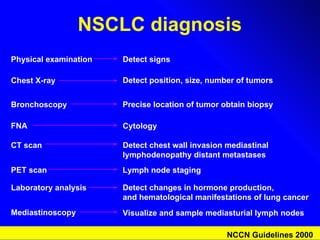

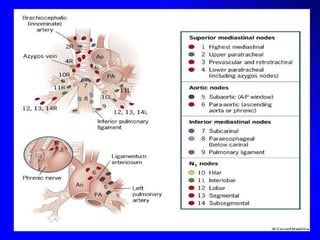

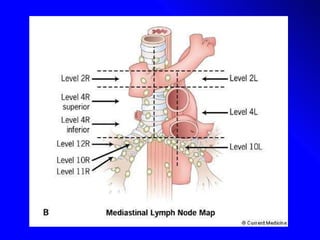

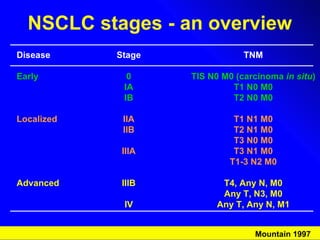

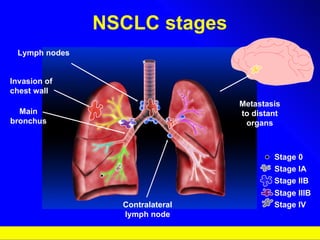

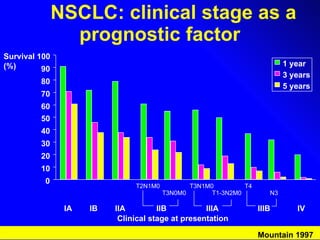

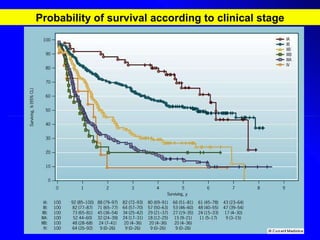

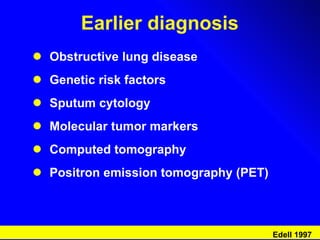

2. It describes the clinical manifestations and symptoms of lung cancer including cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea, as well as diagnostic tests and staging.

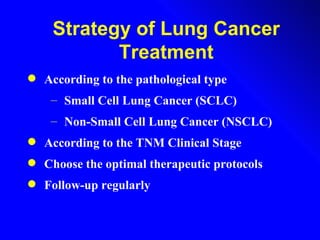

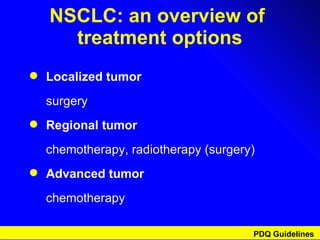

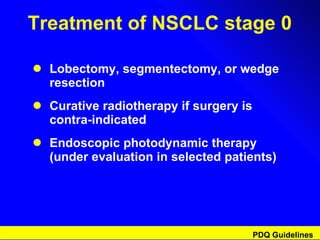

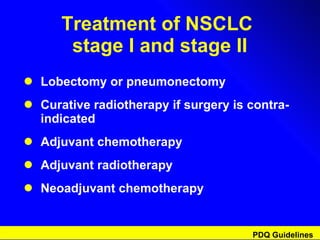

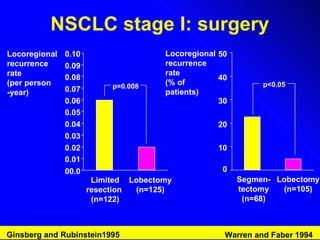

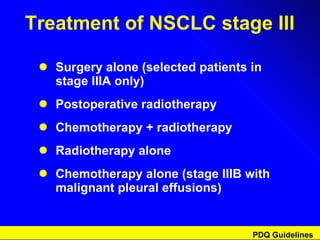

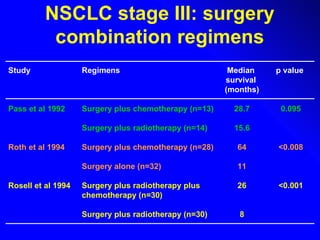

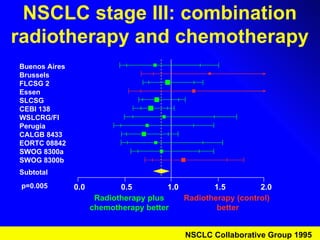

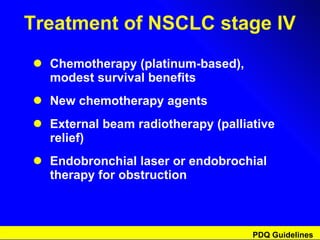

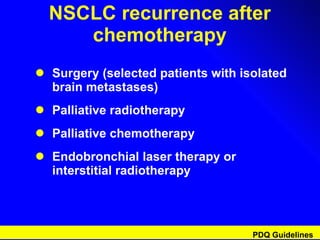

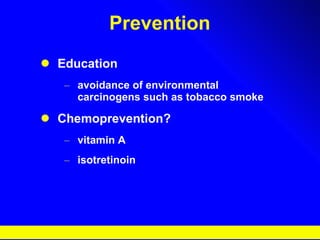

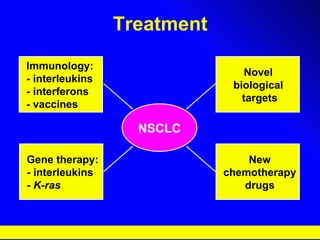

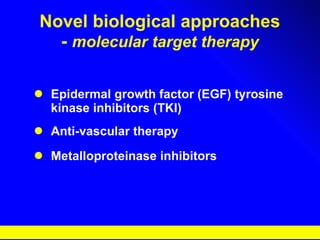

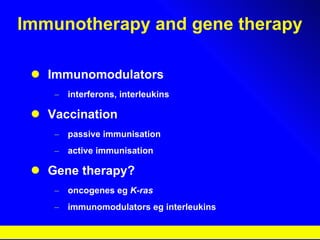

3. It outlines current treatment options for lung cancer such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy depending on the cancer type and stage. Future developments discussed include prevention, earlier diagnosis, and novel biological and immunotherapy approaches.