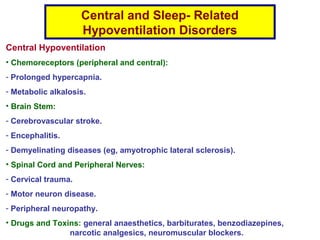

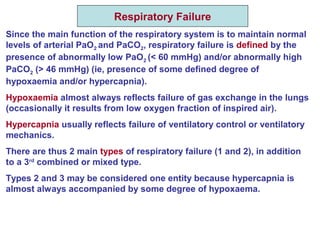

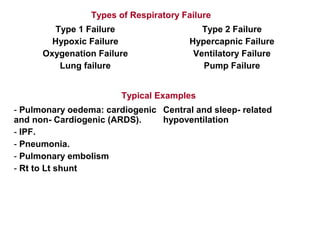

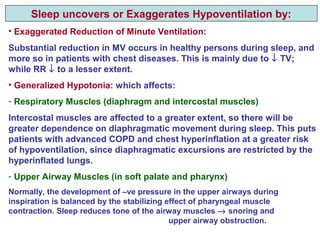

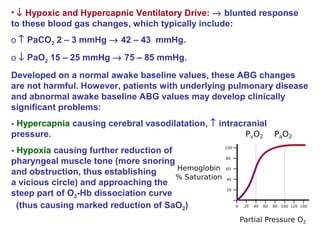

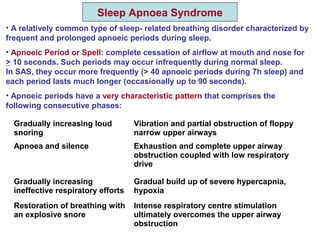

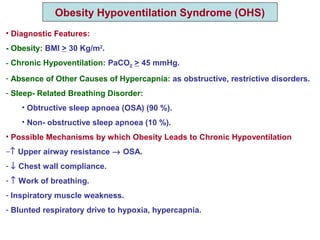

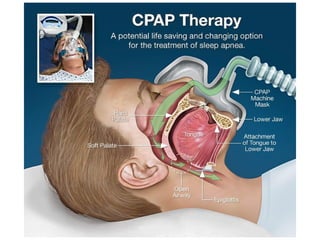

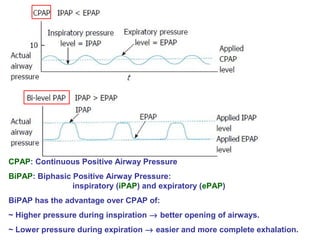

Central and sleep-related hypoventilation disorders involve reduced ventilation that is often only present or worsened during sleep. Central hypoventilation is caused by issues in the brainstem or spinal cord and affects control of breathing. Sleep-related hypoventilation includes conditions like sleep apnea syndrome where breathing stops periodically during sleep. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome involves obesity, sleep disturbances, and chronic hypoventilation. Diagnosis involves blood gas tests showing high carbon dioxide levels, especially during sleep. Treatments include weight loss, breathing exercises, positive airway pressure, and sometimes mechanical ventilation.