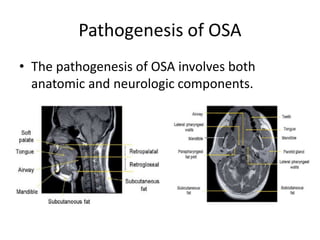

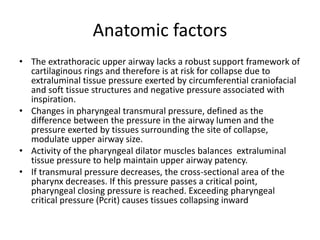

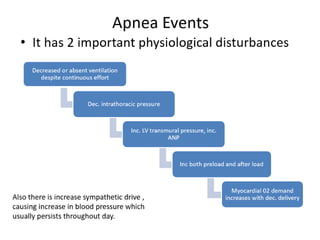

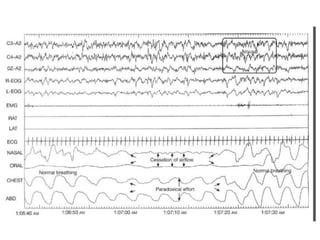

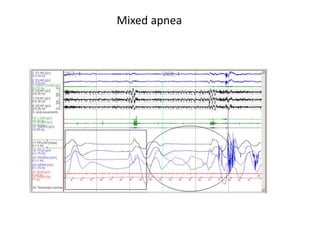

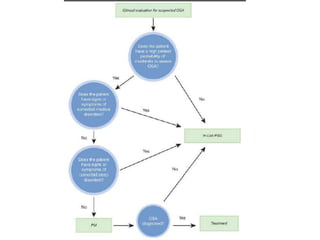

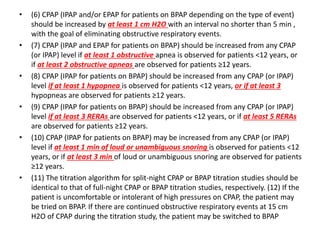

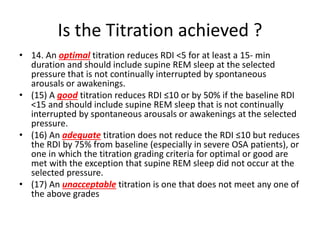

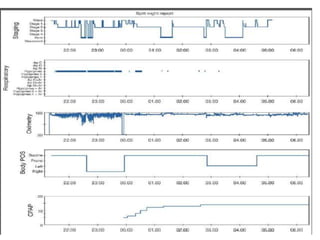

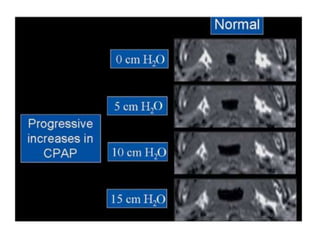

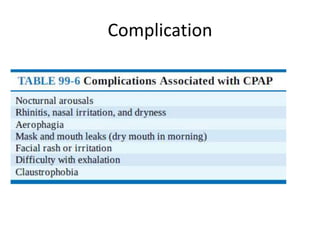

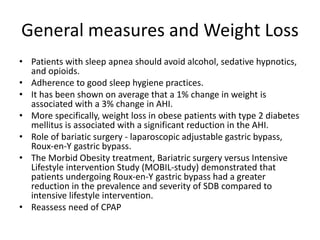

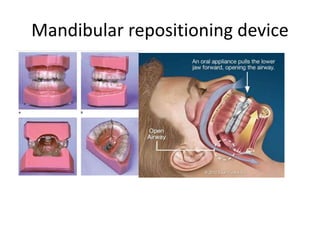

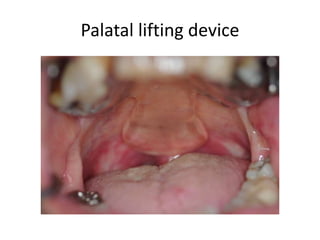

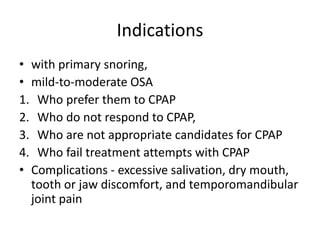

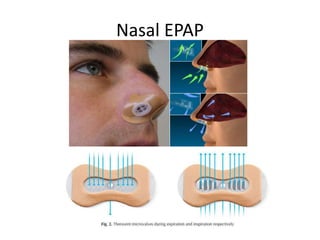

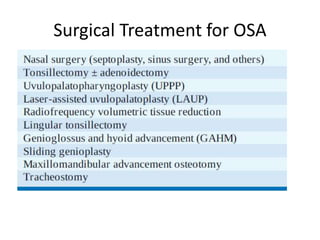

This document provides an overview of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). It discusses the history and definitions of OSA, pathogenesis involving anatomic and neural factors, epidemiology and risk factors such as obesity, and clinical features. The diagnosis of OSA involves screening, nocturnal oximetry, and polysomnography which is the gold standard test. Consequences of untreated OSA include neurocognitive, cardiovascular, and metabolic effects. Treatment options include positive airway pressure therapy, weight loss, oral appliances, surgery, and oxygen. Positive airway pressure therapy with CPAP is the standard treatment and involves titration to determine the optimal pressure level.