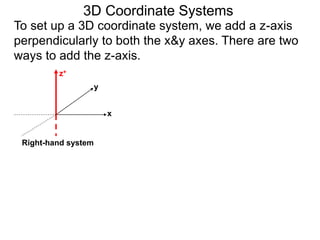

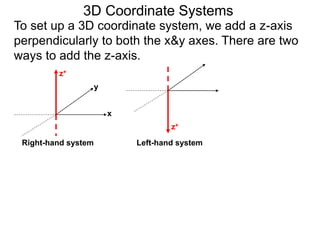

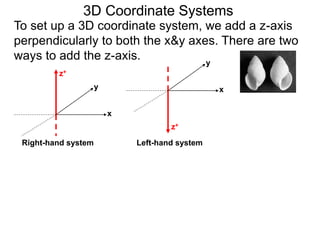

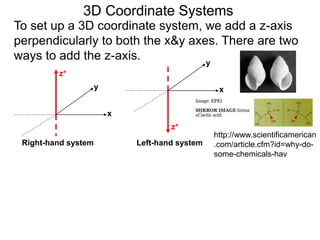

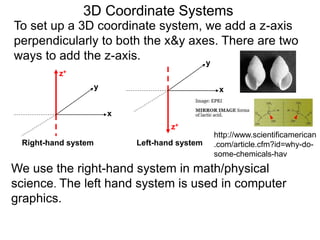

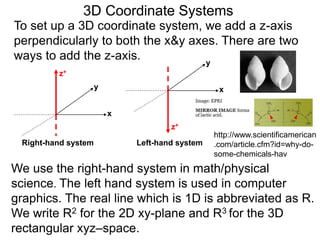

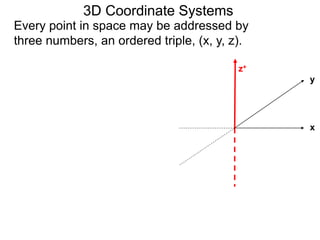

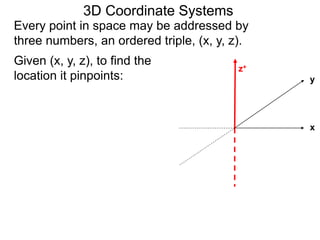

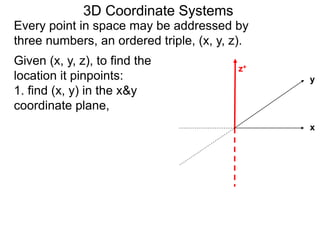

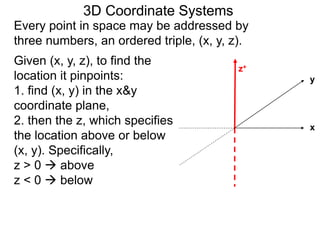

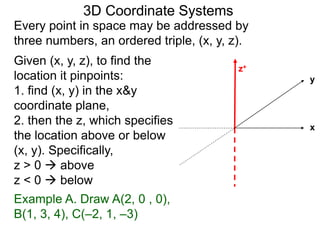

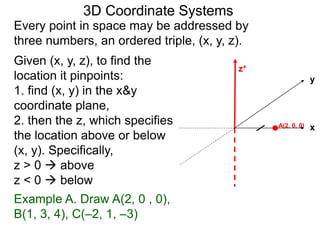

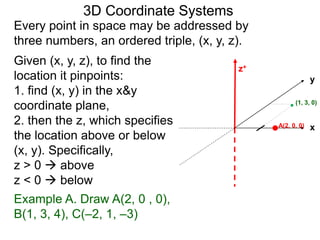

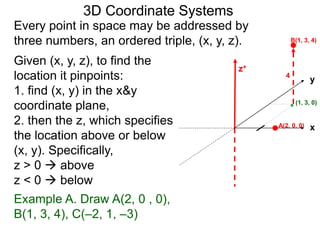

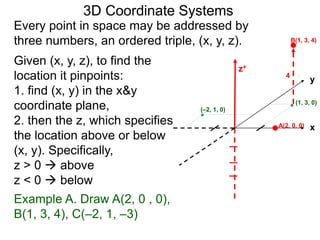

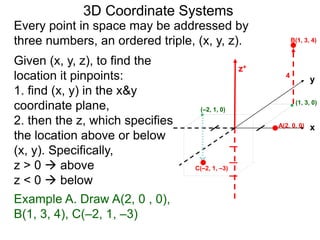

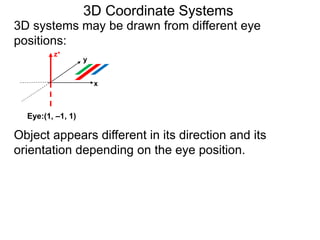

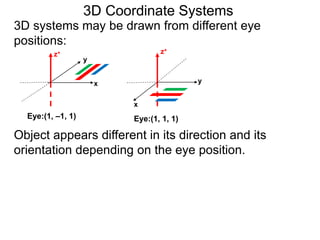

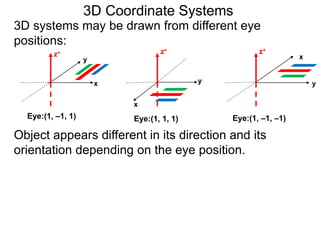

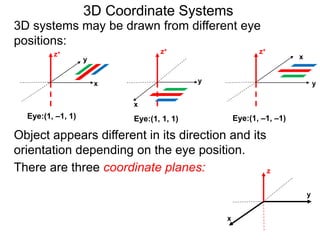

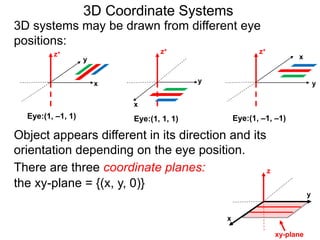

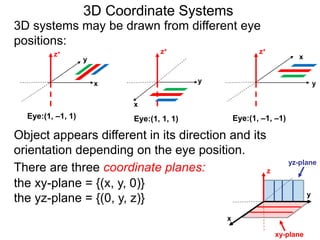

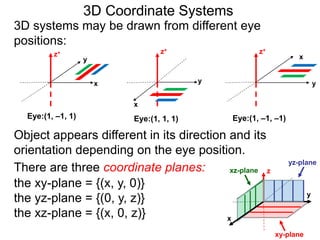

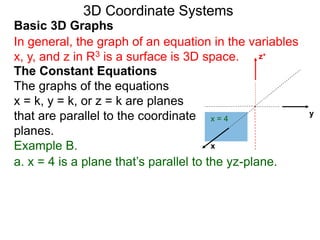

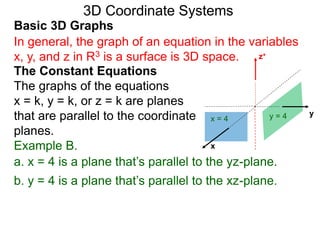

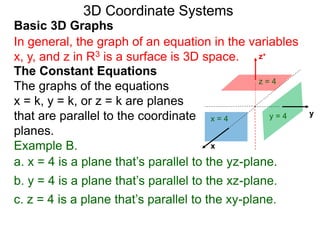

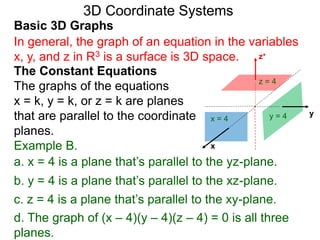

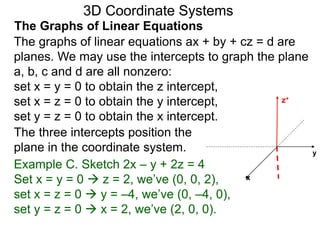

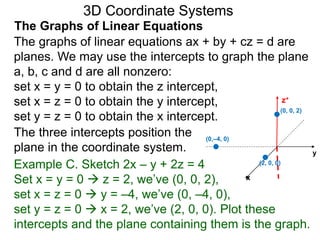

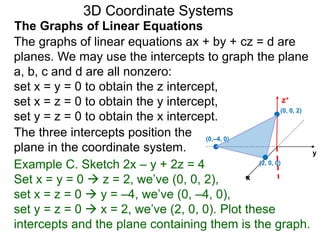

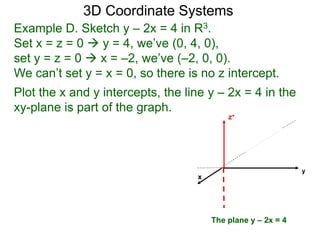

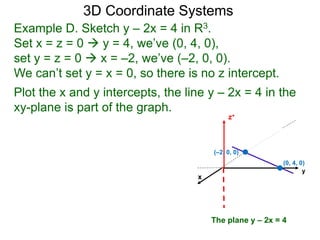

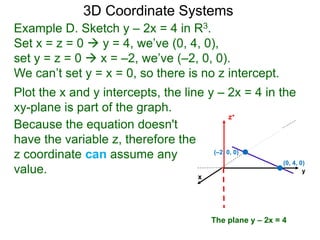

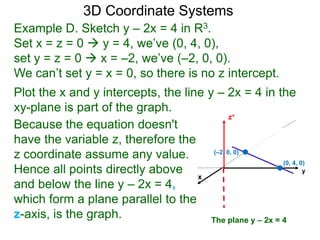

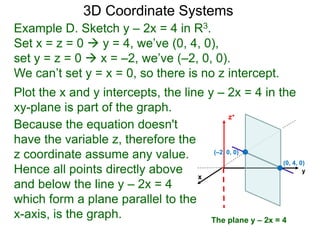

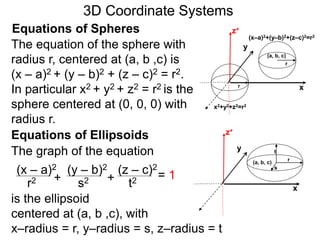

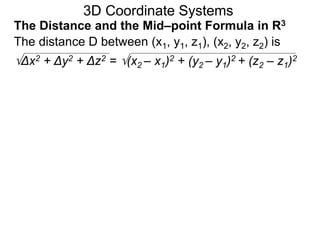

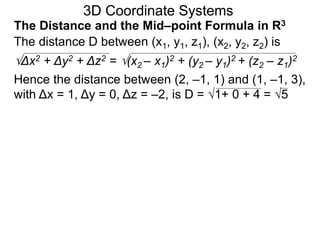

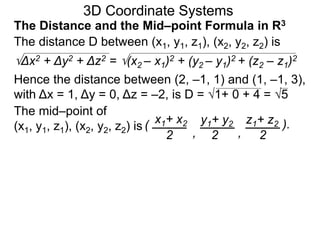

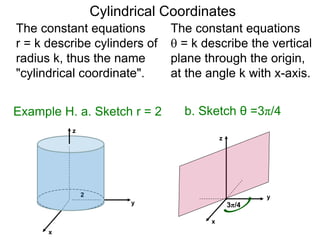

The document discusses 3D coordinate systems. It explains that a 3D coordinate system adds a z-axis perpendicular to the x- and y-axes. There are two ways to orient the z-axis, resulting in right-hand and left-hand systems. Points in 3D space are identified by ordered triples (x,y,z). Graphs of equations in 3D are surfaces. Constant equations like x=k form planes parallel to coordinate planes.