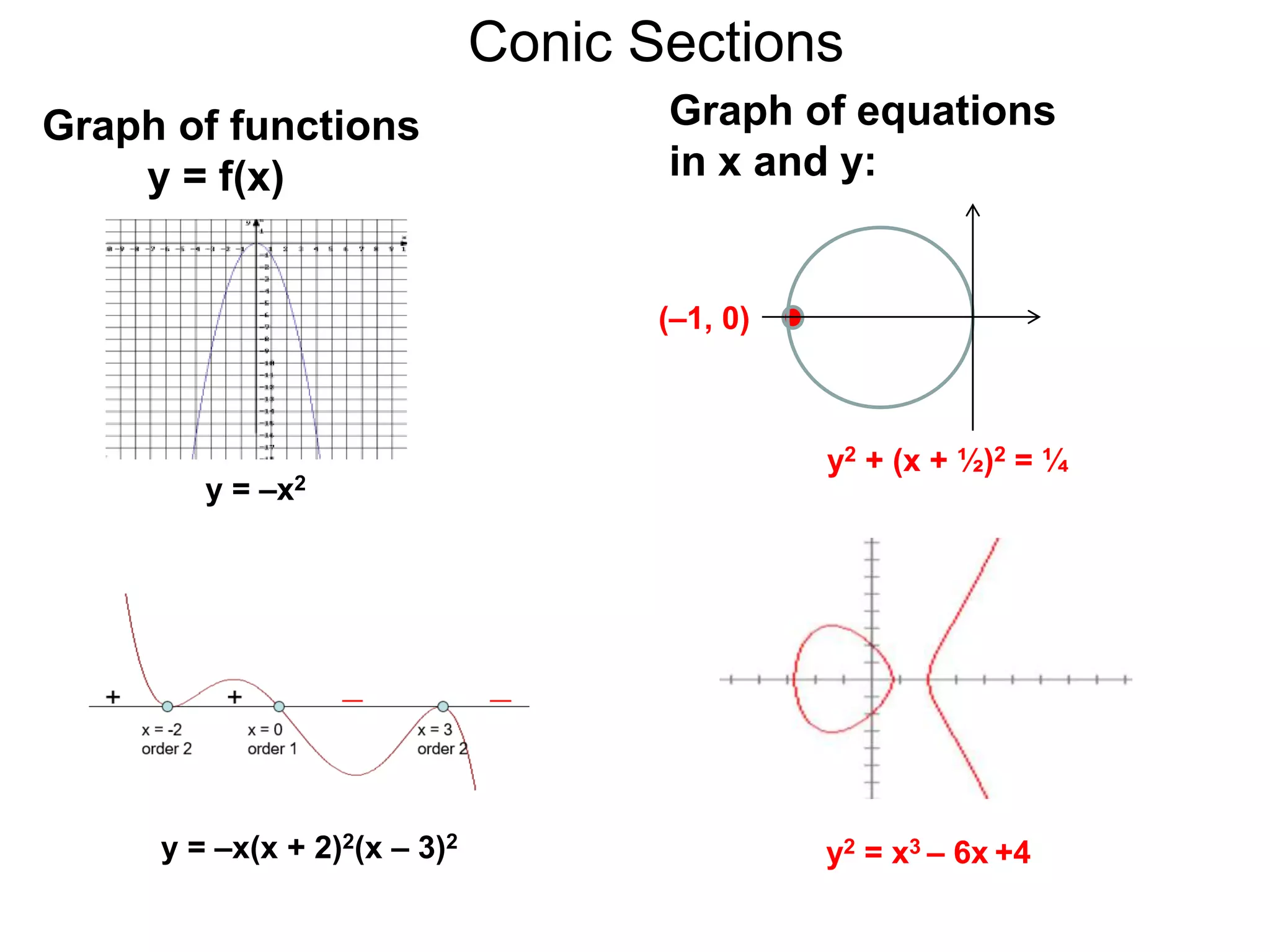

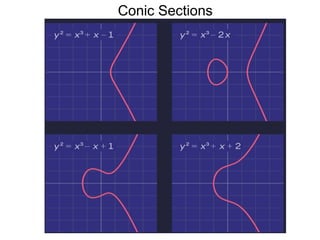

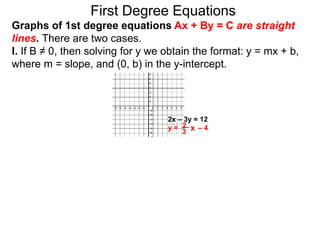

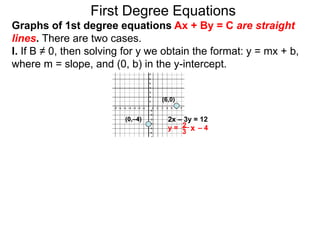

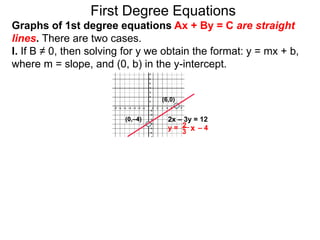

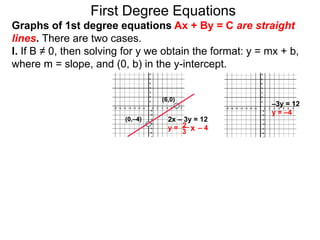

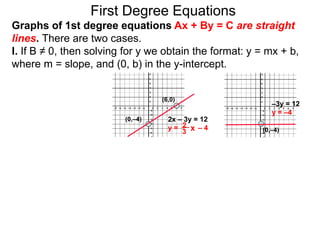

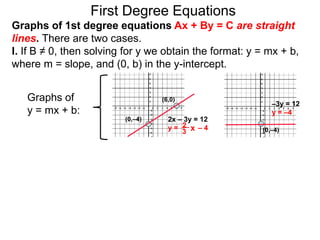

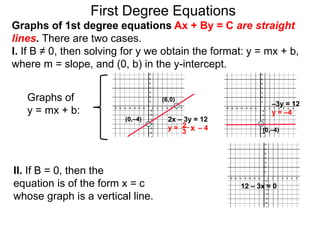

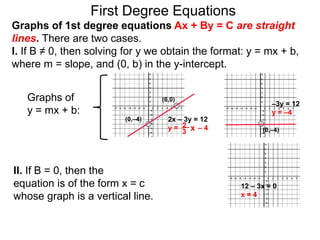

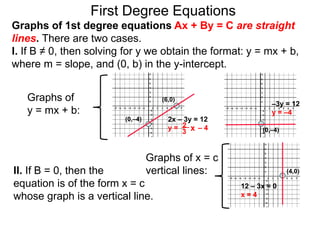

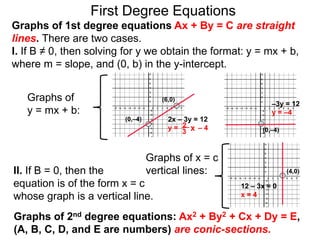

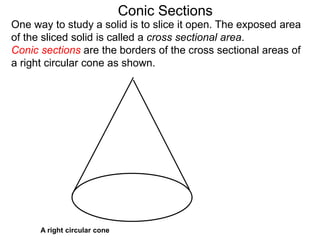

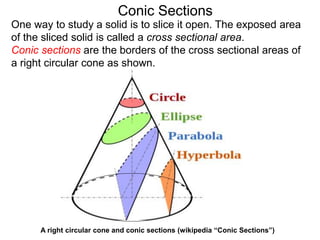

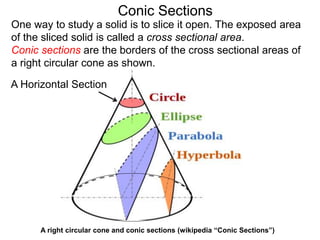

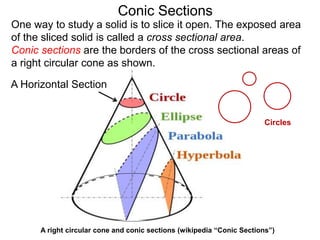

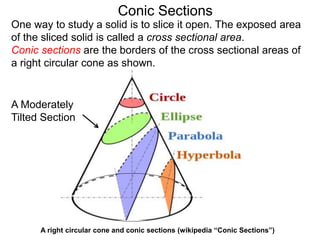

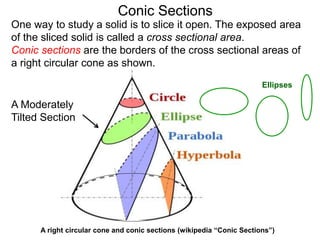

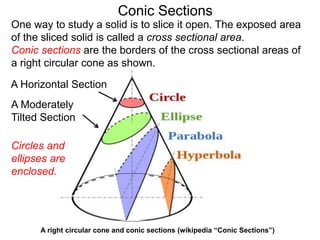

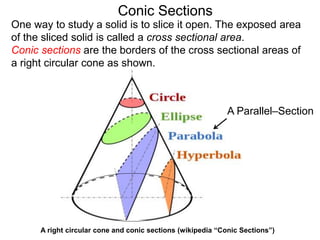

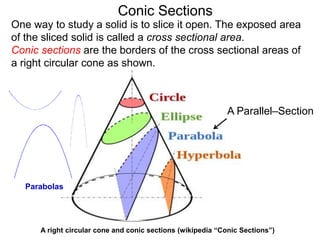

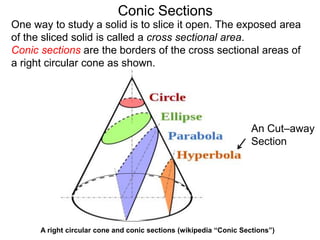

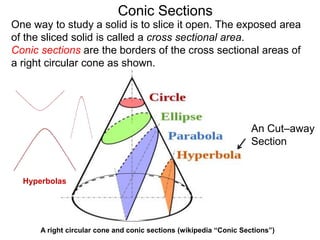

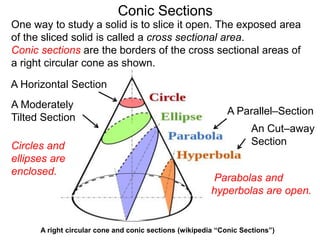

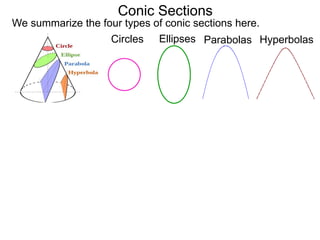

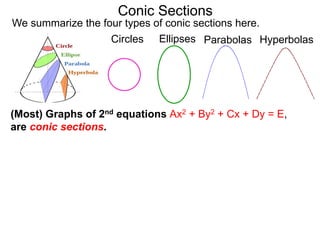

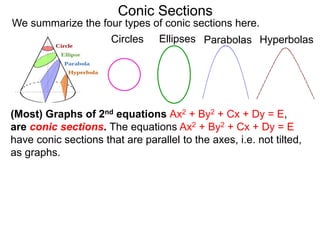

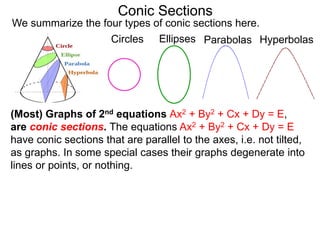

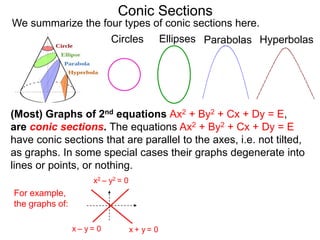

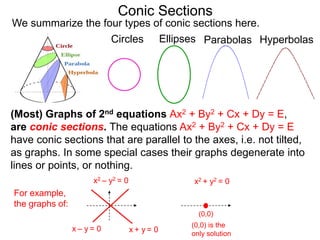

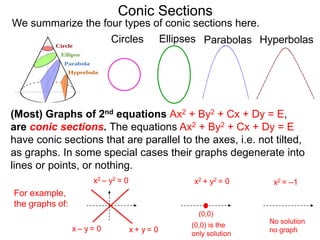

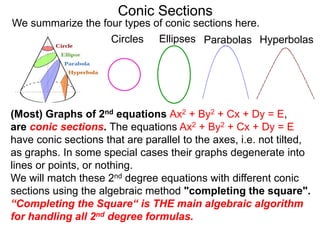

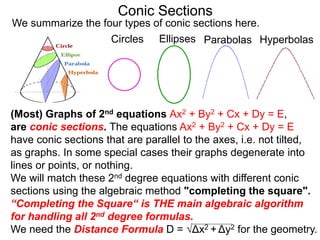

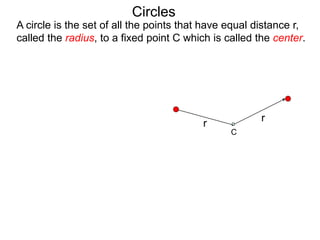

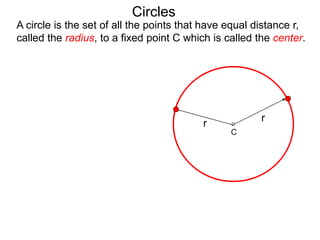

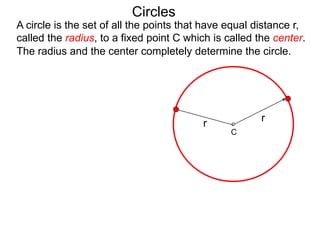

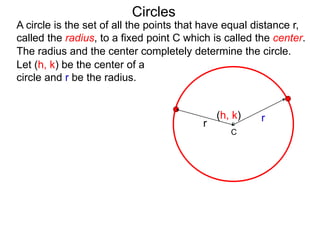

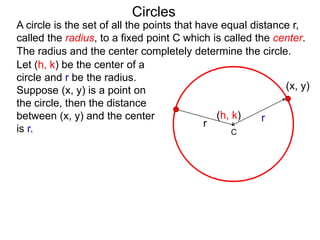

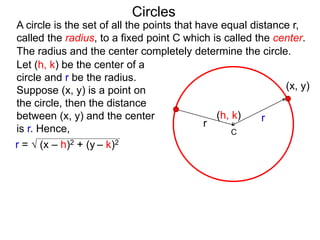

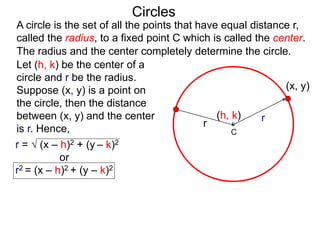

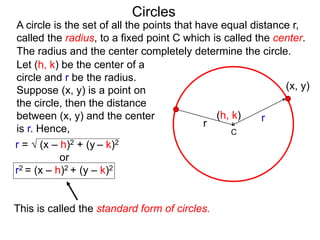

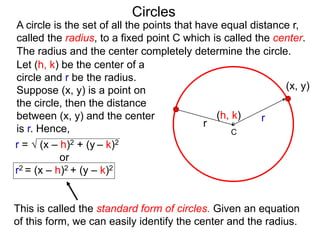

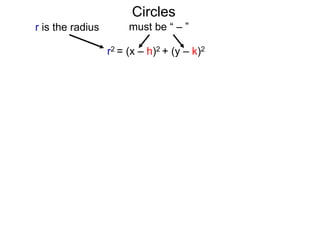

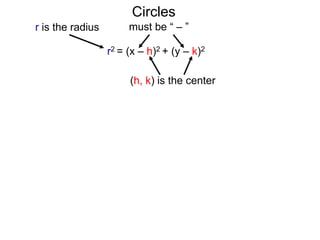

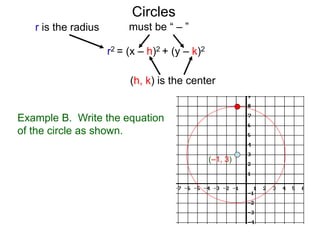

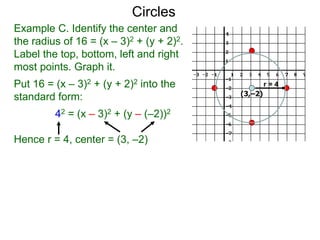

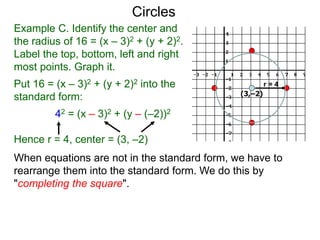

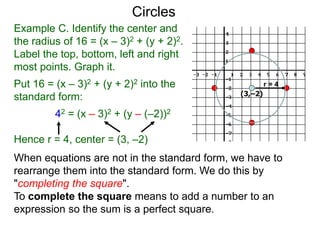

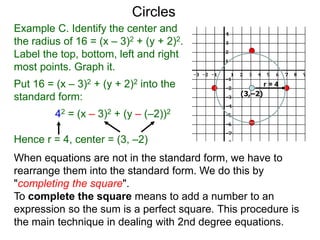

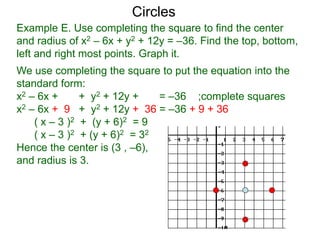

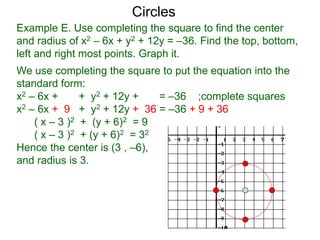

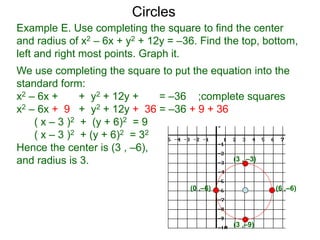

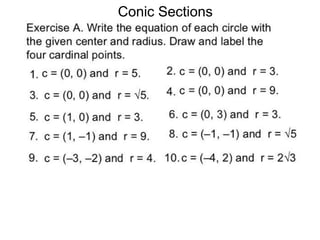

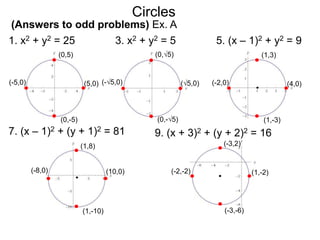

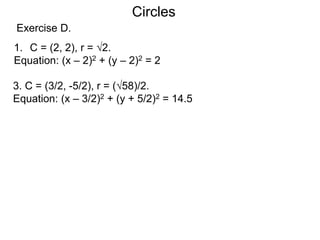

This document discusses conic sections and first degree equations. It begins by introducing conic sections as the shapes formed by slicing a cone at different angles. It then covers first degree equations, noting that their graphs are straight lines that can be written in the form of y=mx+b. Specific examples of first degree equations and their graphs are shown. The document ends by introducing the four types of conic sections - circles, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas - and how graphs of second degree equations can represent these shapes.