1. A second order tensor T is defined as a linear mapping from a vector space V to itself, such that for any vector u in V, there exists a vector w in V where T(u) = w.

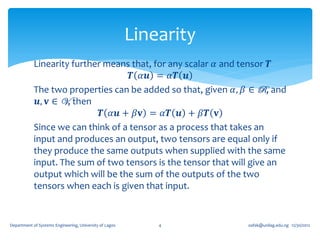

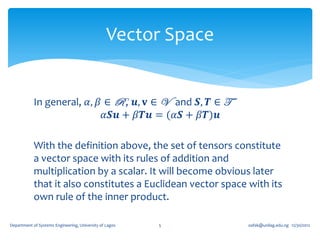

2. Tensors exhibit linearity properties - the mapping is linear, so that T(u + v) = T(u) + T(v) and T(αu) = αT(u) for any scalar α.

3. Special tensors include the zero tensor (which maps all vectors to the zero vector), the identity tensor (which leaves all vectors unaltered), and the inverse of a tensor T (which undoes the mapping of T).

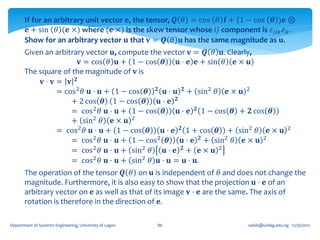

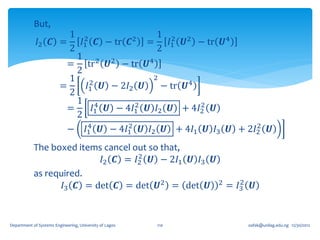

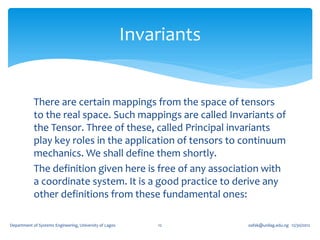

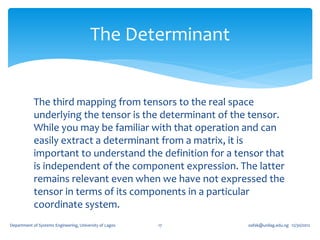

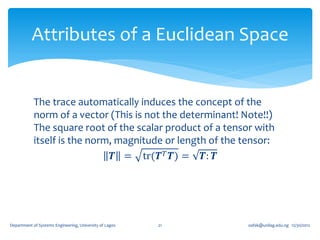

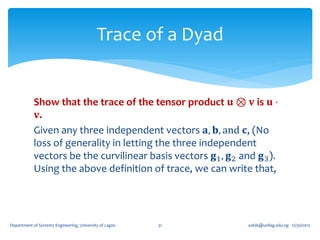

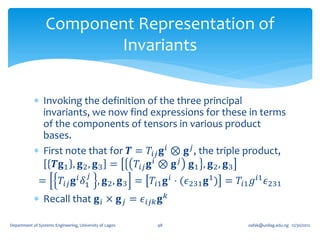

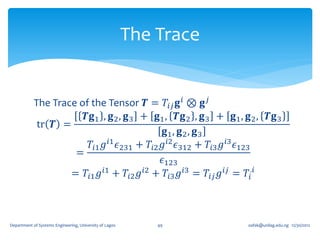

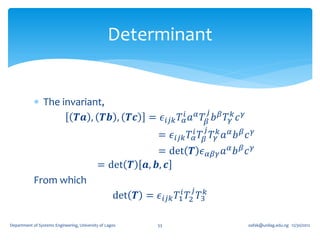

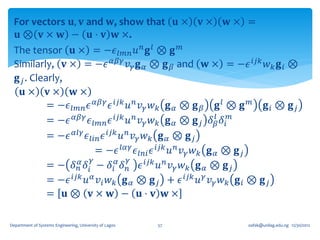

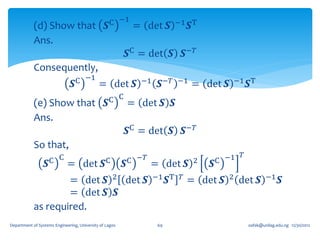

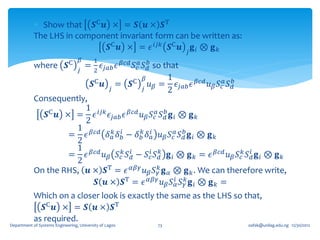

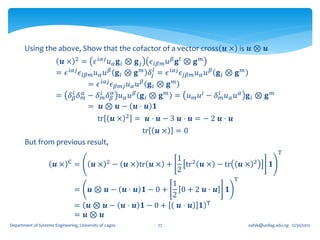

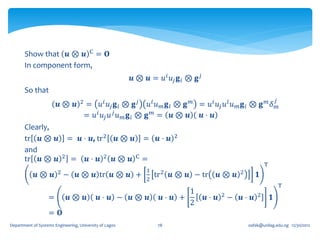

![The Trace

If we write

𝐚, 𝐛, 𝐜 ≡ 𝐚 ⋅ 𝐛 × 𝐜

where 𝐚, 𝐛, and 𝐜 are arbitrary vectors.

For any second order tensor 𝑻, and linearly

independent 𝐚, 𝐛, and 𝐜, the linear mapping 𝐼1 : T → R

𝑻𝐚, 𝐛, 𝐜 + 𝐚, 𝑻𝐛, 𝐜 + [𝐚, 𝐛, 𝑻𝐜]

𝐼1 𝑻 ≡ tr 𝑻 =

[𝐚, 𝐛, 𝐜]

Is independent of the choice of the basis vectors 𝐚, 𝐛,

and 𝐜. It is called the First Principal Invariant of 𝑻 or

Trace of 𝑻 ≡ tr 𝑻 ≡ 𝐼1 (𝑻)

Department of Systems Engineering, University of Lagos 13 oafak@unilag.edu.ng 12/30/2012](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-tensoralgebrajan2013-130103003642-phpapp01/85/2-tensor-algebra-jan-2013-13-320.jpg)

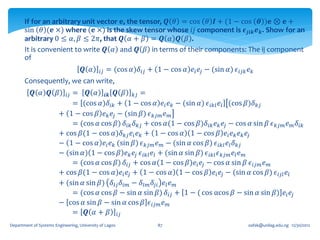

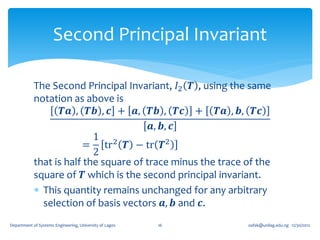

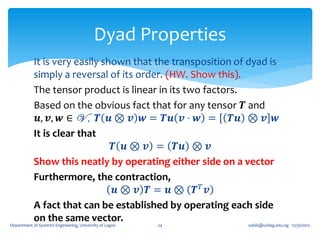

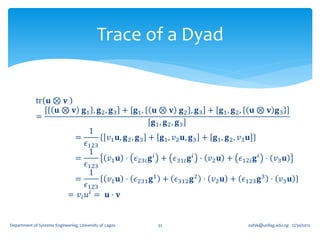

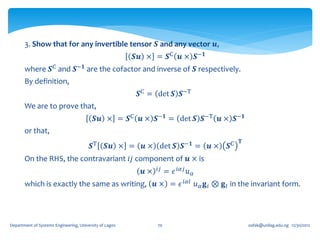

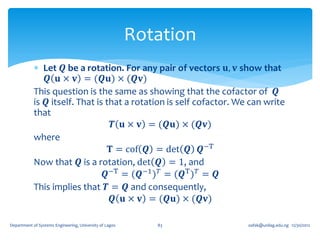

![If for an arbitrary unit vector 𝐞, the tensor, 𝑸 𝜃 = cos 𝜃 𝑰 + (1 − cos 𝜽 )𝐞 ⊗

𝐞 + sin 𝜃 (𝐞 ×) where (𝐞 ×) is the skew tensor whose 𝑖𝑗 component is 𝝐 𝒋𝒊𝒌 𝒆 𝒌 ,

show that 𝑸 𝜃 (𝑰 − 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞) = cos 𝜃 (𝑰 − 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞) + sin 𝜃 (𝐞 ×).

𝑸 𝜃 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 = cos 𝜃 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 + (1 − cos 𝜽 )𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 + sin 𝜃 [𝐞 × 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 ]

The last term vanishes immediately on account of the fact that 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 is a

symmetric tensor. We therefore have,

𝑸 𝜃 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 = cos 𝜃 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 + (1 − cos 𝜽 )𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 = 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞

which again mean that 𝑸 𝜃 so that

𝑸 𝜃 𝑰 − 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 = cos 𝜃 𝑰 + 1 − cos 𝜽 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 + sin 𝜃 𝐞× − 𝐞⊗ 𝐞

= 𝑐os 𝜃 𝑰 − 𝐞 ⊗ 𝐞 + sin 𝜃 𝐞 ×

as required.

Department of Systems Engineering, University of Lagos 85 oafak@unilag.edu.ng 12/30/2012](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2-tensoralgebrajan2013-130103003642-phpapp01/85/2-tensor-algebra-jan-2013-85-320.jpg)